I wonder what the king is thinking tonight. The king of Denmark, I mean—who has recently redesigned the monarchical coat of arms, his 1,000-year-old family’s ID, so to speak—to reflect his updated view of what it means to be Danish in a turbulent new world, where history is ignored and selfish ignorance seems to be the new mantra.

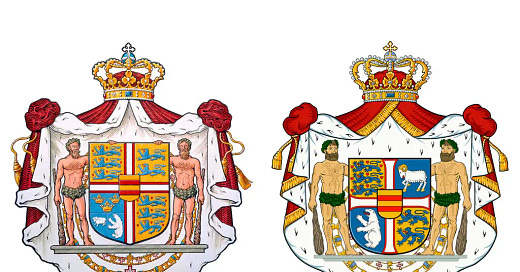

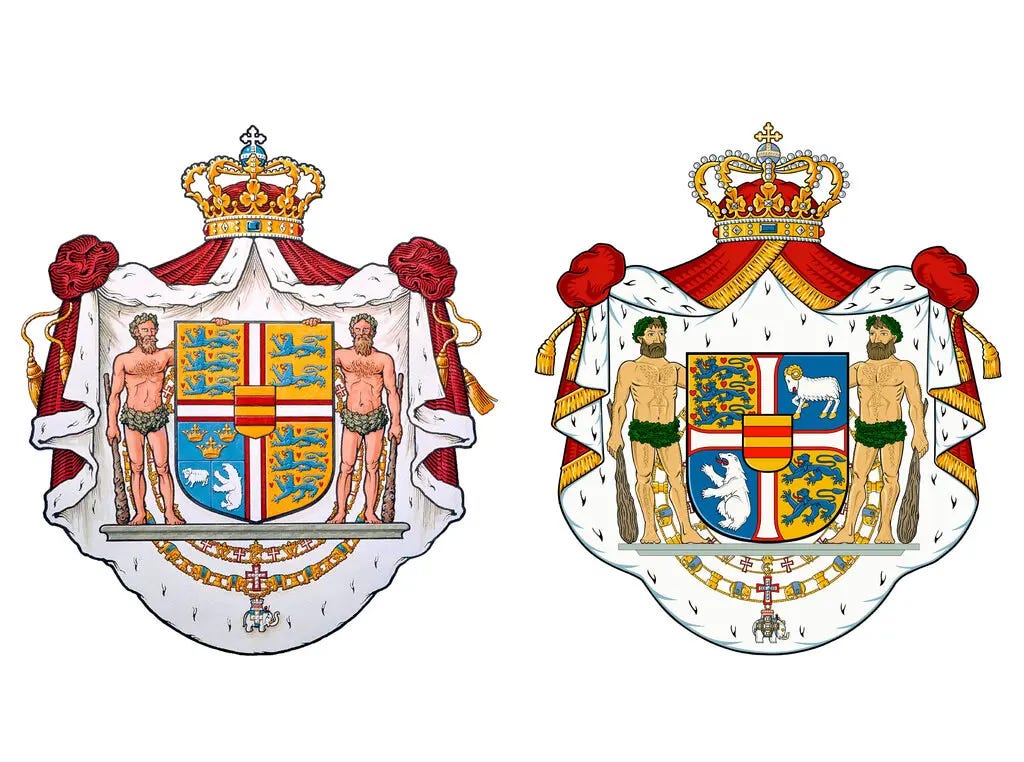

According to the New York Times, Frederik X recently “implemented changes to the Danish royal coat of arms that reaffirm his kingdom’s commitment to Greenland, a sovereign territory. The Danish royal coat of arms — a more elaborate symbol than the kingdom’s national coat of arms — had previously featured a panel with three crowns that represent the [old] Kalmar Union between Denmark, Norway and Sweden … with separate panels [now] being dedicated to Greenland (represented by a polar bear) and the Faroe Islands (represented by a ram) [below, right].”

At right, King Frederik X shows his subtle response to U.S. rudeness in seeking to bully Denmark to sell Greenland. Courtesy New York Times

It was a subtle but unmistakably firm thumb-in-your-eye signal to the incoming U.S. president, who seems obsessed with bullying a small peaceful U.S. ally into selling off excess real estate. Sorry, Donald, the world’s largest island is not for sale … at any price … to you or anyone else. [See “With Trump Coveting Greenland,” January 7, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/07/style/denmark-coat-of-arms-trump-greenland.html]

It’s not as if prosperous Denmark needs the money. Nor does it really want to hang onto Greenland—the huge island it has ruled peacefully for 400 years, since British colonies first began springing up in North America—against the natives’ will, mind you. To its credit, the Danish government has quietly been grooming Greenland for eventual independence since well before Donald Trump’s first bankruptcy—achieving home rule in all but foreign affairs and defense in 2008—and two members of its Folketing (parliament) currently take part in Danish politics.

Greenland has not yet asked for its final freedom from Denmark, probably because it is still to their financial benefit to hew to the status quo. Without an independent military force, Greenlanders are not yet capable of defending themselves against an aggressor without outside assistance.

Frederik X, now the King of Denmark, is well aware of that; as a seasoned military officer, he was briefly assigned as a dogsled team member, the so-called Sirius Patrol, there at the turn of the twenty-first century while still Crown Prince—and carefully keeps the island’s future in mind, witnessed by the enlarged polar bear on his revised coat of arms. He has also served twice as a Danish diplomat, both at the UN and in Paris, before ascending the throne—and understands that bluster from friends and adversaries alike is often best met with the same firm courtesy.

Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark, while a member of the Queen’s Life Guard Regiment in 1986. Photo courtesy CNN

Back to Greenland in 2004 with his wife, Mary, on a sledding trip. Courtesy Washington Post

But if Greenlanders themselves, all 57,000 of them, take that final step toward independence—and then decide they want to consort with Americans on a more permanent basis, like Puerto Rico or Palau, well, it’s their choice. (Warning—despite their small numbers, Greenlanders are a fairly independent sort.)

Situated ‘twixt Canada and Iceland, Greenland is content to be Danish for the moment. Map courtesy BBCnews.com

It seems to me to be a case of astounding historical ignorance—perhaps even illiteracy—among Americans, who should be able to read history, and draw sensible conclusions about future actions based on past outcomes. It is appalling, to me, at least, that no one seems able to dispel the atmosphere of hubris and chest-thumping. Too much testosterone, too little patience—and a distressing lack of both finesse and brainpower.

* * * * * *

It is not that there are no historical antecedents for the subject, of course. Due to their strategic positions, both Greenland and neighboring Iceland were temporarily occupied by U. S. military forces during World War II, to prevent a less-friendly occupation by Nazi Germany during its occupation of Denmark. Germany had already tried to bully neutral, quasi-independent Iceland into allowing a military base even before it occupied Denmark in the spring of 1940—and Hitler had its eye on Danish overseas territories next.

The U.S. military has also operated an air base in northern Greenland since 1951—Thule Air Base, since renamed Pituffik Space Base—under a NATO agreement with Denmark, now one of its closest allies, with a few hundred servicemen still stationed there.

The acquisition of Greenland has been seriously raised several times since 1867, at the same time Alaska was successfully acquired from the Russians just after the Civil War. But like a similar move to annex the Dominican Republic by treaty in 1871, that first project was scuttled by Congress for political reasons. I won’t go into detail here, but readers are well advised, if interested to study a wonderful 1940 article on the subject by Brainerd Dyer [“Robert J. Walker on Acquiring Greenland and Iceland,” available at https://rse.hi.is/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Dyer.WalkerPurchaseofIceland-2.pdf .]

Similar proposals since then—most notably, in 1910 and 1946—have also come to naught, generally because Denmark preferred to keep Greenland, and did not agree to the secret terms advanced by U.S. leaders most recently after World War II.

Proposals to purchase the Danish West Indies—Denmark’s other royal territory in the Western Hemisphere—were also unsuccessful until 1915, when the possibility of German aggression in the Caribbean starting alarming U.S. leaders. Earlier efforts had failed, in part from political issues and in part because the U.S. offer was always too low.

According to the U.S. State Department chronology, in 1915 “U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and Secretary of State Robert Lansing feared that the ]Kaiser’s] German government might annex Denmark, in which case the Germans might also secure the Danish West Indies as a naval or submarine base from where they could launch additional attacks on shipping in the Caribbean and the Atlantic,” including nearby Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory. The yearlong negotiations included veiled threats that if Denmark refused to sell, the U.S. military might act summarily to occupy the islands. [See “Purchase of the U.S. Virgin Islands, 1917,” at https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/wwi/107293.htm .]

The U.S. Congress duly appropriated $25 million, paid in gold bullion—the equivalent of about $616 million today—which was accepted by the Danish government. That was how the U.S. Virgin Islands finally became an unincorporated territory of the United States—just weeks before the United States entered World War I in April 1917. But its acquisition still left a bad taste in the mouths of some Danes, who resented the heavy-handed nature of the whole affair, even in wartime.

And the new U.S. administration’s interest in Greenland is continuing to rankle Danish leaders, including a Danish member of the EU Parliament, whose profanity in a speech this week before Parliament drew a reprimand and fine for unseemly language. According to Newsweek, “Anders Vistisen, a Danish member of the European Parliament, has told U.S. President Donald Trump to ‘f*** off’” [see “Trump Told,” January 22, https://www.newsweek.com/donald-trump-greenland-danish-lawmaker-2019001].

* * * * * *

I was stationed in Copenhagen with the U.S. State Department in the mid-1980s, when the Cold War was still raging. As an administrative officer, I had no involvement in political affairs, but still became friends with several members of the large military attache community in our close-knit embassy. They worked closely with the Danish military and NATO officials, and traveled regularly to Greenland—ostensibly to inspect the Thule Air Base, but also, I’m sure, to remind our Soviet adversaries that we still had an interest in keeping Greenland safe for our Danish allies and NATO.

I remember that one of the attaches offered to let me fly to Greenland with one of their regular visiting teams, as an observer, and how disappointed I was at not being able to accept, due to a schedule conflict that kept me from being away from the office for a week. But I found myself fascinated with the history of Greenland and its near-neighbor, Iceland—once a Danish colony and now an independent nation.

During World War II, the United States occupied both Greenland and Iceland, for protective purposes after Denmark itself was overrun by Nazi forces. (The British actually “invaded” Iceland first in 1940 to prevent a German takeover, and soon turned it over to the U.S. forces as guardians—who stationed tens of thousands of soldiers on the island because of its strategic location.)

The long and complicated relationship between Iceland and Denmark—essentially classified as a “personal union” under the Danish monarch, under provisions of a treaty signed in 1918 and set to expire in 1943—meant that Iceland was sovereign for all practical purposes, with its own independent parliament, and a foreign policy of strict neutrality, but still dependent on Denmark for its defense.

Because that treaty expired in 1943, while Denmark was still occupied, Iceland was technically unable to negotiate an extension—and instead daringly declared its total independence, with U.S. forces still stationed at Keflavik Air Base until 1947. U.S. military personnel continued to man the base until 2006, after which it was turned over to the Icelandic Coast Guard. (Iceland has no standing military forces, and depends on NATO for its defense.)

According to the Air Force Times, the situation assumed a more ominous character in 2017, when the U.S. government provided “slightly more than $14 million … to build new hangars to house sub-hunting Navy P-8 Poseidon aircraft … The development at the air station is in reaction to provocations by Russian stealth subs near the GIUK Gap.”

The GIUK gap (Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom) “is a naval chokepoint with large gaps between the three regions. The gap serves as a strategic gateway for Russian subs to access the Atlantic Ocean, and was a major inflection point during World War II for German U-Boats.” The funds came as part of a larger European Deterrence Initiative against Russian aggression, still ongoing as of 2024. [See “US Plans,” https://www.airforcetimes.com/flashpoints/2017/12/17/us-plans-200-million-buildup-of-european-air-bases-flanking-russia/ .]

* * * * * * *

After Denmark was freed from Nazi rule in 1945, Greenland was returned to Danish sovereignty, although the U.S. presence at what became known as Thule Air Base (now Pituffik Space Base, after creation of the U.S. Space Force in 2019), in the far north of the island, complicated matters somewhat—at least until Denmark joined NATO in 1949.

If Greenland does decides to eschew its current autonomous state to seek full independence from Denmark, a major question will be how to defend itself. The island’s gigantic size—more than 2 million square kilometers, nearly 80 percent of which is covered by the icecap and glaciers, and a coastline exceeding 44,000 kilometers in length—makes the prospect economically daunting for such a small population.

There are also more subtle economic factors at play. Although Greenland enjoys a wealth of undeveloped natural resources, its standard of living would certainly suffer in the short term in a post-Denmark environment. It no longer belongs to the EU, although it has a special fisheries agreement with the EU, having been accepted to OCT status (overseas countries and territories) with special association with the body. It formally withdrew from the EU—which it had grudgingly joined as part of Denmark in 1973—after a plebiscite revealed most Greenlanders still opposed EU membership, primarily because over the restrictive fishing rights issue. (A recent move to rejoin has gone nowhere.)

As part of Denmark, Greenland already enjoys NATO protection without charge. If it chooses in the future to join NATO as an independent member—like Iceland, without a standing military—it will likely be obligated to pay for the privilege, and to allow establishment of a larger, permanent NATO-accessible base. For the moment, it currently maintains only its own militarized Coast Guard, under the terms of its 2009 agreement with Denmark.

In essence, Greenland has much to lose—and seemingly, very little to gain—by cutting its longstanding ties with Denmark in an increasingly uncertain world. Trading a benevolent royal ruler for a risky status as an independent island with no guarantees is problematic, but probably inevitable—especially if the cost of maintaining and defending Greenland becomes impractical for a future Danish government.

* * * * * * *

Even after independence, joining the United States would seem like an even unlikelier choice for Greenlanders, given the situation. Language barriers alone make the transition delicate, problematic. English is taught in schools but not widely used outside tourist areas. Most residents speak the official language, Greenlandic, an Eskimo-Aleut language similar to Inuit languages spoken in Canada and Alaska. Only a minority report speaking Danish, although schoolchildren are taught both Greenlandic and Danish, as well as English.

The U.S. welfare state is also far less generous than the Danish welfare state, meaning that Greenlanders would probably lose many automatic benefits they have come to enjoy: unemployment and health care, among others.

Still, a January poll of 416 Greenlanders on the subject of joining the United States—conducted during Donald Trump Jr.’s visit to the island—indicated that a surprising majority of the respondents, 57 percent, appeared to favor some kind of union with the United States. That stunned many observers. [See “Poll finds majority,” https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/us/poll-finds-majority-of-greenland-respondents-support-joining-the-u-s-will-the-largest-island-become-american-territory/articleshow/117208207.cms?from=mdr ].

Danish leaders insist, rightly, that it is up to Greenland to decide, period. A plebiscite must come first. Denmark is prepared to let the island go if and when a majority of its voters ask for independence. But in the meantime, “no sale” to the United States—despite President-elect Trump’s ominous threats that the U.S. military could “take” Greenland by force, amid the ludicrous prospect of invading territory belonging to a friendly NATO ally.

King Frederik and Queen Mary do not control the political process. But their interest in Greenland is intensely personal. They have visited Greenland several times, including a sledding trip in 2004, just after they were married, and most recently with their children in 2024, after their coronations. The Queen’s Mary Foundation has won her a devoted following among the people there.

In a 2024 video documentary [below], they appeared to be extremely fond of the people and customs, dressing in local costumes and interacting easily with residents of both the capital and the villages.

It is clear that Frederik X and Mary will long retain their [personal attachment to the island, even when it is no longer in their royal domain. How Frederik X might revise his next royal coat of arms in that event to reflect its new status, however, is anyone’s guess.

Next time: Chronicling the history of Union Institute & University

Thank you, a very interesting read. I am just finishing a piece on the 1917 transfer of the DWI. I will send you a link when its done if I may.

I understand that as well as the $25 million, the US ceded any rights they had to Greenland under that treaty. From what I have read, it sounds as if that was some sort of a fig leaf for Danish politicians to argue that this was about consolidating overseas territory as well as selling it.

I have also been reading about a proposal that was doing the rounds in Danish circles at the time to do some sort of grand three way swap where the US took the DWI and Greenland, while giving Germany part of the Philippines in exchange for the return of Schleswig! The suggestion was that the British at the time would probably have blocked any transfer of Greenland to the US; one of many reasons why it never got off the drawing board. Those were the days!

Given your knowledge and experience of US/Danish diplomacy, it would be great to get any further insight you have on all this.

Thanks again