More than 300 African American postmasters appointed during the 19th century

Part 2: African American women gain a strong foothold in the 1890s

In my last post, I recounted the appointments of African American postmasters after the end of the Civil War to 1900, during the administrations of presidents from Andrew Johnson to William McKinley. More than 300 appointments—mostly of men of voting age—were made during those three decades, covering both tiny villages and large cities, and mostly in the Southern states of the old Confederacy, where more than 80 percent of black Americans still lived at the time. Although a small percentage of the nation’s total number of postmasters—perhaps 80,000?—it still symbolized the importance of extending the advantages and responsibilities to this newest large group of American citizens.

In today’s post, I will explore the smaller group of black women who became postmasters on the late 19th century. The most famous of these early women is probably Minnie Geddings Cox of Indianola, Mississippi, who served her local post office for about a decade, but she was neither the first nor the longest-serving of the 26 women revealed in my research. I wrote about some of these postmasters—most of whom were named by Rep. George H. White for small rural offices in his “Black Second” district between 1897 and 1901 and appointed by President William McKinley—in my 2001 book, George Henry White: An Even Chance in the Race of Life (LSU Press) and in my recent book, Forgotten Legacy: William McKinley, George Henry White, and the Struggle for Black Equality (LSU Press, 2020).

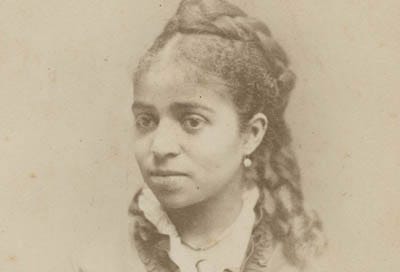

Minnie Geddings Cox (1869-1933), twice postmaster of Indianola,

Mississippi, between 1891 and 1903. Public domain photo

Mrs. Cox was a Fisk University graduate and trained schoolteacher, when she was first appointed Indianola’s postmaster by President Benjamin Harrison in 1891, at age 22, to fulfill an unexpired term, she served at Indianola until 1893. In 1897, she was reappointed by President McKinley, and remained a popular figure in the county seat until she was forced to flee in late 1902 and move away, temporarily, after threats were made against her life by white supremacists—perhaps because of the comparatively large salary she received ($1,100 per year). President Theodore Roosevelt at first refused to accept her resignation, then angrily closed the post office indefinitely after she fled; he later grudgingly reopened the post office when informed every county seat was required by federal law to have regular mail service.

You can read more about her life on the Smithsonian Institute’s website for the National Postal Museum: https://postalmuseum.si.edu/research-articles/the-history-and-experience-of-african-americans-in-america%E2%80%99s-postal-service/minnie.

Unlike Mrs. Cox’s well-funded third-class post office, most of the offices staffed by female postmasters offered comparatively low compensation—sometimes the smallest postmasters received no salary, earning only the amount of postage sold—but it conferred the rarest of distinctions on the appointee, as a community leader of some distinction, often the only employee of the federal government that the majority of U.S. citizens ever met personally on a regular basis. It required no special training beyond the simple ability to read and write. Political involvement, however, was often a requisite in the partisan patronage system; the majority of postmasters at any given time were chosen by state leaders of the party in power nationally, and all male postmasters were expected to be faithful members of that party. Females, of course, could not (yet) vote—but were identified in the public eye with the party, nonetheless.

Although precise numbers are not available, women had been appointed under the Constitution, sporadically at least, since 1792, when Sarah Decrow was recorded as in charge of the post office in Hertford, North Carolina, and became increasingly common in the late 19th century, particularly during the Civil War, when fewer men were available. Some widows were named to replace their husbands, having already assisted them as clerks or even formal assistants, and continued to run their offices for many years. By the 1870s, white women had begun to serve more widely, without incident, although only married women were generally able to gain the necessary bonds.

During his first term, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed John A. J. Creswell, a former Maryland Senator, as his first Postmaster General. A longtime abolitionist, Creswell enthusiastically integrated the Post Office Department’s workforce, and by late 1872, had begun to appoint the first of his three African American female postmasters. The first was Mrs. Anna M. Dumas, who became postmaster of predominantly-white Covington, Louisiana, the parish seat of St. Tammany Parish, near New Orleans, in November 1872. Mrs. Dumas proved to be a congenial choice, well accepted in her small community; she served for more than a dozen years, until she was replaced in June 1885.

A month after Mrs. Dumas was chosen, Creswell selected Mrs. Mary S. Middleton as postmaster of Midway, South Carolina, succeeding her husband, Benjamin W. Middleton, who had resigned after two years on the job. Mrs. Middleton remained postmaster until August 30, 1875. In July 1873, he selected Mrs. Eliza H. Davis as postmaster of Summerville, South Carolina, which she served for the next 11 years, until September 10, 1884.

* * * * * *

After Creswell’s resignation in 1874, Mrs. Davis was the last African American woman appointed as postmaster until the presidency of Benjamin Harrison, who took office in March 1889. Appointments of black postmasters had fallen to a new low under Democrat Grover Cleveland, with only four (all men) named in four years—after ten times that many under Garfield and Arthur. Prompted by requests from the nation’s only African American congressman—freshman Rep. Henry P. Cheatham of North Carolina—Harrison began appointing black postmasters at a record pace—more than 100 by the end of his term, as many as all previous presidents together. Seven black women joined the ranks in four states—Florida, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina—including Mts. Cox at Indianola in 1891.

Others named by Harrison included two African American women from Cheatham’s “Black Second” district: Mrs. Cora E. Davis, named to the county seat’s post office at Halifax Court House in April 1889, weeks after Harrison was sworn in, and Sylvia Drake, who was nominated for the post at Rocky Mount in March 1890, but never took office, reportedly unable to post the required bond. [She was, however, followed into office by two black men, Weeks Armstrong, who was removed from office in 1890, and William Lee Person, who completed the term in 1893.]

The most controversial of the female postmasters, however, was Mrs. Davis. She was reportedly popular with most residents, and drew compliments from local officials in Halifax, but after less than two years on the job, was nonetheless removed from office for charges of alleged embezzlement, which some local citizens dismissed as spurious. She was quickly replaced by a black man, Jonathan Hannon, a former register of deeds, who completed her term without incident.

In addition to Mrs. Cox, five more women were appointed by Harrison over the remainder of his term: Harriet “Hattie” Commander of Chesterfield, South Carolina (1889-1893); Mrs. Fannie A. James in Jewell, Florida (1889), who served until 1903; Mrs. Mary Ann Aldridge Baker, who filled an unexpired term at Dudley, North Carolina, from 1891 to 1893; Martha E. Middleton in Kenansville, North Carolina, who filled an unexpired term from 1892 to 1893; and Mrs. Frances J. M. Sperry, who served as postmaster at Georgetown, South Carolina, from 1890 until 1893.

During his second term, President Grover Cleveland appointed his first and only African American female postmaster in May 1895: Mary Virginia Montgomery of Mound Bayou, Mississippi, an all-black town founded by her father, legendary Republican party leader Isaiah Thornton Montgomery, and held that post for the next seven years until her death in 1902.

Soon after beginning his first term in March 1897, President William McKinley began appointing a flurry of African American postmasters—more than 100 over the years of his first term—and was ably assisted by Rep. George Henry White of North Carolina, the nation’s only black congressman. White provided the President with at least three dozen black nominees. They included seven black women: Mrs. Mary Ann Baker, reappointed at Dudley; Alice E. Burt at Ita; Mrs. Willie F. Coats at Seaboard; Ada Dickens at Lawrence; Elenora J. Newsome at Margarettsville; Emma S. Roberts at Jackson; and Emma V. Wynns at Powellsville. [Mrs. Coats was the wife of former postmaster William C. Coates, who had served Seaboard from 1889 to 1893, and who went on to serve one term in the N.C. General Assembly (1899-1900).]

The state’s eighth black female postmaster, Mary Guion, was named by McKinley to staff the Bladen County post office at Tar Heel—outside the “Black Second”—in June of 1897. The North Carolina octet of women were soon joined by five black female postmasters from other states: Mrs. Virginia E. B. Baham, named postmaster of Madisonville, Louisiana, in May 1897; Mrs. Cox at Indianola, Mississippi, also in May 1897; and Louisa C. Jones, named in September 1897 to fill the vacant post at Ridgeland, South Carolina.

Laura Reed of Edisto Island, South Carolina, was also selected to complete an unexpired term as postmaster by McKinley in April 1898. She was followed in February 1900 by Mrs. Elizabeth Smalls Bampfield [1858-1959] of Beaufort, South Carolina, who succeeded her late husband, Samuel J. Bampfield (1845-1899), who had been named to that post by McKinley in October 1897. [Mrs. Bampfield was also the daughter of venerable ex-congressman Robert Smalls, now serving as U.S. federal collector at the port of Beaufort; the mother of 12 children, she managed to hold the post for a nearly-astounding eight years!]

Elizabeth Smalls Banfield, postmaster of Beaufort, S.C., 1900-1908.

Photo courtesy Collection of Massachusetts Historical Society

In January 1898, McKinley also reappointed Mrs. Fannie James as postmaster of Jewell, Florida, a post she had held since 1889 and would continue to hold until 1903.

Several of these female postmasters failed to complete their four-year terms, for undisclosed reasons: Ada Dickens left her post at Lawrence in November 1899, after just two years, as Alice Burt also did at Ita in 1899. In addition, Emma Wynns stepped down at Powellsville in early 1898, after just six months, while Mary Guion served barely a year at Tar Heel, before departing in July 1898.

But others served for comparatively long periods. Mrs. Baham and Mrs. Jones, for instance, each served as postmaster for 12 years, stepping down in 1910, while Mrs. James served the Jewell post office for almost 14 years, before retiring in 1903. The longest serving female postmaster was Mrs. Baker, previously named by President Harrison, who served until 1911, bring her total service to 15 years at the end of her last term. She was also the widow of a former Dudley postmaster, J. Frank Baker, who had served briefly under President Arthur in the mid-1880s.

And what of Minnie Cox? After the furor subsided, Mrs. Cox and her family did return to live in Mississippi, where she became a successful private banker and businesswoman, but they chose to live outside the unwanted limelight of the 1902 events. She died in 1933.

Next time: Life in “Disneyland” of the South China Sea