Life on the open road in the Dakotas

Part 4: Don’t sell Bismarck short—and be sure to visit Teddy Roosevelt, back to life in Medora!

Bismarck is a little-known gem of a city—not terribly large at 75,000 today, in a metropolitan area of nearly twice that, including its sister city, Mandan, on the other bank of the Missouri River. It has been growing fast in recent years, up from about 55,000 when I visited it for a week in 2003. The North Dakota capital is only the second largest city in the state—after Fargo, which has a far more familiar name because of the eponymous, popular film from the 1990s and the long-running TV series it inspired.

Bismarck’s name may not carry the same cachet, but it is actually a more interesting place than one might expect. For one, it is the only state capital named for a foreign statesman—the Iron Chancellor Prussia and then unified Germany, Otto von Bismarck (1815-1899)—and was intended to have exactly the effect it did: attract German-speaking immigrants in the 1870s to a vast and sparsely-populated new territory (it became a state in 1889). (The 1960 movie Sink the Bismarck!—recounting the Allied WWII attack on the mammoth German battleship— and the Johnny Horton song of the same year gave the city’s name a whole new dimension of meaning!)

Even today, more than half of the city’s residents still claim descent from German settlers, even more than the top-ranked major city on most U.S. lists (Milwaukee, which boasts more than a third of its residents as German in heritage).

The 19-story Art Deco state capitol in Bismarck, built in 1934. Photo courtesy Bobak Ha’Eri.

You can hardly go anywhere in Bismarck without catching sight of the much-revered state capitol, a 19-story Art Deco structure built in 1934, at the height of the Great Depression, to replace the former building, which burned down in 1930. At 242 feet in height, it is still the tallest building in the state. (Only one other building in Bismarck is even half as tall at 125 feet, a former hotel, the Patterson, built in 1910, since converted into senior apartment housing.)

The building is well worth the almost-obligatory public tour, just to be able to look at the low-rise city, without skyscrapers, from a bird’s-eye-view on the top floor. North Dakotans are justifiably proud of their capital city, which looks clean to tourists and is admirably well-kept—and not surprisingly, proud of their identity as the Peace Garden State.

I did not have the time to travel 200 miles to the International Peace Garden—which sits on the border with Canada’s Manitoba Province, north of Minot, and which since 1932, has symbolized the uninterrupted era of peace between the United States and its northern neighbor. But I would have liked to …

That is the state’s official nickname, on its license plates since 1957, despite attempts to change it to an almost-as-popular “Rough Rider State” (honoring North Dakota’s famous adopted so, Teddy Roosevelt—or the Flickertail State, in honor of a variety of ground squirrel that seems to inhabit the wide open spaces between its few cities.

By and large, North Dakotans are also affable and friendly; visiting their state is like walking into their common living room. You just feel welcome, like an old friend. When the state’s GED Administrator, Assistant State Superintendent of Public Instruction G. David Massey, offered Bismarck as a site for the GEDTS annual meeting meeting, I remember a few eyebrows were raised at first at the thought, but it turned out to be a wonderful site in the end—and nearly 200 hundred attendees agreed.

* * * * * *

A little background on the GED Testing Program: In 2003, it was an international partnership involving the GED Testing Service, each of the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia, the Canadian jurisdictions, the U.S. territories, and the U.S. military. The GED Testing Service was still part of the American Council on Education, a private, nonprofit organization in Washington, D.C.; we developed and delivered the GED Tests and established the test administration standards.

All U.S. and participating Canadian jurisdictions then administered the GED Tests and awarded their high school credentials to adults who passed all five of the GED Tests and met the average score requirement across the five tests. In total, the jurisdictions operated more than 3,000 Official GED Testing Centers worldwide, where adults could take the GED Tests throughout the year; most centers offered them at least once a week, and almost all at least once a month.

The GED Tests were initially developed in 1942, at the request of the U.S. military, to help returning World War II veterans finish their studies and reenter civilian life. The GED Tests then became available to civilians in 1947, when the state of New York implemented a program to award its high school diploma to those who passed the tests. California became the last state to join the GED Testing Program in 1973.

Between 1942 and 2003, the GED Testing Program had already served as a bridge to further education and employment for more than 15 million people.

That’s the official version, anyway. In reality, the GED Tests had accomplished so much more: changing people’s lives in a more practical fashion by removing the stigma of high school dropout from their permanent records, and giving both disadvantaged teenagers (over 16) and their grandparents alike confidence in their ability to learn and be even more useful citizens.

Anyone who worked in the GED Testing Program could tell you dozens of stories about the effect that new high school diploma-equivalent had on their self-esteem, not to mention their paychecks. It made you feel good to work there.

The annual conference gave the folks who worked there a chance to compare notes with colleagues from other states, territories, and Canada, to see how they might improve their own programs at home. There were workshops, speeches, endless meetings—but it was also a chance to have a lot of fun sightseeing and making new friends.

Since joining GEDTS in 2000, I had been to two other annual conferences—in Charleston, S.C., one of my favorite cities, and Boston, my first visit there. Both were delightful, exciting trips. But Bismarck had a slightly more genuine feel to it—as if it were not trying to prove anything, just make you feel at home and hope you would come back for more.

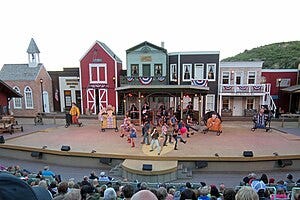

Toward the end of the conference, we were offered a sort of field trip—to the western village of Medora, about a 2-hour bus trip away, close to the Montana border, to see the Medora Musical. It sounded kinda corny, but about 40 of us signed up, just for fun. It turned out to be one of the most pleasant outdoor entertainment events I had ever been talked into.

Outdoor dramas and musicals are generally a mixed bag. Some epic dramas, like “The Lost Colony” in North Carolina’s Manteo (since 1937), or “Unto These Hills” in Cherokee (1950), have been drawing enthusiastic crowds for nearly a century, with little signs of slowing down. Others come and go, as the novelty wears off, especially musicals with no romantic theme or memorable songs. But the Medora Musical—originally titled “Old Four-Eyes,” then briefly, “Teddy Roosevelt Rides Again!”—first opened in 1958, to commemorate TR’s 100th birthday, and after a few fits and starts, is still drawing record crowds after more than 60 years.

More than 4 million people have paid so far to see the live-action summertime-only musical, set in a staged version of the tiny town’s (population 121) downtown area, around the restored Rough Rider Hotel. Nothing thrilling, mind you, just some very good singers and dancers and a few fake gunshots thrown in—with the star of the show being a very young version of the nation’s 26th president, who lived and ranched for several years in Medora while mourning the death of his beloved first wife in the early 1880s.

The stage at the rollicking Medora Musical, sen here in 2014. Photo courtesy Michael Holley

The Burning Hills amphitheatre, carved into a butte near the town, seats 2,800 guests, each one with a grand view of the Theodore Roosevelt National Park! It’s a spirited evening of fun—with a little history thrown in—and you leave with a smile on your face and a wish, somehow, you could have lived there when TR did—or even when he returned as President in 1903 (see http://www.mandanhistory.org/areahistory/1903trvisittondak.htm ).

The Mandan Historical Society recalls that presidential visit this way:

The final destination on April 7th was a half-hour stop in Medora. Arriving after dark, Roosevelt later recalled that “the entire population of the Badlands down to the smallest baby had gathered to meet me… They all felt I was their man, their old friend; and even if they had been hostile to me in the old days when we were divided by the sinister bickering and jealousies and hatreds of all frontier communities, they now firmly believed they had always been my staunch friends and admirers." Roosevelt continued, “I shook hands with them all and…I only regretted that I could not spend three hours with them."

A few of TR’s old friends welcomed him back to Medora in 1903. Photo courtesy Mandan Historical Society

The business district of Medora, pop. 121, has a remarkable number of summer visitors. Photo courtesy Andrew Filer

Going back to Bismarck late that night, I did not have time to so the kind of thing any historian would normally do—stop off for a visit at the TR Center at Dickinson State University—maybe someday, I thought?

But you and I can still visit their website—at www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org — “to view films in which Theodore Roosevelt makes an appearance, listen to audio recordings that feature his famous falsetto voice, and read letters, diaries, and newspapers by and about Roosevelt. The staff at the Theodore Roosevelt Center welcome visitors to learn about Theodore Roosevelt's time in North Dakota and about the work to preserve and promote Roosevelt's legacy.”

And sometime after 2026, when I may just go back, the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library will open just down the road from Medora. (Ground was broken just this year, after a $200 million fundraising campaign.) Now there’s a great reason for another road trip!

Then it was time to head back to the East Coast—and reality, of sorts. Sigh ….

Next time: Remembering a cub reporter’s days in the newspaper game