A white president speaks at historically black colleges...

William McKinley's many messages to African American students

In the early 20th century, it become commonplace for U.S. presidents to address students on university campuses, particularly at commencements. Since 1902, according to the American Presidency Project database at the University of California-Santa Barbara, our chief executives—from Theodore Roosevelt to Joe Biden—have delivered at least 172 commencement addresses, out of thousands of speeches and remarks whose content is recorded there.

But the database is still a work in progress, and does not include all presidential speeches delivered on college campuses, whether at commencements or other occasions, either before 1902 or since. Remarks delivered by President William McKinley in such settings between 1897 and 1901, for instance, were not not, strictly speaking, “commencement” addresses, or even important policy statements, but were shorter speeches addressed to the specific student bodies at schools in states he happened to be visiting.

McKinley spoke, for instance, at four historically black institutions of higher learning (HBCUs)—all of which still exist today—on two Southern trips in 1898 and 1901. They included the campuses of Savannah State University in Georgia and Tuskegee University in Alabama in December 1898, and the campuses of Southern University in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Prairie View A & M University in Texas, during his final cross-country tour in May 1901, two months after his second inauguration.

McKinley was not the first president to visit an HBCU—Rutherford B. Hayes had visited Hampton Institute (now University) in 1880. But he did so more frequently—four times in three years— than any of his successors until Bill Clinton, who gave commencement addresses at four HBCUs during two terms in office in the 1990s: Grambling State, Morgan State, Philander Smith, and Allen University.

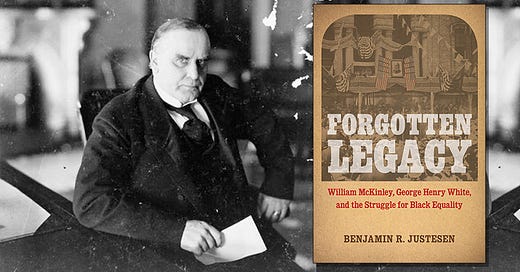

In my 2020 book, Forgotten Legacy: William McKinley, George Henry White, and the Struggle for Black Equality (LSU Press), I wrote at some length about McKinley’s four speeches because his messages of encouragement to black students underscored his demonstrated commitment to advancing the opportunities open to the nation’s African Americans—a legacy for which he has traditionally received little credit. In addition to appointing more blacks to federal government office than all of his predecessors combined—and indeed, more than any succeeding president until Franklin D. Roosevelt—McKinley met regularly with the nation’s black leaders to listen to their advice and views on issues of the day.

President William McKinley and his enduring message of encouragement to African Americans.

Photo courtesy LSU Press.

But he did not give commencement addresses, preferring to select his venues at other times of year with a more personal touch. His successor, Theodore Roosevelt, would begin that tradition in 1902. And unlike at least six of his successors—Calvin Coolidge (1924), Herbert Hoover (1932), Franklin Roosevelt (1936), Harry Truman (1952), Lyndon Johnson (1965), and Barack Obama (2016)—McKinley chose not to speak at the geographically most convenient HBCU: Washington’s Howard University, located just blocks from the White House.

Perhaps he wished to avoid having his remarks unduly politicized, for what he said was almost always personal, and dealt with the importance of education, not the substance of major policy statements, such as the significant civil rights address delivered at Howard by Lyndon Johnson in 1965. Yet his remarks at the four schools clearly resembled commencement addresses—along with those at other sites, including one of Chicago’s largest black congregations in 1899 (Quinn Chapel AME Church). His words regularly bespoke his clear and lifelong commitment to opportunity and fair treatment for the nation’s black citizens, as well as praising their demonstrated reputation for military valor.

In mid-December 1898, having traveled by train after delivering speeches to the Georgia and Alabama legislatures, President McKinley spoke to a breakfast at Alabama’s Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, the well-known private school run by Booker T. Washington, a black educator and leader McKinley had recently come to know and appreciate.

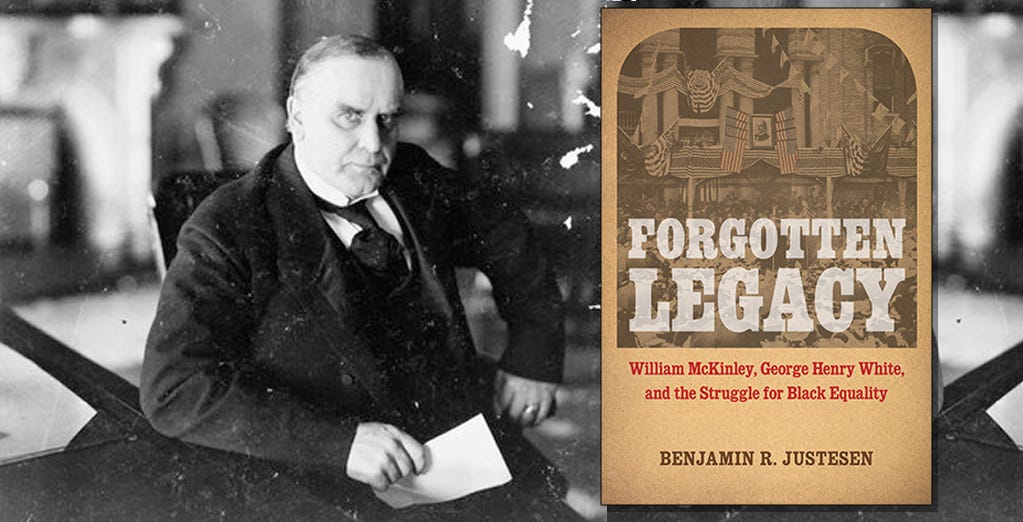

President William McKinley (top row, second from left) with Booker T. Washington

at Tuskegee, Alabama, December 1898. Library of Congress photo.

McKinley praised Washington’s “worthy reputation as one of the great leaders of his race, widely known and much respected at home and abroad,” and spoke warmly of the “unique educational experiment, which has attracted the attention and won the support even of conservative philanthropists in all sections of the country.” Like Virginia’s Hampton Institute—Washington’s alma mater, at which President Rutherford B. Hayes had spoken in 1880, and the school on which Tuskegee was clearly modeled— “is to-day of inestimable value in sowing the seeds of good citizenship. Institutions of their standing and worthy patronage form a steadier and more powerful agency for the good of all concerned than any other yet proposed or suggested.”

Pointedly addressing the assembled African American students, McKinley declared that, ”The practical here is associated with the academic, which encourages both learning and industry. Here you learn to master yourselves, find the best adaptation of your faculties, with advantages for advanced learning to meet the high duties of life. No country, epoch, or race has a monopoly upon knowledge. Some have easier, but not necessarily better, opportunities for self-development. What a few can obtain free, most have to pay for, perhaps by hard physical labor, mental struggle, and self-denial.”

The Tuskegee model offered a rare opportunity, the President said, to better themselves— “provided they exercise intelligence and perseverance, and their

motives and conduct are worthy. Nowhere are such facilities for universal education

found as in the United States … accessible to every boy and girl, white or black.”

Then, almost as if delivering a sermon to his fellow Methodists, McKinley singled out “integrity and industry,” which was available through such education as offered by Tuskegee, as “the best possessions which any man can have, and every man can have them … They are a good thing to have and keep. Every avenue of human endeavor

welcomes the … only keys to open with certainty the door of opportunity to struggling manhood. Employment waits on them; capital requires them; citizenship is not good

without them. If you do not already have them, get them.”

McKinley clearly relished his newfound role as academic cheerleader-in-chief, repeating much the same message two days later at the Georgia Agricultural and Mechanical College in Savannah [now Savannah State]. This time, he added a more timely reference to the recent war with Spain—and the debt owed by the nation to its black volunteer soldiers, including his personal friend, school president Richard R. Wright Sr., whom he had appointed earlier that year as the Army’s first black wartime paymaster.

Meldrim Hall, on Savannah State campus, where President McKinley spoke in December 1898, as it looked in 1953 (later demolished). Photo courtesy Asa H. Gordon Library Special Collections

“Keep on, is the word I would leave with you to-day. Keep on in the efforts upward, but remember that in acquiring knowledge there is one thing equally important , and that is character. Nothing in the whole wide world is worth so much, will last so long, and serve its possessor so well as good character. It is something that no one can take from you, that no one can give to you. You must acquire it for yourself.”

“I congratulate you upon the valor of your race. … At San Juan hill and at El Caney -- but General [Joseph] Wheeler is here … [and] he can tell you better than I can of the heroism of the black regiments which fought side by side with the white troops on those historic fields. Mr. Lincoln was right when, speaking of the black men, he said that the time might come when they would help to preserve and extend freedom. And in a third of a century you have been among those who have given liberty in Cuba to an oppressed people.”

In closing, the President spurred his audience to “Keep on. You will solve your own problem. Be patient, be progressive, be determined, be honest, be God-fearing , and you will win, for no effort fails that has a stout, honest, earnest heart behind it.”

* * * * * *

The President’s second Southern swing took place in May 1901, after his reelection and second inauguration. The cross-country train trip was planned as the longest ever taken by a sitting Presidents, and included stops in Tennessee, Louisiana, Texas, and California, before returning along the nation’s northern border with Canada—although it was cut short by the nearly-fatal illness suffered by Mrs. McKinley, who was rushed back to Washington from San Francisco.

McKinley became the first sitting president to visit New Orleans, where he addressed a crowd of some 5,000 residents gathered outside the Magazine Street campus of Southern University—the city’s only public college for blacks, with three other historically-black private schools at the time—with warm words of encouragement to his cheering audience.

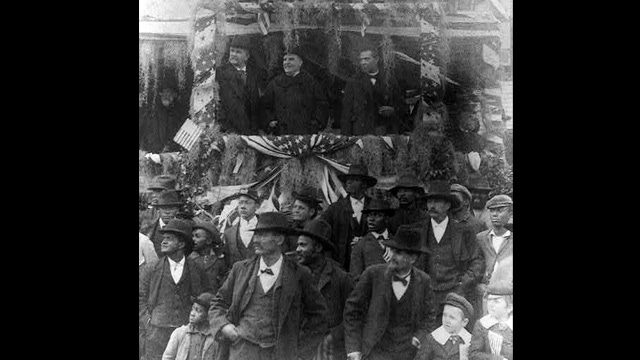

President McKinley at Southern University in New Orleans, May 1901.

(John Norris Teunisson Photograph Collection, Louisiana State Museum)

The Washington Evening Star captured the chief executive’s intentions in its article chronicling the visit: “The President desired to honor the colored people while here, and so he visited Southern University, where he was received with hearty demonstrations of good will by the colored officials, students, and people. He was touched by these evidences of the profound respect in which he is held by the negro race” (“Seeing New Orleans,” Evening Star , May 3, 1901).

The President’s campaigning days were now long behind him; he spoke to the African American crowd as if they were simply his friends, offering earnest advice rather than lofty political language. McKinley’s speech was brief but effusive: “I am glad to know that all over the South, where most of you dwell, the state has provided institutions of learning where every boy and girl can prepare themselves for usefulness and honor under the government in which they live,” he said, before leaving on a tour with the state’s governor and city’s mayor.

“The thing today is to be practical. What you want is to get education, and with it you want good character, and with these you want unfaltering industry, and if you have these three things, you will have success anywhere and everywhere. God bless you.”

For the record: Southern University continued to operate at this location until 1914, when the state campus moved to Scotlandville, Louisiana, near Baton Rouge. There it became the flagship—Southern University and A&M College—of the five-school Southern University system. (That system’s newer, separate New Orleans campus, opened in 1959, is an offspring. The Magazine Street building itself was sold to Katharine Drexel, the prominent Catholic educator, as the first site of Xavier University of Louisiana; today it houses St. Katharine Drexel Preparatory School, not affiliated with Xavier.)

McKinley’s next stop was part of his grand tour of Texas, covering the cities of Houston, Austin, and El Paso, as well as the small town of Prairie View, home to Prairie View State Normal and Industrial College (now Prairie View A&M). Originally established (1876) by the Texas Constitution, on the site of a former slave plantation, as “Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas for Colored Youths,” it occupied a small town about 50 miles northwest of Houston, the second-largest Texas city in 1900.

The Prairie View visit had been urged for the White House by Judson Lyons, the black Register of the U. S. Treasury, one of the four highest offices traditionally accorded African Americans—and a close political adviser of McKinley. Lyons was a colleague of the Prairie View principal, a rising Texas educator named Edward L. Blackshear (1862-1919), and the head of Texas’s only public college for black students.

McKinley’s message to his audience at the small school, probably delivered from the doorway of his railroad car during a brief stopover, was nearly identical to the Savannah address of 1898. As quoted days later in the Washington Bee, he noted first his “great satisfaction to observe the advancement of your race since the immortal proclamation of liberty was made. The opportunity for learning is a great privilege. The possession of learning is an inestimable prize,” offering the opportunity to “enlighten your minds and prepare yourselves for the responsibilities of citizenship under this free Government of ours” (“Defends the Negro,” Washington Bee, May 11, 1901).

Again, McKinley praised the recent valor shown by black soldiers in the Cuban campaign, and then subtly compared the goals of the students before him to those brave soldiers. “What we want more than anything else, whether we be white or we be black—what we want is to know how to do something well. If you will just learn how to do one thing that is useful better than anyone else can do that one thing, you will never be out of a job. … The race is moving on and has a promising future.”

* * * * *

The Prairie View address was fated to be McKinley’s last speech before an audience of black students, though he would give two more major addresses that year—one during the same tour in El Paso, Texas, where he urged an end to old sectional problems and a new future, led by “men of all races, all nationalities, and all creeds … united in their allegiance to their country.” That would be followed by his final major speech, delivered four months later in Buffalo, New York, one day before his assassination.

That speech, offered at the Pan-American Exposition, dealt almost exclusively with the bright and peaceful economic future he saw unfolding for the nation he clearly loved: “our interest is in concord, not conflict … our real eminence rests in the victories of peace, not those of war.” Yet he clearly saw what he hoped would be a future after the nation’s racial differences had been transcended, and all men and women could coexist in prosperity and peace.

McKinley’s death would end—for two decades, at least—the tradition he started of seeking out youthful black audiences for special remarks. Theodore Roosevelt instead would begin a new tradition, delivering two commencement addresses in 1902 at U.S. military academies: the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, and at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, and at other schools later in his terms. Over the next century, every U.S. president would deliver at least one commencement speech during his term—George H. W. Bush holding the record for six in one year, all delivered in 1989.

But after McKinley’s death, presidential visits to HBCUs would not resume until 1909—if without recorded remarks—when President William Howard Taft visited Hampton Institute, ostensibly in his role as chairman of the school’s board of trustees. Taft’s visit was followed by his May 1912 trip to Savannah State, just before he began his unsuccessful reelection campaign.

The resumption of public speeches, however, would take another decade. The next sitting president after McKinley to speak at a historically black college would be President Warren Harding, who delivered the commencement address at Lincoln University in Chester County, Pennsylvania, in June 1921—and then proceeded to shake the hand of every astonished Lincoln graduate that day.

It would be three years later, in June 1924, that his successor, President Calvin Coolidge, became the first of many to give the commencement speech at the nation’s premier HBCU, Howard University, in Washington, D.C.

Next time: An unusual presidential election in 1900, featuring old faces and new ones

As we've discussed, my Arkansas (maternal) grandmother was an ardent believer in the mythology of the Lost Cause. She, like so many others, dismissed efforts like McKinley's as purely political. As she put it, it was just "(Yankee) Republicans catering to (Southern Blacks) for votes."