More tales of North Carolina’s 19th-century African American legislators

Part 1: Physicians, ministers ...

In a previous post, I introduced readers to a handful of African American lawyers who were elected to the North Carolina General Assembly during the nineteenth century, among more than 125 black state legislators, all Republicans, who held office between 1868 and 1900. Building on my decades of research into the life of George Henry White, who served in the 1881 and 1885 sessions, I continue my occasional series on obscure state legislators representing more than a dozen state counties during the period.

Most of the legislators were well educated, often attending or graduating from historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), including Shaw University, Lincoln University of Pennsylvania, and Howard University, and became physicians, schoolteachers, ministers, and journalists. A few were self-educated, but despite a lack of formal training, still managed to rise to positions of influence and respect in the African American community.

Following are brief biographies of four more of those legislators, some of whom I have written about at greater length in other venues, including in my 2001 biography, George Henry White: An Even Chance in the Race of Life (LSU Press), and in other books and published articles.

Physicians:

Eustace Edward Green (b. 1845; death date unknown), a native of Wilmington, was the son of an enslaved mother and an unnamed white father. Following the Civil War, he entered the local Presbyterian school for black students at age 20, and was quickly accepted at Lincoln University of Pennsylvania, where he completed bachelor’s and master’s degrees by 1875. After a brief career in South Carolina, he became principal of Wilington’s Williston graded school in 1878, and was tapped by Republicans as the party’s successful nominee for the State House of Representatives in 1882. He served with distinction on three committees in the N.C. House: Propositions and Grievances; Penal Institutions; and Education.

Soon after completing his single term in 1883, he decided to enter Howard University’s medical department, from which he graduated in 1886. In 1890, he moved his medical practice from Wilmington to Macon, Georgia, where he and his wife Georgianna—a daughter of former state legislator Henry C. Cherry of Tarboro—raised four children. In Georgia, he helped found the Central City Drug Store of Macon and served as president of the Georgia State Medical Association. Green’s brother-in-law was George Henry White, who served in Congress from North Carolina from 1897 to 1901.

A co-founder of the National Medical Association for black physicians, based in Atlanta, Dr. Green also served as its president. In the late 1920s, after his wife’s death, he moved to Detroit, Michigan, to live with their daughter, Mamie Green Alexander; he is presumed to have died there sometime after 1930, when the U.S. census last recorded his presence in her household.

Jacob H. Montgomery (1854-1911?) Born in Warrenton, North Carolina, in January 1854, Jacob Montgomery attended Raleigh’s Shaw University, after which he taught school in Warren County, and became active in Republican politics. He served as a vice president of the State Convention of African Office Seekers. Overwhelmingly elected as a Republican to the N.C. House of Representatives from Warren County in 1882, he served as one of 15 black House members in the 1883 General Assembly session, and was a member of the Committee on Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Institutions.

In 1884, he was chosen as a delegate from the Second Congressional District to the GOP National Convention, which nominated James G. Blaine for U.S. President. Later that year, he was nominated as a Republican and elected, again overwhelmingly, to the N. C. Senate from the 19th District (Warren County); one of three black state senators in the 1885 session of the General Assembly, he served on that body’s Education Committee.

In 1891, Montgomery entered Howard University’s Medical Department, from which he graduated in 1896. After completing medical training, he was employed by the U.S. War Department from 1896 until 1900, including the period of the brief Spanish-American War. Afterwards, he established a private practice in the DuPont Circle area of Washington, D.C. Never married, he was last recorded in the U.S. census as living in Washington, where he is presumed to have died sometime after 1910.

* * * * *

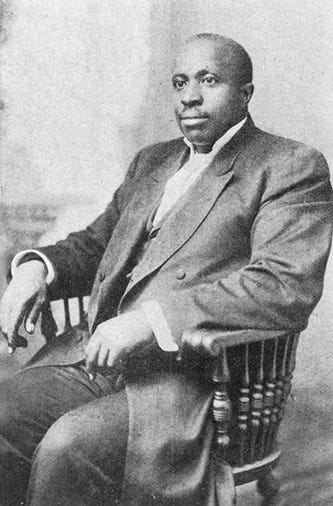

Rev. Thomas Oscar Fuller of Warrenton, who served in the

N.C. General Assembly, 1899-1900. Photo courtesy Schomburg Center

for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books

Division, The New York Public Library. The New York Public

Library Digital Collections. 1910.

Ministers:

Thomas Oscar Fuller (1867-1942) was born in Franklinton, North Carolina, and educated in the Franklinton Normal School. After graduating from Shaw University in 1890, Fuller became a Baptist minister and schoolteacher. While serving as a school principal in Warrenton, he was nominated by Republicans in 1898 to represent the 11th District (Warren and Vance Counties) in the N.C. Senate, and elected as that body’s only black member for the 1899-1900 session of the General Assembly, giving frequent speeches and successfully lobbying the Democratic majority not to reduce the number of state normal schools for training black schoolteachers, among other key issues. He unsuccessfully opposed the proposed constitutional amendment to impose a literacy test and restrict black suffrage, which was nonetheless passed by state voters in August 1900. Fuller was the Senate’s last black member until 1969.

After his legislative service ended, Reverend Fuller moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where he served as pastor of the First Baptist Church on Beale Street, and began a long association with the Howe Institute and the school into which it was merged, Rogers Williams College. He received a doctorate from the Agricultural and Normal School of Alabama in 1906, along with other advanced degrees from Shaw University. A prolific writer, he published at least six books, including Twenty Years in Public Life, 1890-1910, North Carolina-Tennessee. He is buried in New Park Cemetery in his adopted city, where he died in 1942. He was survived by wife and one son.

Prince Albert Hinton (1847-1922) was born to an enslaved mother near Newland in Pasquotank County, North Carolina. He taught himself to read and write before Emancipation. A gifted orator and preacher, he became active in the Roanoke Missionary Baptist Association after the Civil War. He also participated in Republican party politics, and was nominated by his party in 1886 to represent heavily-black Pasquotank County in the N.C. House of Representatives. Elected to that body in November of the same year, Hinton served one term in the 1887 General Assembly, among 15 black members in that year’s session.

After leaving the legislature, Reverend Hinton remained active in party politics, selected to serve on the county’s Republican executive committee in 1898, but held no other elected office. He took a strong interest in the establishment of a permanent normal school for training black schoolteachers. According to one biographical sketch, Hinton was among turn-of-the-century committee members who favored establishment of the “all-black state normal school that [later] became Elizabeth City State University.”

The committee wished to present the legislature with written proof of local support. But because his committee’s budget was so limited, Hinton “walked all the way there”—it took him a week to travel nearly 200 miles—while “carrying train fare for his return.” That bill, proposed by Hinton’s successor, Hugh Cale, was passed by the General Assembly on March 3, 1891.

In his later years, Hinton was hired as the keeper of the Episcopal cemetery in Elizabeth City. He was working at his post when fatally stricken by apoplexy in April 1922. He was 65 years old. Survivors included his widow, nine children, and 20 grandchildren.

Rev. Prince Albert Hinton of Pasquotank County, who served in the 1887 N.C.

General Assembly. Photo courtesy https://www.alberthinton.com/prince-albert.

* * * * * * *

Next time: Part 2: Schoolteachers, journalists …