More tales of North Carolina's 19th-century African American legislators

Part 3: Congressmen from the "Black Second"

I recently introduced readers to a handful of African American legislators elected to the North Carolina General Assembly during the nineteenth century, among more than 125 black state legislators, all Republicans, who held office between 1868 and 1900.

Building on my decades of research into the life of George Henry White, a future congressman who served in the 1881 and 1885 sessions, I am continuing my occasional series on North Carolina’s black public servants during the period.

Most of those legislators were well educated, often attending or graduating from historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), including Shaw University, Lincoln University of Pennsylvania, and Howard University, and became physicians, schoolteachers, ministers, and journalists. A few were self-educated, but despite a lack of formal training, still managed to rise to positions of influence and respect in the African American community.

In today’s post, I explore the lives of George Henry White’s three predecessors as congressman from the “Black Second” congressional district. I have written about them in greater length in other venues, including in my 2001 biography, George Henry White: An Even Chance in the Race of Life (LSU Press), and in my articles in the North Carolina Review of History.

Rep. John A. Hyman, 44th Congress (1875-1877)

Courtesy, National Archives & Records Administration

John Adams Hyman (1840-1891) was born to enslaved parents in Warrenton, North Carolina, on July 23, 1840. As a young man, while apprenticed as a janitor to a white jeweler, he was taught to read and write; the jeweler and his family were later forced to leave Warren County as a result of breaking the state law against educating slaves. Hyman himself was sold to a slaveholder in Alabama and was resold several times. He returned to North Carolina after the Civil War ended, and began farming; he also became active in the Republican party, served as a delegate to the party’s 1867 state convention, and was selected as a member of the GOP state executive committee.

On November 1867, Hyman was one of 15 black delegates chosen to attend the state constitutional convention of 1868, and was then elected to the state Senate from Warren County (20th District). He was one of the first three blacks to hold that post, along with Henry Eppes and Abraham Galloway. Reelected to the Senate in 1870 and 1872, Hyman unsuccessfully sought the GOP nomination for Congress in 1872 for the new “Black Second” district, predominantly black and Republican district gerrymandered by the legislature’s Democratic majority.

In 1874, Hyman, at just 34 years of age, won the party’s congressional nomination, and subsequently won what seemed to be a clear victory over Democrat George W. Blount in the November election. Blount, however, contested his loss to the full House, which finally ruled in Hyman’s favor in August 1876, just a few months before his term was set to end (March 1877), and had little to show for his time in Congress.

By that time, Hyman had also lost his bid for renomination; he briefly returned to Warren County as a farmer and businessman, before moving to Maryland, where he worked as a mail clerk’s assistant. In 1888, he unsuccessfully sought once again the “Black Second” congressional nomination, which was won by Henry P. Cheatham.

At 51 years of age, Hyman died in Washington, D.C., in September 1891. He is buried nearby in National Harmony Memorial Park Cemetery in Hyattsville, Maryland,

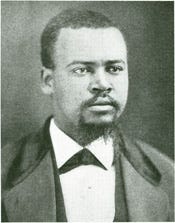

Rep. James E. O’Hara, 48th and 49th Congresses (1883-1887)

Courtesy Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University

James Edward O’Hara (1844-1905) was born on February 26, 1844, the illegitimate son of an Irish seaman and a free West Indian mother from the Danish island of St. Croix. Little is known of his childhood, except that he spent much of it in the Danish West Indies and was well educated; until adulthood, he believed he was born there, even filing a formal request for naturalization at one point. (He later rescinded the request, and thereafter claimed his mother had briefly lived in New York City at the time of his birth.) After moving back to the United States, he first visited North Carolina in 1862 during the Civil War, accompanied by Northern missionaries, and became a schoolteacher in the Union-occupied coastal city of New Bern.

After the War ended, O’Hara moved to Goldsboro, where he became active in Republican party politics. He served as a legislative clerk in the state General Assembly during its 1868-1869 session, and then moved to Washington, D.C., to work as a clerk for the U.S. Treasury Department and to study law at Howard University; while he did not graduate, he continued private studies under a white lawyer in Enfield, North Carolina, after 1873, and was soon admitted to the state bar. Elected to the Halifax County commission in 1874, he became its chairman, and twice sought the party’s nomination for Congress from the “Black Second” congressional district, heavily Republican, before succeeding in 1878.

In the 1878 general election, O’Hara was defeated in a three-way race for Congress riddled by fraud, by white Democrat W. H. “Buck” Kitchin. He contested the loss to Kitchin, but his contest was formally rejected by the House in 1880. A distinctive public figure because of his red hair, O’Hara was often plagued by scandal, both about the controversy over his place of birth—since amended to New York City—and charges of corruption as a county commissioner, for which he was tried but never convicted. Another charge of bigamy involved his failure to properly divorce his first wife, Ana Maria Harris—whom he had married in New Bern in 1864—before marrying Eleanor Elizabeth Harris in 1869. He and his second wife had at least three children.

Many observers believed his political career was over, but in 1882, at age 38, he astounded many by again winning the party’s nomination from the “Black Second” district. This time he was overwhelmingly elected to the first of two terms in the U.S. House; he was easily reelected in 1884. O’Hara was an active member of Congress between 1883 and 1887, gaining national exposure in the press by proposing an unsuccessful but controversial antidiscrimination amendment to an interstate commerce bill, which would have required equal accommodations for riders of all races on the nation’s railways.

Renominated by the party doe a third term in 1886, he was defeated in a three-way general election—including his bitter rival, independent black challenger Israel Abbott—losing to white Democrat Furnifold Simmons. In 1888, O’Hara lost his sixth and final race for the congressional nomination to Henry P. Cheatham. After leaving Congress, O’Hara briefly moved back to Enfield to practice law and publish a weekly newspaper. In 1890, he moved his law practice to New Bern, joined in it by his son Raphael, who had recently graduated from Shaw University. He died there of a stroke in 1905, and is buried in the city’s Greenwood Cemetery.

Rep. Henry P. Cheatham, 51st and 52nd Congresses (1889-1893). Public domain

Henry Plummer Cheatham (1857-1935) was born to an enslaved mother and an unnamed white father in Granville County, North Carolina, in December 1857. After being privately educated by his master, Cheatham entered the county school system after the Civil War ended, and in 1876, entered Raleigh’s Shaw University, where he received a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree in the early 1880s. Although trained as a lawyer, he chose instead to become an educator, serving as a public schoolteacher and then, briefly, as principal of the normal school for black schoolteachers at Plymouth, North Carolina, before entering politics in 1884.

After receiving the Republican nomination for register of deeds for the newly-created Vance County, Cheatham was elected to that post in November 1884, and moved to the new county seat in Henderson. In 1888, he was nominated by “Black Second” Republicans as their standard-bearer for Congress, defeating former congressman James O’Hara in his sixth and final campaign for that office. Just 30 years old, Cheatham narrowly defeated the white incumbent Democrat, Furnifold Simmons, in the November election, weeks after independent black challenger George A. Mebane withdrew from the rac.

In December 1899, he took office in Washington, D.C., as the nation’s only black Congressman when the 51st Congress opened. He was later joined briefly in 1890 by Virginia’s John Mercer Langston and South Carolina’s Thomas E. Miller, whom the Republican-majority House seated over white Democratic opponents.

Cheatham then defeated an independent challenger on 1890 to win a second term, after the official Democratic nominee withdrew for reasons of ill health. In the 52nd Congress, Cheatham was the nation’s only black representative. He gave only a few speeches during his congressional career and sponsored several unsuccessful bills, but during his first term, did successfully propose the appointments of nearly a dozen black postmasters by President Benjamin Harrison in the “Black Second.”

After being renominated for Congress in 1892, he was selected as a statewide delegate to that year’s GOP national convention in Minneapolis, and voted to renominate President Harrison. But Cheatham’s reelection campaign was hobbled by the actions of Democratic legislators, who had reconfigured the “Black Second”—subtracting two reliably Republican counties, including Vance, and adding a heavily-Democratic county in redistricting the state based on the 1890 census—in what became a successful effort to defeat him. In order to run for reelection, Cheatham himself was forced to move his family’s residence from Henderson to Littleton in Warren County; in the Democratic sweep that fall, with many of his votes disallowed, he was decisively defeated by white Democrat Frederick A. Woodard.

Despite overwhelming obstacles, Cheatham persisted in efforts to return to Congress, claiming his fourth straight GOP nomination in 1894—although it required last-minute intervention by the Republican national committee to mediate the stalemate between Cheatham and his brother-in-law, district solicitor George Henry White of Tarboro. Cheatham angrily blamed his defeat by Woodard in the 1894 election on White, who refused to campaign for him, and the family feud extended well into 1896, when White finally won the “Black Second” nomination outright and prevailed in the general election.

In the spring of 1897, Cheatham was appointed by President William McKinley as the Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia, one of the four highest federal posts reserved for black appointees. He remained in that position until January 1902, when he was replaced by President Theodore Roosevelt, He returned to North Carolina, where he became superintendent of the state’s black orphanage at Oxford, a post he continued to hold until his death in 1935.

Cheatham and his first wife, Louisa Cherry Cheatham, had three children before her death in Washington in 1899. He and his second wife, Laura Joyner Cheatham, whom he married in 1901, had two more children. He is buried in Oxford’s Harrisburg Cemetery.

Next time: More than 300 African American postmasters appointed in the 19th century