What do 125 nineteenth-century African American men from North Carolina have in common

With former congressman George Henry White ... and a future chief justice

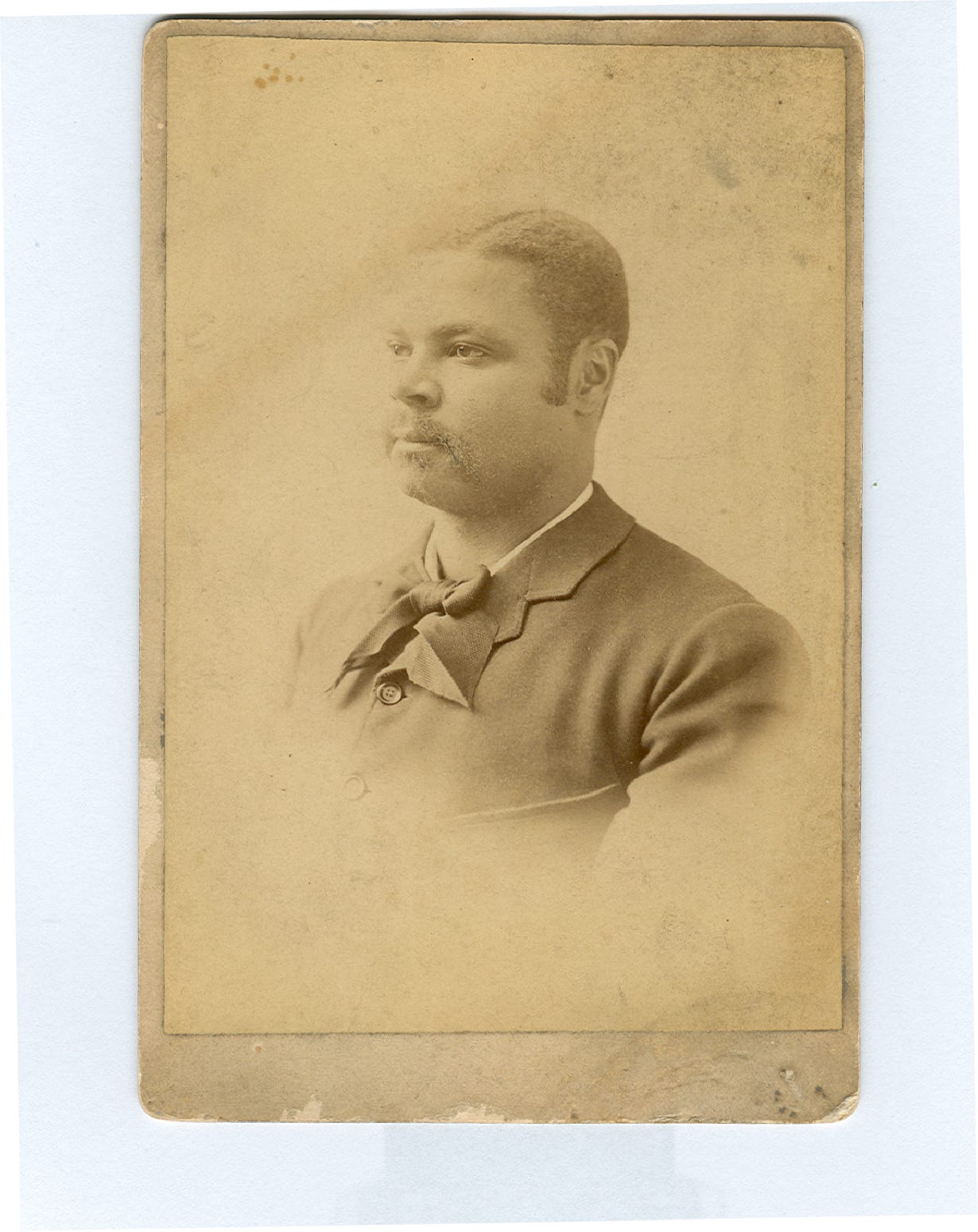

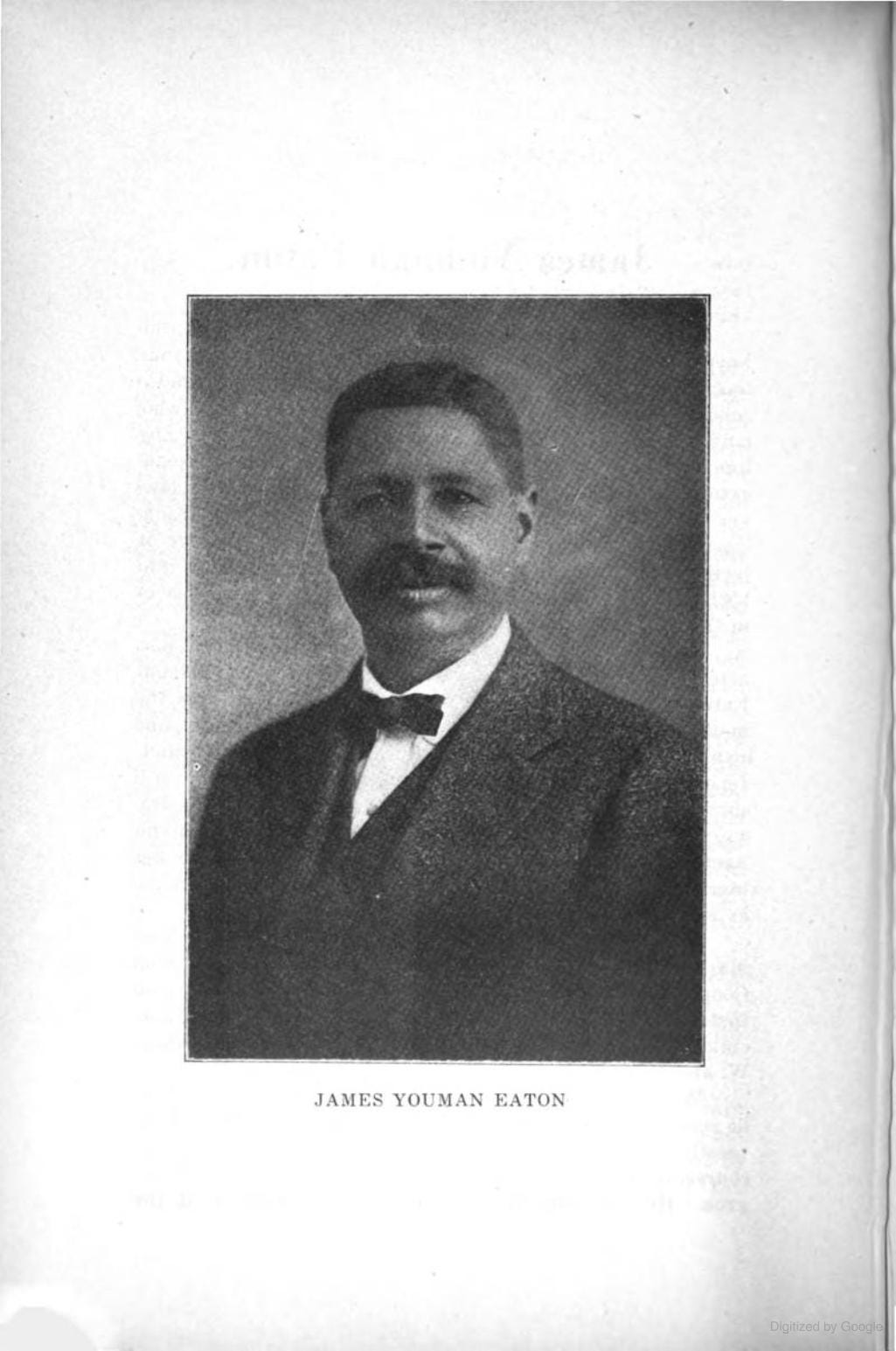

What do Aaron R. Bridgers, James Youman Eaton, John Sinclair Leary, George Lawrence Mabson, and Robert W. Williamson have in common with each other—and George Henry White? If you grew up in North Carolina during the middle of the twentieth century, and were taught the state’s history in public schools—perhaps even in college—you would probably not have learned this answer: they were all trained lawyers, and they all served in the North Carolina General Assembly (NCGA) between 1868 and 1900. And they were all African Americans.

John Sinclair Leary (1845-1904), member of NCGA,

Cumberland County, 1868, 1870

And like their better-known Republican colleague, future Congressman George H. White, a lawyer who represented Craven County in the N.C. House in 1881 and the Eighth District in the N.C. Senate in 1885, their names were largely omitted from the history books. Like almost all of the 128 black Republican legislators elected from predominantly black counties in the eastern portion of the state—most from just 12 of the state’s 99 counties—they are rarely remembered outside their home counties, if then. But slowly, their names are only now being reclaimed from the dustbin of history.

George Henry White (1852-1918), member of NCGA, Craven County, 1881, 1885

Black History Month offers a chance for us to remember their achievements. Only a handful of the 128 identified so far—the state does not keep records by race of those who served—were actually trained lawyers. At least two later became doctors. Many others were college educated, and most of them worked as schoolteachers, ministers, businessmen, or farmers. Some served as many as five terms. They hailed almost exclusively predominantly black counties in the eastern section of the state: Bertie, Caswell, Craven, Edgecombe, Granville, Halifax, New Hanover, Northampton, Pasquotank, Vance, and Warren, and the capital county of Wake, which together sent more than 100 black legislators to Raleigh, mostly to the lower House, over 30 years.

James Youman Eaton (1864-1928), member of NCGA, Vance County, 1899

And while they never represented a politically powerful presence—they were always a small minority within their party, which held majority legislative power only briefly between 1868 and 1875, and again from 1895 to 1898—as around 20 black legislators did serve in each of the 1868, 1870, and 1883 assemblies, followed by roughly a dozen more in the sessions of the late 1890s.

I wrote about the 1883 contingent in a 2009 article for the North Carolina Historical Review (“The Class of ‘83: Black Watershed in the North Carolina General Assembly”) and found out some fascinating facts about both the 19 men—three state Senators and 16 House members—and the era in which they were elected. Just over half of this one group had attended college, and one even held a master’s degree, a rarity for most legislators of either race in this still-rural, agricultural state.

NCGA member Aaron Bridgers (1854-1929) was completing his legal studies when elected in 1882. Like his colleagues, his political experience was minimal—only four of 19 had served previously, all retiring after 1883—and for all but another four, it would be the last time they served. Bridgers soon moved to Winston-Salem, where he practiced law for decades.

It was an era when most Southern states, all controlled by the Democratic party, were considering ways to make it more difficult for black citizens, all registered as Republicans, to vote—devising poll taxes and literacy tests—in order to depress the opposition’s vote totals. North Carolina was not yet dominated by the white supremacy movement that finally took power in 1898, and the actual elections were still reasonably fair—a relative term, admittedly, but evidenced by the sizable number of blacks still winning political office at the county level—although the General Assembly would soon begin experimenting with ways to restrict voter registration itself.

Of the 128 elected to the General Assembly by 1898, most were born before the outbreak of the Civil War—and most, though not all, were born to enslaved families. A smaller number, including Leary and White, were raised by free families of color, which accounted for about 10 percent of the state’s pre-War African American population. On average, they were at least as well educated as their white counterparts—almost all were literate—although public education was only available to black students after the War.

George Lawrence Mabson (1846-1885)

Member of NCGA, New Hanover County, 1870-1874

Those who went on to attend college—generally at private universities like Biddle University (now Johnson C. Smith), or at Howard and Shaw Universities—were more likely to have work experience as schoolteachers or ministers. The six lawyers in their ranks—Bridgers, Eaton, Leary, Mabson, White, and Williamson—remained politically active in the party after serving, although only White sought and won higher office. Robert Williamson (1864-1931), a Biddle University graduate elected to one term in 1892, would unsuccessfully seek the office of Second Judicial District solicitor, the post previously held by George White, in 1894 and 1898; he practiced law in Milton and New Bern for decades.

Onetime Howard University student John Leary, born in 1845, moved from Fayetteville to Raleigh, then Charlotte, where he practiced law until his death in 1904. George Mabson, another Howard alumnus, was reputedly the first African American admitted to the state bar; he practiced law briefly in Wilmington before his early death at age 40 in 1885. James Eaton (1863-1928), a Shaw University graduate, was a longtime fixture in legal circles in Henderson and Vance County, serving as a school principal and as county attorney at one point.

By 1900, the first era of active participation by black legislators had come to an end. The five black legislators elected to the General Assembly in the 1898 elections were the last to serve for more than half a century. The state’s voters passed a controversial constitutional amendment in 1900, imposing a literacy test on all potential registrants, but one almost exclusively aimed at black voters; illiterate white voters with a male ancestor able to vote in 1867 were exempted, under the so-called “grandfather clause.” (Because free blacks lost the vote in North Carolina in 1835, almost no potential black voter could claim that exemption—and the complicated new literacy test used after 1902 was easily manipulated to disqualify even well-educated black applicants when the county registration board so chose.)

Voter registration numbers among black men in North Carolina soon dropped drastically, from an estimated 80,000 or more in 1895—a majority of the state’s Republican party membership—to perhaps 5,000 in 1905. The next black legislator elected in the state would be Henry E. Frye of Guilford County in 1968—a longtime legislator who later became chief justice of the state Supreme Court in 1999.

Henry E. Frye (born 1932)

Member of NCGA, Guilford County, 1969-1982

But in a truly quirky twist of history, Frye had been forced to go to law school just to gain the right to vote. Refused as technically illiterate in his hometown when he first applied—despite already having graduated from college, and having served as an officer in the U. S. Air Force in the 1950s—he enrolled at and graduated from the all-white UNC-Chapel Hill law school in 1959. He was finally allowed to register to vote, without objection, soon thereafter.

Next time: An obscure black hero saves a President, but cannot save himself …