Foreign Service Life in Washington, DC

Part 1: Joining the press office and 'starting over' at home

Coming home after two tours abroad, even with intervening language training thrown in, generally requires a new mind-set for Foreign Service officers. Even if done by choice—as mine was—coming home to work in the Department of State can at best be a jarring transition, especially if it requires finding permanent housing and a new car. That’s when the legally-mandated “home leave”—30 days of paid leave after two or more years abroad—comes in handy, giving you time to get reacclimated and build a new household from scratch, while waiting for household effects to be shipped home.

I hated to give up my little Volvo sedan—not manufactured to U.S. specifications, and therefore not eligible to be shipped home—but sold it to my successor in Copenhagen; Chris and his family needed an immediate car, and the price was right. Then Margaret and I spent my leave visiting my family before shopping for a house and replacement car. We lived temporarily with generous friends; by the time I had started working at the press office, we had found a convenient townhouse we could afford in the Alexandria section of Virginia’s Fairfax County (just off the Metro Yellow Line) and a very used Volvo (what seemed like a bargain became an expensive mistake). All just in time for Margaret to start her own (unexpected) new job as an assistant concierge at a small hotel on Massachusetts Avenue.

We both instantly loved our new jobs—I felt as if I had finally found something that challenged me in the right way, working under a USIA officer seconded to run the press office, alongside one other FSO and mostly career civil servants who knew their jobs inside out. Margaret stumbled into her job by visiting the hotel, where a good friend worked, and being interviewed on the spot for a vacancy—it suited her perfectly. Meanwhile, Cognac quickly adjusted to life as an American dog with two working parents—even during the freak, early Veterans Day blizzards that dumped two feet of snow on us, shades of the Danish winter we thought we had left behind!

Dennis Harter was a great boss, and the crew of civil servants he oversaw turned out to be a terrific, welcoming bunch. The press office was an extremely busy place—we spent our mornings preparing the Department’s spokesman, Chuck Redman, for his daily noon briefings of the press, mainly by harassing other bureaus for the approved language on expected topics of the day on a very tight daily deadline. Diplo-speak, as I thought of it, was an art: how to stretch the truth to fit the political aims of the administration without actually lying (too much, anyway). Experienced journalists parsed every single word of the daily briefing carefully to see what, if anything, had changed since the last time a question was asked and answered—and to speculate on what the administration was NOT saying and what it all meant.

Chuck and his assistant, deputy spokesman Phyllis Oakley, were old hands at this. Much like their boss, Secretary George Shultz—a tried-and-true veteran of previous political wars, who knew exactly what to say, and could not be tricked or trapped into venturing beyond his brief—they were experienced, surefooted FSO’s who knew their topics and jobs well. Phyllis had originally been an FSO in the 1950s before marrying another FSO, now-Ambassador Robert Oakley, and being forced to resign (married women, for some reason, were banned from the ranks until 1973); when she was brought back in, she quickly rose through the ranks. Chuck went on to become Ambassador to Sweden and then to Germany before retiring in 1996; Phyllis was an Assistant Secretary before retiring in 1999.

Phyllis Oakley, the Department of State’s deputy spokesman in 1987 (pictured 1999). Photo courtesy New York Times

I admired them both. They were a perfect pair—Chuck the serious and unflappable, cerebral spokesman and Phyllis the livelier, occasionally unpredictable stand-in with a sly sense of humor. Both clearly knew what lines not to cross. Once, unmistakably annoyed at a persistent journalist’s needling of her for the clear-as-mud approved talking points on a hot-button issue, Phyllis fleshed out her frustration with a line not in her briefing book, which brought gales of laughter and practically wrote the next day’s headline: “Well, if it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck, I think you know what it probably is.”

That line, generally first credited to former labor leader Walter Reuther during the McCarthy anti-Communist era of the 1950s, was a familiar common-sense phrase defining “abductive reasoning”—the simplest conclusion one could draw from a set of observations, but one very few diplomats would ever be comfortable using. Phyllis was a well-trained graduate of the Tufts University School of Law and Diplomacy, and gifted with keen analytical skills—but also possessed a no-nonsense sense of the surreal world some of those journalists seemed to live in. I thought what she was actually saying was something like “Look, friend, you can be as stubborn as you like but you are getting nothing more than the briefing points—so quit badgering me. Think. You know what the words mean.”

These daily briefings were often a delicate dance. And journalists who did not accept or understand the essential diplomatic code were at a real disadvantage. The hidden, nuanced meanings within the diplomatic code—always critical distinctions—were sometimes lost on the less expert journalists, who either did not know the evolving history of certain policy issues or did not care to do the research—and wanted something juicy, easier to sensationalize. So it was frustrating for all concerned. We FSO’s—especially those, like me, who had actually been working journalists—often sympathized with reporters but could do little or nothing to illuminate them without violating our own, carefully prescribed roles. Trusting a journalist was not a prudent course of action; accidentally revealing a “secret” without permission was a risk we knew could end our careers. We could not go “off the record,” even with friends.

For centuries, diplomats had carefully refined this code to allow them, in effect, to fib to each other, sometimes outrageously so, on behalf of their governments without actually lying outright—speaking with their fingers crossed, as it were—until the desired international political outcome was achieved: war, peace, economic or political alliance, whatever. Diplomats, at least, understood the historical reasoning behind their own actions and the necessity of a mutually intelligible language of discourse to assist in achieving a goal. Diplomats, after all, were expected to be honorable creatures—not “honest,” necessarily, but honorable.

The far cruder politicians who needed this diplomatic “cover,” however, rarely cared about such niceties. (As creatures of the moment, their sole motivation was self-preservation; politicians could simply lie as desired, until, when politically expedient, a change at odds with everything previously said could be announced, without blinking an eye.)

But there was an occasional tool that Chuck and Phyllis—and even the Secretary himself, on occasion—could use, when needed, to fill in the blanks: the “background briefing,” at which the briefer morphed into the role of unnamed “high-level State Department official” to explain the details of a certain issue or action. It was a kind of sanctioned “safety valve,” reserved for very new or complex issues that few outside the Department understood very well. It provided a brief, choreographed peek behind the curtain at the inner workings of diplomacy.

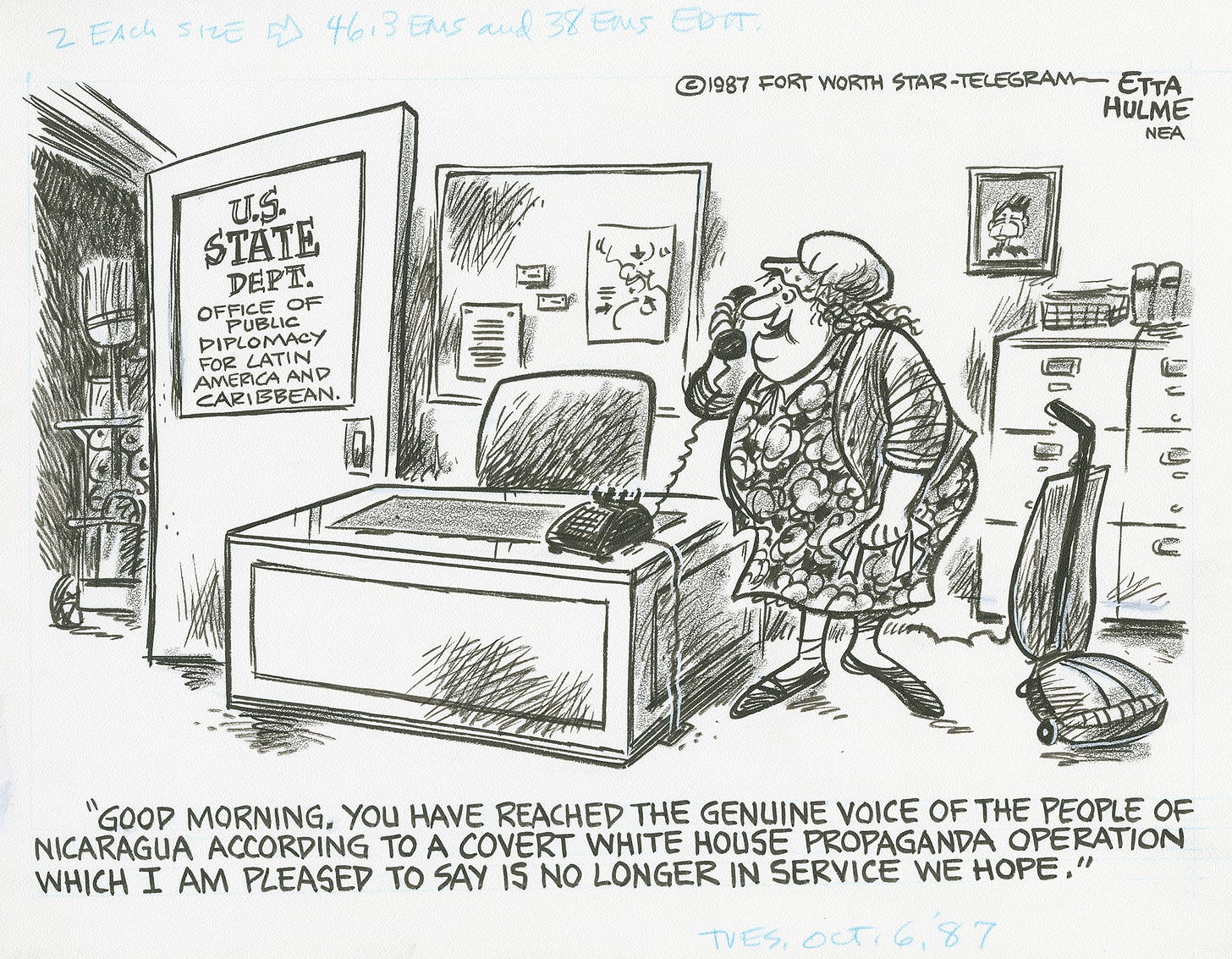

My tenure at the press office, of course, coincided with the waning years of the Reagan administration, already infamously tainted by the lingering after-effects of the “Iran-Contra” scandal—and journalists were often loath to accept any explanation that seemed self-serving or too conveniently timed.

Cartoon printed October 1987. Courtesy, Etta Hulme Papers, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries, Special Collections

So “background briefings” were often intended to build credibility—by being focused mainly at the acknowledged opinion leaders in the media world, the larger newspapers and networks, as much as at the individual State Department correspondents themselves. Here’s the rest of the story, these briefings promised.

On rare occasions, when a critical issue required his presence, Secretary of State George Shultz would hold the daily briefing, using the same briefing book as his spokesmen would have used that day—but free to depart from the language it contained, of course, if and when he saw fit. His appearance was usually called for only when an extremely important high-level announcement was planned, and was often far shorter than the normal briefings. He rarely took questions at the end, and when he had said his piece, left the briefing room abruptly, accompanied by his detail of Diplomatic Security guards.

One of my jobs, shared rotationally with other press officers, was to open the closed door to the side hallway at the close of each briefing. It opened inwardly, and the officer nearest the door usually stood up when signaled from the podium by the spokesman, made sure the door was secured in an open position—into a small area next to chairs reserved for us only—and then stepped aside. One extra chair blocking the usual standing space at a crowded briefing given by the Secretary, making it impossible for me to step aside fast enough, however; despite his size, he moved very quickly, so I wound up face to face with him, almost tripping him on his way out.

One of his DS guys unceremoniously pinned me up against the wall—firmly, if gently—and barked, “Stay,” as the small entourage exited the room. I did as ordered.

George Shultz walks with President Ronald Reagan outside the Oval Office in December 1986. Courtesy, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, National Archives and Research Administration

The Secretary was only an inch shorter than me, older, stockier, and bless his heart, held no grudges. He was my father’s age, almost exactly, and like him, a World War II veteran. He was a solidly built Marine, after all, and used to combat. But he had a good memory. The next time he saw me—in a receiving line shaking the hands of staff departing his aircraft during a trip to the UN in New York City—he gave me a wide berth, acknowledging our previous encounter. . He shook my hand from a careful distance, eyeing me carefully all the while. I remember you, his eyes said, and am taking no chances today.

* * * * * *

Our afternoons in the press office were devoted to catch-up work—running down the “taken questions” not covered in the briefing book and proofreading the written transcript of the briefing, which was published and posted every afternoon. To get it right, one officer had to listen to the entire taped briefing while reading the transcript typed up by one of the Department’s experienced transcribers.

It had to be letter-perfect, meaning every name mentioned was spelled correctly and there were no factual errors in the as-heard reproduction—sometimes that meant contacting the spokesman as a last resort. Time-consuming, depending upon the length and breadth of the briefing, it was not a task any one of us looked forward to, so it was also rotated. Nancy Beck, Gladys Boggs, Rudi Boone, Sondra McCarty, Anita Stockman, and I shared the honors.

Occasionally, journalists who had not attended that day’s actual briefing would call in and ask for a portion of the transcript—or less often, a posted release with language prepared for but not actually used in the briefing, or the answer to a taken question—to be read aloud to them by telephone. Whoever answered the call became the “spokesman” for that moment, meaning my name was occasionally attached to articles printed in national publications—and sometimes, more rarely, our actual voice-overs would be broadcast on radio.

One of my coworkers, on leave one particular week, told me when he returned that he had heard me on the radio while lying on the beach in Antigua … and for one brief, horrible moment, thought he was back at work, not on vacation at all. I went on vacation to get away from you, Rudi Boone told me on his return, and you came anyway …

And while most of our work was deadline-driven and highly stressful, some of it could occasionally also be pure fun. In previous postings, I have already recounted my trip with the Secretary’s party to Finland and the former Soviet Union—Moscow, Kyiv, and Tbilisi—in April 1988, when I was the “shepherd” for traveling press. On another trip, I spent several days seconded to the press office US Mission to the UN in New York, perhaps as an encouragement to bid on that as a future post.

And one added perk was getting to know a lot of people throughout the ranks of the State Department—either by daily dealings with them over approved briefing language, or by chance encounters leading to future meetings. On one such adventure, I got a guide tour of the Blair House guest complex for dignitaries, just across Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House. On another, Margaret and I spent a pleasant afternoon at Phyllis’s house for a cocktail party honoring Marlin Fitzwater, the White House spokesman.

On a third occasion, I ended up spending a star-studded evening at the White House, which was a rare honor.

Next time: Running into Chuck Norris, Mickey Rooney, and the President of Egypt ….