More tales of North Carolina's 19th-century African American legislators

Part 1: Pioneers elected to the 1868-1870 General Assembly

I have previously introduced readers to a handful of African American legislators elected to the North Carolina General Assembly during the nineteenth century, among more than 125 black state legislators, all Republicans, who held office between 1868 and 1900.

This week, I continue my occasional series on North Carolina’s black public servants during the period, many of whom I have written about in previous articles for the North Carolina Historical Review and in other publications. Today’s post explores the lives of some of the two dozen legislators who served in the first session of the General Assembly elected under provisions of the new 1868 state constitution:

Henry C. Cherry (1835/1836-1885), of Tarboro, served in the N.C. House from 1868 to 1870, representing Edgecombe County as a Republican. Born enslaved around 1836, either in nearby Beaufort County or Martin County, his father appears to have been named Joseph Blount Cherry, his mother an enslaved woman. Apparently emancipated before the Civil War, he moved to Tarboro, where he married Mary Ann Jones in March 1861. Together they had eight children, including two daughters, Louisa and Cora Lena, both schoolteachers, who married future Congressmen (Henry P. Cheatham and George H. White, respectively).

A carpenter by trade, he became a prosperous grocer and merchant after the War. He also became active in the new Republican Party, and was selected as a delegate from Edgecombe County to the state’s 1868 constitutional convention. Nominated by the Republicans to run for a seat in the N.C. House, Cherry was elected, and served in the N.C. General Assembly sessions of 1868 to 1870. He was appointed to the House Committee on Penal Institutions and the joint House-Senate Committee on Finance.

In addition to his legislative service, Cherry served as a Tarboro town commissioner for several terms, as well as a member of Edgecombe County’s board of commissioners and board of education. He was instrumental in the opening of a school for African American children at Freedom Hill (later known as Princeville), after writing a letter in 1868 to the American Missionary Association requesting assignment of an AMA teacher.

Cherry died of typhoid fever in July 1885; his burial site is unknown. He was survived by his wife, at least three daughters, and at least five sons, including Henry N. Cherry, who continued to operate his father’s business for a number of years.

* * * * * *

John S. W. Eagles (1843/1844-1901), of Wilmington, served one term in the N.C. House from 1869 to 1870, representing New Hanover County as a Republican. Probably born in northeastern North Carolina around 1843, Eagles moved to Wilmington after 1865. Little is known of his early life or education, except that he was literate, and was a trained carpenter.

During the Civil War, he served as a private/first sergeant in Company D, 37th U.S. Colored Infantry, organized in the Union-occupied northeastern sector of North Carolina, and was wounded by bayonet thrust at the Battle of the Crater, Petersburg.

In Wilmington, he became active in postwar Republican politics, and was elected in 1869 to replace member-elect L. G. Estes, who resigned before taking office. During the 1869-1870 session, Eagles served on the House Committee on Privileges and Elections. His 1870 reelection attempt was unsuccessful, as was a later attempt in 1876.

In addition to his legislative career, Eagles served as a Wilmington policeman, registrar, and election judge, and was also an active fireman. In 1870, he was listed in the U.S. census as owning $300 in real estate, and was an active member of St. Stephen’s A.M.E. Zion Church. Eagles was also active in the Grand Army of the Republic, and was reputedly the only African American commander of a GAR post.

During the Spanish-American War, Colonel Eagles was appointed in 1868 by Governor Daniel L. Russell to command the Fourth Volunteer Company for the U.S. Army.

Eagles married his wife, Maggie Loftin, on May 11, 1866. Their son John graduated from Shaw University’s pharmacy school, and became a prominent Charlotte druggist/physician.

Eagles died in Wilmington on July 17, 1901. He is buried in that city’s National Cemetery. His obituary was published in the Atlanta Constitution (July 21, 1901).

* * * * * * *

Richard Faulkner (1834/35-1896), of Warrenton, served in the N.C. House from 1868 to 1872, representing Warren County as a Republican. (His name is sometimes spelled Falkner.) Faulkner is believed to have been born in Warren County around 1835, possibly enslaved. He is also believed to have been a harness maker.

Faulkner was one of 17 black legislators to sign the “Address to the Colored People of North Carolina,” defending Gov. William Woods Holden against impeachment, dated December 19, 1870, and published in the Raleigh Sentinel on December 30, 1870.

Faulkner was also among the incorporators of the Warren County Co-operative Business Company authorized by the General Assembly in 1869. In 1870, he was listed by the U.S. census as owning $800 in real estate, $250 in property.

He may have been married to Cassie Falkner (as listed in the 1870 and 1880 censuses; as a widow in 1900). He was possibly an uncle of Henry Falkener, who also served in the N.C. General Assembly.

Faulkner died in Warren County in 1896. His place of interment is not known.

* * * * * * *

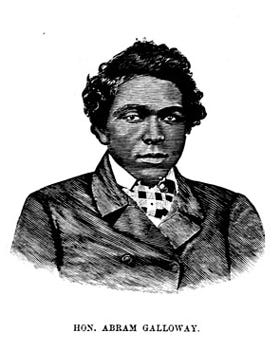

Abraham H. Galloway (1837-1870), of Wilmington, served in the N.C. Senate from 1868 to 1870, representing the 13th District as a Republican. Born enslaved in Georgia’s Brunswick County in 1837, he was the son of John Wesley Galloway, a planter and sea captain, and an enslaved mother. After escaping from slavery in 1857, he became an abolitionist, and returned to North Carolina as a spy for the Union Army in 1862.

According to his biographer, David Cecelski, Galloway “risked his life behind enemy lines, recruited black soldiers for the North, and … stood at the forefront of an African American political movement that flourished in the Union-occupied parts of North Carolina, even leading a historic delegation of black southerners to the White House to meet with President Lincoln and to demand the full rights of citizenship.”

Abraham H. Galloway of Wilmington served in the 1868-1869 N. C. General Assembly.

Engraving courtesy William Still's Underground Railroad (1872).

After the War, he moved to Wilmington, where he became active in the new Republican party, and was a New Hanover County delegate to the state’s 1868 Constitutional Convention. Chosen by the county’s Republicans as their nominee for the 13th District (New Hanover and Brunswick Counties), he was elected to that post in 1868, and served one term in the N.C. Senate in the 1868-1869 session of the General Assembly.

Galloway was subsequently reelected to the Senate in 1870, but died before taking office. His committee assignments included Propositions and Grievances, Military Affairs, State Prison and Penitentiary.

Galloway was one of 14 signers of a public statement congratulating Ulysses S. Grant on his election to the U.S. presidency, published December 2, 1868, by North Carolina Standard. He and his wife, Martha Ann Galloway, had two children.

Galloway reportedly survived an assassination attempt in 1870, but died of natural causes that same year on September 1, 1870; his funeral at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church was reportedly the largest held to date in the state (6,000 in attendance). He was reportedly buried in Wilmington’s Pine Forest Cemetery, although no gravestone remains.

David Cecelski’s 2012 biography is titled The Fire of Freedom: Abraham Galloway & The Slaves’ Civil War (UNC Press).

* * * * * * *

James Henry Harris (1835-1890), of Raleigh, served in the N.C. House of Representatives (1868-1870, 1883) and N. C. Senate (1872-1874), representing Wake County as a Republican. Harris was born in 1832 in North Carolina’s Granville County; his birth status is uncertain, but he was free by the time he moved to Raleigh in the early 1850s, where he became an upholsterer, teacher, and editor.

After the Civil War started, Harris apparently left for Ohio, and later claimed to have studied at Oberlin College, before traveling abroad to Canada, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. He helped raise troops for the 28th US Colored Troops, Indiana, in 1863.

After the War ended, Harris returned to North Carolina in 1865 as a schoolteacher, and attended that year’s state black convention. A Wake County delegate to the State Equal Rights League Convention of Freedmen in Raleigh in October 1866, he was elected president of the State Equal Rights League, and chaired the Colored Education Convention.

In 1867, he was a speaker for the Republican Congressional Committee. That same year, he reportedly turned down appointment by President Ulysses Grant as the new U.S. minister to Haiti. He served on the GOP State Executive Committee in 1886, according to the New York Times (September 23, 1886).

Harris served as a justice of the peace in Raleigh, and as a Wake County delegate to the 1868 constitutional convention. He was selected by Wake County Republicans as a nominee for a seat in the N.C. House of Representatives in 1868, and duly elected. During the 1868-1869 session of the General Assembly, he chaired the House Propositions and Grievances Committee, and served on both the House Judiciary Committee and the joint House-Senate Committee on Education.

He was subsequently elected to the N.C. Senate in 1872, representing the 18th District, and reelected to the N.C. House in 1882, serving his final term in the 1883 General Assembly. Active in statewide Republican politics, he was a delegate to six straight national GOP conventions (1868, 1872, 1876, 1880, 1884, and 1888). In other local offices, he was a Raleigh assessor and served four times on the board of aldermen (1868-1869, 1875-1876, 1877-1878, and 1887-1890).

In 1868, Harris declined the GOP nomination for Congress in the Fourth Congressional District, then ran as the nominee in 1870, but lost. In 1878, he ran unsuccessfully as an independent Republican in the Second District. He was also appointed as a U.S. deputy tax collector, and was appointed Superintendent of the N.C. Deaf and Dumb Asylum for Blacks.

In 1870, he owned $4,000 in real estate, $1,000 in property, according to the U.S. census. In the 1880s, he edited the N.C. Republican and the Raleigh Gazette.

He married his first wife, Isabella Hinton, about 1851. After her death, Harris married his second wife, Bettie Miller Harris, most likely in September 1885. He had at least two children, including a daughter, Florence, who died in 1889, and a son, David Henry Harris, who died in 1955.

By 1890, Harris had moved to Washington, D.C., where he died in May 1891. He is buried in Raleigh’s Mount Hope Cemetery. His front-page obituary was printed in the Raleigh News & Observer (June 2, 1891).

Next time: More tales of North Carolina’s 19th-century African American legislators