Searching for the pioneers in my family's past

Part 3: The other half of my father’s pioneer family: the Maxfields of Canada

In previous posts, I have examined the members of my mother’s family ancestors—especially the Wilsons and Cookes, descended from England and Wales—and my father’s paternal ancestors, the Justesens, from Denmark, who settled in Utah. This week, I look back at my father’s maternal ancestors, the Maxfields, who also ended in Utah, after a chance accident at sea derailed them from their original destination.

I have never been lucky enough to visit Prince Edward Island in Canada—still at the top of my bucket list—although my niece Laura and her husband Brian recently beat me to it, with a bicycling vacation across that beautifully scenic slice of Maritime Canada. There they actually spent time in the local archives, doing a little hands-on research into the lives of the Maxfield family, who ended up there in 1818 after being rescued from a shipwreck off Nova Scotia.

They were the forbears of my Grandma Ba—Blanche Maxfield Justesen—who was born in Utah in 1895, and spent much of her life as a gifted schoolteacher, after raising my Daddy, his sister Elaine, and brother Craig in Manti, Utah. I was never fortunate enough to discuss her family at any length with Ba—she mentioned her late grandmother only once, in one of my last conversations with her in a North Carolina nursing home in the early 1980s. Her fantastic memory was slipping away slowly by then, along with her eyesight and health in general, but Ba was still able to remember some things as she neared her death at 90.

Sadly, Ba died just as I entered upon my second Foreign Service posting in Copenhagen in the fall of 1985, before I could come back home to report to her on what I learned about her Danish ancestors. Her mother, Anna Louisia Larsen, was born of Danish immigrant parents in Utah, and married George Spaulding Maxfield in the early 1890s.

George’s father was Richard Dunwell Maxfield, the first of my British immigrant-stock ancestors actually born in PEI—in 1831, and the second son of John Ellison Maxfield and his wife, Sarah Elizabeth Baker. The Maxfield name was a fairly old one in England, with this spelling traced back as early as 1615—with the birth of Peter Maxfield—and previously, under the ancient spelling of Macclesfield, to around the 12th century.

John Ellison (1801-1875) had been born in Yorkshire, England, at the turn of the 19th century; he arrived in Canada with his parents about 1818, and then married Sarah Baker, a native of Prince Edward Island, about 1827. But Prince Edward Island had never been their destination—far from it—and except for bad weather, the Maxfield and Justesen clans might never have been united, and I would not be around to tell their story.

* * * * * *

The family records I have seen do not name their ship, which sank at sea between England and Canada. I suspect there were dozens or hundreds of passengers rescued by a passing freighter. (Elsewhere, I found the recorded wreck of at least one possible contender, the Lord Nelson, off Nova Scotia in August 1817, with at least 280 passengers rescued—but there were so many shipwrecks that it is impossible to know for sure.) A 20th-century family chronicler, Alice Maxfield Johnson, gives us the general details she discovered in putting together her family history in the 1960s:

“Early 1800s. John Ellison Maxfield, with his parents and family, left Yorkshire, England, on a sailing ship bound for Australia. They had a grant of land there. However, the schooner sank at sea. They were picked up by a passing ship and off-loaded at Prince Edward Island, which was the first landfall. The family prospered.”

The teenager’s parents were John E. Maxfield (1762-1836), a prosperous merchant, and Hannah Appleton (1767-1846). John Ellison was the sixth of their 11 children, all born in England between 1792 and 1808. How many of them left England with their parents is not known—at least two died young, and one son remained behind—so it was probably the seven youngest children. Soon after their arrival in Canada, John Ellison’s older sister, Mary, born in 1798, became the first to marry, in February 1819.

What inducements the British government had given their father to make the perilous, six-month-and-more sea journey to Australia—either around South America’s Cape Horn or Africa’s Cape of Good Hope—are not recorded, beyond the mentioned grant of land. But the land itself was a generous enticement—until 1825, “each male was entitled to 30 acres, an additional 20 acres if married, and 10 acres for each child with him in the settlement at the time of the grant,” according to the Historical Records of Australia, 1.1.14. (With seven children, his prospective amount came to 120 acres.)

Australia, of course, is better known for its original population of British convicts, who began arriving in 1788, but Sydney and Hobart, in Tasmania, had also been attracting small numbers free settlers since 1793. Although the settlement near Sydney, in New South Wales, was still widely described as “mostly inhabited by the uncivilized natives,” the continent’s population was again growing with new settlers—as well as new convicts—after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815.

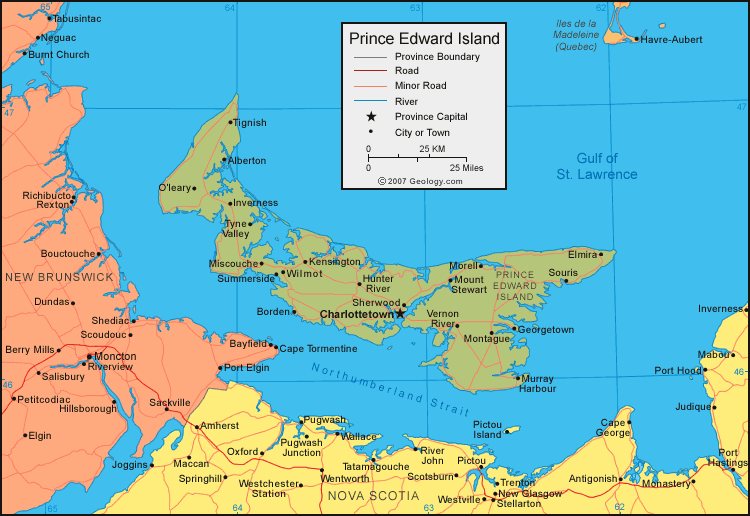

Prince Edward Island had been British for barely a half-century when the Maxfields put ashore, after its transfer by treaty in 1763 from the French. Once called Saint John, it was renamed after King George’s son in 1799; its population was still rather sparse, totaling just 9,676 in 1806, with “some Acadians, some loyalists, some English, Scots, and Irish,” according to Encyclopedia Britannica. Land was still widely available on the island’s 2,000-plus square miles, and the rich soil promised fertile crops, despite the brisk, cool maritime climate. Its tiny capital, Charlottetown, was named for Queen Charlotte, the King’s wife.

An 1811 map of St. John’s Island, now known as Prince Edward Island. Engraving courtesy J. Cary, A/ NEW MAP/ OF/ NOVA SCOTIA, / NEWFOUNDLAND &C./ FROM THE LATEST AUTHORITIES.

Modern map of Prince Edward Island, Canada’s smallest province.

If starting over in Canada seemed something of a disappointment, John Maxfield wasted no time in putting down new roots, and by the early 1840s, his enterprising family owned 600 acres of rich farmland, a growing stable of thoroughbred horses, and their own lumber mill and shipbuilding business in the Wilmot Valley around Bedeque. He died in 1836, before his family chose to make the next move—this one for purely religious reasons.

Graves of John E. Maxfield (1761-1836) and Hannah Appleton Maxfield (1767-1846), Bedeque, Prince Edward Island.

Photo courtesy Findagrave.com

As practicing Methodists in England, the Maxfields had long remained a minority among the island’s predominantly Roman Catholic population until visitors from another Canadian island, Nova Scotia, brought the intriguing news of another faith only recently unveiled in the United States to the south: Mormonism. The Maxfields were among a number of island converts to the new religion, whose missionaries were already recruiting proselytes in Canada and Europe, preparing the way for an eventual mass exodus—first to the U.S. community at Nauvoo, Illinois, and later, under pressure of anti-Mormon violence, to the western U.S. territory called Utah and the “New Zion”: the Great Salt Lake.

The appeal of the strange new religion was unmistakable among the more adventurous converts, some of whom already had large families and envisioned a well-structured new life among the ranks of the Latter-Day Saints. For John Ellison Maxfield, who attended lectures by the visiting missionaries and then proceeded to convert his own family, the promise of a better life must have seemed irresistible—so much that he chose to name his next son and ninth child, born in January 1847, after the recently-martyred Mormon leader, Joseph Smith. Family tradition records his sentiments after the conversion lectures as follows: “I’ve just heard what I have been looking for all my life.”

John Ellison Maxfield (1801-1874) and his wife, Sarah Elizabeth Baker (1811-1894). Public domain photos

It took nearly four years after Joseph Smith Maxfield’s birth for John’s family to complete their preparations to join the trek to Utah, including the birth of their 10th child, Quincy Benjamin, in June 1849. In mid-1850, the Maxfields departed Canada forever, together with John’s brothers, William and Richard, and their families.

According to Alice Johnson, “the families had planned to build a ship in which to sail to Chicago (Fort Deerborn at that time), but instead chartered a ship and left Prince Edward Island in June, 1850. John and Elizabeth left their large farm unsold with instructions to their attorney to sell it and forward them the money. They never heard from their attorney again. The rest of the property was disposed of with the exception of a horse. The morning they were to sail, the horse was brought around to the front of the Inn and John asked for a bid. He got the highest bid from a minister who bought it.”

Prudently, they did take a bucket of gold coins with them. They arrived in Chicago by sailing up the St. Lawrence River as far as they could go, then up one of the smaller rivers to the Great Lakes, then sailing across Lake Michigan to Chicago. They would have had to travel overland from Chicago to the now-famous Mormon settlement called Kanesville, Iowa—soon to be renamed Council Bluffs—on the east bank of the Missouri River. The family reached that town on July 9, 1850, if three weeks too late to join the last caravan west for 1850, but Johnson theorizes that Maxfield “must have decided to cross the Missouri River and go over to Winter Quarters that same day,” rather than wait even one more day.

If so, it was a fateful decision with tragic consequences: “Jesse, their fifteen-year-old son, was drowned in the river as they were being ferried across. He had been sent to get something for his baby brother who was sick; he slipped off a plank into the swift running water and was never seen again. Jesse's year-old baby brother, Benjamin, died a few days later on July 15. Sarah was heartsick.”

At Winter Quarters—the town now called North Omaha, Nebraska—the Maxfields buried their son Quincy, while raising a second stone to his lost brother Jesse. It was here that they spent the winter, waiting for favorable weather in the spring, when John Ellison’s brothers and one of his nephews all died of disease. Of those families, only Richard’s teenaged son, named John Ellis Maxfield, departed the following May 1 with his aunt and uncle, for Utah.

But Sarah Maxfield was already pregnant with her 11th child, a son who would be born near Hams Fork, Wyoming, on September 1. She and Henry Aldheimer would remain there while she recovered from childbirth, but her husband and most of her other children would proceed the final 200 miles to their destination without her, after a day or so, sending back for her only when they had reached the new Zion.

Impatient, as always, he simply could not wait to see his third, and final, home. And for John Ellison Maxfield, the next two decades would be the most productive of his life, as he labored to help build the foundation of the mammoth Mormon temple at Salt Lake.

Next time: The Maxfields reach South Cottonwood—and my great-grandfather, George Maxfield, is born

Ben

Very interesting story. Thanks for sharing. Vince