The forgotten state of Franklin—and those who wish to remember it

History gets obscured in the shadowy details

Years ago, I wrote a term paper in graduate school in a constitutional history class about the U.S. state of Franklin—the one that died a’borning, on the western edge of what is now North Carolina—between the time of signing of the U.S. Articles of Confederation and the admission of the larger State of Tennessee, under the newer Constitution in 1796. It is a freakish bit of history—full of strange twists and turns that different historians treat differently, depending on which side of the line they reside.

Much of it revolves around a compellingly strange politician named John Sevier, who led the motley group who declared independence from North Carolina in 1784, after enduring what they considered second-class political status in the state’s westernmost frontier for too long. North Carolina’s western border at that point was still the Mississippi River, with the western half largely unsettled wilderness. Franklanders—for the proposed first name was “Frankland”—were in danger of becoming stateless, when North Carolina ceded the unsettled portion back to the Confederation Congress (later rescinding that decision). Afraid of being sold to Spain or France, desperate residents wrote their own constitution—a revised version of North Carolina’s—before elected a state assembly of sorts, and tried in vain to enlist the favorable support of Benjamin Franklin by offering to name the new state for him.

Map of ill-fated State of Franklin. Courtesy, N.C. Department of Cultural Resources

The aging statesman and Founding Father may have been flattered, but he was not impressed enough to consent to that action—or the new state—before his death in 1790. The Confederation Congress still fitfully governed the 13-state nation in that period before adoption of the current Constitution, but even it was lukewarm to the idea of a 14th state. In the end, only seven of 13 states approved the Franklin request, when approval required nine votes; North Carolina abstained. After the failed vote, North Carolina immediately began threatening to use its militia against the renegades, who audaciously covered all bets by continuing to send legislators to the state General Assembly after 1784.

John Sevier soon became the first governor of Franklin, which fought a battle or two with North Carolina militia, with a bounty on Sevier’s head. He then fell out personally with another Franklin leader, developer John Tipton, who disavowed the idea, and soundly thrashed Sevier in a street encounter in Jonesboro, the capital. The new state continued in a kind of political limbo until 1789, when Sevier was elected to the North Carolina Senate—apparently while still in jail—and a solution of sorts was devised. Give the Tennessee lands—all of them—to the new Congress, which entertained statehood requests under terms of a new clause in the newly-adopted Constitution, inspired by the Franklin fracas.

By 1796, Tennessee was admitted to the new Union, albeit as the 16th state, after Vermont and Kentucky.

* * * * * *

Many others have told the story more completely than I can here—or did in my graduate paper, which was told through the imagined voice of the illustrious Benjamin Franklin. There was even an East Tennessee PBS documentary about 10 years ago, “The Mysterious Lost State of Franklin,” and many scholars—mostly in Tennessee—still add to the mystique with papers and presentations. The viewpoints may vary, depending on sympathy for Sevier or Tipton—and North Carolinians remember it far less fondly, perhaps, than Tennesseans.

It did start me ruminating about the reasons why some states came into existence—but others did not make it. Franklin was not the last “failed” state, by far. Four more proposed states rose and receded over the next two centuries—Deseret, Sequoyah, Absaroka, and Jefferson. You can trace their histories in a mini-documentary on the History.com website (https://www.history.com/news/5-would-be-u-s-states). Others may yet come before us. Who knows how long our flag will continue to have 50 stars?

Deseret, a huge swath of the West, was first proposed in 1849 by Mormon settlers in what soon instead became Utah Territory, and piqued my interest the most. (It died, in part, because the Mormon practice of polygamy was anathema to most Americans.) My father’s family hailed from Utah—and my own great-grandfather was jailed, briefly, for refusing to divorce either of his polygamous spouses before Utah finally became the 45th state in 1896.

Sequoyah, proposed by a large group of Indian Territory residents in the early 20th century, was similarly unable to gain traction, probably because Congress declined to entertain the idea of a separate new state run according to tribal practices of five Native American Nations. Instead, it was folded into the new state of Oklahoma, admitted as the 46th state in 1907.

Absaroka, the wistful brainchild of a group of Wyoming secessionists led by former baseball player A. T. Swickard, came close to breaking through just before World War II—Swickard appointed himself governor, issued license plates, and began holding “court” in 1939. The new state also included parts of Montana and South Dakota, would have featured landmarks like the Grand Tetons and Yellowstone National Park. But it faded away almost as quickly as it appeared.

The most recent one was Jefferson, which inaugurated its “governor” three days before Pearl Harbor Day in 1941—and then disappeared, inevitably, into U.S. war preparations. It was sparked by highway-hungry activists in copper-mining counties in northern California and southern Oregon. Its state flag was the most memorable of all: a double-X, symbolizing their perceived “double-cross” by politicians from both states.

* * * * * *

Other new states may yet succeed in following their lead, although I shake my head at the prospects for either the Douglass Commonwealth—which Washington, D.C., leaders have long proposed to replace the federal District of Columbia, and which lingers on life support (in my opinion, it requires a very unlikely amendment to the U.S. Constitution, regardless of what Democratic leaders insist)—or the equally implausible State of Puerto Rico. (Voters in the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico periodically toy with choosing between outright independence—financially unsustainable—or becoming a U.S state and losing exemption from federal taxes and all its current subsidies—or staying as they are, so far the sanest option.)

Stubborn fantasists persist in believing that the state of Texas can and should become five states (see https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/more-150-years-texas-has-had-power-secede-itself-180962354/ for a 2017 Smithsonian Magazine article on the subject). Imagine the political implications of 10 sitting Senators from Texas, instead of just two!!

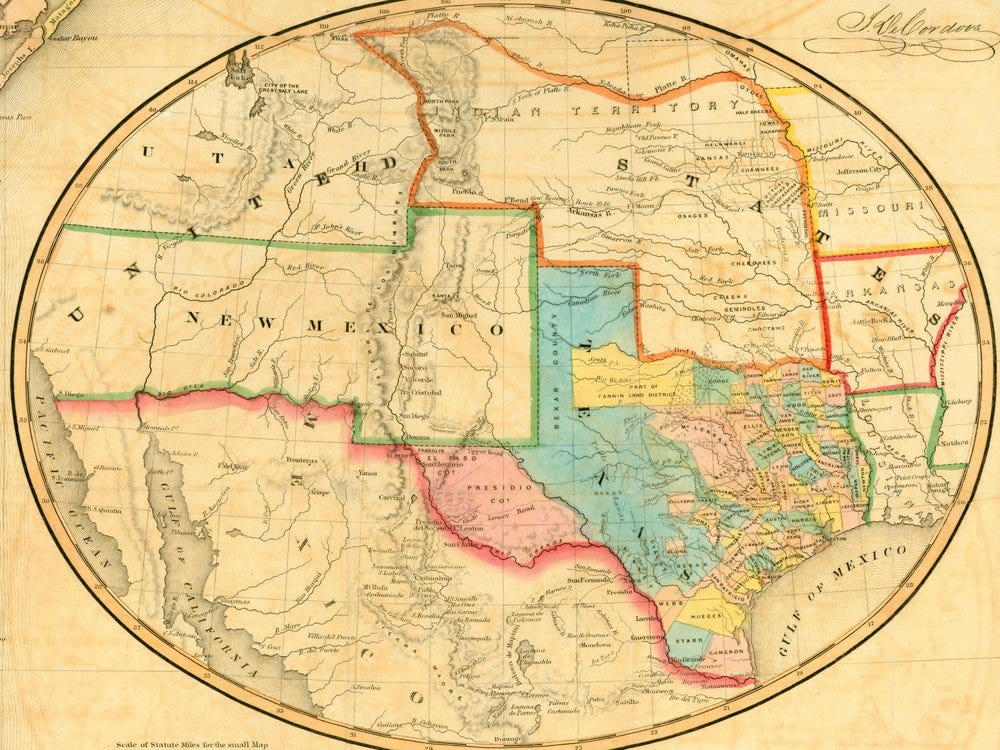

An 1851 U.S. map showing Texas and the New Mexico, Utah, and Indian Territories.

Courtesy, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas

And there are a few Californians who would like to subdivide their own huge—and to some observers, wildly dysfunctional—state in three or more states (a la the Draper plan in 2018). Imagine adding even four more Senators from California to the prevailing partisan madness in Washington, D.C.

As a child, I remember watching in fascination as the territories of Alaska and Hawaii finally became U.S. states—the first new states admitted since New Mexico (47) and Arizona (48) in 1912. I still sympathize, historically, with the romantic native Hawaiians who wish to have their “stolen” kingdom back, and the ghost of its last queen, Liliuokalani, who begged U.S. leaders to reconsider its status and undo the injustice. At least we bought Alaska fair and square from Russia, when the Tsar did not want it any more.

Queen Liliuokalani, last monarch of Hawaii. Courtesy, Library, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

And I remember the somewhat checkered wartime history of West Virginia, which had its first state capital in (Union-occupied) Alexandria, Virginia, where I once lived—because it was the only “secure” portion of the Confederate State of Virginia, from which the wannabe state had recently seceded after the Civil War broke out in 1861, in seeking to join the Union, finally, in 1863. As I recall, its first proposed name, Kanawha, was discarded for reasons that are not clear—perhaps confusion with the county of the same name or growing disenchantment with Native American state names. (Imagine trying to sing, “Country roads, take me home, to the place I belong—Kanawha”…)

More states? Please, God, no. Not when most Americans can’t even name the 50 they have…

Next time: More tales of North Carolina’s 19th-century African American legislators

Ben,

A very interesting read: You amaze me with your knowledge of history and your ability to put things and thoughts into words. Your buddy, Vince

PS: Just finished reading your article at 0608 this morning. Woke up at 0513 this morning and started reading items on my cell phone.