More foreign affairs in a crazy, mixed-up world

Update: Romanian election stunner; Caribbean leaders react to U.S. demands over Cuban medical brigade; Guyana faces Venezuela's brazen political incursion

The latest foreign policy scorecard shows one loss, one win, and a big question mark—a “draw,” if you will—for the Trump administration’s forays in Romania and the Caribbean.

The loss came in Romania’s presidential runoff on Sunday, in which a moderate, pro-EU and pro-Ukraine independent surged past the angry nationalism of a far-right candidate intent on carrying Trump’s MAGA banner into Eastern Europe, George Simion, who won the May 4 preliminary round with more than 40 percent.

Nicursor Dan, the next president of Romania. Photo courtesy Getty Images

Bucharest mayor Nicursor Dan, a long-shot independent who barely edged out the ruling coalition candidate in the May 4 preliminary round to make the runoff, pulled off the upset. Dan drew just over 54 percent of the final tally over Simion, who had bragged openly about his planned alliance with Trump—and like Trump in 2020, declared himself the winner before the vote was even counted. (Unlike his mentor, however, Simion later conceded defeat, when final results were announced.) [See “Pro-EU moderate Dan wins,” May 18, https://www.politico.eu/article/romanian-presidential-election-results-nicusor-dan-george-simion/ .]

Only Romania’s overseas diaspora—more than 1.5 million—showed a clear preference for Simion, voting for him roughly 55 to 45 percent, except in tiny neighboring Moldova, which had banned Simion from visiting for his incendiary statements, and where 87 percent of Romanians preferred Dan. But the 10 million domestic voters overwhelmingly favored the mild-mannered mathematician and reformist former member of Parliament.

The surprise victory further cements Romania’s somewhat fragile standing in both the EU and NATO—and is seen by many as a disappointing rebuke to Trump policies. Both Trump and his vice president, J. Dunderhead Vance, had bitterly criticized Romania’s constitutional court for annulling the outcome of the November election—won by a little-known right-wing professor, Calin Georgescu—citing intelligence reports linking the outcome to Russian interference in the campaign via TikTok videos on social media.

Georgescu was then banned from running again in the rescheduled elections—along with nearly a dozen other other characters—and his mantle was assumed by Simion, who favored ending military aid to Ukraine and merging Moldova with Romania, among other populist stands.

Once the celebration ends, the domestic political ramifications for Dan’s victory are far less clear. After he takes office by early June, his first task will be to cobble together a new government—probably only a minority coalition, vulnerable to early no-confidence votes—from among the badly-splintered eight-party political spectrum, plus a handful of independents and national minority representatives.

It will not be easy. His own former party—the Save Romania Union (SRU)—controls just 40 seats out of 330 in the lower Chamber of Deputies, compared to Simion’s Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR), second-largest party overall with 60 seats—but the AUR will not participate in any coalition, except perhaps with the off-the-wall SOS Romania party (23 seats), which is openly pro-Russia. Some observers pick current Acting President Ilie Bolojan (PNL), head of the Senate, as the next Prime Minister once Dan is sworn in.

None of the combative individual parties are natural allies. Recent events following the first round of elections May 4—in which the coalition candidate, Crin Antonescu, a former Senator and, briefly, acting president, placed a disappointing third—have only made difficult matters worse. The former “grand coalition” government—between left-wing Social Democrats (PSD), the country’s largest party, the lesser conservative National Liberals (PNL), and a smaller ethnic Hungarian party—collapsed in public rancor two weeks ago, after melding the single largest party for several years, by alternating prime ministers.

In an outbreak of vintage Romanian infighting, the PNL furiously turned on the PSD for not backing Antonescu enthusiastically enough, forcing the resignation of Prime Minister Marcel Ciolacu—who had lost badly in the previous presidential election— from both his PSD party and the parliament.

Resolving the fractious atmosphere cannot come a moment too soon. Romania has been almost leaderless for months. It has been without a president since mid-February, when Klaus Iohannis resigned after a tumultuous 10-year term.

But at least Ukraine and Moldova can breathe a collective sign of relief as Dan prepares to take charge. And the twin dunces of U.S. foreign policy, Trump and Vance can continue to fume over the failure of MAGA to take root in fertile Carpathian soil.

A page back in time ... is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work,

consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

* * * * * * *

The big “win” for Trump came when Bahamian Prime Minister Philip Davis pledged to overhaul the system it uses to pay Cuban medical personnel serving on contract in his island nation. The announcement was not altogether unexpected—Davis had earlier expressed willingness to revise the scheme if his investigation bore out charges by the U.S. Secretary of State that the Cuban government was illegally “trafficking” its nurses and doctors by pocketing most of the wages paid for their services by host governments.

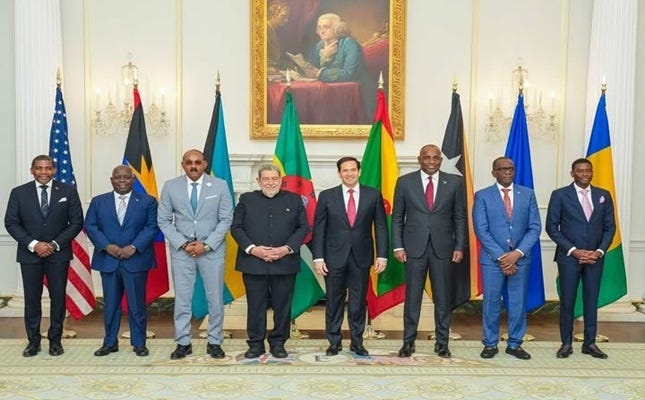

Davis was among seven Caribbean leaders (the rest from the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States, or OECS) to visit Miniscule Marco in Washington earlier in May to discuss regional issues, including the Cuban medical brigade and the expected effects of U.S. tariffs. Most other Caricom and OECS leaders have not yet made such concessions on the Cuban issue, some openly bristling at Marco-inspired threats to revoke their visitor visas to the United States if they failed to comply.

Marco, who detests all things Cuban despite his own familial links, has been pushing the trafficking issue since his time in the U.S. Senate.

Leaders of OECS nations and Bahamas meet Rubio in Washington. Public domain photo

Davis, among the most conciliatory leaders on the issue, has publicly suggested that The Bahamas would now begin to pay Cuban medical personnel directly, rather than remitting the amounts Cuba had previously charged to accounts held by the Cuban government. The Bahamas is the first Caribbean Community (Caricom) nation to agree to such a controversial revision—long demanded by Rubio as the price for remaining in the good graces of the United States.

Others, led by Barbados and Jamaica, have instead defended the longstanding practice, claiming that the medical personnel sent by Cuba are treated fairly, seem happy, and are paid prevailing wages. They point out that they cannot easily replace the well-trained doctors and nurses, popular providers on whom their citizens have come to depend—especially when Caribbean-trained medical personnel are often lured to the United States and other Western countries by higher salaries there.

“What I can say to you is that we are in the process of renegotiating all these memorandums of understanding for labor out of Cuba, just like we are doing with other countries like the Philippines, where we have a number of foreign workers. That is not an unknown concept or construct. But now that concept is now being looked at as an ingredient for forced labor. So, we will address that. Anyone we hire, we will say, look, we will pay you directly into your account,” Davis told local media on his return from Washington.

Phillip Davis, prime minister of The Bahamas. Public domain photo

[See “Bahamas bows to Trump,” May 12, https://www.caribbeanlife.com/bahamas-bows-to-trump-on-cuban-medics-changes-to-pay-system/ .]

Whether Davis remains an outlier or becomes the leader of a developing vanguard remains to be seen. Prime Minister Gaston Browne of Antigua and Barbuda, who traveled to Washington, took pains later to defend the fairness of the program, claiming “We are not involved in any form of human trafficking … In fact, the Cuban nurses and doctors here are probably better compensated than many of our local practitioners, once you factor in free housing, utilities, and other benefits.”

Caricom’s leader, Mia Amor Mottley, Prime Minister of Barbados, views the Rubio initiative as pure bullying; she has said she was perfectly willing to give up her U.S. visa if it came to that.

Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness, up for reelection this summer, has also defended the program, noting that more than 400 Cuban medical practitioners are currently under contract in Jamaica, providing a lifeline to the island’s 2.8 million residents. Neither he nor Mottley attended the Washington mini-summit, although both met with Rubio during his recent visit to Kingston, Jamaica.

* * * * * * *

As a “reformed” Foreign Service Officer—I walked away from the U.S. State Department in 1997, after serving roughly 15 years—I keep my eyes out for unusual and outrageous events occurring in countries of interest to the United States, particularly those I have served in or visited. This often includes analyses of U.S. actions affecting those countries, whether wise or effective—or puzzling, as here—and in some cases, simply mind-boggling. (Note: I have never served in either Venezuela or Guyana, although I spent two years next door in Paramaribo, Suriname.)

The “question mark” looms over U.S. policy planners as Guyana—the South American nation Miniscule Marco visited after leaving Jamaica—awaits a difficult reckoning next week with its adversary neighbor, Venezuela—another country which the Trump administration has gone out of its way to alienate since taking office in January. Venezuela is determined to hold a sham election on May 25 to justify the on-paper annexation, at least, of two-thirds of Guyanese territory—with absolutely no legal justification—after which Guyana may then decide, justifiably, to call on its new ally, the United States, to protect its interests.

The United States is currently cultivating Guyana and its leader, President Mohamed Irfaan Ali. During his recent visit, Miniscule Marco boasted of signing a military agreement to defend Guyana if its territory or offshore oil drilling zones were invaded by Venezuela. U.S. naval vessels soon began conducting joint military exercises with the Guyanese military to ward off possible unfriendly attacks by Venezuelan vessels.

The rather complicated related scenario now unfolding along the Venezuela-Guyana border involves the disputed Guyanese region of Essequibo, a Florida-sized chunk of land west of the Essequibo River that nominally belongs to Guyana—awarded to it by an international tribunal in 1899—but which Venezuela has long claimed belongs to it instead. The region covers about two-thirds of the entire nation of Guyana, including half of its exclusive economic zone in the sea and offshore oilfields now being developed jointly with Exxon—the real reason, apparently, for the land-grab.

After a UN-led group failed to resolve the long-running Essequibo ownership matter in 2018, the dispute over who should “own” the territory is currently being adjudicated by the International Court of Justice, whose authority over the matter Venezuela refuses to recognize. It is not expected to rule before 2026. Guyana has decline to resume bilateral talks until after the ICJ rules, and in March, asked the ICJ to call out Venezuela for its impatience and unfriendly actions in the meantime.

A map of the controversial new Venezuelan “state” of Guayana Esequiba. Courtesy CrisisGroup.com

Bilateral talks had resulted in the Argyle Declaration in December 2023—thought to have calmed things down, at least—under which the two nations agreed, along with regional co-signers and the UN, not to escalate the dispute and to set up a joint commission to address it. But the situation has instead begun to deteriorate again.

According to the nonprofit Crisis Group, Venezuela has begun making serious plans to “annex” the region, in order to stake a claim to the offshore oil zone now legally controlled by Guyana. In 2024, Venezuela’s “government-controlled National Assembly approved the creation of the new state [Guayana Esequiba], covering Essequibo itself and one Venezuelan border municipality, Sifontes.” [See “Venezuela presses territorial claims,” April 8, https://www.crisisgroup.org/latin-america-caribbean/andes/venezuela-guyana/venezuela-presses-territorial-claims-dispute-guyana-heats .]

The next step, according to the Crisis Group analysis, is conducting a spurious election—set for May 25—in the new “state,” almost none of whose territory Venezuela currently controls, “to elect a governor and eight National Assembly deputies to represent the newly created state of Guayana Esequiba … Venezuela’s National Electoral Council has yet to clarify who will vote and how. There is no electoral register for the new state, and some experts have suggested that Venezuelan voters as a whole might be invited to cast votes on behalf of the new state.”

Infuriated by the challenge, Guyana has forbidden any of its citizens from taking part, on pains of being charged with treason. Just over 100,000 people live in Essequibo Region—about one-seventh of Guyana’s population, most of them English-speaking, like almost all Guyanese citizens—according to a report by the Observer Research Foundation. [See “The Venezuela-Guyana Dispute,” January 2024, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/the-venezuela-guyana-dispute-a-storm-in-a-teacup .]

Venezuela’s recent history of refusing to document its electoral results makes the sham election almost laughably impractical; it has no infrastructure allowing it to hold or supervise such an election in the immense region, most of which is only accessible by boat or plane, and much less to recruit and use local personnel to count ballots. While the two countries still maintain full diplomatic relations and operate embassies in each other’s capitals, Venezuelan passport-holders must also hold a valid visit before entering Guyana—unlikely to be issued in the current atmosphere.

Map of Venezuela, Guyana, and disputed Essequibo Region. Courtesy Newsweek.com

How the U.S. government will respond immediately to the sham election is anyone’s guess. Its navy may well step up patrols in the offshore oilfield area, although sending U.S. ground troops into the Essequibo Region—to ward off invaders from the west—is an almost unthinkable option, comparable to a fantasy scenario straight out of Doctor Strangelove.

But the likelihood of a shooting encounter with Venezuelan naval vessels in the offshore oilfields—once deemed a virtual impossibility—could increase exponentially, once Venezuela announces that it has begun the actual annexation process, in open defiance of international law and the terms of the expected ICJ ruling.

How Miniscule Marco and the State Department will react immediately is anybody’s guess—probably with big talk and very little action. U.S. sanctions against Venezuela have done little so far to restrain its increasingly belligerent actions. Perhaps it will prod the Organization of American States—from which Venezuela attempted to withdraw in 2017, then changed its mind, and which has frequently criticized it for human rights violations—to take punitive action against the transgressor. Big deal.

Under disputed President Nicolas Maduro, Venezuela has proved, time and time again, that it does not care what the rest of the world thinks—and it will continue to thumb its nose and sell its oil to anyone who will buy it, sanctions or no sanctions. It has grudgingly accepted hundreds of U.S. deportees in recent months, ‘tho it is unlikely to accept anything like the 300,000-plus who now stand to lose Temporary Protected Status as asylum-seekers, now that the Supreme Court has allowed Trump to end that status.

But if and when that ICJ ruling comes, enforcing it will pose a very real moral dilemma for the United States, which has declined for almost 40 years to accept the jurisdiction of the ICJ—for political reasons—despite its 1946 pledge as a founding UN member to abide by its rulings.

The 1986 withdrawal stems from an ICJ ruling directing it to pay damages to the then-Sandinista-led government of Nicaragua. In Nicaragua v. United States, the court ruled (with only the American judge dissenting) that the United States was “in breach of its obligation under the Treaty of Friendship with Nicaragua not to use force against Nicaragua” and ordered the United States to pay war reparations, which it has never done.

Next time: More foreign affairs in a crazy, mixed-up world