Foreign Service Life in Washington, DC

Part 2: Running into Chuck Norris, Mickey Rooney, and the President of Egypt

Last time out, I began my chronicle of working life in the State Department’s press office in the late 1980s, after Margaret and I returned from a two-year tour in Copenhagen. It set off a whirlwind of activity, mixing often-frantic workdays with far more enjoyable moments, such as the night I got invited to “have dinner” at the White House.

I wasn’t a guest at the State Dinner for President and Mrs. Mubarak of Egypt, of course, and my job, as usual, was to be on call for any assistance journalists might need. Mary Masserini, my good buddy in the Office of the State Department Chief of Protocol, had asked if I would like to come along that night. Of course, I said! (Who wouldn’t?)

President and Mrs. Mubarak of Egypt with President and Mrs. Reagan at White House, January 29, 1988.

Photo/YouTube video courtesy Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

My dinner was included, and even though it was in the White House mess kitchen with other staff working the “show,” it was still delicious and thrilling—imagine a country boy from the South getting to rub elbows—nearly—with such Hollywood elite as Mickey Rooney and Clare Trevor (my parents’ generation) and Chuck Norris (nearer my age). There was precious little for me to do, actually, except gawk. Mary ran a tight ship for her visiting foreign journalists, and it was my first rodeo—but certainly not hers.

Mary was simply a unique person—fluent in at least three other languages, she spent 58 years in government service, and no one who ever met her could quite forget this diminutive child of Italian immigrants who barked orders—and brooked no nonsense—but instantly endeared herself to world dignitaries and workers alike. Handling those often-unruly journalists was like “herding cats,” she once told American journalist Mark Weinberg, but her instinctive grasp of language, protocol, and human interaction made her a favorite with President Reagan, who winked at her every time she entered the Oval Office. Secretary Shultz lovingly called her “the general”—high tribute, indeed. She retired, finally, in 2006, and passed away in 2020, but will never really leave us …

Mary Masserini (1926-2020), spent decades all but running the State Department Office of Protocol.

Family photo courtesy DignityMemorial.com.

Actor Chuck Norris shares a laugh with Secretary of State George Shultz, 1988. Courtesy Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

Actor Mickey Rooney greets old Hollywood friends in New York, 1981. Courtesy Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

Among the 120 or so guests that night were actors and artists (Roy Lichtenstein), politicians and educators, administration officials (my boss, George Shultz, and Mary’s boss, Selwa “Lucky” Roosevelt, from State), a sprinkling of private citizens, and more, all entertained in the East Room by singer Patti Austin. I recognized Mickey Rooney—one of my parents’ favorite child actors, and once briefly married to another country girl who grew up 20 miles from me, Ava Gardner—and martial arts movie star Chuck Norris. (I did not get to meet them, alas, but came really close!)

I also had the near-miss opportunity to shake the President’s hand. The visiting press and selected others were allowed in a short meet-and-greet cocktail hour before dinner, and as the journalists were being ushered out, we staffers were told we could remain for a few minutes with the President, if we wanted to be introduced informally. I was dumbstruck—what would I actually say to the leader of the Free World?—and could I think of a question that did not sound dumb but was appropriate? For once, my natural wallflower’s nature got the best of me—not since junior high school had I ever found myself at a public loss for words—and by the time I mustered up my courage, the moment was gone. Stupid, stupid, stupid …

It was something I still kick myself for, although I made up for it 16 years later, long after President Reagan retired from public office, by standing in line to view his coffin at the Capitol Rotunda, to say farewell to the man who signed my Foreign Service Commission in 1983, “my” first Commander in Chief—even if I did not always agree with him.

I suppose at heart, I have always been a bit of a presidential “junkie,” awestruck by the history—as a kid, I memorized all their names, their terms in office, their wives and vice presidents. A true history buff. I have managed to shake hands with two other Presidents—Bush 41, in Jamaica, when he was Vice President, and later, Barack Obama, in the White House, just before his second term ended—and met the widow and daughter of a third, Lady Bird Johnson and daughter Luci, in Copenhagen; Lyndon Johnson’s campaign event in 1964 was the first time I saw a President in person. (Margaret, however, has actually met former President Nixon at her hotel in 1990, and sat behind former President Clinton as a private citizen at a public function in 2002, lucky girl!)

During graduate school, I even chauffeured the daughter of the late President Harry Truman, who was in the White House when I was born. Margaret Truman Daniel, a now-famous writer of mysteries and biographies, was utterly charming. But that’s another story for another day …

* * * * * * * * *

Being in the State Department press office in 1987 and 1988 inevitably drew the staff into limited contacts with the regular visits to Washington by Soviet leaders, including First Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev and his Foreign Minister, Edvard Shevardnadze, and on occasion, their equally unforgettable wives. We low-ranking officers did not get to meet them, but saw a lot of them from a distance, and felt as if we knew them. Familiarity often breeds more familiarity, not always contempt…

Secretary Shultz and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, with interpreters, during one of many US-Soviet meetings,

Moscow, 1988. Author’s collection

Secretary Shultz , with interpreter, and Soviet Foreign Minister Edvard Shevardnadze, during one of their many meetings,

Moscow, 1988. Author’s collection

Overshadowed only slightly by their respective husbands, Raisa Gorbachev and Nanuli Shevardnadze thrived, nevertheless, as unusually accomplished modern and Soviet women in their own right. Both visited Washington with their spouses, the glamorous professor, Dr. Gorbachev, often upstaging hers—especially during a notorious visit to the White House in 1987, when she created quite a stir—and reportedly nettled Nancy Reagan—by characterizing the White House as a “nice museum” rather than a suitable home for the President. Mrs. Shevardnadze, a well-known Georgian journalist and activist, was far less outspoken but equally memorable. Both fascinated U.S. readers and viewers, as well as press officers, for their out-of-the-box careers and distinctive styles.

Both shed the often dowdy image of most previous Soviet leaders’ wives, combining motherhood and career in publicly unorthodox marriages to adoring husbands.

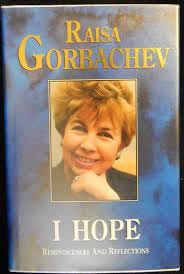

The last Soviet First Lady, Raisa Gorbachev’s 1991 memoir, aptly titled I Hope, quickly became an

international sensation. Photo courtesy HarperCollins.

Despite her own busy career, journalist Nanuli Shevardnadze often accompanied her globetrotting husband

on his world tours. Photo courtesy BBC

Raisa Gorbachev, of course, became the last First Lady of the Soviet Union during her husband’s brief, later presidency, while Nanuli Shevardnadze was destined to become First Lady of independent Georgia after the collapse of the USSR. Few Americans were doubtless yet prepared to think of our First Ladies as independent, working women—with the most notable exception of Eleanor Roosevelt, who forged a remarkable career as a journalist, author, and diplomat after leaving the White House—although many other U.S. presidents’ wives had worked prior to marriage, including Mrs. Reagan, a onetime Hollywood actress; and Jacqueline Bouvier, a professional photographer when she married John F. Kennedy.

I had, of course, recently met Lady Bird Johnson, a trained journalist and savvy businesswoman who owned and managed Austin, Texas, radio stations and a TV station during her marriage, and after Lyndon Johnson’s death, amassed a profitable media company. But except for Mrs. Roosevelt, most U.S. first ladies concentrated during their White House years on their public images as family nurturers and supportive campaigners, not active career women. Observing the Soviet spouses was giving me valuable new insights into American life—both in U.S. work habits and the increasing presence of female Foreign Service Officers. At least half of the members of my intake class in A-100 (initial training) had been women—reflecting, perhaps, the increased presence of women students in college ranks.

When I started classes as a freshman at UNC-Chapel Hill, the campus was 90 percent male. That was in 1967. By the time I returned to graduate school there in 1981, the campus had been transformed into a female majority … it was definitely a new world.

* * * * * *

Before leaving Copenhagen, I had begun dreaming of a possible transfer to the still-independent U.S. Information Agency—where one of my childhood journalistic idols, Edward R. Murrow, had once worked—and my adventures at the press office quickly deepened my interest in returning to a job more relevant to my original journalistic roots. After being briefly seconded to help out the press office at the U.S. mission to the United Nations in New York, I was almost positive it was what I truly wanted to do.

Then life got in the way. Up for promotion to FS Level 3 in the early fall of 1987, I was mildly disappointed by not achieving it my first time out—and thus far less like likely to pull off a successful transfer—but guessed (hoped) that a year in the press office might burnish my credentials, and the second year of eligibility was usually more favorable. So I enlisted the assistance of a friendly USIA colleague—the public affairs officer in Copenhagen, Mary Ellen Connell, who graciously sounded out her headquarters for possible vacancies at my level. Most of them, however, were language-designated, and the only open English-language slot was a branch public affairs officer at a one-officer operation at the U.S. consulate in Lahore, Pakistan.

It was actually not a bad opportunity, although I had some misgivings about living so far from the main Embassy in the smaller capital, Islamabad, which was several hundred miles away. Lahore was a very large city, with all the advantages (and disadvantages) of a South Asian metropolis; it was located in a turbulent part of the world, and halfway around the world, at that. Just getting back and forth to Pakistan was tricky enough, requiring long flights; how often could I even get home if I needed to? Housing was a secondary consideration, followed by security (would I be wearing a target on my back?). As far as medical care went, I was in good health, but I worried about availability of medical care for my working wife, a Type 1 diabetic, who was very active and otherwise healthy. Margaret had received world-class medical care during a complicated insulin transition in Copenhagen, and very good care so far in Washington.

Despite its size and cosmopolitan reputation, I was not so sure about what to expect in Lahore—or if she would even be medically cleared to travel there—and even less convinced I wanted to live there alone. (State Department regulations permitted families to remain behind in the U.S. on separate maintenance allowances, under certain conditions.)

Still, I pondered what to do next. To get promoted to the level of FS-3, I was now being told, discreetly, that I probably needed to consider taking another administrative posting after Washington—that even a very strong evaluation after my press office posting might not help much, if at all—and that was certainly not my first choice. I had wanted to join USIA at the very beginning, in 1983, but a hiring freeze that year made it impossible. Turning down even a less-desirable transfer to USIA now might ruin any chances I had later on, if/when I delayed and tried again. I was still mulling the possibility when our U.S. ambassador to Pakistan, Arnie Raphel, was killed in August 1988 in the mysterious crash of a plane carrying the Pakistani president, Zia-ul-Haq. Probably sabotage, we were told, and aimed at Zia; poor Arnie was collateral damage.

I did not know him personally. But I grieved for him, and his widow, also an FSO. His sad end recalled the kidnapping-murder next door of our ambassador to Afghanistan, Adolph Dubs, in Kabul nearly a decade earlier, and emphasized the perils of living in an unstable political environment. As a single officer, I might have shrugged it off; as a married man, I had more than my own skin to worry about. Just after the ambassador’s death, I had to start compiling a list of possible postings to bid on for fall of 1989.

I did not really want to go to Pakistan now. Maybe a transfer to USIA might still be possible in 1991? So it was with a heavy heart that I began looking for administrative jobs again—concentrating on relatively safe cities with good medical care, but weighing the advantages of certain hardship bids (more money and shorter time spans)—and hoping against hope that at least I did not have to consider more language training any time soon. I had begun to realize how complicated, in fact, planning was for the typical 20-to-25 year career of an FSO. (We were allowed to retire, by law, after 20 years, at age 50; I would be eligible at 53, when my 20 years were up, or could continue until mandatory retirement at 65.)

All this meant a maximum of nine or 10 2-year (hardship) posts, with required training thrown in, or fewer if one took (non-hardship) 3-year postings, which were becoming more and more common. After five years, I was in my third job at State—meaning I had only six or seven postings left before “early” retirement, perhaps nine or 10 if I stayed in until my 60s, including at least one or two more jobs in Washington. So every bid list became more and more important in terms of long-range planning, all requiring careful. consideration.

No more “this sounds good” or “I’ve always wanted to live there,” but more pragmatic: how much help will each of these jobs be to my career plans?

Next time: Part 3: Back on the road again—leaving Washington for the “real” Foreign Circus