Foreign Service Life in Asia: Quirky, rich, distinctively dull Brunei

Part 1: Getting to Bandar is easier then expected, but still risky

The Foreign Service can lead you to some quirky destinations. Brunei Darussalam is a bit of a puzzle, geographically and historically. It is mostly the personal domain of one of the world’s last two ruling sultans, until recently the richest man on earth—a tiny Delaware-sized country in two noncontiguous portions, atop a Texas-sized island largely controlled by two other countries, Malaysia and Indonesia.

Its ruler, Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah ibni Omar Ali Saifuddien III, is one of the world’s last absolute monarchs, now in his late 70s. (There are still many ceremonial sultans around, but only one other sultan still rules a country, Oman.) When his sultanate gained final independence from a century of British rule in 1984, Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah became prime minister, as well as owner of the fabulous oil wealth of Brunei, giving him an outsized role in world affairs. Oil explorations began in 1929, and currently provide more than 90 percent of Brunei’s exports.

You can see more about Brunei’s government and history in the BBC’s compact but detailed country report [ at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-12990058 ].

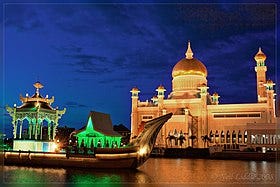

Bandar Seri Begawan and its main mosque by night. Public domain photo

Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah ibni Omar Ali Saifuddien III. Public domain photo

The country itself is distinctive, almost bizarrely so—its fewer than half a million residents enjoy one of the world’s highest standards of living, thanks to the generosity of its aging Sultan—but it is far from a paradise. In 2014, it became one of the few countries outside the Middle East to impose sharia-style law on its mostly Muslim citizens. So its citizens can technically be stoned to death for adultery or committing homosexual acts—although Brunei has agreed, at least temporarily, not to enforce that specific penalty—and anyone can be executed for trafficking illegal drugs, with no appeal.

According to the U.S. State Department’s Country Security Report for 2023, ”Penalties for possession, use, or trafficking of illegal drugs are severe. Convicted offenders can expect long jail sentences, heavy fines, corporal punishment, or, in the most severe cases, the death penalty. Though Bruneian law provides for death sentences for many narcotics offenses, the sultan of Brunei has declared a moratorium on capital punishment.” In addition, as the Report notes, “Firearms, alcohol, prostitution, drugs, and gambling are illegal in Brunei,” with most foreigners likely to be fined, imprisoned, or deported for violations.

So if you should wish to visit Brunei, be forewarned. Misbehavior is not welcome.

Its lingering appeal to tourists relies mostly on travelers’ fascination with such peculiarities as the Kampong Ayer—the traditional water villages, sometimes called “Venice of the East,” where more than 10,000 people live in an area of nearly four square miles above the waters of the Brunei River. It is the largest of a dwindling string of such villages, and contains schools, mosques, businesses, and wooden walkways built over a mystifying hodge-podge of stilts.

Kampong Ayer, the unique water village municipality, near the city center of Bandar Seri Begawan. Photo courtesy Balou46.

Most visitors also come to gawk at the Sultan’s mammoth, opulent palace, which cost more than $1 billion to build in 1983, using Italian marble, granite from Shanghai, English glass, and the best Chinese silk. Gold and 38 different kinds of marble were the main decoration materials of the Palace’s nearly 1,800 rooms, 44 staircases, five swimming pools, and more than 250 bathrooms. The world’s largest residence for a head of state, with more than 200,000 square meters of floor space, Istana Nurul Iman also houses a handful of government offices. [Think the White House, at a paltry 5,000 square meters, gone wild …]

Istana Nurul Iman, residence of the Sultan of Brunei. Photo courtesy http://www.istananuruliman.org

On the throne since his father’s abdication in 1967, the Sultan is now the world’s longest-serving monarch, following the recent death of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II. Married since 1965 to Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Hajjah Saleha (the Queen), by whom he has six children, he also has six other children by two now-ex-wives. It is not clear whether all those 12 princes and princesses continue to live in the Istana Nurul Iman (though there is certainly room for them). The family also owns a reported 150 other homes in a dozen other countries, as well as a small personal air force—more than a dozen airplanes—to transport them wherever they need to go.

The reports of their outlandishly extravagant lifestyles are plentiful—but only outside the country; inside Brunei, discussing the royal family in print is severely discouraged.

* * * * * * *

I had occasion to visit Bandar several times in 1991, though hardly as a tourist. During that year, I was posted as a Foreign Service Officer to Singapore, as the U.S. Department of State’s regional personnel officer for our embassies in Bandar, Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia), and Singapore. Back then, our Bandar embassy was housed in a small, low-key suite of offices in a nondescript commercial building, although the U.S. government has since upgraded its presence to a distinctive new compound—near the embassies of India and the Philippines—after Brunei signed a military memorandum of understanding with the U.S. Defense Department in 1994. (I never had occasion in 1991 to meet the then-Ambassador, a political appointee who seemed to travel frequently and departed post permanently in the fall.)

My visits there were generally to assist the Embassy’s administrative section chief, Omar Bsaies, in processing paperwork for a small staff of Foreign Service National employees. During at one of my visits, I stayed with Omar and his wife in their very comfortable, very roomy residence, rather than in the fairly spartan hotel generally used by visitors. Omar was a liberal Muslim, originally from Tunisia, as I recall, and he and June were gracious hosts, inviting me and Margaret to stay with them and their two kids on her only visit there, coincidentally during Ramadan.

And if I fleetingly considered the possibility of bidding on Omar’s job when his tour ended—largely for the marvelous housing—I soon reconsidered, as other more inviting opportunities outside Asia supplanted Brunei on the list. Living there requires a kind of inner self-reliance that soon grows tiresome, and “island fever” quickly sets in. The emptiness of social life, the stultifying atmosphere, and unlikeliness of visitors would have been anathema to Margaret, a committed globetrotter and shopper who fell in love with Singapore as a combination home and travel hub.

Visitors outside U.S. embassy in Bandar, 2023. Photo courtesy https://bn.usembassy.gov/diplomats-for-a-day.

Getting to Brunei from Singapore, at least, was easy—several flights a day aboard Singapore Airlines or Royal Brunei Airlines—and quick, about 2 hours to cover 800 miles. Probably the only disadvantage, frankly, was the culture shock: modern Singapore was definitely more sophisticated and cosmopolitan, bustling with energy, commerce, and thousands of tourists, while Brunei seemed far more like the backwater afterthought it truly is—a mildly glitzed-up version of the 16th-century sultanate that once ruled all of Borneo. Densely-populated, high-rise Singapore, at that point, had more than 3 million residents (now more than 6 million!)—including more than 20,000 Americans when we lived there. Meanwhile, Bandar held fewer than 100,000 people, or about 20 percent of the entire country’s population, and seemed more like an overgrown, sprawling village than a city.

Part of that, of course, was due to the geography of the island of Borneo, whose northern coast includes the tiny country, mostly a narrow coastal plain with hilly lowlands and a few mountains, and literally dwarfed by its other neighbors on the island: the provinces of far more populous Malaysia (4 million citizens on the island) and Indonesia (12 million). According to one description (PBS, “Borneo: Island in the Clouds”), the weather there—not all that different from steamy Singapore—still takes some getting used to: “With a generally hot, wet climate, rain is more common than not, with some portions of Borneo receiving between 150 and 200 inches of rainfall annually. Between October and March, monsoons buffet the island.”

Even in good weather, however, life in Bandar also ran at a much slower pace than elsewhere, due primarily to increasingly restrictive Muslim effects on ordinary life. Most local residents choose to stay home at night. Nowadays, the sidewalks and streets are generally empty after 11 p.m., although some coffee bars catering to a younger crowd may stay open after midnight. Crime is rare, but visitors are still encouraged to be sensible and not go out alone at night.

On the whole, Bandar simply had and has little to offer in forms of Western entertainment: no alcohol, no nightclubs, only a small number of movie theaters showing Western movies (I checked, and both “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” were showing this week, presumably edited for objectionable content). Local women must now dress according to Islamic code—hijabs are mandatory—but female visitors are gently encouraged to dress conservatively (arms, shoulders, knees covered) and open sandals are frowned upon. In 1991, at least, tourists of either sex could enter local mosques, but only if dressed properly; men in shorts had to don robes provided at reception and women were offered head scarves. I did not visit any of the Brunei beaches, but suspect that women’s Western-style bathing suits are not welcome there.

The government operates the only television station and one radio station, with broadcasts tightly controlled, although satellite television and cable service are available. A handful of newspapers—including the Borneo Bulletin in English or the Malay Media Permata—and even an online news service, exist, but all must operate under strict guidelines. Above all, no criticism of the government or unfavorable mention of the royal family is ever tolerated.

According to one reasonably neutral assessment (found on www.pressreference.com), “Brunei's press, although not considered free by Western standards, is what the government describes as a ‘socially responsible Press,’ which balances the rights of the individual and those of society.” Newspapers and foreign media remain censored in Brunei, if with a somewhat lighter hand in recent days. But local religious leaders continue to express “their concern over less censorship because they believe the society will fall into moral decay, according to the BBC News.”

Bruneians are generally well-educated, prosperous—most families have two cars—and friendly enough to strangers, if not especially outgoing. Accustomed to the benevolence of the overly-paternalistic sultan, they don’t seem to travel much. So it is no surprise that tourism is not a dynamic industry, or that few expatriates choose to live in Brunei for any length of time—even with its high-quality free medical care, cheap gasoline, and low rates of violent crime. It is just too dull.

Even diplomatic circles in the capital are a pale reflection of those in larger cities. The U.S. Embassy, open since 1984, is one of just 29 smallish embassies or (British Commonwealth) high commissions in Bandar today—including those of Australia, Canada, France, Germany, India, Japan, the Philippines, and the United Kingdom. Most other nations serve Brunei from their regional embassies in larger Asian cities, most from Jakarta or Kuala Lumpur.

Is it worth seeing once? Yes, if just to cross the Kampong Ayer and sultan’s palace off your bucket list. After that, I see little reason to return.

Next time: Part 2: Mysterious Malaysia, mixing Islam and gambling casinos