Searching for the pioneers in my family's past

Part 2: My great-great-grandfather Lars killed by Indians—and Great-grandpa Rasmus in prison stripes…

Last time I introduced readers to a few of my ancestors on both sides—and the sometimes colorful surprises that await genealogical explorers. My mother’s side I knew quite well, at 15—but Daddy’s side was more shrouded in mystery, including a side of his Mormon family I knew nothing about. My family was on a summer trip to visit my grandparents in Manti, Utah, when my Uncle Ern died—someone whose name I had never even heard. As large as I knew Grandpa Ben’s family had once been—eight brothers and sisters, of which he was the youngest and last surviving—I discovered there were another 10—10!—siblings waiting to be introduced …

They were all children of my great-grandfather Rasmus Justesen, a Danish immigrant who embraced his newfound Mormon doctrine with surprising vigor once he came of age in the United States in the 1860s. His parents, Lars Alexander Justesen and Karen Rasmusdatter, had been proselytized in their native Denmark in the early 1850s before making the transatlantic journey.

Undated photograph, ca. 1850, of Karen and Lars Justesen, my great-great grandparents. Public domain photo

Lars and Karen (also known as “Caroline”) brought their two surviving sons, Rasmus and Hans Peter, with them on the long journey to the Salt Lake Valley, where they made their new home in Utah Territory’s Sanpete County in 1853. But like most of the new converts to the American religion founded by Joseph Smith, he wasted no time in providing a new generation of young pioneers, taking at least five more wives before his early death in 1868—and fathering at least 10 more children.

Rasmus and his brother, Hans Peter, both served in the Utah Territorial Militia during the Indian Wars—Rasmus from May to November 1867, in Capt. J. T. Allred’s Cavalary Company—but neither appears to have been alongside their father when he died, the victim of a bullet fired by a native American combatant in Utah’s lesser-known Black Hawk War in early April 1868. (It is sometimes confused with the unrelated but more famous Illinois battles of the early 1830s.) Lars Alexander Justesen and fellow Sanpete County militiaman Charles Wilson died on April 5 in the Battle of Cedar Ridge, according to the monument raised years later.

The Cedar Ridge Battle monument, near Rocky Ford, Utah. Photo courtesy Jacob Barlow, jacobbarlow.com

According to chronicler Jacob Barlow, “a company of twenty-three men under the leadership of Frederick Olsen of Spring City were on their way to Monroe with the intention of resettling that locality. When at Cedar Ridge near Rocky Ford, now within the limits of Vermillion, they were attacked by Black Hawk and some thirty Indians. In this battle, Alexander Justesen and Charles Wilson were killed…”

Lars, 49, left behind at least four wives, my great-great-grandmother Karen having died in 1866. His families remained for a time in Sanpete County, where some of them are now buried in the Spring City Pioneers cemetery, near Lars. His later wives included Eliza Elvira Allred (1826-1875, m. 1854), with whom he had two sons; Mathilde Jensen (1840-1892, m. 1857), with whom he had at least five children; Jerusha Smith Edwards Allred (1843-1919, m. 1860), his step-daughter, with whom he had three children; and Maria Simonsen Thompson Beck (1834-1898, m. 1862), with whom he had two or three children. Little is known about a sixth wife, Annie Olsen, whom he reportedly married in 1857, but with whom he had no known children.

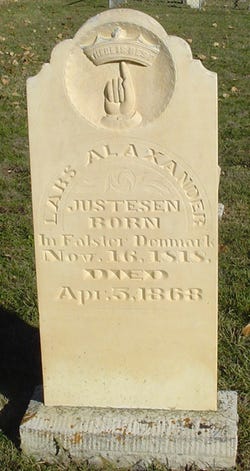

The Spring City, Utah, grave of Lars Justesen, killed in 1868 at Battle of Cedar Ridge. Public domain photo

The skirmishes dragged on for several more years, with Mormon pioneers also fighting unsuccessfully with the U.S. Congress for reimbursement of their costs in this unofficial but still deadly war. And the complicated relationship—alternately murderous and conciliatory—between the Mormon settlers and the starving Indians continued, as well, later memorialized in a striking set of statues now sitting beneath the shadow of the Mormon temple in Manti. According to sculptor and historian Jerry Anderson, the monument depicts “a Native American and a pioneer couple, originally dedicated in 1997, and was moved to its current location in 2012. We have no proof of who these figures are,” but they could represent Chief Wakara (Walker), who met with Mormon leader Brigham Young in the late 1840s, before the war broke out.

The Manti monument to Native Americans and Mormon settlers. Photo courtesy of Jerry Anderson

* * * * * *

After his own father’s death, my great-grandfather Rasmus never made the move to Monroe, having begun his own family in Spring City some eight years earlier. Around 1860, he had married a young English immigrant named Sarah Ann Shepherd, with whom he had nine children over the next two decades, and for whom he built a large house in Spring City about 1875. Rasmus’s brother, Hans Peter Justesen (1843-1929), married after 1865 and had at least 10 children; he moved to nearby Chester.

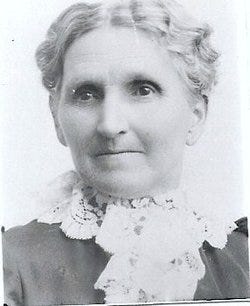

A pint-sized dynamo—under five feet tall, next to her husband, who stood well over six feet—Sarah Ann Justesen was probably less than ecstatic when Rasmus took on the responsibility of a second wife, Anine, who later became my Uncle Ern’s mother. She was a devout Mormon, and accepted church dictates, however grudgingly. But at least Sarah Ann was not forced to live in the same house with Anine and her own brood, as were the junior wives of many less prosperous polygamous families.

My great-grandmother, Sarah Ann Shepherd Justesen (1842-1933). Public domain photo

I have often wondered how the dynamics of plural marriages actually played out, and how the senior wives actually treated the junior wives. In my family’s case, the tensions were at least relieved by physical distance. Sarah Ann would have known Anine Marie Larsen (born in 1859) since she was a toddler, the daughter of the local Mormon bishop in Spring City, and barely older than Sarah Ann’s oldest daughter, Sarah Ellen, who was born in 1862.

When Rasmus took Anine as his second wife in 1875, he was immediately “posted” to another fledgling town called Castle Dale, about 40 miles east, then farther east to adjacent Emery County in the 1880s. For more than a decade, he commuted between his two families. The well-to-do sheep rancher served on the Spring City town council in the 1870s, and as the small town’s mayor on two occasions.

The 1880 census listed him as head of his farming household in Spring City with wife Sarah, and eight of his soon-to-be nine children: Sarah E., Rasmus Orlando, Joseph A., John F., Orson, Charles, Osmon, and Edith V. Justesen, still an infant. (My grandfather, the ninth, arrived in 1882.) Another young woman named Maria Justesen, 20, listed as a daughter, was almost certainly a half-sister, niece, or other relative.

Although polygamy flourished for a time in Utah Territory, first openly, then underground, national political leaders in Congress were increasingly dismayed at the legal implications of the unusual practice—certainly not legal anywhere else in the United States, and explicitly prohibited in their constitutions by nearby states, like Idaho, before their admission to the Union.

For nearly 30 years, beginning in 1862, Congress passed a series of laws aimed at outlawing polygamy in Utah, with little discernible effect. According to the Utah History Encyclopedia, it all came to a head in 1890.

All of these pressures had an impact on the church, even though they did not compel the Latter-day Saints to abolish polygamy. Church leaders as well as many of its members went into hiding--on the "underground" as it was called--either to avoid arrest or to avoid having to testify. Mormon Church President John Taylor died while in hiding. His successor, Wilford Woodruff, initially supported the continued practice of polygamy; however, as pressure increased, he began to change the church's policy. On 26 September 1890 he issued a press release, the Manifesto, which read, "I publicly declare that my advice to the Latter-day Saints is to refrain from contracting any marriages forbidden by the law of the land." The Manifesto was approved at the church's general conference on 6 October 1890.

Rather than resolving the polygamy question, however, according to one historian: "For both the hierarchy and the general membership of the LDS Church, the Manifesto inaugurated an ambiguous era in the practice of plural marriage rivaled only by the status of polygamy during the lifetime of Joseph Smith." Woodruff's public and private statements contradicted whether the Manifesto applied to existing marriages.

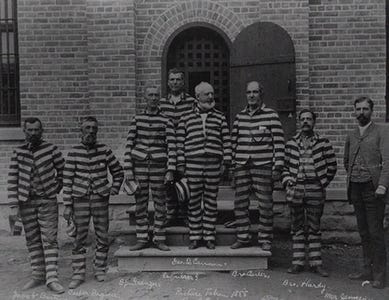

The practice itself had never been universal in the Territory, and some Mormon leaders were technically prosecuted and jailed simply for “cohabiting” with a woman to whom they were not legally married—much easier to prove, apparently, than actual bigamy. The circumstances which led to Rasmus Justesen’s arrest and imprisonment around 1890 are not clear, but one memorable photograph found in the Book of Rasmus does show him with a group of fellow polygamist convicts. That particular image is not available as I write, but the Utah History Encyclopedia depicts a similar scene from 1888:

Polygamist prisoners, Sugar House State Penitentiary, Utah, 1888. Photo courtesy Utah History Encyclopedia

The chronology is a bit murky, but sometime between 1891 and 1893, Rasmus was discharged from prison, after being pardoned by President Benjamin Harrison, and swearing to halt his practice of polygamy. This is the gist of a document contained in the Book of Rasmus. I have read elsewhere that to obtain the pardon, Mormon husbands were required to renounce all but one wife—whatever was required legally to pull that off. The majority of Mormon polygamists had just two wives, like Rasmus, so at least that was somewhat simpler for Rasmus to manage than for unlucky others. For its part, the state agreed to stop sanctioning any new plural marriages, and the church officially discouraged the practice.

But Sarah Ann remained his legal first wife, and there is no record of a formal divorce or annulment of either of Rasmus’s marriages. It is therefore likely that state officials simply turned a blind eye to plural marriages ordained by the LDS Church before 1890, as long as the offenders were discreet about their lifestyles. How faithfully he adhered to this new mandate is not clear, for Anine soon returned to live in Spring City—where my great-grandmother Sarah Ann had always lived—after 1895. He and Anine also had three more children between 1893 and 1902. So he had effectively abandoned my great-grandmother as his primary wife, at least.

Utah was also in the process of finalizing its transition from U.S. territory to U.S. state, as explained in a 1963 article in Utah History Quarterly. Congressional action had legally all but disemboweled the Mormon Church, in laws upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1890, and Church leaders saw their only chance of long-term survival as public acquiescence to the unfriendly federal mandates:

In the election of 1892, it was clear there was a two-party system in Utah, and the Utah Commission recommended amnesty to all offending Mormons. On the 4th of January 1893, a presidential pardon was given [by outgoing President Benjamin Harrison]. Confiscated properties were gradually returned to the church. … There was now passed in Congress the Utah Bill, signed July 16, 1894, by President Grover Cleveland as our Enabling Act. For the first time in her history, Utah was invited to become a member of the Union, asked to hold a constitutional convention, and write her own constitution and apply for admission!

In November of 1894, convention delegates were elected. The Constitutional Convention was held between March 4 and May 18, 1895. On the 5th of November following, the people went to the polls and ratified Utah's Constitution and elected a Congressman, state officers, and members of a state legislature. All this having been done in good order, the Utah Commission certified the results to the President of the United States, and on the 4th of January 1896, President Cleveland proclaimed Utah the forty-fifth state in the Union.

By 1898, Rasmus brought Anine and her children back to Spring City—in a separate house he now built for her—and was once again elected mayor, indicating his continuing acceptance by fellow townspeople. So after coming out of prison, he had clearly made a serious choice. Sarah Ann was well beyond her childbearing years, and perhaps he still wanted more children. Perhaps she eventually threw him out. Perhaps he flipped a coin. We will never know for sure.

At any rate, the 1900 and 1910 census listings contain his name as the head of Sarah’s household, which still included one daughter, Edith, 20, and two sons—Rasmus Orlando, 35, and Benjamin, 17, my grandfather—in 1900. In 1910, Sarah would tell the census taker that all nine of her children were still alive.

Meanwhile, Anine Justesen’s 1900 and 1910 listings describe her as the married head of her own household. In 1900, that household included one son—Ernest, now 13—and four daughters: Clara, 16; Nettie, 10; Leah, 6, and infant Alta. In 1910, Ernest and Clara had moved out, but Nettie, Leah, and Alta remained, along with newcomer Bernice, born in 1902. In 1910, Anine told the census taker she had been married for 37 years, and that seven of her 10 children were still alive. (Ironically, she lived just down the street from her husband’s son Charles, born to Sarah the same year Anine married his father.)

In 1906, her absent husband Rasmus was among a list of applicants sent to the Secretary of State as Utah applicants for medals for their military service during the Indian Wars. A decade later, he died at age 75, in 1917, proudly listed in contemporary obituaries as a “Patriarch,” and leaving 16 children still alive—and, of course, two wives.

And even though his gravestone contains the names of both wives, apochryphal family legend indicates that my feisty great-grandmother may never have entirely forgiven him for his choice. On the day of his death in October 1917, Sarah Ann reportedly refused to attend the funeral for her onetime husband, choosing to rock on her front porch instead as the procession rolled by.

She lived on until August 1933, aged 90. Her competitor, Anine, died in 1942, aged 83.

Gravestone of Mormon Patriarch Rasmus Justesen (1842-1917), Spring City, Utah, noting both wives. Public domain photo

Next time: The other half of my father’s pioneer family: the Maxfields