Remembering a cub reporter’s days in the newspaper game

Part 1: Life on the beach: Sea turtles, stranded tourists, and female mayors

The advent of the New Year has sent me back in time to my early days as a newspaperman, just out of college, and my first attempts at covering local news for weekly and bi-weekly newspapers in two of North Carolina’s southeastern counties. Brunswick and Columbus.

In the late spring of 1971, I was a senior at UNC-Chapel Hill, taking a few journalism classes to fill out electives in my English literature major, when Eddie Sweatt, a publisher from Cheraw, South Carolina, visited the editorial writing class taught by the venerable Walter Spearman. He was in search of a summer editor for his regional chain’s little weekly paper in Shallotte, a near-seaside village of 500 permanent residents, one of two papers in Brunswick County. It was a regional commercial village on a main north-south highway, U.S. 17, a few miles north of the South Carolina line.

The masthead of my first newspaper job, in Shallotte, N.C. Public domain photo

I had changed my major several times over four years at Chapel Hill, finally returning to English; a victim of atrociously careless planning, I needed to come back for one more semester in the fall to graduate. While I still wasn’t sure what I wanted to be when I grew up, journalism looked like a place to start—either that or I would have to become a schoolteacher for a while, at least. (The two lowest-paying professions available always had plenty of vacancies!)

And even if The Brunswick Beacon was not where I had planned to end up—too small by far; I still fancied myself writing for the New York Times when I finished school—I soon learned that life is what happens when you’re busy making other plans.

In any event, a summer job—either in Chapel Hill or my hometown of Dunn, if I was to pay for gas, food, and a place to live—was a necessity while I waited to come back. So when Walter recommended me to Eddie as a promising writer, I jumped at the chance to live at the beach and get some valuable summer work experience on my resume.

So while all my friends were busy mulling permanent job offers, getting married, or making plans for graduate school—sometimes, all three at once—I packed up my 1969 Cougar and headed for the end of the earth—for me, the Atlantic Ocean—and a step back in time.

Map of North Carolina’s southernmost county, Brunswick, showing its towns. Map courtesy Wikipedia

Brunswick County was a sprawling rural, poor county, founded in 1764, covering about 900 square miles with just over 50,000 residents in 1971. Most of the county’s economy relied either on fishing, agriculture, or summer tourists at the half-dozen beaches—all located on barrier reef islands, requiring drawbridges across the Depression-era Intracoastal Waterway—although a few industries, including a new nuclear power plant, had begun making inroads in recent years.

The county seat, Southport, at one end of the county, was the largest town, with about 2,000 people and despite the 907 square miles, the county’s only stoplight at the time (I kid you not). Once a major seaport, located at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, it dated back to the 1790s, just after the end of the Revolutionary War. Many of the grand old houses left along seafront Bay Street faced east toward England, a silent tribute to the affection many of its residents still felt for the ancestral monarchy.

Part of that historical nostalgia was reflected in the very accents of longtime residents, who used such quaint (to me, anyway) expressions as “Let me hope you do that” (or “help”), and still routinely employed such quirky pronunciations as “hoigh toide” (high tide) in their speech. It reflected the Elizabethan era of their long-dead ancestors, who had actually founded many of the original towns and rice plantations centuries earlier. The ruins of the royal colony’s original capital, Brunswick Town, long since abandoned after being razed by British troops in 1776, were still a popular tourist destination, along with nearby Orton Plantation, built in 1735.

But most tourists came primarily for the lovely sandy beaches—along the adjacent islands off the county’s southern coastline, west of Southport—Sunset, Ocean Isle, and Holden, and the three Oak Island communities of Long, Yaupon, and Caswell, plus the still-developing luxury island of Bald Head across from Southport—with the county’s population often doubling during the summer months. To top it off, the tiny village of Calabash attracted hordes of hungry tourists to its 20-plus fried seafood restaurants, among the busiest in the state.

I was lucky enough to be offered rental accommodations of a small, cramped house trailer with a spare bedroom on the beach at Holden Beach—at $100 a month, which I could just about afford on my tiny salary of $110 a week. (That was a little above minimum wage at the time. but easily the most money I had ever made!)

All in all, it was heaven to me—I loved the beach, and could actually jump into the ocean, a few feet away through the dunes—and ended up having quite a few visitors during my three months there. The work was enough of a challenge that I never got bored—although I was not the world’s most enterprising reporter, preferring to write only a few stories and keeping the editorial page alive to actually attending municipal or county meetings and beating the bushes for interesting features.

Now I was not a perfect fit for the job, which turned out to require a sensible set of organizational skills I had not yet developed—placing regular calls to existing sources, cultivating new ones, and coming up with interesting local angles on statewide and national events. I had not taken enough J-school courses at Chapel Hill—no editing courses at all—and worse, I had never worked as a reporter before. My publisher, Kelvin—a skillful photographer and smart businessman—had little newspaper experience before he was hired by Eddie to take over the small weekly; he was better at selling ads and laying out pages than anything else.

The Beacon had a small staff—a more-or-less full-time typesetter/offset layout composer and one reporter and feature-writer, plus a teenage “gopher” for odd jobs. Most of our weekly paper consisted of columns written by local residents—skilled at inserting every citizen’s name into their products—combined with obituaries, high-school sports, wire-service reprints and letters to the editor, of course. The circulation was roughly 2,500, mostly mailed out—we had an manual addressograph machine which printed the mailing addresses onto a corner of the front page—and Kelvin offered to pay me an extra $15 a week to perform that task on Wednesday afternoons, which I was happy enough to do (otherwise, I worked 4 1/2 days a week), and it was easy to learn).

We did not actually print the newspaper, but once a week, took the finished photo-offset page negatives over to a larger regional newspaper, the News Reporter in Whiteville, about 50 miles away, and brought the bundles of printed copies back for addressing. Maybe 10 or 20 percent of the weekly print run went to local stores for sale, or newspaper distribution boxes—the kind you put a quarter into to release the paper—on the street.

So what kind of news made it into the Beacon? High school graduations, business news, civic club meetings, traffic accidents—the usual stuff for small towns—and a lot of it was political news, always controversial, especially here. Traditionally a Democratic stronghold, like most of the Tar Heel state, Brunswick County had recently begun to turn the political page back to electing Republican county officials for the first time since the late 19th century—a precursor of the sea change that would swamp the whole state in 1972 and later years.

But one of the more interesting things to me was how many of the small towns were accustomed to electing (nonpartisan) female mayors, including Southport itself, where businesswoman Dorothy Robinson Gilbert (1912-1994) was perennially popular, and as I remember, in at least two of the smaller beaches (Winifred Wood at Sunset and Virginia Williamson at Ocean Isle).

The town of Holden Beach, N.C., viewed from the Intracoastal Waterway side. Photo courtesy NCBrunswick.com

Another prominent woman in Brunswick County was Margaret Taylor Harper (1917-2009), a successful businesswomen and journalist who ran twice for lieutenant governor as a Democrat—and while she did not win either year’s primary, still emerged as one of the state’s most influential party members. The family’s weekly newspaper was the State Port Pilot, our cross-county competitor; she had edited it in her husband Jim’s absence during World War II, and still kept her hands-on approach.

“The best thing I ever did was to lose,” Margaret said later. “Back in the ‘60s, as a woman, they wouldn’t have let me do anything if I had won. Instead of winning, I went on and was on various boards and commissions, which probably was a bunch more helpful than anything I would have done as lieutenant governor.”

A graduate of Greensboro College, she served as secretary-treasurer of the North Carolina Press Association and president of the North Carolina Press Women and North Carolina Federation of Women’s Clubs. During her two terms on the UNC-Chapel HIll Board of Trustees, she chaired several committees.

I was fascinated by this abundance of women in local politics—women had rarely been so active politically in North Carolina, although Raleigh, the state capital, was soon to elect a woman, Isabella Cannon, as mayor. More women were running every two years for the state’s General Assembly in both parties every year. (It was in the days just before the Equal Right Amendment passed Congress, and I was already an avid promoter of equal rights for women.)

It would be another 30 years before North Carolina elected its first female lieutenant governor, Beverly Perdue—later elected governor in her own right—and two female U.S. senators, but Margaret Harper set the early standard, I always thought.

Southport as it appears today, gentrified but still charming. Photo courtesy https://www.facebook.com/cityofsouthportnc

* * * * * *

Two of my favorite early stories still linger in my memory half a century later. One was a weeks-running story involving a dead sea turtle found on the sand at Holden Beach, not far from my trailer and apparently shot to death by an illegal poacher. Sad enough that such an amazing creature had to die—I had come across a couple of females laying their eggs on evening runs, and they were a lot faster than I was, as it turned out. But the town fathers decided initially to let the carcass rot in the summer sun, rather than pay to have it hauled away and buried.

Granted, it was heavy—300 to 400 pounds—but the smell was quickly overwhelming. In the middle of tourist season! So I wrote about it, if a bit impertinently, on the front page, and I probably risked being tarred and feathered for innocently suggesting the town was shirking its civic responsibilities. Grumbling, they got around to its removal and burial elsewhere before the followup story appeared.

Another memorable story that summer was less deadly—almost comical, if it hadn’t been so freakish. Oak Island was connected to the mainland back then by exactly one drawbridge—an old-fashioned, center-mounted “swing” bridge, across the Intracoastal Waterway, dating from the late 1930s—and the only other way off the island was by boat or to swim. (At low tide, you could sometimes walk to the next island over, Holden Beach.) Large barges went up and down the waterway in both directions, usually to and from Wilmington, the nearest city of any size.

The 1930s-era “swing bridge” over the Intracoastal Waterway at Oak Island, NC, before its replacement. Public domain photo

Early one morning, at 1 a.m., the barge and tug operator apparently dozed off at the wheel, and instead of heading down the preferred wider “lane” beside the bridge as it was turned, let the barge drift down a narrower channel, where it met unexpected resistance from the rest of the bridge—and knocked it off, unceremoniously, into the waterway. So much for NC Highway 133 …

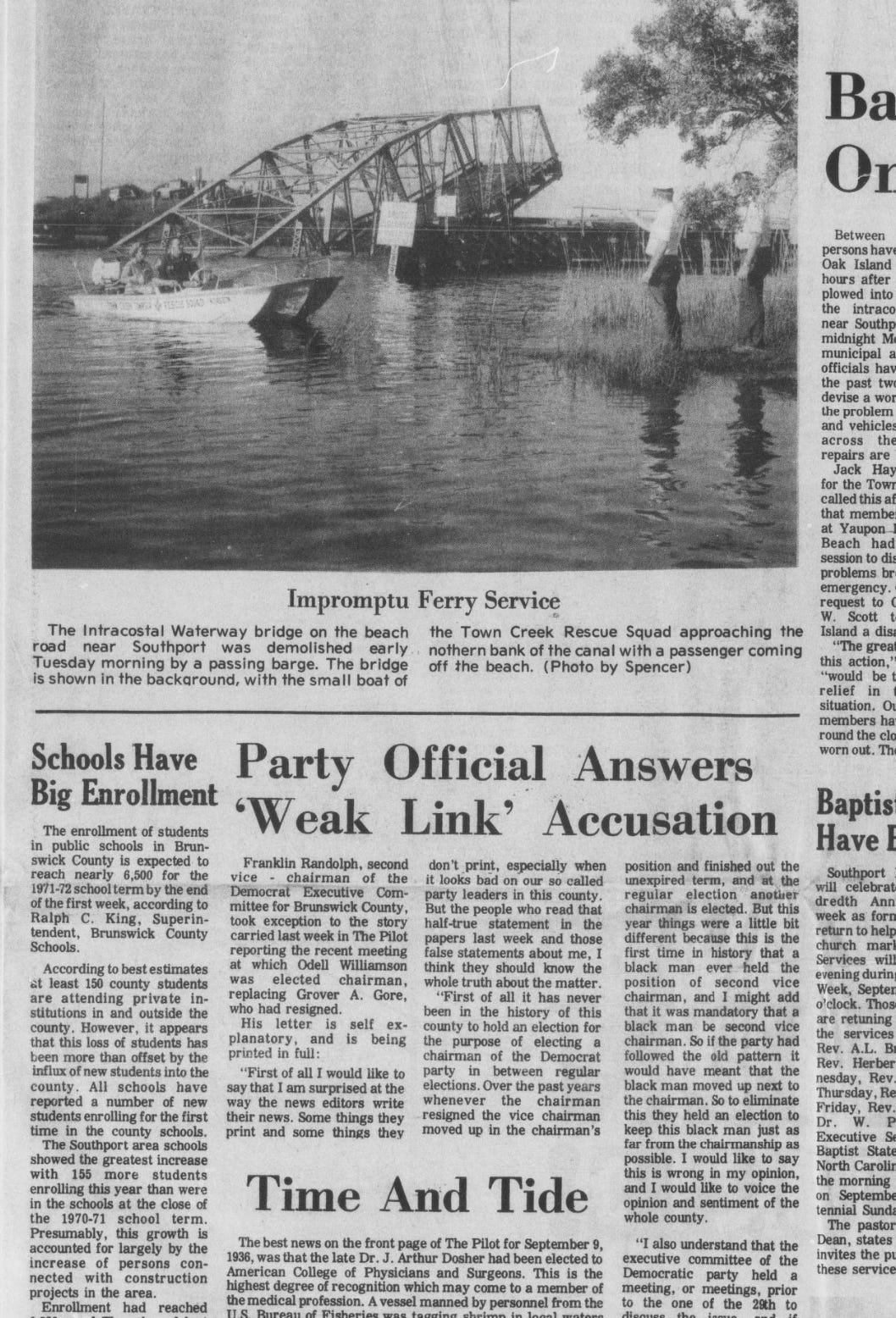

Damaged bridge pictured on front page of the Southport newspaper from September 8, 1971. Photo courtesy State Port Pilot

A handful of cars were waiting patiently for the barge to pass so they could depart the island. As one mystified driver assured me, “I will never watch Johnny Carson again. That’s why I was so late leaving.” It was Labor Day weekend, and he was among about 4,000 happy out-of-town tourists still soaking up the last of the summer sun that week. Suddenly, they were stranded … within a day or two, all the stores on the island started running out of food and the gasoline stations out of fuel.

The state quickly rerouted the Southport-Fort Fisher automobile ferry—which usually connected Southport with New Hanover County’s Pleasure Island to the north—into emergency action, using a Coast Guard ferry slip on Oak Island to connect with the normal landing-launching slip just north of town. But it could only transport 30 to 40 cars at a time, making the evacuation process painfully slow before the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was able to construct a temporary pontoon bridge.

More than three years later, the bridge was finally replaced with a high-rise bridge, ending the danger from another out-of-bounds barge. (Today there is a second high-rise state bridge to the west.)

Most of the passengers I interviewed on an early ferry ride were matter-of-fact, even joking about the unexpected delay in their departure. At least it wasn’t a hurricane, one said. And if you have to be stranded somewhere, there are worse places than the beach … until you run out of beer, anyway … The ferry rides that day were like a rolling end-of-summer party!

As my original summer job came to an end, two momentous events occurred: I decided to move off the beach into a rental house at Shallotte Point, nearer the office—after an August hurricane narrowly missed Holden Beach—just after my boss, Kelvin, decided to offer me the summer job full-time, if I wanted it. Yes! I temporarily gave up my early plans to return to school that fall and decided to stay on until the winds took me elsewhere.

Which, as it turned out, wasn’t all that long.

Next time: A winter vacation, a new dog, and a new job …

I enjoyed reading this post and learning of your early days as a reporter. And as always, you tell the tale well.