More foreign affairs in a crazy, mixed-up world

A fool's game: Ignoring the experts and trusting the Russians

Almost every U.S. president since George Washington has called upon private citizens to serve as special envoys to adversary countries—those with whom our relations are especially delicate, tricky, or unpredictable. In some cases, the president simply wants someone he knows well and trusts—perhaps even a personal friend, as Trump with Steven Witkoff—to act on his behalf, often reporting confidentially to the Secretary of State or White House outside the normal diplomatic channels.

But few in our history have been given multiple unrelated tasks at once—or like Steven Witkoff, have succeeded at one while failing miserably at another.

Most succeed in their assigned missions, some admirably, because they come prepared, with a clear-eyed goal and knowledge of previous encounters. The key to their success is almost always their ability to marshal all available resources, and to know where to find it quickly and effectively. Not all may speak a particular foreign language, but wisely amplify their negotiating skills with assistance from experienced U.S. Embassy officials in their region, are trained in that language, as translators, and who can provide critical context during oft-demanding negotiations.

Few fail miserably—because even when they are less than completely prepared, they have dependable teams of assistants and translators, if needed, to keep them afloat. That brings us to the sad case of Witkoff, who has violated almost every protocol in the history of negotiations, and so far, come up empty-handed so far in his Russian adventure, at least. He is failing, and miserably so, because he is wearing blinders—and, apparently, earplugs as well—while Trump smiles malevolently from the sidelines.

In fairness to him, of course, he was hired as a special envoy for the Middle East—where he at least stood a chance of looking as if he might succeed. At least Israelis and most Middle Eastern leaders are willing to negotiate in English—and Witkoff, who is Jewish, if not always an observant one, has at least some limited grasp of the complex cultural situation. “Many regional officials see Witkoff ‘as a more even-handed negotiator and interlocutor’ than past American counterparts,” writes the Huffington Post, for instance.

Yet Witkoff’s willingness to ignore normal protocols—as well as his shameless flaunting of his thirty-something girlfriend on these trips—trouble other observers:

He has [already] become known for little coordination with other American officials, traversing regional capitals on his private jet with a handful of close aides, many of them young and without national security experience, as well as private business contacts interested in real estate opportunities in the Middle East, the former U.S. official said.

Witkoff insisted that Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu interrupt his Sabbath observance to meet Witkoff with almost no warning; Netanyahu grumbled, but acquiesced. [See “A moment of truth in the Middle East,” May 12, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/trump-middle-east-steve-witkoff_n_68223a9ae4b04d30c1c9bf96 .]

By contrast, that is one reason why Steven Witkoff’s one-on-one “negotiations” with Vladimir Putin are almost laughably unproductive. He may actually think of himself be a tenacious negotiator in real estate matters, with some justification, or in a U.S. courtroom—but he has absolutely no idea who he is up against in Moscow: a master manipulator and liar, a murderous tyrant who began his career as a KGB spy, and shows no signs of mellowing at the end of his life.

So far, Witkoff has only commented favorably on Putin’s willingness to cooperate—with no verifiable evidence of that at all—and tended to agree readily with scenarios advanced by Russia, and slavishly parroted by Trump: that Ukraine is somehow responsible for the war in the first place, and unwilling to “compromise,” particularly over the status of Ukrainian territory illegally occupied by Russia. Each time Ukraine voices an objection, a glib Russo-favorable answer overrides all.

Small wonder why. He is operating without most of the facts. According to one NBC News report in May, Witkoff

… broke with long-standing protocol by not employing his own interpreter during three high-level meetings with Russia’s Vladimir Putin, opting instead to rely on translators from the Kremlin, a U.S. official and two Western officials with knowledge of the talks told NBC News. Steve Witkoff, who has been tasked with negotiating an end to the war in Ukraine, met with Putin in Moscow for several hours on Feb. 11, on March 13, and in St. Petersburg on April 11, and “used their translators,” one of the Western officials said.

[See “Trump envoy relied on Kremlin interpreter,” May 10, https://www.nbcnews.com/world/russia/russia-ukraine-war-trump-envoy-witkoff-interpreter-kremlin-rcna205878 .]

At best, Witkoff is an under-equipped amateur, a stand-in for Trump. At worst, he is a poorly-informed novice who has little to offer in these life-or-death peace negotiations, and is in way over his head. He may have Trump’s trust, but that and 500 rubles will get him a cup of sour chai on any Moscow street, and nothing else.

Witkoff (left) meets chief Russian propagandist Sergey Lavrov (right) in Riyadh. Public domain photo

A page back in time ... is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work,

consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

* * * * * * *

The least effective presidential special envoys are often those who have vaguely-defined missions, and must therefore rely on their instincts. Businessmen or lawyers with no real “feel” for sensitive negotiations must “wing it,” and those who refuse to use advisors familiar with the local culture—in favor of mostly wet-behind-the-ears sycophants, like Witkoff—have even smaller chances of success. In the worst possible cases, like Witkoff’s, they stubbornly refuse to employ impartial translators of a foreign language they do not speak—and depend instead on translators provided by the government or leader with whom they are dealing.

This is, of course, a counterproductive technique Witkoff has learned by osmosis: watching the man who employs him—the Orange Emperor himself, who has always refused to allow notes to be kept of his private meetings with Putin, apparently because he does not trust anyone who is even vaguely impartial, and wants no record of the details to interfere with his pre-ordained public announcements afterward.

The Russians are doubtless rubbing their hands with glee every time Witkoff steps off a plane. In the common parlance, he is a useful idiot—like Trump, an arrogant one, perhaps, with a very high opinion of himself, but totally unaware he is being played for a fool.

According to nonprofit Ballotpedia.org, special envoys are “agents appointed as the personal representative of the president or the secretary of state. They are often appointed in response to congressional or public attention to a particular region or issue.

Special envoys can operate outside of the typical reach of a single-country ambassador to address complex, multilateral issues. Since they are responsive to the needs of each administration, there is no set number of special envoys. President George Washington made the first such temporary diplomatic appointment in 1789, naming a private agent focused on normalizing diplomatic relations with Britain.

President Joe Biden appointed 46 special envoys between 2021 and 2025, many chosen to pursue thematic goals—international religious freedom, or monitoring human trafficking—but others assigned to specific countries (Yemen, North Korea) or situations. About a dozen of those envoys were active or former Foreign Service Officers. [See https://ballotpedia.org/Special_envoys_by_administration .]

While most envoys are not diplomats by training—many are instead former politicians, or successful businessmen with strong public reputations—some special envoys have performed extraordinarily well in extremely difficult diplomatic situations. Take former Senator George Mitchell, who performed admirably in a long public stint in Northern Ireland for President Clinton (1995-2001), helping construct the Good Friday Accords, and later worked for President Obama in the Middle East (2009-2011).

Such was the case in early 1993, when newly-inaugurated President Bill Clinton drew upon his lifelong friendship with a gifted journalist and fellow Rhodes Scholar, Strobe Talbott, to become Ambassador-at-Large and Special Adviser to the Secretary of State on the New Independent States (NIS). This was after the collapse of the former Soviet Union and the formation of more than a dozen new countries across Eastern Europe, Asia, and the South Caucasus.

In that instance, Talbott was a perfect choice. As a fluent Russian speaker, he was able to converse with leaders in both the new Russian Federation—successor to the bulk of the old USSR—and with many of the leaders of the new independent nations, who had been educated in Russian schools and who spoke both their native languages and Russian. In 1994, he was appointed as Deputy Secretary of State, a position he held until 2001.

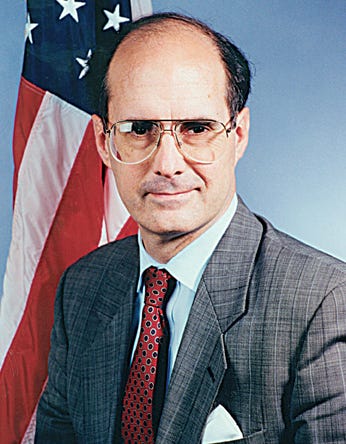

Others perform their tasks just as well but far more quietly, negotiating largely outside the public limelight to achieve a specific task—like veteran U.S. diplomat Robert Frasure, U.S. envoy to the Contact Group [the United States and four other nations] during the Balkan Wars, who helped negotiate a workable peace plan with Serbian leaders before his tragic death in a vehicle accident near Sarajevo in 1995. [See “Robert C. Frasure, 53, envoy on Bosnia mission, is killed,” August 20, 1995, https://www.nytimes.com/1995/08/20/obituaries/robert-c-frasure-53-envoy-on-bosnia-mission-is-killed.html .]

* * * * * * *

As a “reformed” Foreign Service Officer—I walked away from the U.S. State Department in 1997, after serving roughly 15 years—I keep my eyes out for unusual and outrageous events occurring in countries of interest to the United States, particularly those I have served in or visited. This often includes analyses of U.S. actions affecting those countries, whether wise or effective—or puzzling, as here—and in some cases, simply mind-boggling.

I knew Bob Frasure when he was U.S. ambassador to Estonia, next door to Latvia, where I was assigned as administrative officer in Riga in 1992. I spent much time in Tallinn on frequent trips to Helsinki, and quickly came to know Bob well. I don’t think I ever met a finer Foreign Service Officer—funny, quick-witted, humble, a gifted writer, exceptionally hard-working, a fellow who easily inspired his employees and got much more out of them as a result, despite his Ph.D. from Duke (an inside joke—I was a Carolina graduate!)—and no trace of the cynical, brusque egotism displayed by most career ambassadors.

When I attended his funeral in Arlington in 1995, I was working as a Russian disarmament watch officer. Like almost everyone else there, I mourned his early death, which left a distinct void in the often-moribund and gloomy Department of State.

Ambassador Bob Frasure, taken from us far too soon. Public domain photo

I also knew Strobe Talbott, whose intellect I greatly admired, but he was a far different kind of leader: an intimidating one, frankly, almost frightening. Even veteran Russian-speaking officers in the Nuclear Risk Reduction Center, where I worked, dreaded running into him on the Seventh Floor—because the former Time Magazine writer would immediately strike up a conversation in perfect Russian, like a native. He expected you to answer back in equally flawless Russian—and worse, to be as well informed as he was.

Few of us had the capacity to do that—and suffered a professorial critique when we failed: the worst possible nightmare of graduate school, an oral exam on the job. Yet as a negotiator and envoy, he was a man of near-matchless ability—fearless, effective, yet comfortable in his own skin.

Strobe Talbott, author and diplomat. Courtesy U.S. Department of State

Of course, not all special envoys bring the same mix of skills to their jobs, nor should they be expected to. Their tasks are often assigned on the basis of their background and talents—and the needs of a difficult set of circumstances. Asking an experienced disarmament negotiator to deal suddenly with human rights issues in Africa would probably not be the wisest use of his or her skills. Diplomats are nimble creatures, but not always that versatile.

That is where language training often comes in handy. It can be critical in understanding and dealing with the most complicated situations—such as the long-running Ukraine-Russia war—which is why FSOs are often tapped for the job. Since 1958, commissioned FSO’s have been required to demonstrate mastery of at least one foreign language as a prerequiste for promotion; many speak two or three fluently. And while it is relatively expensive to provide such training—six months to two years at a time—it is considered a good investment for a career which often spans 30 years or more.

With private citizens, of course, it is less likely that an envoy will come in armed with such fluency, especially in difficult languages like Russian. But asking Witkoff to step into Middle Eastern peace negotiations, where English was actually a good fit, was very nearly an inspired choice, in some ways, despite his complete lack of diplomatic experience or knowledge. Initially, he was pleasant but firm, unorthodox, and shook things up a bit. And he recently succeeded helping expedite the release of the last American hostage held by Hamas in Gaza, Edan Alexander.

And Witkoff has so far lucked out by being in the right place at the right time, at least in the Middle East. Even before he was sworn in, he was fortunate to serve in a rare bipartisan capacity alongside Brett McGurk, Biden’s outgoing envoy, in January 2025, and helped design the cease-fire and hostage exchange that eventually emerged. [See “Steve Witkoff: From property developer to global spotlight,” February 22, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/feb/22/steve-witkoff-trump-gaza-ukraine-envoy .]

But then his almost-accidental role in helping free Marc Fogel, an American imprisoned unfairly in Russia, gave Trump another idea—this one far from inspired, almost delusionary: involving him as the point man for peace negotiations to end the war between Ukraine and Russia. From the outset, he quickly betrayed his complete ignorance of the situation, soon alienating Ukraine’s leader, Volodomyr Zelensky, by parroting Russian talking points, and leading Zelensky to challenge the “disinformation space” allegedly inhabited by Trump.

It was the first step down a dark road leading to the famously nasty Oval Office showdown in late February, in which Trump and his bulldog, J. Dunderhead Vance, publicly ganged up on Zelensky for perceived impertinence, by asking too many questions. What little good, if any, Witkoff might have done since has been to tone down his rhetoric, somewhat. In the meantime, despite several invitations, he has still not visited Kyiv, only Moscow—a telling point.

* * * * * * *

Witkoff, originally a real estate lawyer, is certainly an intelligent man, and like Trump, his longtime friend, a successful wheeler-dealer. He became a billionaire as a property developer and investor, and uses his own private jet to fly wherever he wants. He is available, and willing, and trusts his intuition—but there his arsenal of useful tools sometimes seems to end. That is where even an intelligent man risks crossing the line into foolishness.

The language of high finance, back-room deals, and cronyism has very little bearing on the criminal seizure of one country’s territory by another, or on the kidnapping of thousands of Ukrainian children by Putin and his Nazi-like minions, or the deaths of hundreds of thousands of soldiers from both countries. It cries out for a more subtle mind, one able to assess the nuances of two very different positions—and somehow fashion a compromise that offers something of value to each. Not on caving in to the likes of Putin without even a squawk—and ignoring war crimes in favor of a dubious real estate settlement.

And of that particular gift—subtlety of understanding—Witkoff has not so far demonstrated much evidence. In dealing with Putin, Witkoff “seems to accept Putin’s word at face value,” William B. Taylor Jr., a longtime diplomat and former U.S. ambassador to Kyiv, told The Atlantic recently. “The Russians are very skilled and very devious. Witkoff has little experience with them, so he can be taken advantage of.”

Witkoff’s allies counter that say he is simply trying his hand at flattery, much as Trump often seeks to do. Ardent defender Lindsey Graham, the increasingly crude and senile senior senator from South Carolina, had vulgar words for his critics: “I would tell them all to fuck themselves,” the senator told The Atlantic. “To the foreign-policy elite, what the fuck have you done when it comes to Putin? How did your approach work?”

To his credit, Witkoff does not ignore advice from others, including former world leaders—after the fact. “After sensitive discussions abroad, he typically briefs some combination of the president, vice president, chief of staff, and national security adviser, among others. He has taken advice from a wide range of people, including intellectuals and former heads of state,” according to The Atlantic. [See “Trump’s real Secretary of State,” May 14, 2025, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2025/05/steve-witkoff-putin-russia-ukraine-diplomat/682805/ .]

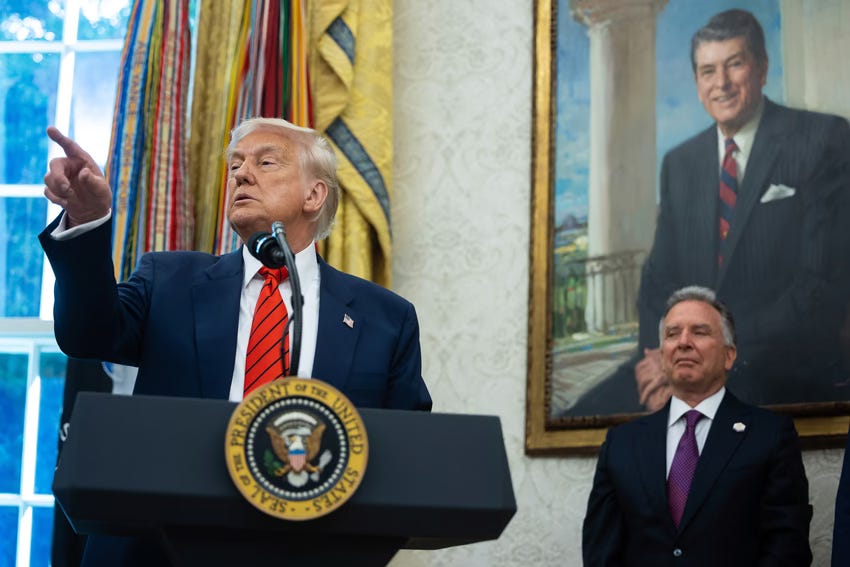

Trump and Witkoff at the White House, flanked by former President Reagan. Photo courtesy Politico.

Even setting Graham’s silly tirade aside, however, the newer “seat of his pants” approach practiced by Witkoff may augur even less well for the future than previous diplomatic forays.

In other words, negotiating with Russia has lately degenerated into a fool’s game—being played by a man many—especially in Russia—are now taking for little more than a fool.

Next time: More foreign affairs in a crazy, mixed-up world

Very interesting commentary, Ben. I haven’t had time to read your recent posts until today. I’ll try to read more of them :)