Ida B. Wells and the perils of paving over historical potholes

Documentaries with omissions only another historian might even notice

As Black History Month wound down in February, I found myself watching an interesting documentary on PBS the other night on the life of Ida B. Wells-Barnett, the crusading Chicago journalist of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Called Ida B. Wells: A Chicago Stories Special, it was engaging, well-written, and held my interest for almost all of the full hour it ran on a Florida PBS station.

But at the very end, I found myself annoyed at one glaring, to me, omission of fact—her long involvement in the National Afro-American Council, which I have written extensively about. I was curious as to why the film chose to leap-frog over about 10 years of her life, and her political activities during that period.

What was in the documentary was all true enough, timely, appealing. But what was missing—and I think, of almost critical relevance to the antilynching crusade she led—lay beneath this paved-over “pothole.” Facts that held a very strong relevance for anyone interested in understanding Ida Wells and her lifelong quest against lynching. Things only another historian might notice … As a historical purist—a biographer and writer who lives for balance and reasonable objectivity, the whole story, in other words—it rankled my sense of fairness and completeness.

It involves the selective editing of African American history around the turn of the century to suit a certain retrospective narrative, downplaying or ignoring the presence of any uncomfortable or inconvenient characters—of either race—or circumstances that require additional context. It is the obverse of what so many black historians once derided as widespread historical “whitewashing,” in which only white politicians were praised and black leaders reduced to almost nonexistent bit players. Historical whitewashing entailed writing out certain characters and certain activities that require a fuller context and lengthy explanations, in favor of simpler, more “cohesive”—i.e., one-sided—narratives, It was all driven by a blatant political agenda followed by the onetime majority of white historians.

Much of that whitewashing permitted discussion of only one controversial period figure, Booker T. Washington. His conservative, accommodationist philosophy became a flashpoint in the growing philosophical divide at the turn of the twentieth century between the status quo and so-called “radical” activists, such as W. E. B. Du Bois, the Niagara Movement he led, and the later National Negro Council, which became the NAACP. Even though Washington himself died in 1915, for many decades he remained the rare historical figure who received serious attention by white mainstream historians—and this one-sided approach eventually provoked a course correction, especially after the civil rights era gained momentum.

I get that. I do understand that Booker T. Washington has long become anathema to increasingly agenda-driven black academics, who prefer to ridicule him as an “Uncle Tom” figure—and meanwhile, conveniently ignore the very real contribution he made to his race, both publicly in his Tuskegee Institute operations and his very vocal opposition to lynching, and more surreptitiously, in his quiet funding of early civil rights litigation. He was a complicated, powerful man—no surprise there—but explaining his duality has become tiresome and passe. In a world reduced to only black and white—radical activism good, and white supremacy bad—there is often just no room for nuance. Explaining the context can so easily get in the way of the greater mission …

But back to Ida Wells. My 2008 book, Broken Brotherhood: The Rise and Fall of the National Afro-American Council, explored the 10-year existence of the NAAC, a fractious group split between opposing factions, and which eventually collapsed for lack of funding and capable, farsighted leadership. Yet between 1898 and 1908, the cream of the nation’s black leadership—men and women alike, for the first time—actually grappled with the real and painful issues that still plague the nation a century later: lynching, disproportionate black imprisonment rates, disfranchisement, racial segregation, and the like. And Wells—the strident black journalist from Chicago—was very much in the room, first as national secretary and then as chairman of the antilynching bureau.

The NAAC leadership, Saint Paul, Minnesota, 1902. Courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society.

Study the photograph above of the national leaders of the NAAC at their annual meeting in 1902. In it, Ida Wells stands to the left of Bishop Alexander Walters, the outgoing president. To the right of Walters is Booker T. Washington, whom many NAAC members had once favored to succeed Walters. Just behind Walters and Washington is Washington’s protege, journalist T. Thomas Fortune, who actually did succeed Walters at this meeting. Ida Wells-Barnett had worked shoulder to shoulder with Walters and all the leadership for nearly four years, first as national secretary, then as chairman of the NAAC antiynching bureau.

But the documentary did not choose to mention her contribution—perhaps in part because it would have required some time to explain what the NAAC was, why it was important, or who else was involved. It did not mention that the NAAC held its annual meeting in Chicago in 1899, her hometown. It does not mention her public quarrels with other black leaders who seemed to be enjoying the limelight too much—and advancing the race’s needs too little. Her feuds with Du Bois and others, her sometimes abrasive personality, and her often- shrill writings did not always endear her to all of her racial colleagues, a fate for many larger-than-life figures with powerful opinions—often leaving them alone on the sidelines.

The National Negro Council—eventually renamed the NAACP—grew out of the ruins of the dissolved NAAC. It gave Wells yet another chance to play a leading role in civil rights on a national scale in 1909 and 1910. Yes, the Ida B. Wells documentary does take care to mention the NAACP prominently—even though Wells herself played only a minor role in formation of the new council, and later dropped out completely.

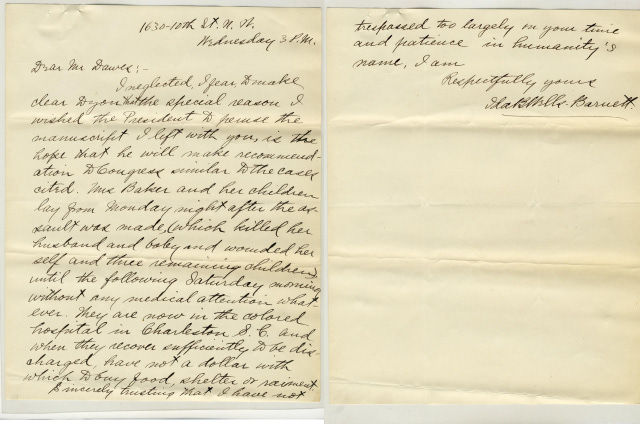

The documentary declines to refer to much of her political activity with white leaders—with one exception, Jessie Lawson, the notable, wealthy and somewhat eccentric wife of a prominent Chicago newspaper publisher. The documentary does cover Wells-Barnett’s suffragist activity, including a 1913 trip to march in Washington’s major national parade. But it does not cover her much longer, and crucial visit—five weeks, in fact—in March 1898 to Washington, D.C., months before the NAAC was formed, to meet with no less than President William McKinley—on the recent murder of black South Carolina postmaster Frazier Baker—and to lock horns on the same subject with the nation’s only sitting black congressman, Rep. George H. White.

South Carolina postmaster Frazier Baker, murdered in 1898 (top),

and his surviving family (below). J. E. Purdy & Co., Library of Congress.

I explored the open-secret feud between Wells and White in my more recent book, Forgotten Legacy: William McKinley, George Henry White, and the Struggle for Black Equality (2020), including Wells’ highly publicized visit to the White House in search of a compromise on public remuneration to Baker’s widow in the spring of 1898. She apparently had the entire Illinois congressional delegation on her side, but failed to persuade White to drop his bill in favor of a similar Illinois measure—which might well have passed.

Ida Wells-Barnett’s letter to Charles G. Dawes, 1898. Courtesy Library of Congress

Wells lobbied skillfully, despite having her nursing infant along for the visit. She soon wrote, for instance, to Charles G. Dawes—a high public official serving as a McKinley appointee, later to become U.S. Vice President—as part of her campaign. As I wrote in Forgotten Legacy, “Accompanied to the White House on March 21 [a month after Baker’s death] by Illinois junior senator William Mason—and seven Chicago-area congressmen, plus many local residents—Wells-Barnett presented McKinley with a four-page typewritten plea, seeking monetary compensation and a federal lynching ban.”

More than 30 years later, long after McKinley’s death, she recalled the meeting in her posthumously-published memoir as a memorable display of the Chief Executive’s gracious attitude: he “received us very courteously, listened to my plea, accepted the resolutions… and told me to report back home that they had already placed some of the finest of their secret service agents” at the scene in South Carolina. In other words, she gave it her best shot.

But White, unfortunately, would not waver. He stubbornly insisted on retaining his bill, ended in its ultimate failure, just as the Spanish-American War loomed on the horizon, and Mrs. Baker never received a dime of federal money. Another tragedy, one that might have been avoided—with a bit of neutral arbitration. Looking back, I think both Wells and White were at fault for the deadlock; I can speculate that a colossal personality clash between the equally stubborn figures only contributed to the situation.

She mentions their face-off in her own posthumously-published autobiography, on which the documentary is largely based, and it it, dismisses White as someone who “did not know the South as well as I had hoped for”—as well as she did, she all but declares. Else he would withdrawn it and have let her have her way. (Almost as if she were the member of Congress, not him.) Strong words, even for an outspoken journalist who did not suffer fools gladly.

White, certainly no fool, may well have bristled at what he saw as a presumptuous demand on her part. He believed, however naively, that the nation’s only black congressman should have his name on the bill. So there was just no middle ground for either of them—no off-ramp for the deadlock which prevailed. A dramatic moment. A truly dramatic moment, but one the documentary simply avoided—and for what justification?

Failing to mention the NAAC, or George White, or even Booker T. Washington—with whom she also openly feuded—or even Wells’ unprecedented meeting with a sitting President: none of this damages the impact of the content of the rest of the documentary, which is otherwise adroitly handled and informative. I learned a lot about Ida Wells I did not know before I watched it. But from another perspective—that of completeness, precision, and balance—it clearly veers away from presenting the whole story of a complicated, talented, and complex woman, flaws and all. The very human being, as proud and stubborn as the very men she was forced to deal with—who could make mistakes but move on.

Granted, the film-makers apparently wanted to concentrate on Chicago and its role in Wells’s life —but it is more than a little shortsighted, in my opinion, to pave over useful details which could only have enriched and added insight. Paving over it borders on historical sloppiness. None of these potholes—however long it might have taken to flesh them out—could possibly have slowed down the flow or interfered with the narrative, which dealt largely with her complicated relationship with the rest of Chicago’s black community. They could only have helped build a complete portrait.

I know the drill. In my 25 years of rescuing George White from the shadows of “whitewashed” history, I have written four books and many articles. It has been a constant struggle; stirring up interest in a long-forgotten black Republican congressman has not been easy. Along the way, I have encountered a lot of apathy, much ignorance, and occasional resistance. A complicated man, with many good qualities—and some outsized flaws—White rubbed many people in both races the wrong way. (Even the new Smithsonian African American Museum passed on including an original exhibit with details on White and most of the 21 other nineteenth-century black congressmen—all Republicans, thus inherently suspect, I guess, in today’s far more polarized political arena. I hope they have since corrected that omission.)

As part of the journey, I have also written the script for one short documentary, and participated in another longer one, on George White’s life and legacy. So, yes, I know you cannot squeeze it all into 15 minutes, or half an hour, or even an hour, without leaving some details out. But I draw the line at leaving out important details which do help, and do not hurt, simply because additional context is required. Especially if they do not easily fit in with the narrative’s very specific agenda of explaining Ida Wells’s significance to later generations.

The dramatic WTTW documentary opens, ironically enough, with a re-created vignette of Wells distributing pamphlets at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Infuriated that African Americans were so poorly represented at the Columbian Exposition, she had helped write that pamphlet—along with venerable abolitionist Frederick Douglass; her future husband, attorney Ferdinand Barnett; and well-known journalist and minister I. Garland Penn—which was titled, “The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition.”

As the documentary depicts, Wells stood tirelessly outside the Haitian government building, the only site which seemed to welcome Douglass as a speaker—a former US Minister to Haiti who had recently resigned over policy differences with President Benjamin Harrison—that year, and handed it to passersby. Because she wanted the whole story out there. She never pulled any punches.

So do I. No, I do not argue that documentaries should not have a clear point of view, a theme, a unifying structure—as long as the context is complete and fair, and supported by all the facts—not just those facts which fit their conclusions. Nor do I argue that dramatic re-creations are not useful in careful doses at holding the viewer’s attention—if I do wonder about the degree of dramatic license employed, and the occasional choice of scenes with little inherent drama and more “agenda” than actual enriching facts.

Leaving out William McKinley, Booker T. Washington, George Henry White, and, indeed, the entire National Afro-American Council—while including reenactments of a rather pointless tea party with Jessie Lawson, or even the frequent photos of a page with her writings slowly appearing in handwritten ink—bespeaks a curiously narrow viewing experience, one I find inexplicably dull by comparison. Where is the substance? Where is the real drama?

The competent, dedicated film-makers who crafted Ida B. Wells could easily have done better, with little effort. I am left to wonder what other inconvenient potholes they might have paved over in bringing their carefully edited version of her truly memorable life to the screen.

Next time: Remembering the USS Maine, and a lost baseball team…