Remembering the USS Maine, and a lost baseball team …

Black pitcher William Lambert, a peacetime casualty with a bright future ...

The sinking of the USS Maine in Havana harbor in February 1898 lit the fuse which led, inexorably, to the brief Spanish-American War. If some doubt still exists as to whether the explosions that ripped through the visiting dreadnought ship were intentional or a terrible accident, the end effect was nonetheless a grievous loss: more than 260 U.S. sailors died, victims either of the outright blasts, of terrible burns suffered, or of drowning as the ship sank.

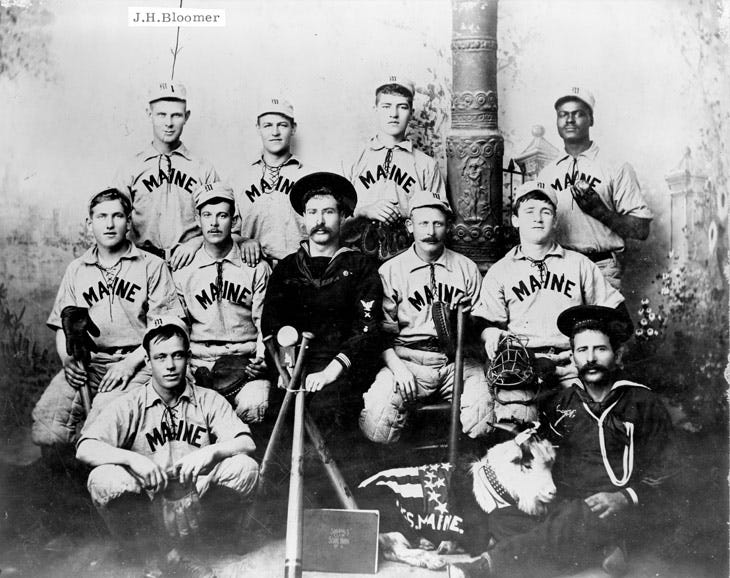

The USS Maine’s U.S. Navy championship baseball team, 1898. Pitcher William Lambert is at top right.

Courtesy Library of Congress

Perhaps the saddest of all was the loss of all but one of the U.S. Navy’s reigning team of baseball champions. Less than two months before arriving in Havana, ostensibly on a goodwill tour, the Maine had been stationed in Key West, Florida, where its talented players defeated the team from the USS Marblehead in an 18-3 battle in December 1897. Only their team mascot, a goat, remained in Key West as the Maine departed in January—and just one team member survived the horrors to come.

I first wrote about the Maine disaster—and the barely-reported impact of the deaths of its 22 black sailors on African Americans in general—as well as its implications for recruitment of black volunteers in the soon-to-be-declared Spanish-American War, in my 2020 book, Forgotten Legacy: William McKinley, George Henry White, and the Struggle for Black Equality (LSU Press).

The USS Maine, as she looked just prior to sinking in Havana harbor in February 1898. Courtesy Library of Congress

The Maine lay anchored in Havana harbor for nearly four weeks, with its crewmen ferried into the city on shore passes and officers entertained by Spanish colonial dignitaries. There is even one report, perhaps apocryphal, that the baseball team was planning a match against an all-star team in Havana before its departure, which had not yet been announced—and was never held.

Shortly after 9 p.m. on February 15, 1898, a U.S. Marine Corps Fifer, C. H. Newton, of Washington, D.C., played taps on his bugle. It was the last duty the team’s talented third baseman would ever perform. When the Maine exploded and sank less than an hour later, most of its 350 crew members were killed outright, either by drowning or by severe burns; a handful died in subsequent days and weeks.

Newton and more than 260 fellow sailors died, either outright in the tragic explosion or of injuries received. Only 84 men aboard the Maine survived, including the captain—Charles D. Sigsbee, the last to leave the ship, and later promoted to Admiral—and Newton’s teammate, Landsman John Herman Bloomer of Portland, Maine, 23, who played right field.

Writer Tom Miller described the scene as follows, in his 1998 article for Smithsonian Magazine (“Remember the Maine”):

At 9:40 p.m. the Maine's forward end abruptly lifted itself from the water. Along the pier,

passersby could hear a rumbling explosion. Within seconds, another eruption--this one

deafening and massive--splintered the bow, sending anything that wasn't battened down,

and most that was, flying more than 200 feet into the air. Bursts of flame and belches of

smoke filled the night sky; water flooded into the lower decks and quickly rose to the upper

ones.

Some sailors were thrown violently from the blazing ship and drowned in the harbor.

Others, just falling asleep in their hammocks, were pancaked between floors and ceilings

fused together by the sudden, intense heat. Still more drowned on board or suffocated from

overpowering smoke.

The team’s star pitcher, Fireman First Class William Lambert, a 23-year-old African American engine stoker from Hampton, Virginia, was the team’s only black member. Lambert, like most of his colleagues trapped below deck, was unable to escape the fiery blast. And like Lambert, the team’s talented shortstop, Navigator’s Writer John Henry “Shilly” Shillington, 21—who had played college baseball and basketball at Notre Dame University before joining the Navy—appears to have died instantly, perhaps drowning in his bunk.

Other team members killed included Landsman William A. Tinsman, 21-year-old left fielder of Susequehanna County, Pennsylvania; Seaman Leon Bonner of New York City, assistant manager; Gunner’s Mate 1st Class Charles F. W. Eiermann, team manager and coach; and Ordinary Seaman William H. Gorman of Boston, Massachusetts (second base).

Three Brooklyn, New York, residents also died—Landsman Charles Hauck, 25 (center field); Landsman William L. Hough (first base); and Landsman John Merz (shortstop)—along with the team’s catcher, Apprentice Second Class Benjamin L. Marsden of Jersey City, New Jersey.

* * * * * *

Although relations between the U.S. and Spanish governments were often tense in February 1898, open hostilities had not yet broken out (that would not occur until April 1898.) As a gracious gesture, perhaps, the Spanish colonial government offered to bury most of the dead sailors—perhaps as many as 150—in the Cristobal Colon Cemetery in Havana, although it is not clear how many of those being buried could be identified by name.

Original grave of USS Maine crewmen in Colon Cemetery, Havana, spring 1899.

Cross reads "Victims of the Maine." Photo by Robert Edward Wilkins 4th Virginia Volunteer Infantry.

In December 1899, following the brief war with Spain, their bodies would be disinterred from the Colon Cemetery in now-independent Cuba and taken back for reburial at Arlington National Cemetery, outside Washington, D.C.

In February 1898, wounded survivors had first been evacuated by another ship back to Key West, where newspaper and other reports show at least nine sailors died there of their injuries. A solemn funeral procession to the city graveyard for those nine coffins was filmed by Thomas Edison’s company in March 1898, in a film now held by the Library of Congress. A total of 24 sailors—some consisting of partial skeletal remains which had occasionally begun to surface, months or years after the explosion—remain buried in the Maine section of the Key West city cemetery, at least one beneath a headstone marked as “Unknown.” (The fenced-off Maine section also holds 60 additional unrelated graves.)

Headstone in Key West City Cemetery. Photo courtesy Bonnie Gross, Floridarambler.com.

At least one contemporary news account in the New York Times described the sailors’ Florida interments as “temporary,” according to a U.S. Navy spokesman at Key West (“SAILORS' BURIAL AT KEY WEST; Temporary Interment to be Made of Maine Victims Hereafter Found -- Claims for Their Money,” New York Times, March 1, 1898), although at least some of the sailors buried at Key West remain there today.

And in a curiously ironic twist of fate, the cruiser Marblehead—whose crew had lost to the Maine team in Key West in December 1897—was sent to Cuba to replace the Maine after war broke out, remaining there for four months. Just before its departure, an official inquiry had determined—perhaps in error, as a 1970s study would conclude—that a Spanish mine had caused the explosion of the Maine. The wreck of its sister ship remained mutely visible in the shallows of Havana harbor as the Marblehead approached.

The former runner-up was now acting on behalf of its lost companion, performing duties the Maine would almost certainly have carried out instead, according to www.history.navy.mil/history :

The Marblehead arrived off Havana 23 April 1898 and then proceeded to Cienfuegos where

she shelled enemy vessels and fortifications on the 29th. After joining the blockading

squadron, she cut the cables off Cienfuegos 11 May, and then patrolled off Santiago de Cuba

until the beginning of June. In company with schooner‑rigged cruiser Yankee, Marblehead

captured the lower bay of Guantanamo as a base for the fleet 7 June, and on the 10th

supported the landing of a battalion of Marines there. Continuing operations in the bay, she

helped battleship Texas destroy the Spanish fort on Cayo del Toro 15 June.

The Maine section of the Key West City Cemetery in 2022. Photo courtesy www.keysweekly.com.

* * * * *

Few details about the lives of most of the Maine baseball team members are widely available, but Gary Bedingfield’s extraordinary research provides helpful clues at “Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice,” a website which honors former military members involved in baseball, found at https://www.baseballsgreatestsacrifice.com.

The lone survivor, John Bloomer, soon moved back to his hometown of Portland, Maine, where he had been born around 1875; by 1900, he was married with one son, according to that year’s census. But his reported addiction to alcohol—perhaps related to or worsened by his harrowing experience aboard the sinking Maine—claimed him at an early age; by March 1907, he was dead. He is buried in Portland.

William Lambert was later recalled by a shipmate as “a master of speed, curves, and control,” and might well have had a future in college athletics—at Harvard College, at least, where black players were welcomed—or even in the minor leagues, which were not yet officially racially segregated, if he had only lived past the war. One of 22 black sailors killed in the Maine explosion, out of the 30 total aboard, Lambert symbolized the rare progress still available to African Americans in the U.S. military at that moment; the U.S. Navy was technically integrated, as compared to the Army, where black soldiers could only serve in all-black units, and almost always under white officers, during the brief Spanish-American War.

Landsman Hauck, 25, was the son of Wendel and Katherine Hauck, of Brooklyn. He enlisted in the Navy on August 13, 1895, and served as a Landsman aboard the USS Vermont, before joining the crew of the Maine.

But perhaps “Shilly” Shillington’s exploits are the most documented, and best remembered. A red granite monument was erected to him in 1915 on the Notre Dame campus in South Bend, Indiana, using “metal recovered from the sunken battleship, [with] a 10-inch mortar shell projecting from its five-foot base”; it stands today near the Joyce Athletic and Convocation Center and ROTC Pasquerilla Center. The 21-year-old Chicago native attended Notre Dame sporadically from 1892 until his expulsion in 1897—for a minor infraction of school rules on a team trip to Chicago. A shortstop for three years and basketball team captain—as well as actor and prize-winning public speaker—the versatile athlete joined the Navy in August 1897, according to a family biography (www.shillington.net/remember_the_maine.htm).

Among the 230 Maine casualties now buried at Arlington National Cemetery, the names and gravestone photos of just two team members—left fielder Tinsman and manager Eiermann—can be found among the 62 sailors named in the cemetery’s computerized database. Born sometime before 1880 in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, son of a U.S. Navy veteran on the Merrimack of Civil War fame, Tinsman grew up in East Deering, Maine, and enlisted with the Navy in 1897. Eiermann was a 25-year-old native of Eberbach, Germany, and had become a U.S. citizen just three years earlier.

Minor discrepancies dot even their skimpy historical record, indicating bureaucratic confusion surrounding their burials: Tinsman’s gravestone lists his middle initial as “A,” not the generally preferred “H,” while Eiermann’s usual surname is misspelled on his stone as “Eirmann.” Yet they are among the fortunate few; at least their descendants can visit their graves. Where the bodies of their remaining nine team members are actually buried is open to debate—some, perhaps, in unidentified graves at Arlington, with others interred in Key West.

The Maine’s captain, Charles D. Sigsbee, was exonerated by a court of inquiry and later went on to command the USS Saint Paul at the Second Battle of San Juan during the war in June 1898. In 1907, he retired as Admiral from the U.S. Navy. He died in 1923, and is buried nearby, within sight of the mainmast of his beloved Maine. His 1899 book, The MAINE — An Account of Her Destruction in Havana Harbor,, was published by the Century Company of New York, among the first of many chronicles of the disaster.

Today’s visitors to Arlington can view the majestic mainmast of the Maine, installed as part of the monument dedicated there in 1915. More than 62 feet tall, the mainmast was recovered, intact, when the ship was raised and refloated; beginning in 2006, it was restored by the United States Army Corps of Engineers, the National Park Service, and other partners. The rigging was meticulously wound and now spirals up to the eagle’s nest as it did originally, while other structural and aesthetic features returned the mast to its original majesty, according to a 2018 press release from the cemetery.

Rededicated in 2018, the mast now stands guard over the bodies of its 230 shipmates for all time. There are many other memorials. Monuments featuring Maine artifacts in other locations around the country include the foremast, now displayed on the U.S. Naval Academy grounds in Annapolis, Maryland; a bow anchor, in a city park at Reading, Pennsylvania; her bow scroll, in Bangor, Maine; and her capstan, in the Battery at Charleston, South Carolina.

Perhaps the most impressive is a large, ornate sculpture at an entrance to New York City’s Central Park—a city from which four of the dead baseball players had come—at its Merchants Gate entrance, designed by Harold Van Buren Magonigle, with a fountain at its base and sculptures by Attilio Piccirili of gilded bronze figures—cast from metal taken from the ship itself—representing Columbia Triumphant, her seashell chariot being drawn by three hippocampi (mythological seahorses). It stands 57 feet high.

The Maine set two historical precedent still honored today. The Spanish conflict marked the first time the U. S. government had decided to repatriate remains of service members who died and were buried overseas, including John Paul Jones, retrieved in 1907. It also marked the first time the Arlington Cemetery had been enlarged since its opening during the Civil War. Since then, many more have come home to be remembered and revered in death, at Arlington and elsewhere.

And through the 125 years since their deaths, the men of the Maine, like their ill-fated ship, have remained in a special historical category—heroes of peacetime, both on the baseball field and off, and sadly, forever young.

But the historical controversy that brought them home, it seems, may never die. In the 1970s, one of America’s most heralded naval heroes, Admiral Hyman Rickover, chose to reopen the original 1898 investigation, using modern historical investigation techniques and consulting skilled engineers to study the records. According to Brown’s Smithsonian article, Rickover’s controversial 1976 report, which was rereleased with additional evidence in 1995, stirred almost as much furor as the 1898 Sampson Commission report—which had led Congress to declare war on Spain—despite reaching the opposite conclusion.

No mine was, in fact, responsible, said Rickover’s panel, but a horrible internal accident, “likely the result of a coal bunker fire … but whatever its cause, it was absolutely clear that an external force—a mine or torpedo—was not responsible.”

Other historians still argue, stubbornly, that a large mine—if one of still-unknown origin—was responsible. But so far, no one can explain, convincingly, why the Spanish colonial government would have mined its own harbor at Havana—or chanced setting off an unwanted war with its nearest neighbor. Conspiracy theorists in Cuba and elsewhere even speculate feverishly—bewilderingly at times, with no evidence—that the United States blew up its own ship in order to provoke the war, which the Americans won in record time, with few casualties.

Fewer than 2,500 Americans died in all during the war with Spain, more than 80 percent of them from disease, largely from yellow fever after invading the island, and not in combat. Fewer than 400 American deaths occurred as a result of actual hostilities—and that number does not include the gallant men of the Maine, who died weeks before the War began.

Next time: A white President speaks at four historically black colleges …