Secretary of State Shultz Visits Soviet Georgia

Part 1: Students of history and culture take a brief vacation from foreign affairs

I have recently recounted for readers my brief trip to Kyiv, Ukraine, in 1988, as a small cog in the entourage of Secretary of State George Shultz. At the time, I was a junior Foreign Service Officer at the U.S. Department of State, assigned to the press office in the Bureau of Public Affairs, and was brought along ostensibly to shepherd the herd of journalists covering the Shultz trip across the Soviet Union.

After our half-day in Kyiv, our party flew on to Tbilisi, the capital of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic. To the best of my knowledge, it was the first trip ever by a high-ranking American official to Georgia, best known as the birthplace of former Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. During previous meetings with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and his then Foreign Minister, Eduard Shevardnadze, himself a Georgian, Secretary Shultz had expressed an interest in traveling outside the Soviet capital, Moscow. His request was granted by Gorbachev in the prevailing spirit of “glasnost” (openness).

If this trip lacked major policy substance, it nonetheless offered Shultz—and the rest of his support staff, as well as the journalists traveling with us—a rare opportunity to explore the culture and history of an exotic Soviet republic and an ethnic group in the South Caucasus which received little regular coverage in the world. The Georgians—once an independent kingdom with a long history—had been regularly occupied by neighboring empires, until it was offered protectorate status by the Russian Empire in 1783—and then annexed outright two decades later by Russia. Briefly independent after the Russian revolution in 1917, it was quickly seized and integrated into the new Soviet Union by the early 1920s.

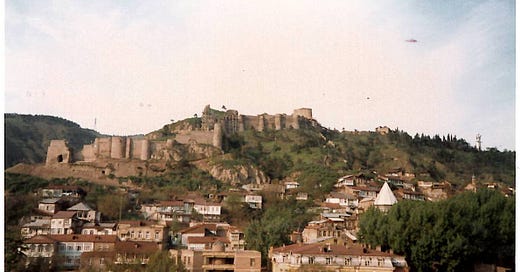

Among the first nations to adopt Christianity in the 4th century A.D., Georgia enjoys a distinctive place in world culture. Its signature fortress at Narikala, overlooking the Kura River, dates back to its construction by the Persian empire around the year 400, and many of its inner walls were constructed later by Arab emirs, who began building their palace inside the walls before 900 A.D.

Looking up at Narikala, perhaps the most popular tourist attraction in Tbilisi, April 1988. Author’s collection

Secretary Shultz and his wife, famously known as “Obie,” spent much of the day touring the city, after a festive airport reception and welcoming ceremony, complete with flowers, then a performance by local dancers, and always flanked by beaming (or scowling) local officials. Both Shultzes were avid tourists who often traveled together whenever possible, although the Secretary was more a student of geopolitical history, and his wife seemed more interested in culture.

Just off the plane from Kyiv, the Shultzes are greeted by Georgian dignitaries, April 1988. Author’s collection

Because the Secretary’s trip to Tbilisi was scheduled to last about 24 hours, the Georgian government was understandably anxious to show off as many of its tourist attractions as possible in that time period. Having found themselves in the world’s eye for the first time in decades, with representatives of the world-famous American news media covering every event, they accordingly pulled out all the stops. All four major TV networks—including the newest, CNN—were there, along with correspondents from five major U.S. newspapers, three newsmagazines, two U.S. wire services, and two foreign news agencies (Reuters and Agence France Press).

Energetic Georgian folk dancers entertain the U.S. delegation, Tbilisi, April 1988. Author’s collection

Unaccustomed to the international spotlight, Georgia proved to be quite picturesque, of a rather quiet and quaint environment, with crowds of curious onlookers gently but securely held back from the official party by Georgian security officials. A local vendor—perhaps trying to sell his trinkets to yet another group of tourists—managed to get too close at one stop, but was sternly turned away. At another stop, a local resident who was desperate to talk to someone—anyone—in the delegation was given a quiet tongue-lashing, and perhaps threatened with possible arrest if he persisted. (We saw him standing, forlornly, off to one side as we departed.)

A local vendor is carefully discouraged from approaching the Shultz party, Tbilisi, April 1988. Author’s collection

Georgian security was a bit less visible than the ubiquitous Moscow forces, who closely watched every move any American made—including the dour old keeper of the keys at my hotel, one on every floor—and who would have listened gleefully to everything said inside our unfinished new Embassy, about to be gutted after built-in “bugs” were discovered in the high-rise walls. Technically, the Foreign Ministry of the Georgia SSR—each Soviet republic was entitled to one, as I recall, in line with the fiction that each was a voluntary participant in the USSR—was in charge of the visit, with carefully choreographed backstopping provided by Moscow.

It was a distinct improvement over Moscow. Indeed, at least on its face, Georgia seemed a far friendlier place than the Soviet capital—almost every Georgian actually smiled when you spoke to them. (The only Russian I saw smiling in Moscow was its leader, Mikhail Gorbachev—perhaps determined to practice glasnost at every opportunity!) But we were carefully reminded by our training (and our bosses) to report contacts with anyone who seemed, well, “too friendly”—as the KGB (Committee for State Security) was still everywhere

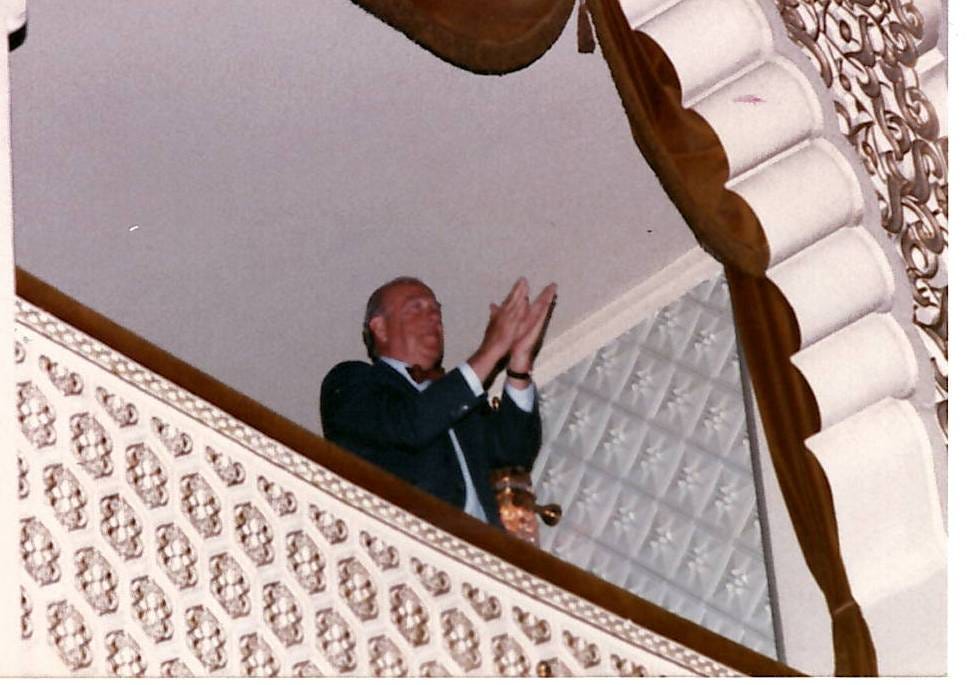

Secretary of State Shultz enthusiastically applauds Georgian entertainers from his balcony at Tbilisi State

Opera House, April 1988. Author’s collection

The highlight of the day, in my book and that of the Secretary, I think, was the night’s performance at the Tbilisi State Opera House, one of the grander buildings remaining from the Russian imperial age. First built in 1851, destroyed by fire in 1874, and rebuilt over two decades, opening again in 1896, the opera house had long served as the cultural heart of Georgia. It was formally named for Zacharia Paliashvili, one of Georgia's most revered national composers.

The musical and dance selections on that evening’s program offered something for almost everyone, from lighthearted renditions of folk labor songs to arias from well-known operas (Arlesienne, Don Carlos, Boris Gudonov) and Vivaldi selections by the Georgian State Chamber Orchestra. But the finale—a spectacular performance by dancers from the Georgian State Academic Folk Dance Company and Choreographic Company of Tbilisi School Number 3 (definitely a mouthful)—brought Secretary Shultz to his feet for a hearty round of applause. Its most memorable characteristic is “floating”—by tall women in floor-length gowns whose tiny steps on unseen feet create the illusions of gliding effortlessly across the stage in complex maneuvers with male partners. A stunning sight!

Memorial statue to King Vakhtang Gorgasili, outside Metekhi Church, Tbilisi, April 1988. Author’s collection

On Sunday morning, the Secretary was allowed to tour a number of sites, including the historic Metkhi Church, described locally as the “jewel of Georgian architecture,” first built during the 5th century A.D., destroyed during the Mongol invasion, and finally rebuilt in the 13th century. The stirring monument just outside to King Vakhtang Gorgasali, who ruled from around 447 to either 502 or 522 A.D.—no one is sure—overlooks the old city below from Metekhi plateau. [Gorgasali, a Persian term, may refer to the shape of his unique helmet, for “wolf’s head.”]

His party was then allowed to attend Sunday services at the Sioni (Zion) Cathedral of the Holy Virgin, first begun in the 6th century by King Vakhtang I and completed by his son, King Dachi, and reconstructed, after being destroyed several times, in the 15th century. I did not attend the actual service, but stayed out in the vestibule in case I was needed by the journalists outside. One of them mischievously filmed me, just as I turned around and looked back—in the only film clip of me that ever made it to TV. My recently-widowed mother, then visiting my aunt in Texas, was watching the news when her globetrotting son suddenly appeared in a network story about Secretary Shultz. What are the odds? (She claimed she almost had a heart attack!)

A brief side trip took the group to the rustic city of Gori—best known as the birthplace of former Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, then officially in historical disgrace. His childhood home and museum were routinely open for tours, though we saw no other takers. Afterwards, the Secretary and Mrs. Shultz visited several state museums as well as the studio of one of the best-known Soviet artists, Zurab Tsereteli, a Georgian-Russian painter, sculptor and architect known for large-scale and, at times, controversial monuments. His “Prometheus” sculpture (created in 1979) adorns the campus at SUNY Brockport in New York, as a gift to the United States from the Soviet government.

Tired diplomat watches his group of journalists toasting Georgian colleagues and local hospitality with Georgian

wine, Tbilisi, April 1988. Author’s collection

On Saturday night, I had been included in a banquet given by Georgian journalists for their visiting colleagues. The dinner was good enough, but I was tired after the very long day and not very hungry. I did taste the Georgian wine, which was fruity—if too sweet for my taste—but excellent, and decided to let them enjoy themselves. Just as well. By Sunday morning, I was suffering the ill effects of our Kyiv visit—as mentioned once before—and in no condition to celebrate.

Next time: Part 2: An unlucky diplomat almost gets left behind in a Moscow snowstorm

Wonderful story! I see you looking a bit worn out in the photo, but what a colorful and rare moment in history you experienced!