More foreign affairs in a crazy, mixed-up world

Part Two: Making a flimsy case even worse, by punishing the innocent recipients of high-quality medical care by Cuban providers

This is a continuation of my recent entry dealing with the results of the Trump administration’s so-called “extortion diplomacy,” as practiced against—but not restricted to—the smaller governments of the Caribbean in recent months.

Miniscule Marco Rubio is convinced he has found a platform that will make him famous: depriving needy recipients of high-quality medical care in as many countries as he can find—and giving the finger to anyone who disagrees with him. But that platform will give the United States a permanent black eye diplomatically, while depriving hundreds of thousands of innocent foreign citizens of even the most basic health care.

The U.S. Secretary of State last week entered a new phase of his long and unprincipled anti-Cuban campaign by revoking U.S. visas granted to certain leaders in Grenada, Brazil, and an unspecified number of African nations—a clear indication that to Miniscule Marco, at least, diplomatic niceties are expendable in countries that piss him off by arguing—for “complicity in the Cuban regime’s medical mission scheme.”

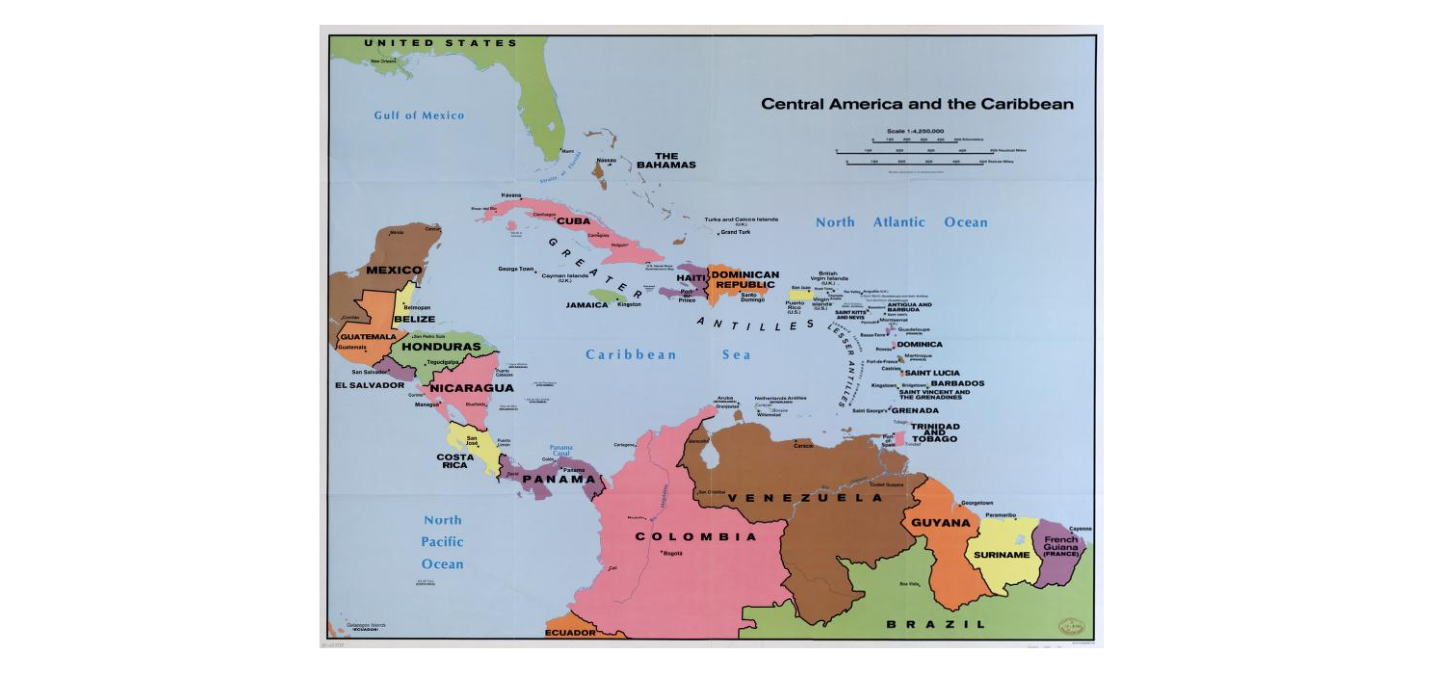

Map of the Caribbean Sea and surrounding areas. Courtesy Library of Congress

It is a mind-blowing precedent, with dangerous implications. The latest revocations are only the first in a long series of questionable actions likely to be taken on personal whim by the Trump administration, and may not be limited to anyone with a Cuban-trained doctor or nurse on duty. Next, presumably, will be any nation who dares to recognize Palestine—as Canada and the United Kingdom have threatened to do soon, and even some Caribbean nations have discussed doing, over the continuing Israeli war against Gaza—or who stubbornly refuses to accept third-country deportees.

How long before any country who refuses to end its lucrative “golden passport” program—Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, St. Kitts, and St. Lucia—ends up in the same predicament? And will it eventually include the prime ministers or presidents of offending states—a daring and counterproductive strategy at the very least, but certainly not out of the question—and perhaps provoking unprecedented diplomatic consequences?

Russia and Israel, of course, remain technically off limits to high-level visa revocations in Trump 2.0. Despite the war crimes for which Vladimir Putin and Binyamin Netanyahu could legally be arrested almost anywhere else in the world, they can still travel with almost criminal ease into the United States to be feted by our own Dear Leader, with Miniscule Marco’s vapid assistance.

But the far-reaching tentacles of the new “extortion diplomacy” practiced by the Trump administration—reminiscent of the unethical and evil strategies once routinely practiced by the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany—appear to reach almost everywhere else in the world

A page back in time ... is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work,

please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

* * * * * * * * * *

As a “reformed” Foreign Service Officer—I walked away from the U.S. State Department in 1997—I keep my eyes out for unusual and outrageous events occurring in countries of interest to the United States, particularly those I have served in or visited. This often includes analyses of U.S. actions affecting those countries, whether wise or effective—or neither, as here—and in many recent cases, more puzzling than practical.

I have never visited or served in Grenada, although I am familiar with many of its Caribbean neighbors. As a fledgling consular officer in 1983, I did serve in Jamaica when that country’s government—headed by former Prime Minister Edward Seaga—joined Reagan in supporting the Grenada incursion, as part of his anti-Communist strategy against Cuba, which had strongly supported the late Maurice Bishop’s Socialist government.

Anti-Cuban rhetoric, including the transparently silly “human trafficking” charges now being leveled, have prevailed under Republican administrations in recent decades. As a Florida politician, Rubio has campaigned relentlessly for years against the malevolence of Cuba, the island where his parents were born, with an almost religious zealotry, particularly after he lost the Republican presidential nomination to Trump in 2016.

Rubio began his latest tirade against Cuba shortly after being sworn in as the nation’s top diplomat in January. In an official announcement issued in late February, he announced plans to expand an existing policy, one rarely enforced—targeting Cuban leaders and others, at first, Venezuelans—for supporting “forced labor linked to the Cuban labor export program.”

This expanded policy applies to current or former Cuban government officials, and other individuals, including foreign government officials, who are believed to be responsible for, or involved in, the Cuban labor export program, particularly Cuba’s overseas medical missions. This policy also applies to the immediate family of such persons. …

Cuba continues to profit from the forced labor of its workers and the regime’s abusive and coercive labor practices are well documented. Cuba’s labor export programs, which include the medical missions, enrich the Cuban regime, and in the case of Cuba’s overseas medical missions, deprive ordinary Cubans of the medical care they desperately need in their home country. The United States is committed to countering forced labor practices around the globe. To do so, we must promote accountability not just for Cuban officials responsible for these policies, but also those complicit in the exploitation and forced labor of Cuban workers. [Italics above for emphasis are the author’s.]

This visa restriction policy is taken pursuant to Section 212(a)(3)(C) of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

Grenada, that gorgeous island in the Eastern Caribbean once “rescued” from Socialist ruin by President Ronald Reagan in 1983, is one of the Caribbean Community (Caricom) countries who have entered into contracts with the Cuban government for utilization of its doctors, nurses, and other medical support personnel. The small island (population 117,000) has only a bare-bones health care structure, with only one very expensive, for-profit medical school (St. George’s University, founded 1976) which caters largely to U.S. students seeking a “second chance,” and who do not stay behind after graduating, according to the New York Times [see “Second-Chance Med School,” July 31, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/03/education/edlife/second-chance-med-school.html .].

Like many small countries, Grenada must therefore depend on foreign medical schools to train a significant portion of its health care providers. Cuba has stepped in to fill that vacuum, training more than 400 of Grenada’s medical practitioners for free since Grenada reinstated its diplomatic relations with Cuba in 1994—and providing a large number of Cuban-trained personnel to practice in Grenada alongside them, an “indispensable” number without whom the island’s medical care system would “collapse,” according to its foreign minister.

St. George’s, the picturesque capital of beleagured Grenada. Courtesy Encyclopedia Britannica

Grenada’s leaders are understandably proud of that win-win relationship. Foreign Minister Joseph Andall—himself a graduate of a Cuban university—told the Miami Herald that “Regarding the charges of so-called forced labor and human trafficking, we will never be party to anything of that nature … Grenada respects all international conventions and protocols regarding the protection of human dignity, and we are quite satisfied that the Cuban medical program with us is totally above board and in compliance with our international labor and human rights standards. So we have no qualms about being able to defend them.”

Grenada’s health care system would “collapse” without its “indispensable” Cuban medical contract personnel, Andall insisted. He provided no hard numbers, but has previously said it includes specialists such as psychiatrists and radiologists. [See Jacqueline Charles, “Grenada Foreign Minister rejects U.S. claims,” August 15, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/cuba/article311716616.html .]

Rubio’s wooden-headed plan ignores the many advantages offered Grenada by the Cuban medical brigade. He is relentlessly determined, instead, to punish Grenada for having anything to do with Cuba—and to warn anyone else in the Caribbean, especially, about the consequences of acting against U.S. wishes, however irrational they may be.

* * * * * * * *

Grenada is still awaiting specific details on who among its leadership might be forced to relinquish their U.S. visas—both Andall and Finance Minister Dennis Cornwall are believed to be prime candidates—but the far larger nation of Brazil is reportedly furious over Rubio’s decision, apparently falsely targeting its Health Ministry official Mozart Julio Tabosa Sales, according to a separate Reuters report, for allegedly helping circumvent the Brazilian constitution.

Brazilian Health Minister Alexandre Padilha said his government will not bow to what he called "unreasonable attacks" on Brazil's Mais Medicos, or "More Doctors," program mentioned by Rubio. The program was created in 2013. Cuba's contract in it was terminated in 2018.

In addition, former Ministry of Health official Alberto Kleiman, later with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), was singled out for visa revocation. He and Tabosa Sales reportedly worked closely with PAHO to administer the Mais Medicos program between 2013 and 2018. [PAHO is the regional affiliate of the World Health Organization (WHO), the UN organization from which the Trump administration has recently withdrawn; both WHO and PAHO are now widely condemned within Trump circles.]

That the revocations stem from long-ago actions that were apparently perfectly legal at the time—if loudly objected to by Trump officials and Bolsonaro, after the fact—seems a rational fact completely lost on Miniscule Marco. The visa revocations announced by Rubio clearly seem focused on the past, reinforcing a wave of vindictive retribution against the Lula administration for its continuing prosecution of Bolsonaro—Trump’s closest Western Hemisphere ally during his own first administration—for attempting to steal the 2022 election, in which he was defeated.

Dear Leader has made no secret of that as the reason for his 50 percent tariff—highest in the world—he ordered imposed on Brazil earlier this month. Or less openly, for the U.S. sanctions he authorized against the Brazilian judge involved in the case.

[See “US to impose visa restrictions on officials,” August 14, https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/us-impose-visa-restrictions-officials-alleging-ties-cuban-labor-program-2025-08-13/ .]

A Mais Medicos presentation in Brasilia, 2023. Public domain photo

The original Mais Medicos program of 2013, created by former President Dilma Rousseff to bolster the poor quality of Brazil’s rural medical programs, cost more than US$1 billion and brought thousands of Cuban medical personnel to a rural swath of Brazil; it was ended in 2018 by former President Jair Bolsonaro, when all Cuban personnel were withdrawn. The reinstated version of Mais Medicos—created by President Lula in 2023—has yet to approach previous levels, with some 5,000 vacancies remaining; preference is now given to Brazilian-trained doctors. [See “Brazil announces its new Mais Medicos,” March 20, 2023, https://www.gov.br/planalto/en/latest-news/2023/03/brazil-announces-its-new-mais-medicos-para-o-brazil-program .]

Miniscule Marco gives visa-holders, including those in Brazil, a warning finger. Courtesy New York Times

Two statements on revocations were issued by Rubio on August 13, the first aimed at Brazil. [See “Visa Revocations and Restrictions on Brazilian Government,” August 13, https://www.state.gov/releases/office-of-the-spokesperson/2025/08/visa-revocations-and-restrictions-on-brazilian-government-officials-and-former-paho-officials-involved-in-the-cuban-regimes- .]

The second was aimed at “African, Cuban, and Grenadian government officials, and their family members.”

Today, the Department of State took steps to impose visa restrictions on African, Cuban, and Grenadian government officials, and their family members, for their complicity in the Cuban regime’s medical mission scheme in which medical professionals are ‘rented’ by other countries at high prices and most of the revenue is kept by the Cuban authorities. This scheme enriches the corrupt Cuban regime while depriving the Cuban people of essential medical care.

The United States continues to engage governments, and will take action as needed, to bring an end to such forced labor. We urge governments to pay the doctors directly for their services, not the regime slave masters.

The United States aims to support the Cuban people in their pursuit of freedom and dignity and promote accountability for those who perpetuate their exploitation. We call on all nations that support democracy and human rights to join us in this effort to confront the Cuban regime’s abuses and stand with the Cuban people. [Italics for emphasis are the author’s.]

[See https://www.state.gov/releases/office-of-the-spokesperson/2025/08/visa-restrictions-on-african-cuban-and-grenadian-government-officials-involved-in-the-cuban-regimes-coercive-forced-labor-export-scheme#:~:text=Today%2C%20the%20Department%20of%20State,and%20most%20of%20the%20revenue .]

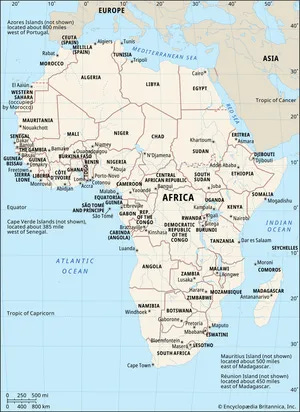

Neither of the official State Department statements listed any of the African nations being targeted by the visa revocations, but South Africa—with several hundred Cuban doctors reportedly serving in a longstanding arrangement—is presumably high on the list of “possibles,” based on the strained state of its diplomatic relationship with the United States in 2025. Among early actions taken by Rubio on behalf of Trump was the immediate expulsion of the new South African ambassador to the United States. alleging he had publicly maligned the Dear Leader.

The continent of Africa. Map courtesy Encyclopedia Britannica

The number of African nations currently participating—some for free, others paying reduced rates—in the Cuban medical brigade program is not clear: perhaps 20, according to the Cuban government. Those listed in a comprehensive 2025 report by Wellcome Open Research include South Africa, Kenya, Gambia, Cape Verde, Angola, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Nigeria, Ghana, DRC [Democratic Republic of Congo], and Liberia. [See “Experiences with the Implementation of Cuban Health Cooperation Programs,” https://wellcomeopenresearch.org/articles/10-167 .]

In addition to the Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM), the world’s largest medical school, where 29,000 students from 105 countries have graduated since 1999, Cuba also operates a dozen medical schools abroad, including African schools in Ethiopia, Guinea Bissau, Uganda, Ghana, Gambia, and Equatorial Guinea. (Question for Miniscule Marco: How many free medical schools does the United States operate?)

Cuba has clearly been using its medical brigade as an effective diplomatic tool over recent decades, and it has generally been lucrative in terms of much-needed foreign currency—if declining somewhat recently since Brazil ended its contract in 2018. It has served missions in more than 150 countries since its creation in the early 1960s, with a generally positive response from most recipients.

Not surprisingly, its government rejected the Trump administration’s recent moves as “a smear campaign” against its doctors and the medical assistance program. [See “U.S. revokes visas,” August 15, https://oncubanews.com/en/cuba-usa/u-s-revokes-visas-for-african-brazilian-and-paho-officials-for-hiring-cuban-medical-missions/ .] According to Reuters, “Cuba's medical cooperation will continue,” Johana Tablada, Cuba's deputy director of U.S. affairs, said demurely on X. “His (Rubio’s) priorities speak volumes: financing Israel genocide on Palestine, torturing Cuba, going after health care services for those who need them most.”

I do not claim to be an expert on the pros and cons of the Cuban medical brigade, or the tactics of its operations around the world. I have no love for the Cuban government or its dreadful handling of its own economy or its political prisons. But to me, the whole Trump administration vendetta against Cuba now smacks of an almost Shakespearean obsession with protesting too much—although that would suggest that anyone in Trump’s world has ever read Shakespeare, or anything to the left of ONAN or Fox News reports.

Is the Cuban medical brigade a perfect solution to the health needs of the developing world? Probably not, though in my mind, it is certainly far better than nothing—which is what Rubio suggests substituting. And yes, the Cuban government may well be exploiting the talents of those it sends abroad by keeping most of the salaries they receive. Yet it is worth noting that these doctors and nurses were trained—and quite well—for free, and some no doubt may consider it their patriotic duty to repay the government by serving abroad, as do U.S. military doctors whose medical school tuition is funded by the U.S. government in exchange for years of service afterward.

Few of the Cubans living abroad are willing to speak publicly about the system—understandably leery of calling attention to themselves or alienating their famously-secretive and punitive Communist government. And while some of those Cubans living abroad have indeed grumbled privately about their treatment, it is still a far cry from slavery or human trafficking—and most do still fare far better in more congenial foreign settings than they would at home.

The essential truth appears to be that the Cuban medical brigade, flawed as it is, fills a genuine need through the world, especially in poorer countries whose medical systems are less well developed. Millions of foreign citizens who would have received little or no medical care at all are alive today only because of the Cuban program.

What Miniscule Marco does not seem to be able to grasp is just how much the program is valued throughout the world—which he relegates simple-mindedly to an “abuse” of human rights not worth continuing. Nor can he comprehend how hypocritical it must seem to nations who have watched U.S. foreign aid, including our far more limited medical cooperation, collapse overnight—with no alternative in most cases to Cuba’s extended hand.

Miniscule Marco is simply blind to any facts that might cloud his zealous overreach. Once vaunted as a prudent and well-prepared expert on foreign relations in the U.S. Senate, he has melted down since assuming office into an ignorant MAGA parrot, a puppet of the Dear Leader who jerks convulsively whenever his strings are pulled.

His performance thus far does not augur well for the future of this country’s once-proud role as a world power—nor for the future of diplomacy in general.

Wherever this all-out U.S. war on diplomacy is leading, it is not going to end well for Miniscule Marco—or pleasantly for anyone involved abroad. Stay tuned for further developments.

Next week: More foreign affairs in a crazy, mixed-up world