Remembering a cub reporter’s days in the newspaper game

Part 2: A winter vacation, a new dog, and a new job ...

Last time I walked readers through my first adventures as a weekly newspaper editor in the tiny North Carolina village of Shallotte, just south of Wilmington. The Brunswick Beacon started out as a summer job between my senior year at UNC-Chapel Hill and the semester I still needed to graduate, after my frequent major changes and other distractions left me just short of the finish line—but soon propelled me into a series of reporting jobs around Eastern North Carolina.

At the end of the summer, when publisher Kelvin Mackey decided to extend my appointment, I decided to move off the beach into a real house a little nearer the office—saving this sleepy-head precious commuting minutes in the morning—so I packed up my meager belongings and my newly-acquired dog, Proko, to head for Shallotte Point. A truly sweet-natured German shepherd-terrier mix mongrel, Proko—short for Prokofiev (I was fascinated by Russian history and names, and a fan of Prokofiev’s compositions!)—had been abandoned by some heartless character at my Holden Beach neighbor’s house: pregnant, as it turned out, with a litter of seven puppies on the way, and hungry. One look at those beautiful, pleading brown eyes and I was a goner.

I had never had a dog of my very own before—except for a short-lived adoption in college that failed when the puppy developed a terminal illness the first week I had him—and like my mentor, Peter Pan, I was not really prepared for the responsibilities of becoming a father myself—or a grandfather, as I discovered some six weeks later—but the 40-pound orphan, apparently badly mistreated, clung to me for dear life, grateful for any and all affection! She became my near-constant companion, until I later persuaded my parents to adopt her.

Life with Proko was simple enough; she was well-behaved and housebroken and insisted on sleeping in my bed, which was a new experience for me—her other quirk was that she stood in my lap while I drove, to hang her head out the driver’s window, I guess—a dangerous position, but she liked it. The night before I had decided to move from Shallotte Point to take a room in a Southport house rented by a friend, she disappeared. I was frantic. She finally turned up, exhausted and noticeably lighter, after having delivered her puppies unassisted at an undisclosed location during the night.

I encouraged her to take me to them and she did, willingly—after I first gave her plenty of fresh water—and I then watched her disappear again under an abandoned car, wheels off, in a field not too far from my old house. I had to go back and get a shovel to dig out a path to see under the car, where six of seven large puppies were noisily nursing. The seventh was stillborn. I placed the six pups in a cardboard box, and took them to my car; she did not growl or stop me. I returned to bury the tiny carcass—which by now, Proko had apparently eaten.

I was stunned, but later learned that was not as rare as you might think—and perhaps removing the other puppies from her weeks before I should have had been a good idea after all (some new mothers may get carried away).

Despite the minor scare, Proko turned out out to be a good, attentive mother—and the puppies were obviously from a larger father—perhaps the full-sized white German shepherd we had seen in the neighborhood before she found us? Thank goodness we had a large fenced-in backyard! By the time they were three months old, the handsome pups were almost as large as she was. So my housemate and I set out to find homes for four of the pups—she and I each wanted to keep one—and that was fairly easy! And that was how Igor (Stravinsky) became my new traveling companion—a very smart and very loyal dog who rode sitting up in my passenger seat and from a distance, at least, looked human.

The Southport house was a rambling two-story, mid-19th-century structure with a widow’s walk, facing Bald Head Island and the Atlantic Ocean beyond. Once the residence of a sea captain, it was now owned by a couple from Ohio, and reportedly haunted. Friends of my housemate, a drama student, came over one night and held a seance to find out the truth—but all we managed to do was roil the serenity of the old place, summoning up bad vibrations which woke the puppies up yelping every night for a week.

* * * * * *

Besides becoming a “new father,” I had other distractions from work—I was headed away for a winter skiing vacation in Norway. I had been invited to visit by an exchange student I had dated before leaving Chapel Hill—and Kelvin agreed to spare me for that much time! (Daddy offered to foot the bill for the airplane ticket, in part to pay me back for keeping his retail store open while the rest of the family went to visit my older brother in Germany.) It was my first trip overseas—my first time on any commercial airplane, for that matter—and I did not know how to ski. But Kari’s family was happy to host me in Oslo for 10 days, so off I went fearlessly, like the experienced globetrotter I would indeed become a decade later.

That trip was a lot of great fun, whetting my appetite for more travels abroad—if not for real ski lessons. I did learn enough to try skiing the last two miles cross-country—mostly uphill—to Kari’s family’s mountain cottage from the nearest parking lot, but fell backwards so many times that I was convinced I had no real talent for wasting my time again. Just as well. I never went back to Norway, ‘tho I did live in next-door Denmark for two years a decade and a half later. We were good friends, and stayed in touch for years, but soon married other people; curiously, we later had daughters at about the same time (1977) and gave them the same first name (Fredrika and Fredrikke).

A few weeks after I got back, I received an irresistible new job offer from the News Reporter in Whiteville, replacing staff reporter Ed Harper, who was coming home to work at the family’s State Port Pilot after a coupe of years away. (My house in Southport was two doors down from his parents’ home on East Bay Street; small world.) I think Kelvin had decided he wanted a more energetic newshound, and I was ready for a new challenge, so we parted ways amicably.

At the N-R, as part of a larger staff, I ended up assigned to a wide variety of stories—mostly covering the Whiteville and Columbus County school boards and county commission, plus local court cases, parades, and whatever special assignments the news editor, Wray Thompson, dreamed up. I soon got to be good friends with the publisher, Jim High, and Clara Cartrette and the rest of the staff, and soon enough, with a lot of people in a larger and far friendlier town. There was even a local chapter of the UNC-Chapel Hill alumni association, and it was at their annual meeting that I struck up a friendship with a junior at UNC whose mother—the guidance counselor at Whiteville High School—had dragged her along (to meet me, she and I both suspected).

It worked. Helen fell in love with my dog Igor, who had moved with me to Whiteville, and then with me; we were married a year later, moving on to Sanford and Fayetteville, where our daughter was later born. We both played bridge, enjoyed parties, and spent pleasant afternoons swimming with friends at her aunt’s lake house at nearby Lake Waccamaw (despite the presence, we discovered one afternoon, of mating alligators from the nearby Green Swamp just a few dozen yards away, in deeper water at the end of a neighbor’s long pier—I doubt you’ve never seen folks move out of the water so fast!)

A word about the small town and park at Lake Waccamaw, which is actually described by state officials as a likely meteor crater and the “largest Carolina bay.” A 2,400-acre state park for camping, hiking, and boat launching sits along part of the 14-mile shoreline of the lake, which is “one of the few craters that contains open water instead of vegetation. A limestone bluff reduces the lake's acidity, making it an ideal home for several aquatic species that are found nowhere else in the world.” [See https://www.ncparks.gov/state-parks/lake-waccamaw-state-park ]

The former railroad town was founded in the mid-19th century, and today has a population of about 1,500 full-time residents, not counting many hundreds more summer visitors and second-home owners. It is widely known for its distinctive Boys and Girls Home, founded in 1954 and serving “young people who have been removed from their homes due to abuse, neglect or other family dysfunction.”

Lake Waccamaw, North Carolina’s largest natural lake. Photo courtesy https://www.bivy.com/adventures/us/north-carolina

In between a busy social life that summer and during her senior year at Chapel Hill, I did manage to find time to produce some interesting stories—and even started writing occasional editorials for Jim to review.

One of my favorite stories involved a veteran Superior Court judge, the unforgettable James H. Pou Bailey, one of the most colorful courtroom characters of the 20th century, as well as a WWII soldier at Normandy in 1944, with my Daddy. [You can find out a lot more about “Pou,” as almost everyone called him, at this website: https://oralhistoriesproject.law.unc.edu/oral-histories/hon-james-h-pou-bailey/ .] He was presiding over a kidnapping-and-rape trial when I first met him, and was the only judge I ever knew who literally carried a pistol to court for protection.

James Hinton Pou Bailey (1917-2004), a gun-toting N.C. judge in his later years. Photo courtesy Findagrave.com

The defendant in that case was a fairly disreputable character who eventually pleaded guilty to kidnapping—but denied the rape charge, a capital offense. (I did not know the victim, a former college beauty queen, but strongly suspected she told the painful truth on the stand, while he did not; everyone believed her.) In those days, getting a rape conviction, if not impossible, was still very difficult, at best, without a confession or even less likely, an eyewitness.

As the trial neared its end, Pou and the district prosecutor, Lee Jackson Greer, were suddenly receptive to an offer of a guilty plea on the kidnapping charge, with the rape charge dropped—a ploy which the defendant had been led to believe would give him only a short jail sentence.

Lee Jackson Greer (1910-2000), a veteran prosecutor in 1972, pictured in earlier years. Photo courtesy Findagrave.com

So he stood up and said, in open court, he had had no promises made to him to entice him to change his plea from “not guilty” on both counts to “guilty” of kidnapping. I was watching from the cheap seats when Pou said, grimly, that he would now pass sentence. No need to wait for a jury verdict … so, the sentence passed was life in prison for kidnapping. (Perfectly legal sentence under N.C. law at the time …)

The defendant’s near-smirk changed to a sudden glare—he realized he had been tricked into changing his plea—and he tried an end-run around the defense table, headed for the judge’s bench, with his hands up and out in the time-honored gesture of “I’ll strangle you!” He was one big fellow, too, young, muscular, maybe 6-foot-4 and mean-looking at the best of times. Pou went for his gun … ‘tho we never saw it …

If he had made it to the bench, I am convinced Pou would have shot him dead, right there (and good riddance). He as much as told me the same thing over lunch a few days later. Luckily for both of them, a couple of burly sheriff’s bailiffs managed to subdue the defendant first, handcuff him, and drag him yelling out the door to prison. A highly-respected judge, Pou served until retiring in 1985, famous for his tough sentences and rarely overturned on appeal, as I recall.

[Read Pou’s obituary, if you have time, at http://savannah.newsargus.com/editorials/archives/2004/01/27/pou_bailey_nc_loses_a_colorful_judge/ .]

This all came back to me this past week, when a Florida defendant up for sentencing jumped over the judge’s bench and attacked her—luckily, she saw him coming and dived sideways, so was not injured severely. She did not have a gun, but did have quick-acting bailiffs, thank goodness. I don’t envy judges their “sitting target” status, and would never want to be one, but certainly admire anyone who can take the heat in today’s no-holds-barred world.

* * * * * *

I am almost inordinately proud of my Danish heritage, even if only a fraction of the folks I meet are immediately able to pronounce or properly spell my surname; even the U.S. government initially misspelled it when I joined the Foreign Service (adding an errant and unnecessary “n”). One whole distant branch of my great-grandfather’s family spells it the same way, “Justensen,” apparently courtesy of a typo by an immigration clerk in New York in the 19th century. Had the old patronymic naming system continued, my surname would never have stabilized as it is today; my great-grandfather Rasmus would have become “Rasmus Larsen (son of Lars Justesen),” and so on.

I have always tried, resolutely, to spell other people’s names correctly and consistently. But I answer wearily to anything that even sounds like mine—Justice (after the great Charley “Choo Choo” Justice of UNC football fame), or even Justiceson (??), Johnstonstein, Justinian, although I particularly detest the version favored by most artificial-intelligence voices, emphasizing the first “e” (Just-TEE-son). (I am baffled; it’s so simple, I argue—Justesen means “son of Just,” and is pronounced “Just-a-son,” which to me, at least, should roll off the tongue.)

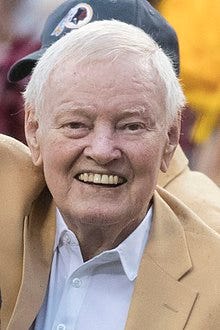

Equally proud of his Scandinavian heritage is one Christian Adolph Jurgensen III, better known simply as Sonny, originally of Wilmington, to whom I am, sadly, not at all related. Almost everyone spells his name correctly, I believe—he is, after all, famous—although I am sure some want to make him Swedish instead of Danish, with a final “o.”

In 1972, I had recently been confirmed as an Episcopalian at the tiny Saint James the Fisherman parish in Shallotte, and soon began attending Grace Church in Whitesville. The rector, a genial fellow of Irish extraction named O’Ferrall Thompson, apparently misheard my name when I introduced myself to him, then promptly relayed it to the congregation at large as “Ben Jurgensen,” apparently convinced I was related to the famous Redskins football star Wilmington. Now I was as fond and proud of Sonny as any non-Duke graduate could be, but firmly drew the line at changing my name to his.

My future mother-in-law, an English teacher with a wicked sense of humor, however, always addressed mail to me with that name, instead. Easier to spell, she said, drily.

Former pro football great Sonny Jurgensen, born 1934 and no relation, shown in 2017. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

I have since learned that while Sonny and I are not even distantly related—sign— there are more than a few “Ben Justesens” in the world beyond North Carolina, or even Utah, where my namesake grandfather was born. We have all become marginally acquainted because of the Internet. One resides in Moses Lake, Washington—a third cousin, I think—who runs a successful cleaning and restoration firm. Another is a well-known former professional cyclist in Denmark, whose friend in Greenland once sent me an email (in Danish), thinking I was his buddy. A third seems to be a medical helicopter pilot in Minnesota. I suppose one day we should get together and form a club—and recruit all the others afflicted with the same moniker—and perhaps make Sonny Jurgensen an honorary member.

Life as a newspaper reporter meant my name always appeared in bold print in bylines, where it was (almost) always correctly spelled. On my birth certificate, I am a “Second,” named for my grandfather, although I stopped using the “II” after my name sometime after Grandpa Ben died. (Too many people automatically converted it to “III,” or even “Jr.”) Except in legal situations, where every “i” had to be dotted. So when Helen and I purchased our first house in 1974, I was prepared for the inevitable typo in my name—either with the “II” or my surname—on early legal papers, and resigned to correcting it until they got it right.

What I was NOT prepared for was the hash some distracted typist somewhere made of my first name—Benjamin, the easy part—by misspelling it four or five ways in the space of what should have been a simple mortgage application and credit check … the early days of computer keyboard entries. I actually had to sign an addendum admitting that I had at one time or another been known as “Banjamina Justesen”— and almost a dozen other variations, just in case. I am surprised we actually got that mortgage …

* * * * * * *

For the first year of our marriage, we lived in Chatham County, just outside Sanford, North Carolina, where I had now become a reporter for the Sanford Herald, an afternoon daily newspaper, and Helen taught school in a rural K-12 “union” school, before moving back, briefly, to Whiteville, when her mother became gravely ill.

Next time: After a Caribbean honeymoon, life in the wilderness …