Life on the open road in the Dakotas: My visit to the Badlands and Medora, buffalo and all …

Part 1: Starting it off with a speech in Sioux Falls

It was the summer of 2003, and I was about to make my first trip to South Dakota’s largest city: Sioux Falls, on the Big Sioux River, county seat of Minnehaha County. My purpose was to deliver a speech to recent adult graduates of South Dakota’s GED Testing program at the Southeast Technology Center at Southeast Technical College—a two-year public institution of higher learning. They were a small but enthusiastic group of students, many in their 60s and 70s, who had finally achieved the milestone so many others take for granted. At least one of them was a World War II veteran, then in his early 80s.

And it was a lot of fun. I did not stay long—just one night— but got a reasonably good grasp of the surroundings and the situation. South Dakotans are generally better educated than the average American—only about 9 percent of the state’s adult citizens lack a high school diploma, according to recent statistics, compared to about 13 percent in the US overall—and South Dakota is committed to reducing the level even more. So the graduates I met seemed genuinely proud of finally earning a high-school equivalency certificate. A few even intended to continue their education at Southeast—perhaps to earn an associate’s degree, one of the reasons most had enrolled in the test preparation program in the first place.

At the time, I was serving as special projects director for the GED Testing Service in Washington, D.C., then a not-for-profit arm of the American Council on Education membership association. The GEDTS executive director and her four directors took turns speaking at graduation ceremonies around the country, and then once a year, convened a conference of state directors of adult education to discuss issues of general interest, as well as ways to promote the test and encourage more non-graduates to prepare for it and take it. The test has been around since the U.S. military first began encouraging draftees to finish their high school education in 1942, and up to 20 million adults have used the GED Tests to do that since. (To the uninitiated, GED used to stand for “General Educational Development”—as Merriam Webster defines it—but “general education diploma,” their pointless second definition, is way off base …)

The GEDTS has since become a public-private partnership with testing giant Pearson. Back then, we developed, edited, and marketed the test ourselves. Except in very limited circumstances, we did not administer the test, which was carried out at state-run testing centers run by adult education programs across the country.

That year’s summer conference was being held about a week later in Bismarck, North Dakota, so when South Dakota sent in a request for a commencement speaker, I volunteered to fly out to Sioux Falls, then rent a car and drive the rest of the way to Bismarck, with vacation stops at Mount Rushmore (Rapid City) and Pierre, the state capital. It would be about 850 miles total, spread out over five days, and would give me the rare opportunity to see the Badlands up close.

Sioux Falls itself was an interesting, picturesque city, formed around Fort Dakota in the 1850s, hugging the cascades of the Big Sioux River. While it is still not large by Eastern standards, in 2003 it boasted a population of more 100,000, or roughly one-seventh of the rural state’s population. (Today, at about 200,000 residents, it is now home to almost a quarter of the state’s citizens.) It is often confused with its nearest competitor—Sioux City, Iowa, about 75 miles to the south and slightly smaller in size—and not just by presidential candidates suffering from jet lag (or worse).

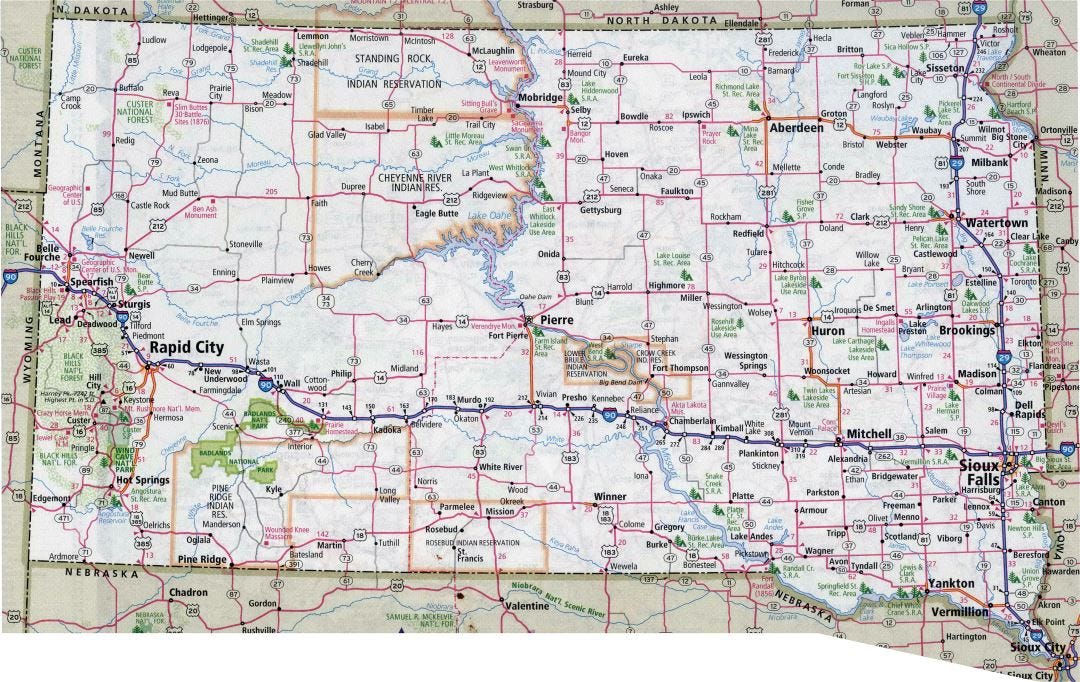

Skyline of Sioux Falls, South Dakota, today, as seen from Falls Park. Public domain photo

Sioux Falls sits in the state’s southeast corner, far closer to the state’s borders with Minnesota (24 miles away), or with Iowa (10 miles), and even Nebraska (70 miles) than with most of South Dakota—which meets Iowa and Nebraska at Sioux City. And as a consequence of its geographic position, Sioux Falls is the only city in the state crossed by two Interstate highways—I-90 heads west to Rapid City, the state’s second-largest urban area, and beyond into Wyoming, and east to Rochester, Minnesota, while I-29 heads north to Watertown and beyond, to Fargo, North Dakota, just below Canada’s Manitoba Province.

South Dakota road map. Public domain illustration, courtesy of https://www.maps-of-the-usa.com/

South Dakota may be one of the smallest U.S. states in population—still fewer than a million residents in the 2020 census (just behind Delaware)—but is in the top third of states by land area, at 77,000 square miles. Driving across South Dakota, as I soon learned, is not difficult in the summer, especially on the Interstates, but still a bit lonely. But it is refreshingly vast, and largely empty. In some places, I saw only a handful of cars for long stretches, and as I entered the Badlands, far more buffalo than people—or, as the Smithsonian would chastise me for misspeaking, I saw more (American) bison than Americans. Yet the prospect was not at all worrisome to me.

Rapid City, South Dakota’s second-largest city. Public domain photo

For now, I was at home, almost alone, on the open road for more than 400 miles between Sioux Falls and Rapid City. My one-way rental car was reasonably comfortable, if outrageously overpriced—a small Ford station wagon, as I recall—and I found a couple of reasonably good radio stations to listen to as I drove.

It was a delightful change to be away from the Washington, D.C., metro area—among my least favorite urban areas in the country, mainly because of the crowds everywhere, the snarled traffic, and the incredibly rude drivers. Maybe even in the world.

I should note here that I grew up as a small-town boy in a very rural part of eastern North Carolina, and by the time I left to join the Foreign Service in 1983, had already learned to detest heavy traffic. I endured it by trying to ignore it and concentrate on the rhythm of driving, getting into the Zen of it. Like my Daddy before me, driving gave me time to think—in even bouts of swearing at the fools who took chances, or between cursing the inventors of recreational vehicles and mile-long transfer trucks.

As a child, I had already ridden thousands of miles across the country several times with my family—parents, older brother, and younger sister—on vacations to visit my grandparents in Utah, where Daddy grew up, or Texas, where Mother’s sister now lived. Memorable trips, seeing America from the ground up, stopping when we wanted to (or had to). I was still too young to drive myself on the last trip we took, when I was 15, but it would still have been Daddy behind the wheel, regardless. (He never even let Mother, a very good driver, take the wheel on those journeys—it was his job, and he would not share it!—but mostly because he literally hated being a passenger in anyone’s car.)

Small wonder I did not board a commercial airplane until I was out of college—when I wanted to go to Norway for a vacation … before that, I flew in small planes occasionally, and loved it, but there was no thrill comparable to driving a car …

Not surprisingly, I developed an unquenchable love for watching rural landscapes go by, even at 80 miles an hour (on the Kansas Turnpike—where it felt as if our family car were floating). My penchant for memorable long drives survived in both my marriages, including a 500-plus-mile California coastline drive in 1975, from San Diego to Sausalito, followed by a trip across central Utah to visit my grandmother, and a decade later, across Western Europe—Copenhagen to Madrid, roundtrip, 6,000 kilometers all told! (And even shared driving duties on both trips…) I took the train or drove anywhere I could, rather than fly …

California’s coast was magnificent in 1975—and the drive spectacular! Public domain map

Copenhagen to Madrid and back again—6,000 kilometers on the (European )road in 1986! Public domain map

I had always wanted to see Mount Rushmore—another lifelong obsession born from watching North by Northwest too many times, I suppose. I doubted I would actually get to walk along the pathways above the presidential faces, as Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint did—even if I did, I have this thing about heights, anyway—but just seeing them from a distance would suffice. And seeing herds of bison on the prairie just made the whole idea a win-win, in my book.

Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint with larger-than-life friend in background. Photo courtesy Britannica.com

From there, I would head over to Pierre—South Dakota’s tiny capital—and then up to Bismarck, rejoining my staff and colleagues for the summer convention. Who could ask for anything more? My wife did not accompany me on this trip, but stayed in Alexandria with the dogs; a former flight attendant, she still loves to fly and drives only if absolutely necessary. After the first 250 miles, the Zen of long automobile trips is soon lost on her …

Next time: Rapid City, Crazy Horse, and all that …