More tales of North Carolina's 19th-century African American legislators

Part 1: The outliers, who went on to build lives elsewhere

I have previously introduced readers to a handful of African American legislators elected to the North Carolina General Assembly during the nineteenth century, among more than 125 black state legislators, all Republicans, who held office between 1868 and 1900.

This week, I continue my occasional series on North Carolina’s black public servants during the period, many of whom I have written about in previous articles for the North Carolina Historical Review. Today’s post explores the lives of a handful of legislators who left North Carolina to build productive lives in other states:

Thomas F. Benbury (1854-1943) was born in Parkville, North Carolina, a son of Esther White, enslaved in Perquimans County, and was possibly the son of his mother’s owner, also named Thomas Benbury. Trained as a carpenter, Benbury may have attended public schools after the Civil War. According to the 1870 census, he lived with his mother and two younger sisters in Perquimans County.

In the 1870s, Benbury moved to Edenton, in Chowan County, where he became active in Republican party politics. In 1880, he was elected to represent Chowan County in the 1881 General Assembly, one of 14 black members. He was well regarded enough assigned to three committees: Insurance; Salaries and Fees; and Agriculture, Mechanics and Mining. But he did not seek reelection in 1882.

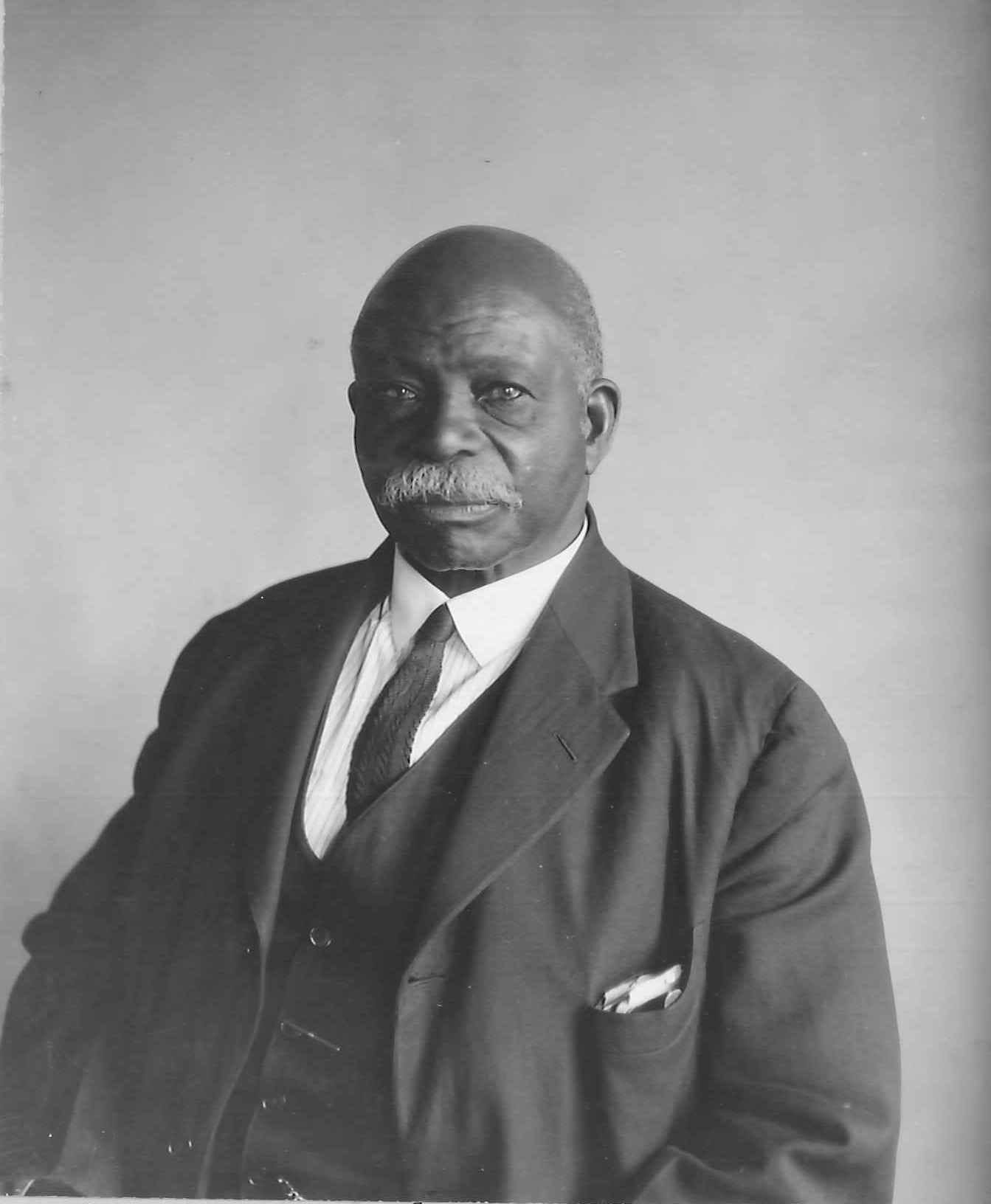

Thomas F. Benbury, member of the N.C. General Assembly from Chowan County in 1881. Photo courtesy Morgan Memorial Church, Boston.

That year, he married Dora Clifton Small, and the couple had at least two children by 1886, including son Clifton Benbury and daughter Ethel A. Benbury (Alford), both born in North Carolina. How much longer the Benbury family remained in Chowan County is not clear, but it appears likely that the family moved to Massachusetts around 1890. By 1900, the U.S. census records them as living in Suffolk County, Massachusetts, in the Boston area.

His occupation in 1900 was listed as church janitor. He eventually became evangelist and interim pastor of the church he had once served as a janitor—the Morgan Memorial Methodist Church of All Nations, which began its “colored congregation” about 1920.

Both Thomas and Dora were still living in Suffolk at the time of the 1930 and 1940 censuses; in the 1940 census, their ages were 84 and 77, respectively. In 1932, on the occasion of their 50th wedding anniversary, they received a “gold purse,” according to church records.

Thomas Benbury died in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on August 24, 1943; his widow Dora died there in 1945. Their burial place is unlisted, but is presumably in the Boston area.

* * * * * * *

William Patrick Mabson (1844-1916) was born about 1846 in Wilmington, the son of a wealthy white father and an enslaved mother named Eliza. His siblings included one sister, Bettie Ann Mabson; and three brothers, Whitfield S. Mabson, Bennie Mabson, and George L. Mabson, also a state legislator. Educated at Lincoln University (Pa.) just after the Civil War, he returned to North Carolina to work as a schoolteacher, settling in the Freedom Hill (Princeville) section of Edgecombe County, just outside Tarboro.

He soon became active in Republican party politics, and in 1872, was elected to the N. C. House of Representatives from Edgecombe County, but was expelled from the House on the grounds of technical ineligibility. Then, in 1874 and 1876, he was elected to the State Senate from the Fifth District (Edgecombe County), one of four members in 1875 and one of five member in the 1876-1877 session. Mabson was also chosen by county voters as a delegate to the state’s 1875 Constitutional Convention. In 1876, he served as a Second Congressional District delegate to the G.O.P. national nominating convention.

A school examiner for Edgecombe from 1873 to 1876, he was chosen as vice president of the Colored Educational Convention in Raleigh in 1877. He became principal of the county’s new school for black students at Princeville in 1883. Mabson unsuccessfully sought the G.O.P. congressional nomination for the “Black Second” District in 1878, losing that bid to James E. O’Hara. Under President Chester Arthur (1881-1885, he was appointed as a U.S. internal revenue “gauger.”

He and his wife, Louisa, had at least five children: sons William P. Jr., George W., and Benjamin, and daughters Louisa A. and Helen Mabson.

During unrest caused by a proposed strike by black farmworkers in 1889, Mabson was targeted by white landowners for his vocal support of the farmworkers; in 1890, he and more than 1,000 black county residents chose to emigrate to the West. Mabson moved his family to Texas, where they settled in Austin, the state capital. He became active as a businessman and journalist, publishing a weekly newspaper called the Searchlight. He was also described as a lawyer on his 1916 death certificate.

Mabson died in Travis County, Texas, on December 20, 1916, and is buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Austin. His lengthy obituary appeared in the Austin American-Statesman.

* * * * * * *

James W. Poe (1855-1921?) was born on February 18, 1855, in Ashe County, North Carolina. Educated at a parochial school, the Jefferson Academy, and the high school at Statesville, he became a schoolteacher in the 1870s and served in various schools, before moving to Ashland in Caswell County. In 1881, Poe served as master of ceremonies of the third annual exposition of the Industrial Association, held at Raleigh.

After serving as a delegate to the Republican party’s 1882 state convention in Raleigh, he was elected that year to represent Caswell County in the N.C. House of Representatives in the 1883 General Assembly, one of 16 black members. Five years later, he was also chosen as an alternate delegate from the state’s Fifth Congressional District to the 1888 GOP national convention, which nominated Benjamin Harrison for the presidency.

A longtime journalist, he was associate editor of the North Carolina Republican, published at Raleigh by James H. Harris, and later edited the Reidsville Piedmont Herald. Sometime after 1890, he moved to Washington, D.C., in part to attend Howard University, where he read the junior course of law and completed studies in 1894. During his residence, he worked as a claims agent and clerk for the U.S. Census Bureau, then as a clerk in the War Department’s office of records and pensions.

In 1905, Poe was licensed as an A.M.E. Zion minister, and became a Washington correspondent for the church organ, the Star of Zion, while also serving as editor of the Washington Axe and the National Leader. After 1910, he served as a correspondent for The Reformer, official organ of the Grand Fountain of the United Order of True Reformers, in Richmond, Virginia, and in January 1913, was named its editor, according to an account in the Washington Star.

In 1880, he married his wife, Sarah Emma Brown; they had at least 13 children, eight of whom were still living in 1910, according to that year’s census. They included sons James A., Virgil R., Edgar H., Elijah H., and Westley Poe; and one daughter, Julia Poe.

By 1920, Poe was listed as living alone in Richmond. His death date and place of interment are unknown, but he is presumed to have died in Richmond sometime after 1920.

* * * * * * *

Thomas A. Sykes (1835-1899?) was born in Pasquotank County, North Carolina, to an enslaved mother; his presumed father was her owner, a planter named Caleb Sykes. There is no record of any formal education for the young man, who moved to Elizabeth City after the Civil War, and quickly became active in the Republican party after serving as a delegate to the State Equal Rights League Convention of Freedmen in Raleigh in October 1866. In 1868, he was named to the party’s state executive committee and chosen as a magistrate in Elizabeth City.

That year, he was also elected to the first of two consecutive terms in the N.C. House of Representatives representing Pasquotank County, one of 17 black members. He was then named to the House committee on Privileges and Elections. Sykes was also one of 14 black legislators who signed a widely-publicized statement congratulating Ulysses S. Grant on his election to the presidency, printed December 2, 1868, in the North Carolina Standard newspaper.

Thomas A. Sykes, member of the N.C. General Assembly from Pasquotank County,1868-1872, and the Tennessee General Assembly, 1881-1893. Photo courtesy Tennessee House of Representatives, TSLA Collection.

Reelected to his seat in 1870, he was selected to serve on the House Committees on Public Buildings, Penal Institutions, and Enrolled Bills, as well as the joint House-Senate Committee on Per Diem. Following his legislative service in 1871, he was selected as a delegate from the First Congressional District to the 1872 G.O.P. national convention, which renominated Grant for the U.S. presidency.

Later in 1872, Sykes suddenly moved to Nashville, Tennessee, in part to accept a patronage appointment as a “gauger” for the Internal Revenue Service; the following year, he was promoted to I.R.S. assistant assessor, and later operated a house furnishing business. Selected as a Davidson County magistrate in 1876, he then returned to his gauger’s position from 1877 to 1881.

In 1880, he was elected to the Tennessee General Assembly, representing Davidson County as one of a handful of that body’s black Republican members. He introduced at least five important bills; one of them passed, admitting black students into state schools for the blind and deaf but housed in segregated facilities. But he declined to seek reelection, choosing to concentrate on his business interests. Still politically active, he became Tennessee’s leading black prohibitionist. In 1887, he became assistant superintendent of the new Tennessee Industrial School. In 1889, he was appointed janitor at the U.S. customs house in Nashville, where he remained until 1893, when he apparently left the city and disappeared from public records.

Sykes appears to have been married twice. His first wife, Martha Johnston Sykes, to whom he was married in Elizabeth City in 1866, had two daughters, but his family did not move to Nashville with him; she may have died in the 1870s or early 1880s. (He was listed as married, but living alone, in the 1880 census. ) Tennessee records indicates Sykes married again in the 1880s, this time to a schoolteacher named Viola Sykes. They were divorced in 1891, after an acrimonious trial that was well covered in local newspapers.

The date of his death and place of interment are unknown. He is presumed to have died in Tennessee sometime before 1900.

Next time: More tales of North Carolina’s 19th-century African American legislators