More foreign affairs in a crazy, mixed-up world

Surinamese election a cliffhanger, as opposition edges Santokhi's ruling party

Election Day 2025 struck South America’s smallest country Sunday like an indecisive monsoon—a virtual tie between the corrupt ghost of the past and the promising oil wealth of the future.

The opposition NDP party of fugitive former dictator Desi Bouterse, who died in disgrace in December, held the slight upper hand in preliminary results, with 18 of Suriname’s parliamentary seats, leading party chairman Jennifer Geerlings-Simons to declare herself jubilantly as the early winner.

Not so fast, Jennifer Simons—the vote ain’t over. Courtesy US News and World Report

But President Chan Santokhi, whose ruling coalition may or may not eke out first place in the final call, appeared to claim either 17 or 18 seats—by about 2,000 to 4,000 votes—but down 10 percent from the 20 seats his VHP reform party won in 2020. Negotiations with a smaller third party, the ABOP, in 2020 vaulted Santokhi into the presidency.

The inked finger’s the thing for President Santokhi—maybe. Courtesy France 24

Another 16 seats were apparently won by smaller parties, including Vice President Ronnie Brunswijk’s ABOP, which took home eight seats in 2020 and earned him the nation’s second highest spot in backroom negotiations.

Initial reports from Reuters did not include the count for ABOP or any other party from Sunday’s vote. With a few dozen polling stations yet to be counted—perhaps fewer than 10,000 votes yet to be tallied—turnout in Suriname was nearing 60 percent of the country’s 400,000 voters at the close of polling, with final results expected by Tuesday.

According to Reuters, “With 43 polling stations yet to be counted, results showed the opposition National Democratic Party (NDP)—founded by former President Desi Bouterse, who dominated Surinamese politics for decades … —had won 18 seats, with 79,544 votes. The ruling Progressive Reform Party (VHP) of current President Chan Santokhi won 17 seats, with 75,983.” [See “Suriname’s ruling party, opposition nearly tied,” May 26, https://www.reuters.com/world/surinames-ruling-party-opposition-nearly-tied-parliamentary-election-2025-05-26/ .]

But a later regional report, posted by the Daily Herald of St. Maarten, saw the parties in a virtual tie: “At midnight Sunday, NDP had 62,286 votes, which represented a tiny advantage over VHP’s 61,577 votes. … It is clear that neither party will achieve this majority on its own, but together NDP and VHP have 36 seats, more than enough to elect a president without support from other parties.

“The other option would be that NDP or VHP would try to form a quilt-like coalition with multiple parties that won less seats: NPS 6, ABOP 5, PL 2, A20 1 and BEP 1.

Sunday’s elections have been billed as a turnaround point for the country. On the one hand the electorate appeared quite done with President Santokhi whose tenure was marked by a runaway foreign exchange market and complaints about nepotism. Characteristic in this is the blow voters dealt to his vice president Ronny Brunswijk, a former guerilla leader turned gold miner whose ABOP Party saw a drop from 8 to 5 seats.

[See “Suriname elections: President Santokhi’s VHP toe-to-toe with NDP,” May 26, https://www.thedailyherald.sx/islands/suriname-elections-president-santokhi-s-vhp-toe-to-toe-with-ndp-candidate-geerlings-simons .]

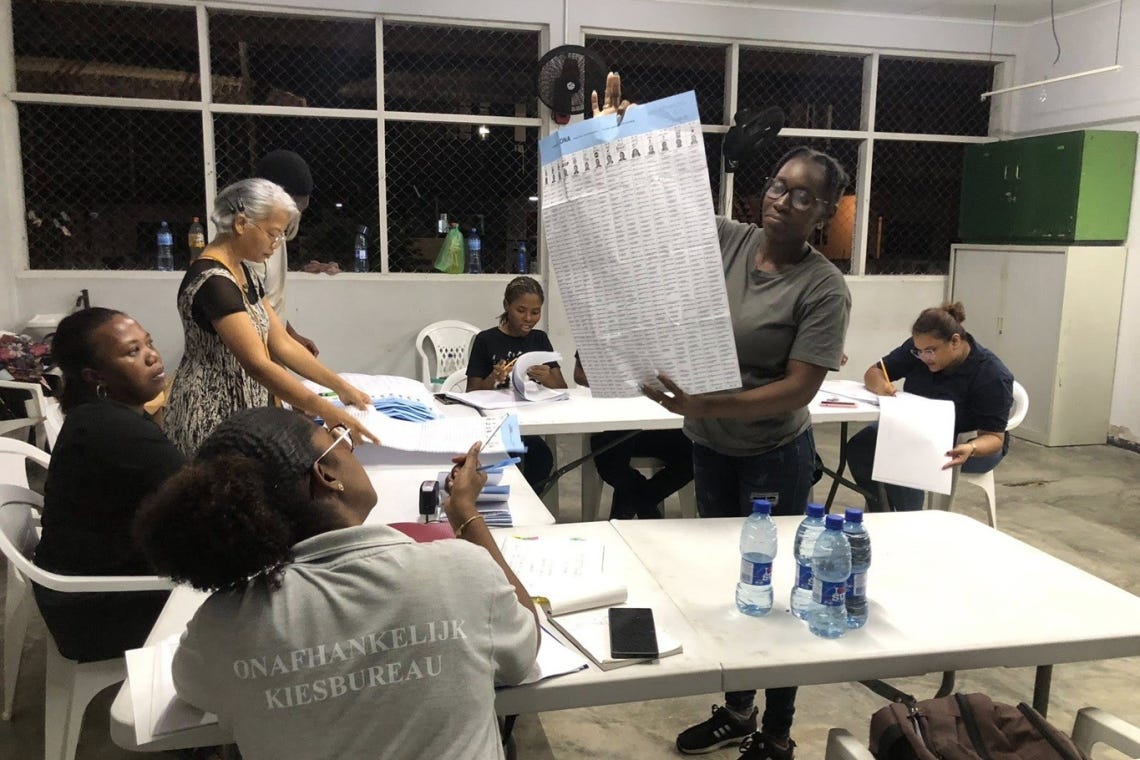

Surinamese poll workers burn midnight oil after Sunday’s elections. Courtesy Daily Herald

A page back in time ... is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work,

consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

* * * * * *

As a “reformed” Foreign Service Officer—I walked away from the U.S. State Department in 1997—I keep my eyes out for unusual and outrageous events occurring in countries of interest to the United States, particularly those I have served in or visited. This often includes analyses of U.S. actions affecting those countries, whether wise or effective—or neither, as here—and in many recent cases, more puzzling than practical.

I served at the U.S. Embassy in Paramaribo for two years, 1989-1990, and found the political situation astoundingly inept back then. Since dictator Bouterse stepped down as leader in 1987, when his party lost control of the National Assembly, the country had been dominated by a weak, ineffective and only nominally democratic government—with Bouterse continuing to control the strings as head of the military, even deposing one elected prresident by telephone in 1990.

Bouterse is finally out of the picture, and mourned by few, but his party—which won a complete majority in the National Assembly in 2015, before dropping back badly in 2020—is resurgent after his death. From 2010 to 2020, when he was president, U.S. relations with the Surinamese government were less than productive, at best.

For decades, the United States has had little leverage, at least until the Santokhi presidency—and the recent discovery of offshore oil fields that promise to make nearly-bankrupt Suriname into a far wealthier nation almost overnight. Recent inroads by China in both Suriname and neighboring Guyana—with hundreds of millions of dollars in foreign development assistance, matched by nothing at all from America—have set off alarms in Washington, forcing Secretary of State Marco Rubio to make an unusual flying visit to both countries in March.

In front of cameras, he preened but promised little, in fact—mainly warning Suriname to avoid Chinese telecommunications infrastructure, which would complicate possible investments by U.S. companies in the country—hoping to prop up the foundering U.S.-friendly Santokhi regime, at least.

Whatever the outcome of this election, Miniscule Marco’s visit will almost certainly be seen by observers on both sides as a factor, positive or negative—either helping resurrect Santokhi’s flagging hopes after dismal recent polls, or spurring NDP voters bent on restoring the fading legacy of spendthrift former president Bouterse, who drove the country into bankruptcy in his second term.

Marco had no time to talk politics during his brief airport meeting with Santokhi—and judging by his limited understanding of domestic developments in any of the Caribbean countries, it is just as well. The conversation would have been embarrassing, and pointless. For despite his pretended mastery of foreign affairs during his otherwise-mediocre terms in the U.S. Senate, he has failed to grasp even a minimal understanding of real life under a parliamentary government—even a corrupt government such as Suriname, which he understands and thinks he can deal with.

Minisicule Marco certainly has no substantive appreciation of the effects of unfair foreign tariffs on Caribbean countries with which the United States already enjoys a positive trade balance. I doubt he could name even the two major parties in Suriname, much less the wide variety of parties contesting these elections—although, to be fair, almost no nin-Dutch-speaking outsider could do it, either.

According to a pre-election summary in Caribbean Life, a dozen parties were seeking seats, including the “National Party of Suriname (NPS) led by former cabinet minister Greg Rusland and a key player leading up to independence in 1975, … and Pertjajah Luhur (PL), which targets the votes of Surinamese of Indonesian-Javanese descent,” plus a scattering of tiny groups which will probably not receive enough votes to enter the parliament. [See “Suriname votes Sunday,” May 21, https://www.caribbeanlife.com/suriname-votes-sunday/ .]

The much-smaller NPS and PL had once joined Santokhi’s coalition wi ABOP in 2020, but the NPS dropped out in 2023 after internal friction developed over charges of corruption and other issues.

Brunswijk, the ABOP kingmaker in the last two elections—siding with Bouterse’s NDP in 2015 and Santokhi’s VHP in 2020—remains a troublesome question mark: a convicted felon (drug smggling charges in The Netherlands, in absentia) unable to travel widely outside Suriname, and far from the good graces of the NDP. After being spurned by NDP party leaders leading Bouterse’s funeral in early January, he then resorted to puzzlingly personal criticism of former First Lady Ingrid Bouterse-Waldring, a possible candidate for president after the new parlament is sworn in’.

If this ABOP parliamentary share does drop to five seats, as now seems likely, he will have far less leverage in the negotiations—and will almost certainly not continue as vice president under the next government. One or the other main party will probably be able to piece together 26 votes, thus controlling parliament—but a grand VHP-NDP coalition for president is almost inconceivable, given the fractured state and historical animosity of Surinamese politics.

Electing the president is the first task awaiting the new National Assembly, requiring a two-thirds majority—or 34 votes—and prospects are dismal at best. Cobbling together 34 votes under the current photo-finish lineup would require political cooperation not seen in Paramaribo for decades—and may trigger the so-called “poison-pill” provision of the constitution.

After two unsuccessful presidential votes, an extra-parliamentary People's Assembly must be formed from all National Assembly delegates and regional and municipal reprsentatives elected by popular vote in the most recent national election.

Stay turned for the latest confusing results from Paramaribo.

Next time: African Americans join the nation’s political game: Introduction, 1864

Thanks, Ben. Inept would be a polite word for our foreign relations these days.