More foreign affairs in a crazy, mixed-up world

Channeling Munich, 1938: Neville Chamberlain, Adolf Hitler, and "peace for our time"

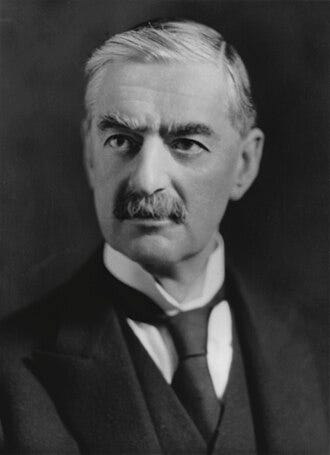

I grew up hearing, as a schoolboy, frequent reminders of the profound folly of Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister who declared “peace for our time” after handing Czechoslovakia over to Adolf Hitler in Munich in 1938—and a year later, found his country at war with Hitler.

But the so-called apostle of appeasement—who was forced to resign in May 1940, and sadly, died just six months later of cancer—was actually well respected personally in Great Britain, even by his far more illustrious successor, Winston Churchill. He has also undergone a kind of revisionist facelift in recent years by some historians, who believe he was “buying time” in a vain effort to help England prepare for inevitable war.

Neville Chamberlain, ill-fated British Prime Minister in 1938. Public domain photo

The story is actually far more complicated than the history books generally tend to show. Chamberlain’s noble aims were certainly popular in Britain in 1938—even supported by many in the United States at the time—although his reputation did not survive well for long outside Britain after 1940. But understanding his relationship to Winston Churchill is far more important.

The already-venerable Churchill—who later valued Chamberlain’s able political support after becoming prime minister himself in May 1940—had expressed his vocal doubts about the Munich pact early on, even before Munich, among the very few British politicians to question the wisdom of dealing with a dictator no one should ever have trusted.

In a damning speech delivered weeks later in Parliament on October 5, 1938, he condemned Munich as a “total and unmitigated defeat.”

“You were given the choice between war and dishonour. You chose dishonour and you will have war.

“And do not suppose that this is the end. This is only the beginning of the reckoning. This is only the first sip, the first foretaste of a bitter cup which will be proffered to us year by year unless by a supreme recovery of moral health and martial vigour, we arise again and take our stand for freedom as in the olden time.”

Winston Churchill, who somberly doubted the wisdom of the Munich Pact. Public domain photo

For his unwelcome candor, Churchill was roundly denounced and driven into the political wilderness by his Conservative party—until, of course, he was welcomed back as a compromise replacement for Chamberlain less than two years later. That he was proved right in such a short time did little to dispel the lingering sense of distrust many felt toward Churchill for having the temerity to speak out in 1938.

So it was with no small irony that I recently read recent news reports about a New Zealand diplomat who was disciplined—technically, fired from his post as “untenable”—for daring to raise the specter of Munich and Churchill’s warning at a think tank gathering of Europeans in London’s Chatham House.

Phil Goff, a former foreign minister and New Zealand’s current high commissioner to the United Kingdom, had the temerity to wonder aloud—in a pointed question—if the Finnish foreign minister, Elina Valtonen, thought U.S. President Donald Trump “really understands history.”

“I was re-reading Churchill’s speech to the House of Commons in 1938 after the Munich Agreement, and he turned to Chamberlain, he said, ‘You had the choice between war and dishonor. You chose dishonor, yet you will have war.’”

“President Trump has restored the bust of Churchill to the Oval Office,” added Goff. “But do you think he really understands history?”

According to CNN’s report, laughter prevailed in the audience, before Valtonen responded diplomatically and carefully: Churchill, she said, “made very timeless remarks.” That should have been the end of it. But not so fast …

Phil Goff, fired for voicing the question on everyone’s mind. Public domain photo

New Zealand’s controversial Foreign Minister, Winston Peters—a cranky, publicity-obsessed old man furious at being upstaged by a younger man he apparently dislikes—later fired Goff over his comments and “said he would have done the same if he had said something similar about other countries.

“If he (Goff) had made that comment about Germany, France, Tonga, or Samoa, I’d have been forced to act,” Peters told journalists. “It’s seriously regrettable and one of the most difficult things one has had to do in his whole career,” he added. “When you are in that position, you represent the government and the policies of the day; you’re not able to free think; you are the face of New Zealand.”

Peters’ reasoning was almost laughably inappropriate. An ironic, understated response— “inexperienced diplomats should think first”—would have served the same purpose, without backfiring on him. Did he bother to clear the decision with the Prime Minister, his boss? And Tonga? Who would be offended by questioning Tonga’s lack of leadership? And if he had asked the same question himself, would he have had to fire himself?

However, the sudden firing was not without its domestic critics, including former New Zealand Prime Minister (and former acting foreign minister) Helen Clark, who had once appointed Goff as Foreign Minister, one of his portfolios in her cabinet (1999-2008), before replacing him with Peters in 2005. She called it “a very thin excuse for sacking a highly respected former Foreign Minister from his post as High Commissioner to the UK,” in her posting on a widely-used social media platform, X.

Clark, among New Zealand’s longest-serving prime ministers, recently retired from her latest job at the UN, after leaving New Zealand’s quirky political scene. She is free to say whatever she pleases. She cannot be disciplined by Peters or anyone for voicing her opinion. But she notes, acidly, that many other other people have been raising the same question which got Goff fired.

“I have been at [the] Munich Security Conference recently where many drew parallels between Munich 1938 & US actions now.” New Zealand was represented at Munich in February by Defence Minister Judith Collins, who either didn’t get that memo—or didn’t report it to Peters. [See “New Zealand envoy to the UK fired,” March 6, https://www.cnn.com/2025/03/06/world/new-zealand-diplomat-goff-sacked-trump-scli-intl/index.html .]

A page back in time is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work,

consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

* * * * * *

I was a Foreign Service Officer for nearly 15 years at the U.S. Department of State. Among my favorite jobs was my third tour, working as a lowly press officer in the late 1980s for the Bureau of Public Affairs . There I helped the department’s spokesman, Charles Redman, prepare the “guidance book” for the daily press briefing. It was a complicated process—marshaling the resources of experienced officers in nearly every bureau on any given day to draft, clear, and compile guidance on a wide variety of issues likely to be raised by journalists when Chuck stood behind the podium in the press room.

I was a “runner,” tasked with helping send out requests for and retrieve cleared language to a handful of bureau contacts within a short period with a hard deadline. Generally, it worked like clockwork—not glamorous but absolutely integral to the appearance of diplomacy. The veteran newsmen and newswomen who gathered each day to quiz Chuck or his deputy, Phyllis Oakley, were adept at trying to pry any new morsel out of the sanitized diplo-speak, to get one of them to improvise and reveal something new and exciting.

Both were masters at the process—as longtime FSOs themselves, they knew better than to trip up. Both had Secretary George Shultz’s implicit trust, and an uncanny sense of just how far to push the canned guidance they were handed by the time our “vetting” process ended.

But occasionally, wittiness slipped in. Phyllis, married to a longtime ambassador, and a formidable presence on her own, was frustrated with one persistent needler at the briefing—who wasn’t satisfied with all he had heard on a nettlesome topic—and was tempted to snap a terse putdown. The answer she had given was all they could expect, she wanted to say, and if they couldn’t make a story out of that, tough bananas; to her—and everyone else—it was clear as mud. She was not going to be tricked.

So she turned to humor. “Look, if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, yes, I’d say it was a duck,” she said, in a friendly but firm tone, with a twinkle in her eye. Don’t mess with me, guys. It still made laughter and headlines, while winning Phyllis new admirers for grace under pressure.

Like Phyllis and Chuck, Phil Goff was a veteran—a former Foreign Minister himself—and knew every word he uttered as the Kiwis’ high commissioner in London was going to be reported, and widely, and in an uncertain world, perhaps not very favorably received in his own country—or by his famously-arch boss, suspicious of and impatient with the press under the best of circumstances—or in other countries trembling before the next shoe to fall from the erratic Trump administration.

This wasn’t Goff’s first rodeo. He belongs to his country’s Labour Party, Peters to the tiny New Zealand First party, which props up the current Labour-led coalition; both are accustomed to the risks of serving in coalition governments. And Goff is certainly no naive neophyte, like Marco Rubio, the timid new U.S. Secretary of State, who kept his mind and ears carefully closed in Munich—probably for fear he might be asked the burning question Helen Clark vividly recalls. He may not have expected to be fired for his question—but he certainly knew Peters was always out to steal the show, given his hair-trigger temper and Trump-like jealousy for the spotlight—and all-but- humorless attitude about being overshadowed.

Moreover, Goff raised a fair point—one Peters would never dare raising: Trump displays absolutely no discernible grasp of history, with all of its nuances, and only a marginal acquaintance with the legacy of far superior statesmen like Churchill, a brilliant historian whom he surely envies, probably, because he wrote thoughtful intelligent books, instead of signing his name to ghost-written guides to cheating in business. Or even like Chamberlain, for that matter, a thoughtful man who acted both nobly and foolishly, but seemingly fell into the cleverly-laid trap of believing Hitler’s fingers-crossed promises.

Goff, of course, was saying only what must keep so many sensible diplomats, like Valtonen—and not a few of the horrified world leaders they serve—up at night these days. He wasn’t speaking to journalists, per se, but lifting the curtain just a bit on what diplomats think privately—sharing a sort of private joke, if in front of journalists.

For unlike the childishly simplistic Donald Trump, European diplomats and leaders do understand history. They remember Hitler all too well, almost as it were yesterday. Munich was the world’s greatest diplomatic blunder, a resounding “don’t do this” to future generations. How could anyone have trusted a man who could barely read, blithered robotically through his interminable speeches without being able to pronounce half the words correctly, often didn’t know other leaders’ names, and simply would not listen to reason? Who threatened military action against his neighbors and “allies” because he coveted what they had?

Isn’t that, at its core, exactly what most people think happened at Munich? A deceitful promise signed with devastating results that Chamberlain simply could not fathom or even foresee? Chamberlain was an educated gentleman, and a consummate politician, if somewhat inexperienced as Britain’s prime minister. He had never flown before coming to Munich, and was tired and fretful. He was hoodwinked by the master deceiver, goes the conventional wisdom.

By contrast, Hitler was barely literate, a failed painter with no discernible talent for much else, until he found politics and became what passed for a spellbinding orator—and in a frighteningly sociopathic way, was disconnected from reality in his own world—but his genius, if you will, was that he was crazy like a fox. He knew how to charm gullible people like Chamberlain into giving him what he wanted—while preparing to stab them in the back, and make them thank him for it.

Hitler was supremely arrogant, and in fact, very good at lying to people—even those who suspected they were being lied to—and as the world would soon learn, even better at having them exterminated when it suited him.

Chamberlain was torn between wanting to be charmed by the murderous dictator’s snake-like words while personally disliking his ill manners. He privately confided to an advisor that Hitler was “without question the most detestable and bigoted man” with whom he had “to do business,” but still publicly praised him, for the sake of peace. Hitler was far less charitable, privately dismissing Chamberlain as an

“odd a—hole” who “haggled over every village.”

Adolf Hitler, still history’s most detestable man, in 1938. Photo courtesy German Federal Archive

* * * * * *

What does this mean for the rest of us, as we nervously watch what diplomatic blunder Trump pulls off next? That’s a question for the ages.

Yet I do not know that Trump can truly be likened to Hitler, as some claim. That misreads the historical situation. I am afraid, instead, that he is actually channeling, if in a rather skewed fashion, one side—but just one side—of the misguided and almost schizophrenic Neville Chamberlain.

For Trump, too, seems curiously naive and too certain of his own infallible judgment—if like an “angry little boy on a great white horse,” as David Brooks so aptly puts it. This two-dimensional caricature of a leader, easily susceptible to flattery and incapable of admitting a mistake, is desperate to believe that Vladimir Putin—another great man, like himself—can be trusted to keep his word, in spite of every horrid, brutal thing the murderous Putin has done since his days at the KGB. And once he has made his mind up, he will not tolerate even the slightest dissent.

If anyone is now channeling Hitler, I think it must be Vladimir Putin. And not without cause, worried observers now fear that a naive, shallow Trump, emulating the one thing he may recall about Chamberlain, will gladly sacrifice Ukraine—and perhaps next, the Baltics and Poland, all part of the new Soviet Union Putin is craftily reconstructing—if that will keep his fellow billionaire kleptocrat happy. He will gladly choose dishonor, even if he is not astute enough to perceive that what he does is in any way dishonorable.

What he cannot fathom, in his simplistic worldview, is that no deal will make Putin happy. Nothing will ever be enough. He is simply power-hungry. As with Hitler, there will always be something else he needs—and must have, or there will be hell to pay. For as with Hitler’s Mein Kampf, Putin has written it all down before, beginning with a ghost-written doctoral dissertation, then his “astonishingly frank” autobiography, First Person (published in 2000, just after he became Russia’s president); he fancies himself the reincarnation of Joseph Stalin, with all the forgettable royalty of a Russian Tsar. And a bewildered Trump is in awe of someone with even more arrogance, even bigger delusions than his.

I get eastern Ukraine, you get rare earth: Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump in 2017. Photo courtesy Evan Vucci/AP

However misguided or unlucky he was, Chamberlain was certainly not “dumb as a rock,” as Trump said about his first former Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson—a distinguished and very successful business leader who never went bankrupt—just after firing him. (Petty ravings, indeed. I wonder what he will have to say about Marco Rubio when he fires him for sheer obsequiousness. For some reason, the phrase “[expletive-deleted] moron” springs to mind, or on a less vulgar day, a dismissive “pipsqueak.”)

Perhaps Chamberlain, for all his faults, was at heart an idealist who thought he was saving England—and the world—from an unwanted war with a dangerous but politically expedient compromise. Except for Churchill, most British leaders, including later Nazi sympathizers, were certainly quick to praise him in 1938 for courage and moral leadership—at least for as long as they could do so, without enduring public ridicule, until the Nazi blitzkrieg began in 1940.

Unlike that other side of Chamberlain, however, Donald Trump does not often project either the sustained mental capacity or the serious thoughtfulness needed to be able to hold two contradictory views at once, weigh them, and choose one over the other. Too tiring for his 30-second attention span and stubborn childlike belief in his own omniscience. Easier to pick one, preferably one already vetted by Tucker Carlson or Fox News, and be done with it.

Tillerson himself had the last word on his former boss. “His understanding of global events, his understanding of global history, his understanding of U.S. history was really limited. It’s really hard to have a conversation with someone who doesn’t even understand the concept for why we’re talking about this,” he told a Foreign Policy interviewer about Trump in January 2021.

[See “Tillerson slams Trump,” January 15, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/01/15/politics/tillerson-foreign-policy-interview/index.html .]

* * * * * * *

At least for a while longer, global politics remains largely an old man’s world, led by increasingly crusty and bitter dinosaurs. All the major players are well into their 70s and beyond. Perhaps the 71-year-old Phil Goff, a former legislator and Auckland mayor who differs often with the soon 80-year-old Peters, was ready for retirement, and chose a very public way to show it. Or perhaps Goff was actually channeling a younger Rex Tillerson, now 72, who was fired at 65 by Trump for differing with him on one too many occasions (and showing one too many graphics at a briefing).

Perhaps Goff will even re-emerge in triumph one day, after Winston Peters—who is only a few months older than the U.S. leader he seems intent on defending—is himself fired, or finally retires. (Neither is likely.) I hope so—Goff is simply better at the craft than Peters, who distrusts the media—but I doubt New Zealand’s current leadership will be that brave or farsighted. Few politicians struggling to keep a coalition together ever are; just ask Germany’s Olaf Scholz about that, or France’s Emmanuel Macron, or Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu.

What strikes me as unseemly about the whole affair is not that Goff was fired for saying what he thought. No, not at all. What bothers me is that anyone, anywhere is expecting a different outcome in 2025 than in 1938, as the United States prepares to abandon Ukraine in an unsavory exchange for rights to its rare earth minerals, which no one may ever be able to extract from a heavily-mined landscape—and another improbable “peace for our time.” This time, it will be code for another war, another day, when president-for-life Putin is ready—one more reason why Trump envies him, no doubt.

We may be in for a long wait; at 72, Putin appears surprisingly vital, having apparently bathed in monkey glands, while the very weary-looking Trump, who turns 79 in June, suddenly seems so much older: a nearly-spent force off the stage, with a blotchy complexion after meditating too long in the tanning bed. He may be long gone when it happens. If so, we can only hope another leader with some brains, at least, and more day-to-day consistency has taken his place.

But to paraphrase Churchill’s words from 1938, after once choosing dishonor instead of war, we as a nation will still get war. Make no mistake about that.

Next time: More foreign affairs in a crazy, mixed-up world.

Now there's a frightening video! Thanks for sharing--Ben

Thank you for this piece . . .