Honoring the man time tried to forget

George Henry White's words still ring true a century and more later

Last week was George Henry White Day in the small town of Tarboro, North Carolina. You might have missed the newspaper articles, not widely distributed outside Edgecombe County. And in case you don’t know the name, you are not alone. But even so, you do need to catch up with his legacy—and there are a small group of dedicated followers who are willing to help.

On January 29, elected leaders and local history buffs in the Edgecombe County seat gathered on the steps of the county courthouse to remember the former two-term congressman, whose 1901 speech in the U.S. House of Representatives—his last after four dynamic years in Congress—recounted the many accomplishments of America’s black citizens since emancipation, and prophesied the return of African Americans to the nation’s national elected ranks.

Bernard George, retired city planner, gives voice to George White’s words. Photo courtesy Rocky Mount Telegram

Bernard George, a regional historian and retired city planner, joined Phoenix Historical Society members on the steps to read excerpts from White’s “farewell” speech, delivered in Washington as that city prepared for the second inauguration weeks later of President William McKinley, White’s mentor and ally, in March 1901.

“I want to submit a brief recipe for the solution of the so-called ‘American Negro problem.’ He asks no special favors, but simply demands that he be given the same chance for existence, for earning a livelihood, for raising himself in the scales of manhood and womanhood, that are accorded to kindred nationalities,” White told his fellow members, in Bernard George’s retelling.

Treat him as a man ... open the doors of industry to him ... help him to overcome his weaknesses, punish the crime-committing class by the courts of the land, measure the standard of the race by its best material, cease to mold prejudicial and unjust public sentiment against him, and ... he will learn to support ... and join in with that political party, that institution, whether secular or religious, in every community where he lives, which is destined to do the greatest good for the greatest number. Obliterate race hatred, party prejudice, and help us to achieve nobler ends, greater results and become satisfactory citizens to our brother in white.

A year before giving that speech, the only African American member of Congress had introduced a farsighted bill to make lynching a federal crime punishable by death. It had itself been lynched, so to speak, dying in the Judiciary Committee, blocked by Southern Democrats, a fact White noted elsewhere in his speech. [See “Town of Tarboro honors a man,” rockymounttelegram.com/features/local/town-of-tarboro-honors-a-man-ahead-of-his-time/article_878bf366-dea9-11ef-b263-a3861dcd6aab.html .]

As he closed the speech, George White then drew thunderous applause as he made what seemed an all-but-impossible prediction:

This, Mr. Chairman, is perhaps the Negroes’ temporary farewell to the American Congress; but let me say, Phoenix-like, he will rise up some day and come again. These parting words are on behalf of an outraged, heart-broken, bruised, and bleeding, but God-fearing people, faithful, industrious, loyal people—rising people, full of potential force.

His prediction would, in fact, come to pass, though not in his lifetime. Ten years after White’s death in 1918, Oscar DePriest would become the next African American congressman, elected from Chicago in 1928, and followed over the decades to come by dozens of successors. It would be nearly seventy-five years before another black Congressman next represented a Southern district, however—Andrew Young from Georgia and Barbara Jordan from Texas, both elected in 1972—and almost a century before another black member of Congress, Eva Clayton, represented North Carolina’s Second Congressional District in Washington, from 1993 to 2001.

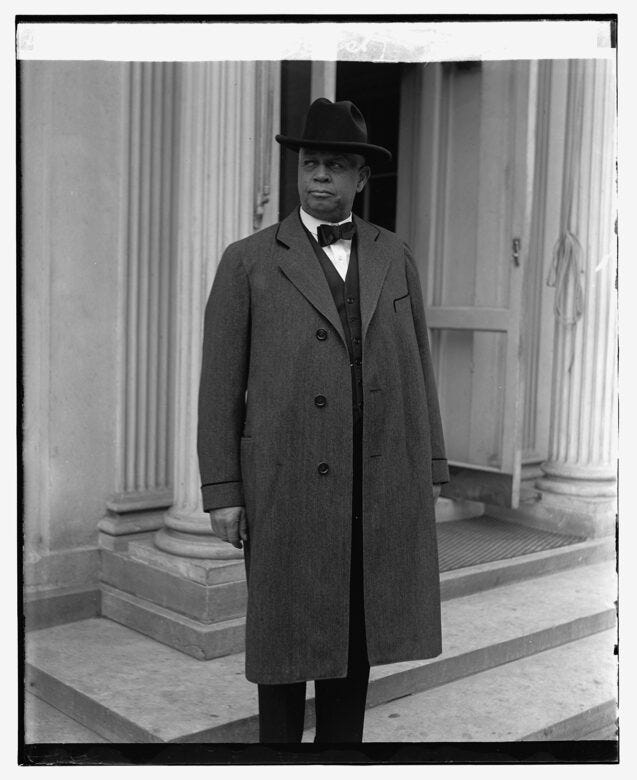

Oscar DePriest (R-IL), George White’s successor in the U.S. House. Courtesy White House Historical Association

Eva Clayton, N.C. member of Congress from 1992 to 2003. Courtesy The Historymakers

* * * * * * * * *

Recitations of portions of George White’s stirring speech have become a regular feature of the celebration of January 29 in Tarboro, the town where White lived while in Congress and the hometown of his third wife, Cora Lena Cherry White.

I must note here that I played a small part in helping restore the former Congressman (1852-1918) to his rightful place in history. I have written four books and numerous academic articles about George White’s life and times since 2000, beginning with George Henry White: An Even Chance in the Race of Life (LSU Press, 2001), which was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in biography. I may have started the ball rolling again, but the lion’s share of credit for his recent rise in historical significance belong to two organizations which took up my cause and ran with it.

George Henry White (1852-1918), pictured just after he left Congress. Public domain photo

The Phoenix Historical Society—an Edgecombe County nonprofit which named itself after that metaphor in White’s speech—invited me to speak in Tarboro after my book appeared in early 2001, and has since distinguished itself by its tireless efforts to revitalize both White’s legacy and the many other important local black leaders who have contributed so much to Tarboro’s growth since the end of the Civil War. George White owes his resurrection there, as it were, to Mavis Stith, Jim Wrenn, the late Helen Quigless, and a host of faithful followers, who petitioned the state to erect a highway historical marker there in 2009 and were instrumental in renaming the local post office after him.

They have since joined forces in promoting George White’s legacy with another nonprofit based in White’s birth county of Bladen, 150 miles southeast. Near the small town of Clarkton stands the flourishing George Henry White Memorial Health & Education Center, housed in a renovated century-old farmhouse with state-of-the-art facilities. That center, which I last visited as a speaker in May 2024, is the brainchild of the Benjamin and Edith Spaulding Descendants Foundation, helping serve the neediest people of both Bladen and Columbus Counties, where White grew up. (His stepmother, Mary Anna Spaulding White, married his father there in 1857.)

Such tireless figures as Vincent Spaulding, Milton Campbell, Stedman Graham, and Kate Tsubata have made the new center a successful and welcome addition to the poor, underserved rural area it now so nobly serves as a sort of unofficial town hall—with grassroots education courses, health outreach, and service projects—by echoing George White’s unwritten creed. One cannot succeed without helping others succeed first—no matter how daunting the obstacles that might block others. Never, never give up. (By all means, check out the center’s website at www.georgehenrywhite.com .)

Months before his 1901 speech, White, a Republican who had held political office in North Carolina since his first election to that state’s General Assembly in 1880—including eight years as the nation’s only elected state solicitor—had chosen not to seek reelection to his House seat in 1900, once state voters amended the state’s constitution to allow a literacy test for state voters. His district, often called the “Black Second,” had elected four black Republicans to Congress for a total of seven terms, on the strength of its majority of black voters, thousands strong in Edgecombe and its sister counties, since 1874. Now the handwriting was on the wall to disenfranchise almost all those voters by implementing a literacy test that would almost certainly discriminate against black voters, while offering illiterate whites a “pass,” in the guise of their ancestral rights to vote: the hateful “grandfather” clause.

The native of Bladen County had begun his career as a teacher, principal, and lawyer in New Bern after graduating from Howard University in 1877. During the summer of 1900, he had campaigned energetically against the constitutional amendment—and considered the “victory” by white supremacist Democrats to be based almost entirely on fraudulent miscounting of ballots. He then declined renomination for a third term to allow a former white Republican congressman to run instead—his fellow townsman, Joseph J. Martin, now town postmaster—in hopes that a white nominee might still be able to rally enough party faithful to squeak by.

It did not work; Martin lost by a 10,000-vote margin in a district White had easily carried in a three-way race in 1898. Martin had planned to challenge his defeat, but died suddenly, a month after the 1900 election, before he could challenge the results in a Republican Congress that might well have seated him instead of his Democratic opponent.

From 1868 to 1900, North Carolina’s Republican Party was primarily composed of black voters—with some estimates as high as 75 percent of its total membership. Nowhere was the party’s black majority more evident than in the Second District, a gerrymandered district created in 1873 by Democratic legislators in an effort to minimize the number of Republican congressmen who might be elected in the 1870s. Northeastern counties with black majority populations, including Craven, Edgecombe, Halifax, Northampton, and Warren—eventually adding Bertie and the new county of Vance—had been grouped together by Democratic strategists, along with other counties with one-third or more black populations.

Republicans had easily outnumbered Democrats across the sprawling district for nearly 30 years, electing scores of black local officials and state legislators as long as votes were counted fairly. In the 1900 balloting for the constitutional amendment, the pro-amendment forces rolled up one-sided victory margins more reminiscent of the elections held in Nazi and Stalinist eras to come in Germany and the Soviet Union, respectively, than the United States—approaching 80 percent in counties that had heavily favored the sitting Republican governor just four years earlier. In one key indicator of outright fraud, the amendment had amassed more favorable votes than the total number of registered voters in some counties.

In the dismal aftermath, with the likelihood fading of a successful court challenge to the amendment’s constitutionality, a badly-disappointed George White angrily told the New York Times that he had decided to move away from his beloved home state after leaving Congress. “I cannot live in North Carolina and be a man and be treated as a man,” he said, embittered. Convinced he could no longer earn a living as the prosperous lawyer he had once been, he never returned to Tarboro, and soon sold off all his vast real estate holdings across the eastern half of the state.

* * * * * * *

His story might well have ended then and there, had he been a lesser sort of man. Yet even in his disappointment, George White never forgot his roots, nor the principled teachings of his stepmother to continue in public service—and against the odds, he arguably accomplished more after he left Congress than before.

Once the nation’s best-recognized African American politician, he never held public office again, yet his energy inspired a new era of self-help and advancement. From Washington, where he first practiced law again, he launched a land development company that created the small pioneer town of Whitesboro in New Jersey’s Cape May County—to encourage black Southerners to create a small paradise of homes and entrepreneurship on the forested site of a former slave plantation, which became his most lasting achievement, one that is still flourishing today.

In Philadelphia, where he moved in 1906, he founded that city’s first black-owned savings bank, and became a stalwart supporter of both civic and philanthropic movements to help the increasing number of black citizens who fled the Jim Crow-era South after 1900. He became a well-regarded leader in the early civil rights movement, as a member of both the National Afro-American Council and its better-known successor, the NAACP.

Yet historians paid little heed to either his accomplishments or his predictions. By the time I first heard of him, he was barely a footnote in most history books—even in Columbus County, where I worked for a time as a newspaper reporter and never once heard his name mentioned. Only after the North Carolina Museum of History thought to include him in a new exhibit on the state’s nineteenth-century black congressmen in 1975—during a period of renewed interest in the modern civil rights movement—did I first hear his name. I was instantly hooked. He has stayed with me for 50 years.

With the help of a widening circle of friends who see White as a principled visionary, I continue to help him preach the pragmatic social gospel he so well embodied. Like reenactor Bernard George, who has carved out a role as his twenty-first century “channel,” I encourage all who will listen to re-examine George White—and learn from his once-forgotten life.

Next time: More foreign affairs in a crazy, mixed-up world

Thanks for a thoughtful and timely post, Ben!