More tales of North Carolina's 19th-century African American legislators

Part 3: The longest to serve, four or more terms

I have previously introduced readers to a handful of African American legislators elected to the North Carolina General Assembly during the nineteenth century, among more than 125 black state legislators, all Republicans, who held office between 1868 and 1900.

This week, I continue my occasional series on North Carolina’s black public servants during the period, many of whom I have written about in previous articles for the North Carolina Historical Review and in other publications. Today’s post explores the lives of a group of legislators who served for at least four elected terms:

Willis Bunn (1840-1899?) was born around 1840/1843, probably in Edgecombe County. Little is known about his youth or early education. A freed slave, he served after the Civil War as both a magistrate and justice of the peace (1873) in Edgecombe County. A farmer by trade, he owned $250 worth of personal property in 1870, according to that year’s U.S. census.

He served four consecutive terms in the N.C. House of Representatives from Edgecombe County as a Republican, elected in 1870, 1872, 1874, and 1876. He served in the 1870, 1873m 1875, and 1877 sessions of the General Assembly, when his committee assignments included (1869-1870) Privileges and Elections; (1870–1871) Engrossed Bills, and Penal Institutions; (1874) Education.

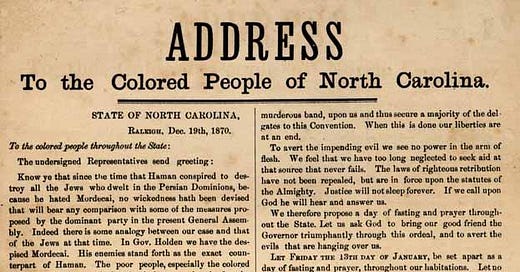

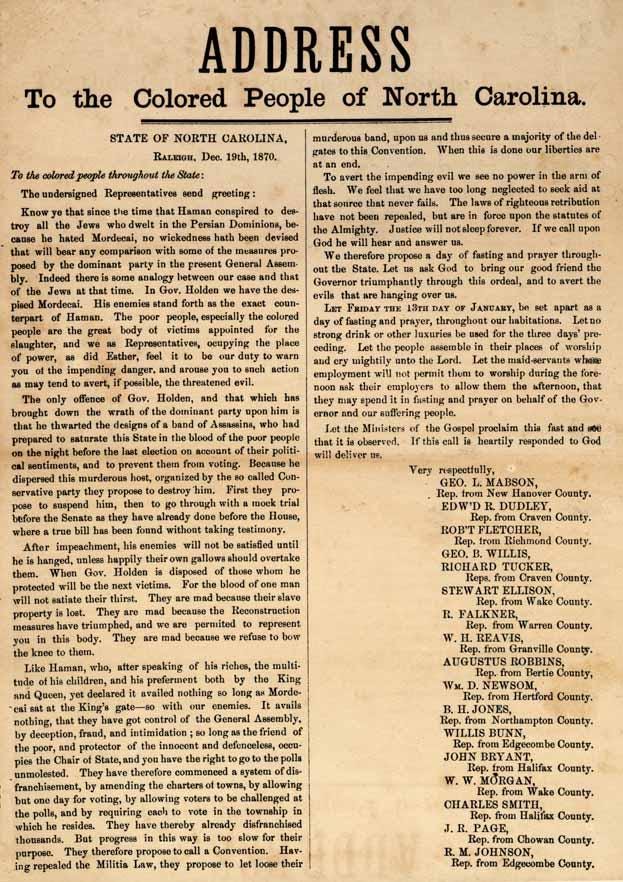

He was among 17 black legislators signing an “Address to the Colored People of North Carolina,” published on December 19, 1870, and calling for a statewide day of prayer and fasting in January 1871 to protest the impeachment of Republican Governor William W. Holden.

Among Bunn’s notable legislative actions was an unsuccessful bill which attempted to amend State law to prevent young black women from being apprenticed to white masters. In 1871, he and fellow Republican Richard Johnson vigorously lobbied in favor of holding a referendum on a controversial proposal to change the boundary line between Edgecombe and Nash Counties, but their efforts were unsuccessful. Bunn also offered a formal protest, signed by him and eight other black legislators, against the enactment of the so-called “Amnesty Bill” passed by the House in November 1874.

Bunn held no elected office after 1877, although he is believed to have been an unsuccessful Republican candidate for constable in Edgecombe County in 1896.

Bunn appears to have been married twice. His first wife, Cora, had one daughter, Mary, according to the 1870 U.S. census. After her death, he reportedly married Martha A. Baker in the late 1870s.

Bunn’s death date and place of interment are unknown. He is presumed to have died in Edgecombe County sometime before 1900.

* * * * * *

Hugh Cale (1838-1910) was born in Perquimans County, North Carolina, most likely in November 1838, believed to be the freeborn son of John Cail and his wife, Betsy. Little is known about Hugh Cale’s early life or when he moved to Elizabeth City, where he became a successful merchant.

Cale worked at Fort Hatteras and Roanoke Island for the Union army during the Civil War. After the War, he quickly became active in Elizabeth City’s political life, serving on the Pasquotank County Board of Commissioners for two years and as treasurer of Elizabeth City for four years, in addition to serving as a magistrate, poll inspector, and justice of the peace. His 1879 biographical sketch in the General Assembly sketchbook indicates he owned $12,000 worth of real estate that year.

In 1888, he served as a First Congressional District delegate to the G.O.P. national convention, and also as an alternate delegate from the First District to the conventions of 1884 and 1896. He became an A.M.E. Zion steward and a lifelong teetotaler after 1865.

Hugh Cale, member of General Assembly between 1877 and 1891. Photo courtesy Elizabeth City State University

Cale was elected as a Republican to four terms in the N.C. House of Representatives, in 1876, 1878, 1884, and 1890. During service in the 1877, 1879, 1885, and 1891 sessions of the General Assembly, his committee assignments included the following: (1879: Corporations, and Emigration; (1885) Corporations, Fishing Interests, Penitentiary, Insane Asylum, and Penal Institutions; and (1891) Fishing Interests. He was an unsuccessful candidate for reelection to the General Assembly in 1898.

Throughout his public career, Cale was dedicated to the cause of public education, serving on his county’s board of education during the 1880s and later as a trustee of two black colleges: Livingstone College and the North Carolina Agricultural and Mechanical College at Greensboro (1891-1899). During the 1891 General Assembly, he sponsored a successful bill to create a state normal school for blacks at Elizabeth City, the forerunner of present-day Elizabeth City State University.

In about 1900, Cale moved to Washington, D.C., where he worked for the U. S. government as a laborer. He had returned to Elizabeth City by April 1910, according to that year’s U.S. census.

He was married in June 1867 to his first wife, Mary Wilson, who died by 1895. In 1896, he married his second wife, Fanny Cale, who reportedly died in 1909. No children were recorded from either marriage.

Hugh Cale died on July 23, 1910, and is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in Elizabeth City.

* * * * * *

Wilson Carey (1831-1905) was born free in Amelia County, Virginia, on August 1, 1831. Carey [sometimes spelled Cary] attended school in Richmond before moving to North Carolina in 1855. As an adult, he was a farmer; after the War, he also became a merchant and schoolteacher, residing at Fitch’s Store, N.C.

Carey was a Caswell County delegate to the State Equal Rights League Convention of Freedmen in Raleigh in October 1866. In August 1869, Carey was appointed postmaster at Yanceyville, during the first term of President Ulysses S. Grant, but remained in office for just three months. He was briefly forced to leave the county in 1870-1871 by the Ku Klux Klan, according to some accounts.

He represented Caswell County at the 1868 and 1875 state constitutional conventions—the only African American delegate to both—and served as both a Caswell County commissioner (2 years, elected 1872) and magistrate (2 years).

Wilson Carey, member N.C. General Assembly between 1868 and 1889. Photo courtesy Caswell County Genealogy.org.

Carey was elected as a Republican to five terms in the N.C. House of Representatives, in 1868, 1874, 1876, 1878, and 1888, representing Caswell County in the 1868-1870, 1874, 1877, 1879, and 1889 sessions of the General Assembly. In 1870, he was also elected as a Republican to the N.C. Senate from the 24th District (Caswell County) but was not seated by the Senate. His committee assignments included the following: (1868) Corporations; (1874) Railroads, Postroads, and Turnpikes; and (1879) Education.

During the 1874 session, Carey joined eight other black legislators in protesting the enactment of the so-called “Amnesty Bill” passed by the House in November 1874. He was also one of 10 black legislators—joining two other white Republicans—to sign a formal protest against the earlier expulsion of newly-seated Republican House member J. Williams Thorne of Warren County, on grounds of allegedly not believing in God; earlier, he had been among 28 Republican legislators (11 of them black) to vote against expelling Thorne.

Carey was one of 14 signers of a public statement congratulating Ulysses S. Grant on his election to the U.S. presidency, published December 2, 1868, in the North Carolina Standard.

Carey married Francis (Fannie) Kimbrough of Caswell County in 1857. They had 15 children; eight were still living in 1879. After serving his last term in the House in 1889, Carey and his family moved to Washington, D.C., where Carey worked as a messenger for the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Carey died of natural causes in Washington, D.C., in 1905; his place of interment is unknown.

* * * * * *

John J. Newell (1836-1924), of Brown Marsh, Bladen County, was born in 1836 or 1839 in Wayne County, North Carolina, a son of Lydia and Charles Newell. According to biographical data he supplied to the North Carolina General Assembly Sketchbook, “(He) Never went to school a day in his life. What education he has attained was by applying himself during the spare moments from his work. Was bound out when only seven months old.” Despite limited formal education, he was able to read and write, according to the 1920 census.

Newell became active in Republican party politics after the Civil, serving as a Bladen County commissioner four years after 1872 and as a school commissioner for six years. Newell was subsequently elected as a Republican to four terms in the N.C. House of Representatives from Bladen County, in 1874, 1878, 1880, and 1882, and served in the 1875, 1879, 1881, and 1883 sessions of the General Assembly. His committee assignments included the following: (1874) Claims; (1879) Agriculture, Claims; (1881) Railroads, Post Roads and Turnpikes; Privileges and Elections; (1883) Committee on Emigration.

During the 1874 session, he joined eight other black legislators in protesting the enactment of the so-called “Amnesty Bill” passed by the House in November 1874. He was also one of 10 black legislators—joining two other white Republicans—to sign a formal protest against the earlier expulsion of newly-seated Republican House member J. Williams Thorne of Warren County, on grounds of allegedly not believing in God; earlier, he had been among 28 Republican legislators (11 of them black) to vote against expelling Thorne.

He was involved as the unwitting victim of a forgery scandal during the 1881 General Assembly, in which fellow member William W. Watson of Edgecombe County was alleged to have signed and cashed Newell’s per diem check without his knowledge. After a legislative trial, Watson was technically convicted of theft and forgery but narrowly escaped expulsion from the House, on a 44-25 vote, in which black legislators split their votes.

Newell married Mary Moriah Pittman on February 2, 1868; they reportedly had seven children. The 1880 census shows some of their names as Charles F., 12; John H., 6; daughter Savannah E., 10; Cora A., 2.

After the death of his wife, Newell died in Bladen County in 1924. Their exact burial location is not listed; their son, Johnie, who died in 1900, is buried in Clarkton Public African American Cemetery.

* * * * * *

James M. Watson (1842-1909) of Henderson was born on October 1, 1842, in Warren County. He moved to Henderson, then located in Granville County, in 1866, and attended Henderson’s high school. A carpenter and farmer, he became active in the Republican party after the Civil War ended, and served as a member of the new Vance County school committee in the 1880s.

Watson was elected as a Republican to four consecutive terms in the N.C. House of Representatives from Vance County, in 1886, 1888, 1890, and 1892. He served in the 1887, 1889, 1891, and 1893 sessions of the General Assembly. His committee assignments included the following: (1891) Counties, Cities, Towns and Townships; (1893) Deaf and Dumb Institutions.

He was married to Loucinda Bridgers in 1867; they had at least 10 children. Listed in the 1900 census were Mary N., James M., Lucy, Americus, Charles, Henry A., Pauline, John, Daniel, and Carolina Watson.

Watson died in Vance County in February 1909. His widow died there in 1939. They are presumed to be buried in Vance County.

* * * * * *

John Hendrick Williamson (1844-1911) was born a slave on October 3, 1844, in Covington, Georgia, the son of James Williamson and an unnamed mother, who were slaves of Gen. John N. Williamson. He moved with his widowed mistress to Louisburg, North Carolina, in 1858.

After the Civil War, Williamson was a Franklin County delegate to the State Equal Rights League Convention of Freedmen in October 1866. He soon became active in the Republican party, beginning with the 1868 state constitutional convention, to which he was a delegate. He later served as a vice president of the State Convention of African American Office Seekers in 1881, and in 1886, was a member of the State G.O.P. executive committee.

John H. Williamson, member of General Assembly between 1868 and 1887. Public domain engraving

He was elected as a Republican to five terms in the N.C. House of Representatives from Franklin County, in 1868, 1870, 1872, 1876, and 1886, and served in the 1868, 1870, 1872-1874, 1877, and 1887 sessions of the General Assembly. His committee assignments included the following: (1868-1869) Agriculture, Mechanics, and Mining; (1870-1872) Propositions and Grievances; (1887) Education, Agriculture, Deaf and Dumb and Blind Asylum, and Immigration.

Williamson was one of 14 black legislators who signed a public statement congratulating Ulysses S. Grant on his election to the presidency, printed December 2, 1868, in the North Carolina Standard. Williamson was also a delegate from the fourth Congressional District to the G.O.P. national nominating conventions in 1872, 1884, and 1888, and then served as an alternate delegate from the same district to the 1896 convention.

He helped found the Banner newspaper in 1881; it was merged with the Goldsboro Enterprise in 1883 (run by George A. Mebane and E. E. Smith). Williamson sold out his share, and started the North Carolina Gazette in Raleigh in 1884. He became a close friend of Josephus Daniels, influential Democrat and publisher of the Raleigh News and Observer, according to Daniels’s autobiography.

He was married to Clara A. Barnes on August 11, 1865. They had at least six children: daughters Ursula, Flora, Mamie, and Caroline, and sons James H. and John P. Williamson.

After a lengthy illness, Williamson died in a state hospital in Goldsboro in 1911. He is buried in the Louisburg City Cemetery.

Next time: Foreign Service Life in Jamaica, land of Red Stripe, reggae, and romance