Remembering a cub reporter's days in the newspaper game

Part 3: After a Caribbean honeymoon, life in the wilderness ...

Last time, I brought readers up to the beginning of my third job, at the afternoon daily, the Sanford Herald, in mid-1973. I moved on to Sanford two months before my wedding, but still spent almost all of my free time back in Whiteville, where Helen and I were the featured “Bridge and Groom of the Summer” in a special advertising insert published by the News Reporter, my previous employer. That meant posing for a seemingly endless series of photographs helping tout the services and product offered by advertisers—a tiresome, if still interesting way to fill up the hours before the big day.

I had almost nothing to do with the planning (thank goodness), and Helen was, in fact, finishing up her senior year at Chapel Hill until mid-May, thus escaping most of the early work. But we were both a bit daunted by both the size and the extent of the wedding itself, and Helen’s mother would have it no other way. (If we had had our way, eloping would have been the easy way out—but sadly, such a possibility was a pure pipe dream.) A fixture in local society, her mother’s plans including sending out a total of 800—800!! I was astounded—invitations, of whom about 500 eventually attended. Half a dozen bridesmaids, eight or nine groomsmen …

By the time the wedding rolled around, we were both bleary-eyed and exhausted. The only thing that kept me going was the thought of a week on the beach in St. Croix, in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Out of my meager salary in Sanford (by now I was up to $150 a week—paid in cash!), I had saved enough to pay for an engagement ring, the flight, and a week’s stay in advance in a seaside cottage, at a place called Arawak, near Frederiksted, the westernmost and smaller of the old Danish island’s two towns, population about 1,000; the other was Christiansted.

The three Virgin Islands (Danish West Indies) were purchased by the U.S. in 1917 from Denmark. Map courtesy Wikipedia

St. Croix wasn’t a long flight away, but still almost 90 miles south of Puerto Rico, where we had to change planes from Atlanta—I later learned that there were direct U.S. flights to the St. Croix airport, but only from New York—and our last segment from Puerto Rico was in one of those 20-passenger “puddle jumpers.” It had a center aisle and one seat on each side—so we had to hold hands across the aisle. I swear the windows did not close tightly, either—I could hear the waves lapping on the beach as we landed at the small airport.

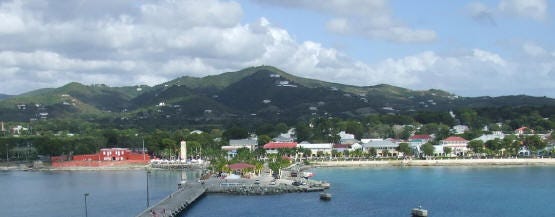

Frederiksted, established in 1751, the small St. Croix town with a big harbor! Photo courtesy Wikipedia

But it was truly an island paradise, and neither one of us wanted to go home from this idyllic escape. We had a grand time driving a rental car around the small island—about the size of the District of Columbia, with perhaps 50,000 residents—in great weather, shopping and buying souvenirs. The Crucians were friendly and hospitable. We did a little cooking at lunch in our cottage kitchenette, or ate out in town, but also enjoyed the family-style evening meals served at the “big house.” The food was good and plentiful, and the company was friendly—one or two other honeymooning couples.

But this rookie soon learned two hard traveler’s lessons: first, always take twice as much money as you expect to spend (just in case) and most important, read the fine print. I did not ask the right questions, and the Wilmington travel agent who recommended Arawak forgot to emphasize what was not covered: family-style meals in the great house. When I checked out, the manager handed me a bill for $175 worth of meals—as much as I had paid ahead for the week’s rent—and I had just $180 cash in my pocket. I had assumed it was all-inclusive. Ouch … They did not take credit cards (not everyone off the mainland did in those days), so my almost maxed-out Bank Americard [remember them?] was useless—and of course, it was too late to offer to do the dishes …

Luckily, in Atlanta, I was able to get enough cash out of an ATM to buy us airport burgers during our layover. Helen consoled me. But I was still mortified. Dumb, dumb, dumb … I had not planned things very well. My parents met us at the airport in Fayetteville when we landed there, and Daddy smiled as he handed me two envelopes—the same envelopes I had handed him a week earlier, as best man, to give the two ministers who officiated—so suddenly, there was enough cash to get my car out of the airport parking lot. Bless his heart … always my hero!

Now it was time to head back to the real world, the wilderness …

* * * * * * * *

We both had dogs, Helen having adopted a puppy who promptly got hit by a car, and survived, but always walked lopsided. Pokey and Igor became best friends—he would walk down the center of the busy highway in Whiteville to visit her in her own front yard (people would call me at work to say they had seen him)—and we decided we wanted to live in the wide open spaces when we “merged” our families. Igor, generally sweet-natured and well-behaved, had one annoying—even dangerous—habit: he hated bicycles, and would occasionally bite the ankle of anyone who rode by my yard.

After Igor bit the circuit-riding rabbi, Reuben Kesner, on his way back to the synagogue a block from my house, I was forced to start chaining him up, which I hated. (His bites weren’t bad but I had no desire for a lawsuit…) Reuben was a friend of mine, and said he wouldn’t call the police if I chained him up. I did.

So we opted to rent a brand-new A-frame house out in the middle of nowhere in Chatham County, about 15 miles from Sanford, toward Pittsboro. The noted novelist and short-story writer Doris Betts, another favorite teacher of mine at Chapel Hill, recommended her friend Paul Camp, the owner, as a good landlord. Her husband, Lowry Betts, was a well-known lawyer in Sanford; a college dropout from the old Woman’s College in Greensboro (now UNC-G), Doris eventually became the Distinguished Alumni Professor Emerita during her 30 years in Chapel Hill. [See her obituary at https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/25/books/doris-betts-novelist-in-southern-tradition-dies-at-79.html .]

Doris Betts (1932-2012), who taught me creative writing at Chapel Hill. Photo courtesy the New York Times

Paul and his family lived not far from the site, where he had already built one A-frame and was planning another—the place was wild, unspoiled and beautiful, and we both liked it. Close to Chapel Hill but no traffic. Plenty of room for two energetic young dogs and an adventurous young couple. By now Pokey had undergone her hip-replacement surgery—the vet molded her a new hip joint out of plastic!—and walked much better, if always a bit sway-backed.

But there was one big catch: our new house was three miles down a gravel road, of sorts, near the Deep River, which made commuting to and from our jobs a bit demanding in foul weather or the dark (we both had to be at work early mornings)—so we rarely ran home for lunch! We did have a terrific stone fireplace—built by hand around a wooden frame which eventually caught fire, producing a jet-engine-like WHOOSH, spewing embers all over the roof, and frightening us to death—and an extra bedroom upstairs that wound behind it. So when friends and family came to visit, only the daring ones came back a second time. It was fun—even though the well water always smelled a little like gunpowder (side effect of the explosives Paul used to dig the well).

The dogs loved the outdoors and for a few months, all was well. Then Pokey became ill—a blood clot from her early injuries finally dislodged and traveled to her brain—and had to be put down after she bit the vet, whom she had always adored—and Igor was inconsolable. I had to start chaining him up again after he bit my landlord’s teenage son on a motorcycle. Six months after we moved in, he decided to chase bigger wheels—the earth-moving machine Paul had hired to dig the foundation for our neighboring house—and I was the inconsolable one. The poor driver never saw him coming …

Helen and I soon adopted two new puppies, but we probably should have waited longer—until we could adjust to our losses. Our new female cockerpoo, Berit, was adorable, and easily trained, the hard-headed male Labrador, Maximus, not so much … and between them, they ravaged the carpet in our bathroom. And of course, life got in the way …

* * * * * *

We both enjoyed our jobs, Helen a little more than I did —a born teacher, she was teaching math and science to middle grades at the Deep River “union” school, grades K-12, in rural Lee County, smallest county in the state. Most of the students lived in the county seat, Sanford, population about 15,000 (about the paper’s daily circulation); it held roughly half the county’s population at that time and retained its own city school system (until the two systems announced a merger, soon after I moved there). Her school was in a sparsely-populated northern township, and the entire school, built in 1924, had fewer than 200 students, as I recall. [More than 50 years later, the replacement building now serves grades K-5.]

Lee County’s Deep River Union School, built in 1924, demolished in 1998. Public domain photo

My job was a true learning experience—in addition to technically having to be at work by 7 a.m. six days a week (sleepyhead here did make it by 7:30), I was also the backup AP/UPI wire editor, and when my colleague Betsy Gaster was hospitalized for several weeks, was expected to make it in by 5 a.m.—a real wake-up call (Holy cowabunga, Batman! 5 a.m.? Is that even on the clock? My freshman roommate used to come back from his morning classes and find me still fast asleep, electric alarm clock buzzing in my ear …)

I started out as the education beat reporter, and most of my stories were about the city-county school merger until I moved on to general assignments, mostly crime and traffic accidents in four counties. We had at least four reporters and a sports writer, and often traded assignments with the city editor’s blessing—and the editor, a genial guy named Bill Hodges, made working there a lot more fun than it might have been. He answered to the paper’s day-to-day assistant publisher, Bill Horner Jr., and indirectly to the founder, old “Mr.” Horner, who came in several times a day griping about something or other, never satisfied, never appreciative.

The paper was founded in 1930, and once it succeeded, he had once run for Congress—the year before I was born?—losing narrowly, never got over it. A truly crabby old guy, he was a millionaire who still pinched pennies for a living and screamed at whoever got a detail wrong in the “Rambler’s” front-page column (we all hated taking turns doing that column, which was name-heavy, time-consuming, and essentially frivolous). If he smiled once during my year there, I do not recall it. Born in 1901, he finally died in 1994, still probably too cheap to pay for a coffin … Some people grew to like the cantankerous old buzzard—said he actually had a heart, somewhere— but I refused to surrender to the Stockholm syndrome. He reminded me a bit of the holy terror villainous banker, Mr. Potter, played by Lionel Barrymore in “It’s a Wonderful Life,” one of my favorite films.

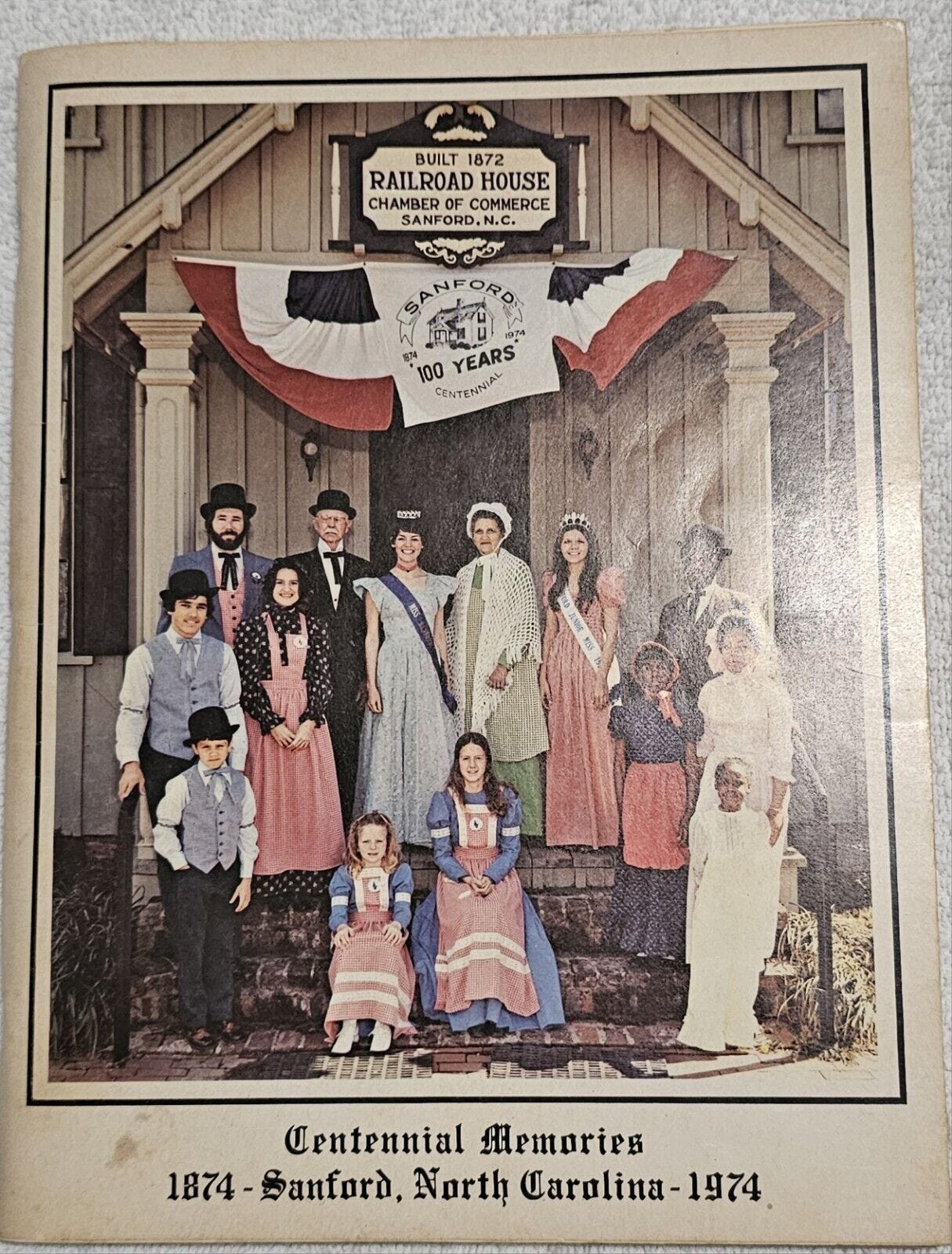

More enjoyable, at least, was the required “Champions of Central Carolina” feature, highlighting a lengthy interview with a productive member of the coverage area. I actually enjoyed doing those—it usually got me out of the newsroom for half a day at a time. Otherwise, not many celebrities or famous politicians came at Sanford in this post-Watergate off-year for elections. We did spend quite a bit of time developing a Sanford Centennial edition of the newspaper, which allowed many of us to spend time researching and writing long historical features. I still have my softbound copy of that edition somewhere. And I even got to write occasional book reviews (my specialty)!

Sanford celebrated its 100th birthday in style while I was on the Herald staff. Public domain photo

On the down side, we also got paid in cash—with a yellow carbon payslip attached to it listing all deductions—by the paper’s treasurer, who wheeled her grocery cart through the newsroom once a week, dispensing used business envelopes containing the correct amount down to the penny—Lord knows how long it took her to prepare those envelopes! Old Man Horner was far too cheap to use a bank to write paychecks …

We also got paid an hourly wage, not a set salary, and because we had to work a 45-hour week, he grumbled incessantly about having to pay us time-and-a-half for the last five hours after 40 (equaling 47.5 hours). No paid overtime after that, and so few perks that we all wondered why we even bothered—while the old millionaire sat home and counted his pennies … so when you took time off, you dropped back to 40-hour a week pay, another disappointment in the bottom line. There was no such thing as a gas allowance, particularly annoying during the OPEC oil crisis (so we sneaked into the gas station across the street for rationed gas when no one else could, thanks to a friendly station manager).

Needless to say, it was roughly akin to living in a human zoo. Turnover was rampant—the sports writer, Greg, and the columnist and former managing editor, Lois Byrd, were the only ones who seemed to have been there more than a couple of years. Lois was a living doll—a longtime friend of my great aunt’s and smart as a whip, incredibly productive even as she neared retirement age, with a distinctive typing style developed after breaking both her wrists. Another UNC-Chapel Hill alum, she commuted daily from Lillington (30 minutes each way) to the Herald for more than a quarter of a century before retiring.

Lois Tomlinson Byrd (1913-2001), a keen journalist and veteran Herald staffer. Photo courtesy Findagrave.com

Most of the rest of us were just passing through, adding experience to our resume and moving on; the pace was demanding and grueling, and the rewards were few. I really admired my boss, Bill, a rumpled but shrewd and fair guy, and did get to be lifelong friends with another newcomer, Brenda Follmer, who ended up going to work as a globe-trotting public relations director for R. J. Reynolds Tobacco, and who stayed a much-treasured pal until her early death in 2005, long after our professional paths diverged at Sanford.

I had never intended to stay for more than two years, at most. Then toward the end of my first year, two memorable events changed my life forever. I decided I needed to go back to summer school and finish my degree before I looked for another job—I had tried a correspondence course, which didn’t work out for me; I need classroom structure. So I gave Bill Hodges my notice, with a truly big dose of regret (only for leaving him). He earnestly tried to talk me out of leaving, offered to hold my job open after Chapel Hill—but no more small-town, skin-flint curmudgeons for me, I had decided.

Then Helen’s mother, Doris, became gravely ill, requiring full-time care at home. Her health had begun to collapse after she retired early, just after the wedding. So we decided to move back to Whiteville, and buy a little house around the corner from her, so she could share the responsibility with her older sister. She very easily found a job with the Columbus County school system for the following year.

I duly enrolled in summer school in Chapel Hill, after finding a furnished room there. In the first week of that five-week session, my dear mother-in-law, now in a coma, suddenly died. A sad, wrenching funeral. I did manage to finish the summer session, taking two education courses and preparing to look for a teaching job myself—after returning to our new home—when I unexpectedly landed an interview with the Fayetteville Observer, the state’s oldest afternoon newspaper, a bit stodgy by reputation, with a circulation of about 50,000, and miraculously wound up gainfully employed again.

* * * * * *

For many years, Daddy had run a retail office supply store in Fayetteville, where I had worked occasionally, and I had grown up reading the Observer, which he brought home at night to Dunn (25 miles away). But because afternoon papers were already dying out in many cities, the family-owned management had recently started up a brand-new morning edition, called the Fayetteville Times, with a separate staff, which became our in-house rival, so to speak. I actually interviewed with both newspapers, and was soon offered my preferred job on the Observer.

For a while, I commuted from Whiteville, but the 60-mile trip each way (nearer to 90 minutes on back roads) quickly proved impractical—primarily because I had to be at work by 7:30 a.m., and sometimes had to work at night, covering meetings and speeches. So I quickly rented half of a small duplex in Fayetteville from a friend of Daddy’s, and began coming home only on weekends. Helen already enjoyed her new job, and prudently, did not want to relocate so soon, but she did interview for a job in the Fayetteville city system for the coming year.

It wasn’t an ideal situation for a couple married just over a year, but we were young and flexible, and it was a step up for me. But it was also my fourth job in barely 3 years, which was not the best thing on anybody’s resume, even though I now had that all-important undergraduate degree, as well as a fast-growing clip file.

Fayetteville would, in fact, prove to be a very useful stop, but in the end, a mixed blessing, especially after my father’s heart attack in late 1975.

Next time: A real reporter, finally, until life really got in the way …