Remembering a cub reporter's days in the newspaper game

Part 4: A real reporter, finally, until life really gets in the way

Last time, I chronicled for readers how I ended up at the Fayetteville Observer in the summer of 1974, after a circuitous three-year journey around eastern and central North Carolina’s newsrooms. My then-wife and I had resettled in Whiteville, her hometown, when a sudden offer tempted me, temporarily unemployed after finally completing my elusive undergraduate degree, to move to Fayetteville.

It was a whole new challenge—a vibrant, bustling newsroom covering a vast metropolitan area perched on the promise of becoming huge, by North Carolina standards, at least, and including one of the nation’s largest military bases in Fort Bragg (now Fort Liberty)—and there were infinite opportunities for young reporters willing to scrap for stories. Back then, Fayetteville had about 50,000 residents (now, half a century later, more than 200,000) in a larger faster-growing county with other towns (Hope Mills, Spring Lake, and others). We also served readers in a large, sprawling area of rural counties adjacent to Cumberland County (today, more than half a million in the metro area).

Ashton W. Lilly (1908-2000), chairman of the Observer board after 1971. Photo courtesy Myrover-Reeese Fellowship Home

When I got there, the family-controlled Observer was led by board chairman Ashton W. Lilly and her son-in-law, publisher Ramon Yarborough; it was North Carolina’s oldest newspaper still being published. Established in 1816, it had ceased weekly publication from 1865 to 1883—after the building burned down during the Civil War—but still came back to a brighter future in the twentieth century, becoming a daily in 1896.

Fayetteville was certainly unique, and its newspaper was well-regarded—both for its progressive editorial policies and its no-nonsense local news coverage in a sleepy southeastern corner of the largely rural state. North Carolina, circa 1974, was still second in the U.S. for the number of residents living in towns of 2,500 or less, or outside municipalities completely—so even middle-sized Fayetteville easily ranked among the state’s top 10 urbanized areas (behind Charlotte, Raleigh-Durham, the Piedmont Triad cities). But it seemed and acted more like a small town on steroids, still dominated economically by the vast military reservation (40,000 soldiers and their families), with some industries making inroads.

If still more of a writer at heart than a true reporter, I was about to find out what it was like to compete for “scoops”—facing off daily with an in-house (separate Fayetteville Times) rival on our chosen education beats. Schools weren’t all I covered, but in truth, consumed most of my attention. The then-separate city and county systems enrolled tens of thousands of students, along with the smaller Fort Bragg federal system, in addition to degree-seeking students enrolled at three major institutions of higher education: the smallest, private Methodist College (now University), opened in 1960; the oldest, then-struggling public Fayetteville State University; and the newest and largest, what was then called Fayetteville Technical Institute (now Fayetteville Technical Community College), a two-year primarily trade school granting associate degrees. (I was drawn, instinctively, to the colleges.)

Then called Methodist College, the small private school still attracted mostly adult commuters in early 1970s. Courtesy Methodist University

Faster-growing Fayetteville State, founded as post-Civil War teacher training school for African Americans. Courtesy FSU

Fayetteville Tech was the busiest and largest of the three schools back then. Courtesy FTCC

I tried to cover all three evenly, although early on I was drawn to Methodist College—in part because of a largely-contrived controversy over its struggling sister school in Rocky Mount (N.C. Wesleyan College), which the church was reportedly considering closing or selling off for financial reasons—touted by some, somewhat disingenuously, as the next campus of the still-expanding University of North Carolina system. Methodist was never in the same fix, but my competitor chose to “push the envelope” a bit too far, in my opinion—so I chose to dig deeper, clarifying the difference and righting the scale, and making an unexpectedly good friend of the Methodist president in the process.

Fayetteville State was an enigma of sorts: a mid-size public HBCU (historically black college and university) from the Reconstruction era with minor but perennial bookkeeping problems, and neither warm to journalistic inquiries nor particularly responsive to any criticism. (The FSU chancellor would surely have done well to cultivate the media on those issues, but stubbornly chose not to.) Still, it hosted a marvelous public speakers program, attracting national figures such as Congressmen Andrew Young and John Conyers, as well as civil rights leader Ralph David Abernathy to the campus—at least three of the charismatic speakers I got to cover!

One of my favorite, longish Sunday features chronicled the issues and complicated reception facing white students at the overwhelmingly African American campus (titled, imaginatively, as “White Student on a Black Campus,” as I recall). One of five HBCU’s in the consolidated UNC system—others were in Durham, Elizabeth City, Greensboro, and Winston-Salem—FSU was by far the oldest, founded in the late 1860s as a semi-private “normal” school for Black schoolteachers by the Freedmen’s Bureau, before becoming a public college. It had only recently begun recruiting non-Black students on a serious basis, and now offered master’s-level programs.

Most of those who arrived now—at least the handful I interviewed—were enthusiastic about the opportunity to attend a local, low-cost public campus, but prudently guarded about their reservations. Most state public schools had been racially integrated for a decade or less in the early 1970s, so it was a new experience for students of both races, and still something of a social experiment, even in a military town.

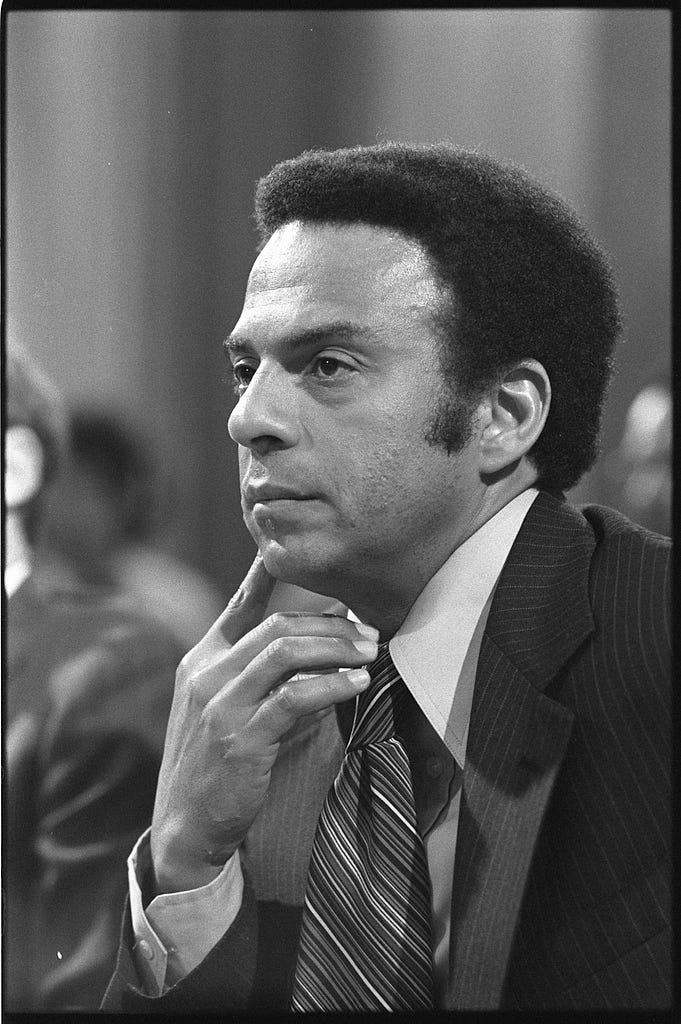

Then-Congressman Andrew Young of Georgia, who visited Fayetteville in 1974. Courtesy New Georgia Encyclopedia

Then-Congressman John Conyers of Michigan, who also spoke at FSU in 1974. Courtesy Detroit Free Press

Southern Christian Leadership Conference activist Ralph David Abernathy, also an FSU speaker. Photo courtesy Britannica.com

I had a great time listening to and chronicling those speeches. And of course, all of us shared the inevitable overflow from other portfolios—especially Pat Reese’s crime reporting, George Frink’s municipal political affairs coverage, Beth Obenshain Geimer’s Jill-of-all trades grouping, Leigh Ridenour’s fascinating features, Gene Wang’s excellent state political reporting, plus whatever else city editor David Prather needed done. Managing editor Bob Wilson was a wonderful role model—two marvelous editors in a row for me!—and kept us both motivated and occasionally, in check. We had an editorial page editor, Charley Clay; society editor, Frances Hasty; a large sports staff, led by Howard Ward and Thad Mumau; an entertainment editor, Nancy Cain Schmitt; religious editor, Jim Pharr; even a staff artist, Millie Clement; and a marvelous photography staff, led by Bill Shaw. I was fond of the whole team and worked well with all of them.

State historic marker outside the Hay Street building in 1974. Courtesy Fayettevilleobserver.com

The Fayetteville Observer, oldest N.C. newspaper, published daily since 1896. Front page from March 1865. Courtesy Wikipedia

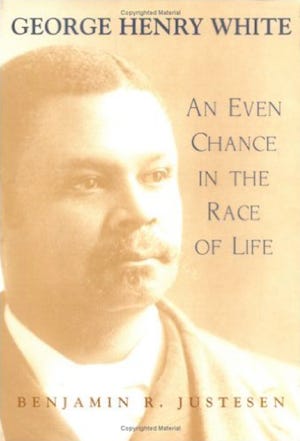

In my minor assignments, I also stumbled across an obscure historical figure named George Henry White, the Black Republican congressman from nearby Bladen County (in our circulation area) who had served North Carolina’s Second District (Edgecombe County area) from 1897 to 1901. The nation’s last Black member for nearly 30 years, White surfaced in a press release from the state history museum in Raleigh, part of a civil rights exhibit on Reconstruction-era Black officeholders. I did not realize it then, but the article I researched for the Observer would guide me, metaphorically, for the rest of my life—and become the subject of my first book.

Cover of my 2001 biography of George Henry White, published by LSU Press. Public domain photo

I also gradually got assigned to cover a few Raleigh stories, including on the State Board of Education, which set policy for the state, including our local schools. That was where I became reacquainted with Lt. Governor Jim Hunt, a board member—and later, four-term Democratic governor; and met the board’s well-entrenched chairman, Dallas Herring; and his nemesis, State Superintendent of Public Instruction A. Craig Phillips.

The venerable paper itself was a family-owned affair, run by the well-regarded Wilson-Lilly clan, including then-publisher Ramon Yarborough and his mother-in-law, a formidable but always gracious businesswoman. (Far-sighted Fayetteville also boasted a female mayor, Beth Finch!) The newspaper was still located near the AMTRAK railroad station, on a block of downtown’s notorious Hay Street—home then to a succession of topless bars, taverns, pawn shops, and other low-rent establishments catering mostly to soldiers from the base. And a magnet for the inevitable ladies of the evening, who hung out around the Observer’s rear door, near our parking lot, and for fun, occasionally chased each other with cigarette lighters, turned up to high flame levels, when other business was slow. We watched them from our rear stairwell windows …

The newspaper soon moved operations into a more modern building in an adjacent industrial area; that end of Hay Street itself has long since been razed and revitalized. The Times faded away, folded first into weekend editions, then into a morning version of the Observer. The paper has since left the family, sold off to a larger chain (Gatewood, now part of Gannett), and is still around, if now a thinner shadow of its former glory days.

I miss those vanished old days, where the seedy atmosphere of Hay Street and an air of just-below-the-surface danger reminded us of all-too-real life just a few steps away from our comfortable middle-class existence.

* * * * * *

It was a lot to keep up with, but I enjoyed it immensely, despite logistical difficulties—not limited to my inability to type stories on an IBM Selectric, or my crazy commuting-on-weekends situation—and tried desperately to learn to touch-type at a night course at FTI, when I was not searching for feature stories there. (An existential crisis—I gave up after falling asleep too much, should have tried hypnosis.) I had grown up hunting-and-pecking on R.C. Allen manual typewriters, and this transition was particularly maddening for me. (I still watch my laptop keyboard as I type—I am reasonably fast, but still transpose letters— “teh” for “the,” and the like—and depend way too much on spell-check … Still, I have managed to write seven books that way …)

The busy, state-run FTI campus catered mostly to adults seeking trade certifications, but also drew in students interested in transferring to four-year colleges. It was located on a former exclave of Fort Bragg in a quiet residential area, bordering busy commercial Bragg Boulevard, along which Daddy’s retail office supply firm sat, connecting city and reservation—long since rededicated to city schools and the like. Fayetteville would eventually annex much of the huge military reservation, vastly expanding its geographic area by nearly 30 square miles and its population base by about 30,000 people; Spring Lake, where Daddy’s second store was located, would also gain 5,000 residents and much land.

My limits were regularly challenged, but I was growing in skill, and I finally felt like a real, honest-to-goodness journalist—a childhood dream—reinforced by the fact that after three years in the profession, I was actually earning more than $10,000 a year. (Wow!!) Helen and I soon sold our Whiteville house and bought a brand-new suburban residence in College Downs, a subdivision out near Methodist College. By now, she had been hired to a new job in the Fayetteville city system, working with special needs students—in which discipline she soon went on to get a master’s degree at Chapel Hill.

But my expectations of becoming a lifelong journalist and moving on, to the big city, were about to take an unexpected detour.

* * * * * *

All was going along well until the fall of 1975, when Daddy had a second, more serious heart attack—and for a while, it looked as if he might not return to work. We all knew—Mother, sister Beth, brother Wayne, and I—that the business could not survive without his firm hand at the helm. No one on his small staff was capable of assuming the responsibility—so I suddenly faced another life-altering conundrum: whether to stay in journalism, which I loved, and watch his life’s achievement vanish, or take an indefinite period of time off and try to hold it together.

The trouble was, I had so few real business skills—I had run a second store for him one summer, and kept the doors open for him while he took the family to Europe—but despite many changes of major at UNC, had not a single practical business course to my name—and little else to offer except proximity, determination, and loyalty. And a lot of love.

Daddy had been in the process of selling off his long-held Sweda cash register franchise (sales and repairs) to his service manager and a third man, which I was somehow able to salvage with him still in hospital. Thereafter, we concentrated almost exclusively on the retail half of the office supply business—which, until Staples cut us off at the knees, was actually still profitable. I was nowhere near the natural businessman Daddy was—but somehow channeled his congeniality, Type A drive, and practical skills, learning his bookkeeping system and keeping the bills paid, the doors open, while sweeping floors, paying taxes, pleasing old customers while trying to expand our product lines to meet walk-in trade preferences.

It was a struggle, at first, but it worked. The store stayed open. Daddy did come back to work, months later, if now on a restricted schedule, with Mother driving him most days. He was generally content to let me run the place with a little oversight, as vice president and general manager of the family-held corporation. He had once warned me not to do it—he was certain I had a better life ahead of me, out there, somewhere else—but I felt an irresistible obligation to take up the burden, for a couple of years, anyway. I was sure could always go back to journalism, eventually.

I was wrong. Quickly, too quickly, two reasonably prosperous years turned into 3, and 4, and then 5 … Helen and I traded up to a newer, larger house nearby, our daughter Rika was born, we started going to a large old Episcopal Church downtown, St. John’s, in a pew near my former boss, Mrs. Lilly. Life got more and more comfortable, predictable, while something inside me felt strangely empty ….

You can guess by now, of course, that I never went back to the Observer—despite one half-hearted effort, out of obeisance to my old Peter Pan self, before realizing how much of a pay cut I would have to take. So I was trapped …

I look back on those early years now and miss them, with a surprising degree of remembered pain. When I was a journalist, I was hungry sometimes, and often frustrated, but actually felt as if I were doing something useful—every time I saw my name over one of those stories I had slaved over—for society at large, as well as for my inner self. I don’t think I was kidding myself, either … Even today, I watch print journalism fading away, swamped by the shallow ego-centric antics of celebrity anchors on TV who talk too fast and cannot pronounce half the words on their teleprompters (and seem baffled by them), betraying a disturbing lack of depth and preparation. All insincerity, glitz, with overly emphatic, one-sided opinions and precious little substance. In short, Ted Baxter clones … with no redeeming comedy …

Two years as an overworked print reporter and most of them would have been washed out forever … and good riddance, I say!

* * * * * *

All that is gone now, half a century later. It faded behind me when I finally decided to leave Fayetteville, and go back to graduate school full-time—after pursuing a part-time master’s degree in adult education and political science, first out at Fort Bragg’s FSU-N.C. State campus, then finishing by commuting to Raleigh once or twice a week. I now wanted to become a professor of journalism—not an active journalist, if I still dabbled occasionally as a free-lancer. Because on this stage, I simply felt as if I were suffocating. But it was a risky gamble to take—and one I lost, badly.

My first marriage soon collapsed and failed under the stress of my decision; Helen and I managed to part ways amicably, if painfully, and remain good friends today. Mother and Daddy soon sold the business; Daddy retired early on disability, dying soon afterward.

By then, I had left graduate school midway through, to become a diplomat, and traveled the world for the Department of State for more than a decade. In a very real sense, I re-booted myself (not for the last time). I saw Jamaica, Denmark, Suriname, Singapore, Latvia, and nearby countries. I learned Russian and Danish. I married again, this time, more happily.

I now have three grandchildren by Rika, all of whom I treasure. I did finally go back and finish graduate school (Ph.D. in interdisciplinary studies), have written many books, worked as a nonprofit administrator, even taught in high school and college for a while. I have lived all my subsequent lives fully, and productively—yet they were all such different lives, far away from the profession I was so sure I would die practicing …

But all of those first four years linger now, just outside my line of vision, in the canyons of my mind: living memories of a younger me, more audacious and daring, like something echoing the last line and chorus from a favorite ballad of mine by the fine British-Welsh singer Mary Hopkin (1969):

Oh my friend, we’re older but no wiser, for in our hearts the dreams are still the same …

Those were the days, my friend, we thought they’d never end. We’d sing and dance, forever and a day. We’d live the life we choose, we’d fight and never lose, for we were young and sure to have our way …

Next time: To the stars … and time for a break to recharge the batteries …

I'm just catching up on this set of posts now and enjoyed reading about your early days as a reporter.