Sifting through the past for nuggets of historical truth

Or, completing a high-stakes historical jigsaw puzzle

More than 25 years ago, I set out to reconstruct the life of a nineteenth-century African American politician I had encountered as a young journalist, on my way to graduate school, because I could find no adequate biography of him.

It took me years of patient digging to paint a reasonably full and fair portrait of George Henry White, the last nineteenth-century black man elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, as well as the first to serve in that body in the twentieth century, before he retired in 1901. My biography of White appeared a century later, in 2001, and getting it into shape for publication was like assembling a puzzle with missing pieces—so I became a detective, investigating countless red herrings and dead ends.

Much of the misinformation recorded relentlessly by previous historians about him, portrayed him, almost perversely so, as the “last former slave to serve in Congress”—and more darkly, as a dangerously militant troublemaker during his four years in Congress—among other things.

After spending more than three decades immersed in White’s past, I can still find no mention of this so-called “fact” about his slave birth before his death in 1918—not by him, nor by anyone who knew him—or any contemporary validation of his supposed militant attitudes, other than his introduction of a bill prohibiting lynching in 1900, or his many speeches on the House floor denouncing lynching. And for those actions he was widely praised (outside the South, at least). It only became fashionable by historians to use both newer characterizations after he was no longer around to respond to them.

I doubt George White would necessarily have been cared about or been offended by the description of his supposed birth in slavery, although it can neither be proved nor disproved. Why do I think that? I am convinced it made no difference to him. Because so many of the 19 or so black congressmen before him had actually been born into slavery—just over half, as I recall. He was born in 1852, almost a decade before the Civil War started. So it was a natural mistake, perhaps, for those who knew nothing about him—or about free blacks at all—but still, he never claimed otherwise. He knew the truth about his background, and he was a remarkably private man.

Rep. George H. White (R-NC) (1852-1918), member of Congress from 1897 to 1901. Photo courtesy Odessa Spaulding

But the truth, as always, is far more complicated than most ever learn. For George White’s father was a comparative rarity—a free man of color, employed as a manual turpentine laborer by another, more prosperous free man of color, whose daughter he married when his son George was four years old—and White was thereafter raised in a free household. The name and legal status of his birth mother are nowhere recorded; she is presumed to have died soon after his birth. All he ever said was that he regarded his stepmother, Mary Anna Spaulding White, as his natural mother, and she treated him as her own son, pushing him to obtain a real education.

It was, of course, far easier for later historians to paint him as a freed slave than to waste time explaining the complicated circumstances of his free upbringing. Up to 10 percent of North Carolina’s African American population were actually legally free in 1860—even if no one really wanted to talk about it, except John Hope Franklin—but giving even a limited nod to that context required a lengthy explanation. It was far easier to generalize, as well as one more subtle way to demean his accomplishments. So George White became just one more emancipated slave—if perhaps much brighter and far more accomplished: a college graduate, schoolteacher, lawyer, legislator, and elected prosecutor before entering Congress—but still, in the end, just another ex-slave made good.

* * * * * *

The militancy charge was harder to explain. But the philosophical environment of George White’s day was already being polarized quickly, as black leaders found increasingly themselves forced to choose between two ends of the new political spectrum: with educator Booker T. Washington’s conservative “bootstrap” philosophy at one end and activist W. E. B. Du Bois holding down the far more radical viewpoint at the other end. George White knew them both, and worked alongside both. But he took neither side, preferring to chart an independent course somewhere between the extremes. He remained committed to justice and civil rights, but without the rancor of so many of their colleagues on either end of the new spectrum, while he preached the virtues of hard work and education.

W.E. B. Du Bois (left) and Booker T. Washington. Photos courtesy WGBH-TV, “Booker T. Washington vs. W.E.B. DuBois.”

This is not to say George White had no contemporary detractors, for he did—both during and after Congress, particularly at home, and even within his own race. One rather infamous critic was an outspoken newspaper publisher in Raleigh, a Democratic party leader who took delight in loudly mis-characterizing every speech given in Congress by his Republican arch-nemesis, George White.

Part of the shrillness of Josephus Daniels’s relentless reporting on George White in the daily News and Observer grew out of Daniels’s determination to excoriate all things Republican—as an apostle of the burgeoning white supremacy movement staked out by Democrats in North Carolina during that period, he was also eager to help defeat the nation’s last African American member of Congress, whatever it took. As it turned out, accomplishing that took changing the state’s Constitution to create a new “literacy” requirement for registering to vote—and ensuring that far fewer black voters could take advantage of the newly-enacted loophole used by illiterate white voters to qualify: the widely-ridiculed but legally palatable “grandfather clause.”

Because George White vehemently opposed the amendment itself, aeven campaigned against it, he became a sitting target for Daniels and his merry band of like-minded, white supremacist Democrats. That Daniels himself loudly denounced lynching—as an unlawful and dangerous practice, and not in keeping with Southern civilization—was beside the point. His paternalistic viewpoint demanded that whites and whites alone should control the system and manage its excesses—and that ungrateful black voices such as that of George White should be marginalized and silenced.

He relented slightly when White died in Philadelphia at the end of 1918, enough to allow a vaguely positive front-page obituary for the former congressman to appear—20 years after welcoming menacingly hateful cartoons onto the same front page had hounded him into retirement. Daniels eventually apologized, a bit, for his role in stoking the flames of white supremacy in 1898, when a political firestorm toppled the elected Republican-led government of the state’s largest city, Wilmington, under the guise of destroying what he blithely and disingenuously called the “Negro domination” of state politics.

Josephus Daniels (1862-1948), publisher, politician, and nemesis of George White. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Yellow journalists like Daniels—sensationalists whose regard for the truth is often obscured by their pandering to the masses—tend to get respectable if they live long enough, just as the popular saying predicts for “politicians, ugly buildings, and whores,” so famously said the fictional Noah Cross in the movie script of Chinatown (a phrase often understandably misattributed to Mark Twain—a Daniels contemporary, if not friend—who certainly inspired it philosophically.) So it was that a thoroughly disreputable scoundrel like Josephus Daniels came to dominate the political landscape long after George White stepped off the national stage in 1901.

A favorite of the Democratic party, for all his hayseed-style bluster, Daniels was a trained lawyer with a keen intellect—and served as Secretary of the Navy during World War I for one U.S. president and U.S. ambassador to Mexico for another during the runup to World War II, dying only at mid-century. His long life, influential newspaper, and well-regarded autobiographies lent his questionable views on race far more credibility than they merited, so it is perhaps not surprising that historians of the periods routinely began to mimic his personal distaste for George White in textbooks.

I first wrote at length about the feud between them in an article which the North Carolina Historical Review (“George Henry White, Josephus Daniels, and the Showdown over Disfranchisement, 1900”) published in 2000, previewing a chapter from my forthcoming book (George Henry White: An Even Chance in the Race of Life, LSU Press, 2001). Daniels was still something of a legend in North Carolina when I was growing up in a town just south of Raleigh in the 1950s, where the News and Observer was virtually required reading. And if his old newspaper was still quite popular, its historical ties to white supremacy had faded away; the “Old Reliable” had long since become one of the South’s more liberal spokesmen on racial matters, editorially, even while state textbooks still echoed the lingering myth that nothing good had ever come out of Reconstruction in the South.

But until 1975, I never heard a mention of George White in any North Carolina history course I took. I never even heard his name until I had to write a newspaper article about him. That was when I got hooked…

* * * * * * *

Back then, I was a staff reporter at the venerable Fayetteville Observer—one of the state’s larger and most respectable (oldest) afternoon dailies—and my managing editor handed me a press release from the state history museum in Raleigh. It was near the high point of the early Civil Rights era, and a handful of black Southern politicians had only recently achieved the unthinkable: election to Congress, among them Georgia’s Andrew Young and Texas’s Barbara Jordan. So now the state’s history museum was staging a retrospective exhibit on the four black North Carolinians who had previously served in Congress nearly a century before. Come again?

I had recently met Andrew Young at a speech in Fayetteville, a truly impressive guy. I was aware that he was not the first black congressman—many, in fact, had been elected from outside the South since 1928—and I had, of course, watched Barbara Jordan, enraptured by the commanding strength of her voice, on the TV screen during the Watergate hearings. But I knew nothing of their nineteenth-century predecessors.

Rep. Andrew Young (D-GA), 1977. Photo courtesy U.S. News & World Report Magazine Collection/Library of Congress.

Rep. Barbara Jordan (D-TX), ca.1975. Photo courtesy Bernard Gotfryd Photograph Collection, Library of Congress

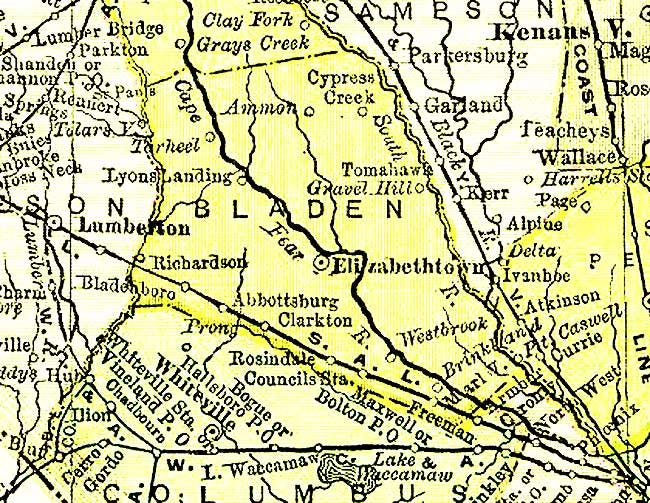

So this was startling news to me—where on earth had these men even come from? Because I had only two hours to dig up as much of a local angle on the press release, I did the best I could in those days before the Internet and search engines—in the local library and on the telephone. The four men—John Hyman, James O’Hara, Henry Cheatham, and George White—had actually served a total of seven terms between 1875 and 1901, in a congressional district in another part of the state. The Second District —once regularly called the “Black Second”—lay in the rural northeast, stretching from New Bern up to Warrenton, Henderson, and Tarboro, much nearer Virginia than my own southeastern corner along the South Carolina line—but one of them, George White, had been born in nearby Bladen County, which lay within our circulation area.

White, Cheatham, and O’Hara—all trained lawyers, like Josephus Daniels, as I would later discover—had actually been well-known national politicians during their four years each in Congress; Hyman, who served one term, had been largely ignored. They were also all Republicans—unlike the Democrats who had replaced them since 1935. Expanding the press release to include the new details I found, I finished the article, with a couple of small hasty errors—for one, the town of Rosindale, where White was listed as born, actually did still exist, if reduced to a fading railroad crossing in a largely forgotten corner of Bladen County—and a sharp-eyed reader soon upbraided me for suggesting otherwise.

Bladen County map, showing Rosindale in almost direct center (below Clarkton). Courtesy Mary Richardson, coordinator, North Carolina History Project

I never made it to Raleigh to view the exhibit, but something about George White stuck with me, doggedly. Perhaps because I had actually lived in the Columbus County town of Whiteville, not far from the Columbus-Bladen line, before coming to work in Fayetteville. And I had spent so much time at Lake Waccamaw and Hallsboro, near where he had actually grown up in Welches Creek Township. So our physical paths had actually crossed—if a century apart—and we somehow seemed destined to meet again. Even after I left active journalism for a brief business career, he rumbled around in the back of my mind. The North Carolina state highway historical marker program put up a marker to him in 1976 in New Bern, where he had once taught school and practiced law before moving to Tarboro, where he lived while in Congress. He received sporadic mentions in the press. He faded back into obscurity.

New Bern’s 1976 marker to George H. White, noting “born into slavery.” Photo courtesy North Carolina Highway Marker Program

When I started graduate school in journalism several years later at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, George White became, inevitably, my spiritual sparring partner, as it were, as I cast about for possible subjects, first for a master’s thesis, later for a doctoral dissertation. The more I dug into his past, mainly in microfilmed newspaper pages from around the turn of the twentieth century, the more confounding my search became—and the more misconceptions, inconsistencies, and inaccuracies I discovered in the historical record. Even the closest thing yet to a biography of White—a doctoral dissertation completed a decade earlier at Howard University, from which George White himself had once graduated—was not immune to small errors and misinterpretations, despite the diligent research performed by its author, now a professor who had actually published journal articles about White in the 1970s before moving on to other pursuits.

When would someone get around to correcting and amplifying the historical record, once and for all? Who would have the time to do it? Would any publisher think it worthwhile to tackle such an unknown subject? And perhaps most importantly, would anyone else even care?

Next time: I begin to answer all my own questions about George White …