Sifting through the past for nuggets of historical truth

Part 2: I begin to answer all my own questions about George White … and solve most, if not all, of the puzzle

Last time, I introduced readers to my sometimes obsessive quest for all things related to George Henry White, and how I got started down the road of biographer-cum-detective-cum finisher of historical jigsaw puzzles. Five books later, I cannot seem to walk away from it.

In 2001, I published my first book, what I expected to be the definitive biography (An Even Chance in the Race of Life) of George White, thanks to the fine folks at LSU Press in Baton Rouge. I soon found, of course, that not everything he had said or written had actually made it into the biography, so I started an even more quixotic project. In 2004, I self-published my edited compilation of his writings, speeches, and letters (In His Own Words, on iUniverse.com.) That should have done it. But the strange allure of research drew me even deeper into his life and work, as I headed back into graduate school for my Ph.D., leading to an exploration of the civil rights organization he helped found and then helped lead, for a time: Broken Brotherhood: The Rise and Fall of the National Afro-American Council, which Southern Illinois University agreed to publish in 2008, with my undying thanks.

Along the way, I published periodic articles in the North Carolina Historical Review, Washington History, and any journal or magazine I could interest in my related research. I spoke to whatever group would have me. I began working with nonprofit foundations pursuing his legacy with concrete programs and educational activities. I wrote the script to a short 2012 documentary, American Phoenix, about his life. I tried my hand at an analysis of his search for his own identity, and how he had been mentored along the way by dozens of teachers, friends, family members, and political allies. It fell to the wayside. Not enough of a market out there …

But I could still feel another book-length project always taking shape, through several fits and starts—and by 2020, I managed to refine it and produce Forgotten Legacy: William McKinley, George Henry White, and the Struggle for Black Equality. It retraced the obscure, odd-bedfellows relationship between the President and his “prophet”—the name I gave him for his 1901 “farewell” speech in Congress, in which he predicted the eventual return of black Americans to Congress—during their years together in Washington. Again, the fine folks at LSU Press produced that book, earning my eternal gratitude—especially after having reissued An Even Chance in the Race of Life in 2012, this time in paperback with a foreword by now-former Rep. G. K. Butterfield, who represented much of White’s old district in North Carolina—and whose papers are now housed at Wilson Library at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Former Rep. G. K. Butterfield donates his papers to Wilson Library, 2022. Photo courtesy Jon Gardiner/UNC-Chapel Hill

But even after manfully fleshing out the story of how George White collaborated with William McKinley on an unfulfilled journey toward racial equity and justice, I wasn’t satisfied. I still wasn’t finished—and was soon talked into researching and producing a manuscript history of the small town in New Jersey which he founded in 1903, Whitesboro, and his legacy of entrepreneurship and self-help. It was fun. (That should appear in print soon.)

I suppose I should now just let the subject rest in peace. What else is there to say, after all, about George White? I may be past my prime, anyway—running out of the stamina it takes for even one more book. Is there really any demand for more about a man about whom so few people have still ever heard of, after 20 years of my earnest efforts?

As a side project, to keep my academic blood pumping, for years I have been compiling short biographical sketches of the 125 or so so black men who, like White, served in the North Carolina General Assembly between 1868 and 1900—some for as many as five terms—and faded away into political obscurity after the sea change of 1900: the constitutional amendment which deprived so many black men of the right to vote. It keeps me busy between other projects … so maybe that is the book I should write instead.

But I have this nagging sense that George White may still deserve at least one more book … perhaps a comparative study of his psychological struggle to mediate the philosophical divide between his early twentieth-century rivals, Booker T. Washington of Tuskegee Institute and W. E. B. Du Bois of the Niagara Movement? (I sense a real snorer there …) Should I instead resurrect and complete the unfinished book on his identity and how he formed it? At least that sounds lively …

Or maybe, I should attack a sensational study of his dysfunctional relationship with the younger president who took over from William McKinley—Teddy Roosevelt, the man who declined to hire George White for a job he was eminently qualified for after he left Congress, and the reasons why. For all his fascinating virtues, and much-vaunted accomplishments, was Roosevelt at core an egomaniac, who disliked people who challenged or stood up to him, as White may have—or perhaps, even a barely-reconstructed racist, who thought blacks were simply inferior and trusted only a select few? Was it something George White did or said?

Or perhaps, the fault for their estrangement lay more outside the Executive Mansion, as I strongly suspect it might, and with Booker T. Washington: Roosevelt’s gatekeeper, for the African American community, who simply did not like George White—for reasons he kept to himself? Would I ever be able to find a compelling answer? Would anyone even be interested—or receptive? Or would publishers just reject even a veiled attack on “our Teddy”—hero of San Juan Hill, peacemaker of the Russo-Japanese war, and winner of the undeclared, posthumous Battle of Mount Rushmore?

Much thorough research is called for, a task unceasingly critical to answering such questions. Yet without White’s private papers, which I have never located, and suspect his younger widow simply jettisoned after his death in 1918, I may never know for sure what other people wrote him—and I have searched most of the relevant collections of major players of the era in vain for any letters he might have written them with any real insights. That is what research boils down to, after all—perspiration and unrewarded eyestrain and backaches driven by stubbornly naive optimism. I love it … the rare disappointment is just a part of the game.

In truth, I suppose I am just a prisoner of my own love of research, digging into archives and libraries and as-yet-untouched collection of other people’s private papers and letters. So what has my research been like? And why does it take me so long?

* * * * * *

I began my research on George White seated at a microfilm reader in the University of North Carolina’s Wilson Library, poring over reels of microfilmed newspapers, mostly from North Carolina, between the 1870s, when his career began, and his death in 1918—especially the Tarboro Southerner, the New Bern papers, and the Raleigh Gazette and News and Observer. In case you have never used an old-fashioned microfilm reader, you cannot fully appreciate the combination of thrills and pure exhaustion—eyestrain, backache, and feet gone to sleep—that are awarded the explorer by this particular type of research.

Louis Round Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Photo courtesy University Communications, UNC

I soon gravitated over to the wonderful North Carolina Collection held by Wilson Library, where I found George W. Reid’s doctoral dissertation from the early 1970s at Howard University, “A Biography of George H. White, 1852-1918”—chock full of useful information and tantalizing leads. And I soon discovered the astounding book—not surprisingly, published by LSU Press—by Eric Anderson that helped me understand the political environment in which George White came of age: Race and Politics in North Carolina, 1872-1901: The Black Second.

I had barely scratched the surface. But armed with these guides, microfilm printouts, and legal pads full of scrawled notes, I might soon have branched out to other libraries and archives—notably, the state archives in nearby Raleigh—to begin fleshing out my master’s thesis at N.C. State (political science) or UNC dissertation in journalism (I was pursuing both programs simultaneously) when everything was put on hold. The U.S. State Department unexpectedly offered me a commission as a junior Foreign Service Officer, and I jumped at the chance to live overseas, after a few months training in Washington, D.C. So everything went into a footlocker, following me around the world to Kingston, Copenhagen, Washington, Paramaribo, Singapore, and Riga … and finally, back to Washington.

But I never did go back to Chapel Hill to finish my graduate studies. Life kept getting in the way. Between postings, I spent six months learning Danish, then a full year learning Russian for a two-year stint in the Nuclear Risk Reduction Center as a Russian-designated disarmament watch officer. Overnight, a dozen years passed. In 1996, while serving as an international relations officer, I found my old research self finally coming up for air. At lunchtime every day, I started going instead into the stacks of the State Department’s convenient library, where I found the bound volumes of the Congressional Record for those years George White had served in Congress (1897-1901)—and started the laborious task of tracking and copying his speeches, bills, and voting record.

And almost as if by magic, I was back in my element. By the end of 1997, I wanted to devote even more time to my research—and write a book about George White. So I traded in my Foreign Service ID for a stronger pair of reading glasses and headed out into the real world again. Over the next two and a half years, while working almost full-time as a freelance editor, I began spending more and more time at the National Archives and the Library of Congress, in between trips to libraries and archives in North Carolina—Chapel Hill, Raleigh, Greenville, Tarboro, and New Bern—that I already knew, and now in Philadelphia—where George White had lived for the last 12 years of his life, and where I saw the first microfilmed copies of that city’s Tribune, a black weekly newspaper which mentioned George White frequently in the 1910s.

The Archives held a veritable treasure trove, from microfilmed U.S. census records, city directories, and Freedmen’s Bureau records—essential to understanding the first public schools open to students of color after the Civil War—to original manuscript collections of President McKinley’s administration papers and the Booker T. Washington papers, among two very helpful resources. I started keeping a written record of each new lead—even if it was unlikely—to George White, and constantly updated a list of questions I still had—and where the most likely location of an answer lay.

The main U.S. National Archives building, downtown Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy David Samuel

Inside the Library of Congress complex, I became a devotee first of the Main Reading Room in the original Jefferson Building. There, I encountered bound copies of a wide variety of original books from White’s era—including some written by White’s friends and contemporaries, and one for which White himself had contributed an original article, as well as an invaluable three-volume index (Black Biography, 1790-1950, eds. Burkett, Burkett, and Gates) that led me in so many different related directions at once. I found and compared dozens of biographical sketches of White in contemporary Who’s Who-style compilations—some with details I had not uncovered myself elsewhere.

The magnificent reading room of the Library of Congress, Jefferson Building, Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy Shawn Miller

In the Library’s separate, far more modern Madison Building, I found many more magazines and newspapers on microfilm—particularly the Washington Colored American and Bee, and the New York Age—and began poring over the larger mainstream white newspapers, especially the Washington Evening Star, which frequently reported on White’s Congressional activities and his visits to the White House—and occasionally, the New York Times and Washington Post, which paid somewhat less favorable attention to him than its cross-town competitor.

I visited the Moorland-Spingarn archives at Howard University, where George White had gone to school in the 1870s. And in between trips, I wrote letters to anyone who might have something I wanted. So I wrote Oberlin College, where his daughter had attended the school’s conservatory soon after 1900—and Lincoln (Pa.) University, Case Western Reserve, and Penn, where his son had later gone to school and law school. I wanted to know more about Whitesboro, New Jersey, the town named for him, which he had founded in 1903. So I wrote the widow of a longtime resident who I heard had once written a town history—and ended up becoming fast friends instead with her sister-in-law, a retired Philadelphia physician who had actually known his daughter Mamie, and served as executrix of her estate (in 1974). Beginning with Odessa Spaulding, who died in 2008, I began cementing ties with past and current residents of her hometown in New Jersey’s Cape May County, which I soon began visiting.

The 1901 newspaper advertisement which attracted many new settlers to Whitesboro, N.J. Colored American, Public domain

I was hopelessly hooked, and stayed busy. I followed up every possible lead. I checked out every possible detail, then double-checked it for accuracy. My rewards eventually included the name of George White’s hitherto-unmentioned fourth wife (Ellen Avant Macdonald)—and a number of his letters to newspapers that helped flesh out his private opinions and post-congressional life.

Looking back on that period, I am still not sure how I got any paid work done—and how I managed to get anything else done but research. But somehow, I did produce a couple of draft chapters that attracted the attention of distinguished historian Bertram Wyatt-Brown, editor of the Southern Biography Series at LSU Press in Baton Rouge—who indeed thought it might be a perfect addition to the Press list.

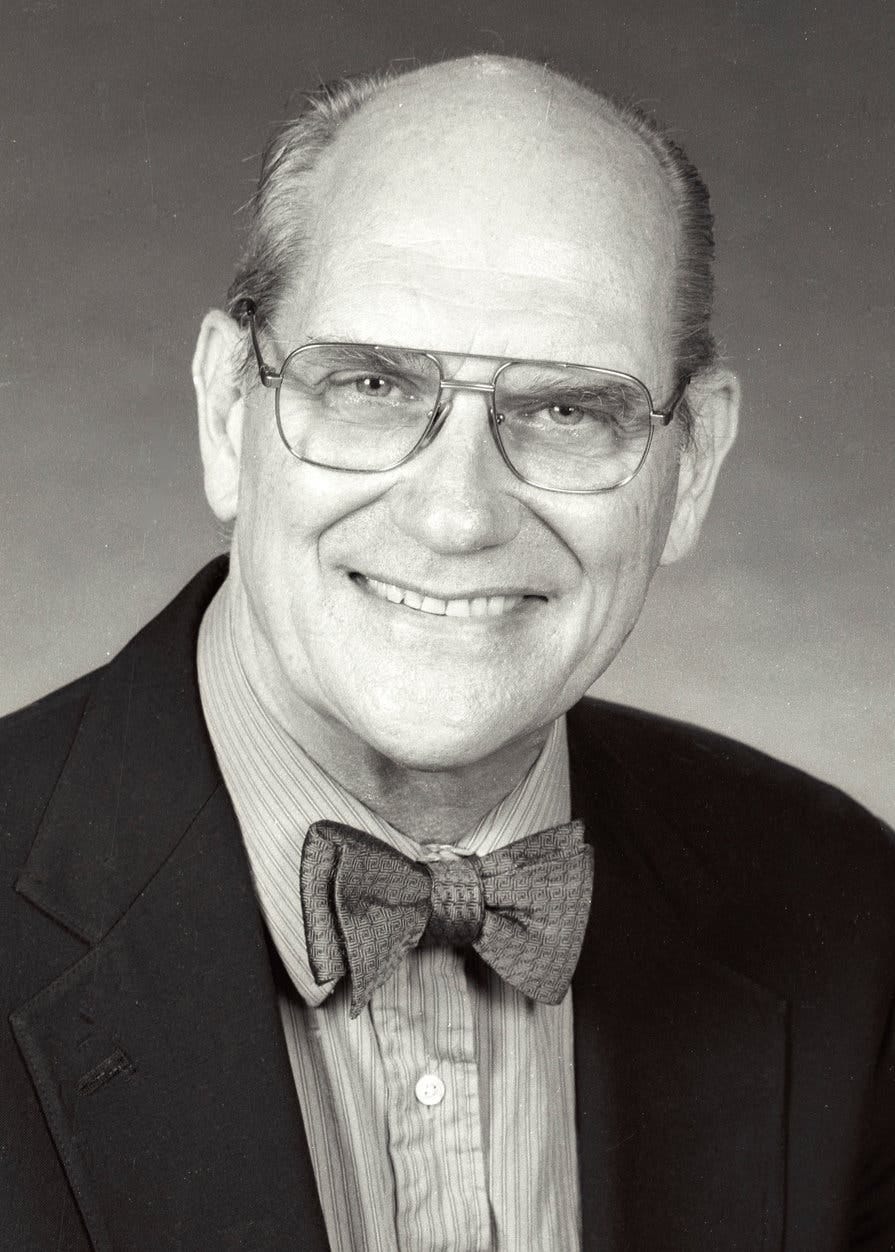

Bert Wyatt-Brown, without whose encouragement my first book would not have appeared. Photo courtesy University of Florida

It came out, under his gentle, firm pressure, in early 2001, and was even nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in biography. Along the way, Bert and I became good friends, as well, lasting until his death in 2012—just before its reissuance.

Cover of the 2012 reprint edition of George Henry White: An Even Chance in the Race of Life.

Even after the book was finished, I could not stop chasing down details of the life of George White—and inevitably became involved with two nonprofit organizations equally interested in promoting his legacy: Tarboro’s Phoenix Historical Society, led by my good friends Mavis Stith and Jim Wrenn, and the Benjamin and Edith Spaulding Descendants Foundation, thanks to my other good friends, Vincent Spaulding and Milton Campbell.

Even as I approach a possible retirement, I simply can’t imagine living without doing some kind of regular research—even if much of mine has necessarily been confined to my home computer and the Internet, especially since the advent of COVID-19. (But in this age of digitization of almost all paper records, that has hardly caused even a hiccup.)

I am still a bit of a masochist, however, and would love nothing more than to get back in front of a real microfilm reader … if just for the thrill of victory, and even enduring the agony of de feet (and de back) …

Next time: More tales of North Carolina’s 19th-century African American legislators