Foreign affairs in a crazy mixed-up world

Crypto-capitals, falling dictators, impeachment attempts

I recently read that a long-shot candidate for the presidency of Suriname is pledging to make bitcoin (cryptocurrency) essentially the national currency of her country if she is elected in 2025. Frankly, I was a bit baffled—the Surinamese economy is already a disaster zone, and the local dollar, introduced in 2004 to replace the laughable Surinamese guilder, was valued at less than 3 U.S. cents last month.

So how could a currency no one can see, hold, or really understand make a dreadful situation any better? Granted, it could not make the situation much worse—inflation in the tiny South American country is rampant, estimated by some sources at 50 to 60 percent annually.

I do not understand the mechanics of cryptocurrency. It all seems a bit fishy to me. I see that it recently crossed the $100,000 level in value, which sounds good—but its price collapse not so long ago (below $20,000 in 2023) makes it seem suspiciously volatile to me as an investment—and never as legal tender.

But Maya Parbhoe’s reasoning is refreshing, at least: she wants to root out widespread corruption by making government more transparent. The successful young businesswoman, 36, has already started three successful new businesses—inheriting vision and acumen, if nothing else, from the defunct empire started by her grandfather and carried on by her murdered father, Winod Parbhoe, killed by hit men in 2001.

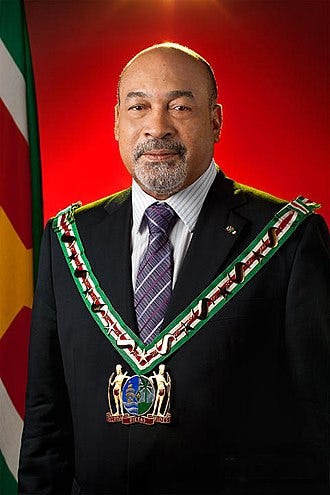

Maya Parbhoe, candidate for president of Suriname. Photo courtesy Bitcoin Magazine

I served as a Foreign Service Officer at the U.S. Embassy in Paramaribo for about two years (1989-1990), when the country was still in the thrall of former dictator Desi Bouterse, and the economy was an absolute basket case. I never shopped at any of her family’s businesses back then—at astounding black market prices (20 Suriname guilders to 1 US dollar), I refused to buy anything but perishable food items—but they were certainly well-known and wealthy, before they lost it all.

Bouterse was never known as whiz at economics, and the country’s economy was more like that of Mars than any civilized Western nation when I arrived. But even after his party lost control of parliament, and he stepped back to control just the military, he refused to stop dabbling in politics—and strangely enough, was resurcceted and elected president for 10 years. Incidentally, he is now a fugitive from justice after refusing to surrender himself last year to begin serving a lengthy sentence for murders committed during his 1980s stint as strongman.

He could conceivably run for president again himself, if his party regains control of Parliament as some expect, in spring elections —and he receives a pardon. Reportedly now in hiding with government connivance in then country’s vast jungle interior, he will reappear only when it is convenient. Vice president Ronnie Brunswijk, a convicted drug smuggler, may also decide to run, just for fun.

Former Surinamese president Desi Bouterse. Public domain photo

Meanwhile, according to the Guardian newspaper, Suriname’s current president, Chan Santokhi, is gearing up to seek his own reelection in May with a promise worthy of Huey Long, the fabled populist U.S. politician of the 1930s. Instead of a chicken in every pot, though, Santokhi recently “announced a program of ‘royalties for everyone’ as the South American nation plans for a boon from recently discovered oil and gas reserves”—a onetime payment of $750 to every citizen (you can see that article at “Royalties for everyone,” https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/nov/25/suriname-president-oil-wealth).

Current Surinamese President Chan Santokhi. Public domain photo

So the field may already be too crowded for a newcomer like Parbhoe. Depending on who you talk to, her candidacy is either a huge publicity stunt or a serious attempt to rewrite political history in the former Dutch colony. She has no real political party or any real influence, and most observers doubt she could win even a handful of votes in the country’s notoriously chaotic parliament.

But her expressed admiration for another bitcoin enthusiast—the president of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, who founded a whole new party and won the 2019 election at age 37—and was reelected in 2024—and then made bitcoin legal tender in El Salvador, in a controversial move that briefly threatened to bankrupt the country.

El Salvador President Nayib Buekele. Public domain photo

While it is technically legal to use bitcoin and other crytocurrencies in many countries, including the United States, only one other country in the world has made it actual legal tender: the Central African Republic. That means it must be accepted under a country’s laws “if offered in payment of a debt,” according to the definition offered by Oxford Languages. (The U.S. Department of Treasury, meanwhile, currently defines “bitcoin as a convertible currency with an equivalent value in real currency or one that can act as a substitute for it.”)

Parbhoe would like to begin paying Surinamese state employees in sats—short for satoshis, the smallest unit of the bitcoin cryptocurrency, named after its founder. She believes that implementing its use as legal tender would immediately lower prices nationwide—although it would severely complicate its day-to-day dealings with China, one of the few nations that bans it completely (the other is Saudi Araba.) Suriname already owes Chinese state-owned Exim Bank some $476 million, of which $140 million was in arrears in November, when the two nations agreed to reschedule debt repayments. Imagine how happy China would be if Suriname tried to pay its loan back in anything but U.S. dollars …

So keep your eye on Surinamese politics. [See the full article at https://bitcoinmagazine.com/politics/meet-maya-parbhoe-the-pro-bitcoin-presidential-candidate-who-wants-to-save-suriname ].

* * * * * * *

The sudden disappearance of Syrian president-for-life Bashar al-Assad last week reminded me of the similar collapse of the regime of Haiti’s clownish dictator for life, “Baby Doc” Duvalier, in 1986, who succeeded his even more savage father, Francois “Papa Doc,” in 1971. I had forgotten that the ridiculous Jean-Claude—jeered at as doltish by almost everyone, even in France, where he resided in exile—actually returned to Haiti in 2011, long since divorced, and died there, unmourned, in 2014, reportedly working on a memoir no one wanted to read.

The Duvaliers, in better days. Courtesy People Magazine

Duvalier lived in luxury with his wife Michele, dubbed a “Dragon Lady” by tabloids, offering imported French champagne and caviar to guests, a depressing contrast to the squalor he forced upon most of the island; apparently he saw nothing incongruous about then taking his guests on guided tours of the capital. According to Wikipedia, during the younger Duvalier’s reign, “The National Palace became the scene of opulent costume parties, where the young President once appeared dressed as a Turkish sultan to dole out ten‑thousand‑dollar jewels as door prizes.”

My wife, a former flight attendant for Air Jamaica, told me she once visited the city on a promotional tour and was horrified at the shocking conditions she saw outside the presidential palace—beggars everywhere, no food—and the apathy displayed by her guide. Afer voicing her own sentiments about the disparity, she received no party favors—nor any invitations to return. Friends of mine who served at the embassy in Port-au-Prince bore the details out.

I visited that pitiful island just once—a daylight stopover en route to Miami from Suriname, on a diplomatic courier run, in early 1990, when the airport was under siege by machine-gun-armed snipers, during the brief term of newly-appointed President Ertha Pascal-Trouillot, who stepped down in 1991.

The chaos then prevailing in Port-au-Prince was nothing compared to today’s horror show, of course. It was only a refueling stop, and no passengers were being allowed to board. But the warning I received from my commercial pilot when I disembarked to inspect the cargo hold’s door, making sure no one troubled my diplomatic pouch—”whatever you do, do not step outside the shadow of the plane”—was basically enough to convince me not to want to visit again. He pointed up at the terminal’s roof, where a half-dozen military snipers had guns pointed toward the plane, ready to fire at any misguided asylum-seeker or trouble-maker, I guess. I did not dare take a photo.

Meanwhile, back in Damascus, Bashar al-Assad, whose extraordinarily lavish hillside palace overlooking the city was “opened” to the public days after he fled to safety in Moscow, was an obscure ophthalmologist taking graduate courses in London when summoned home by his father, longtime dictator Hafez al-Assad, in the 1990s. His older brother, the first heir apparent, was dead, and it was now his turn in the barrel. He succeeded his father in 2001.

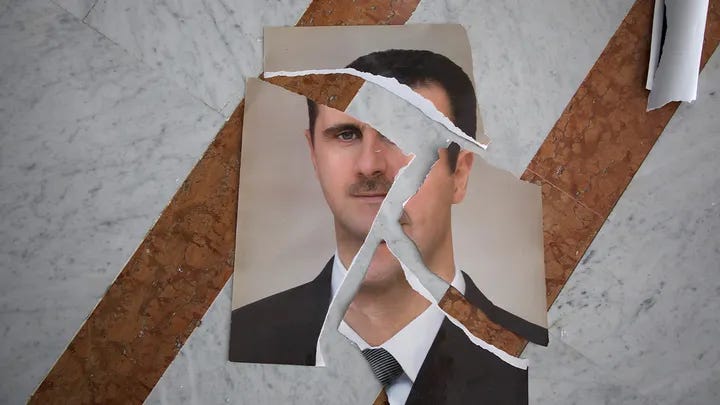

A torn portrait of Bashar al-Assad found inside the Presidential Palace in Damascus. Courtesy Fox News.com

I don’t think Bashar will be returning to Damascus 25 years from now, except in a pine box. He is as detested by almost all Syrians as much as his late father was, on general principle—and having murdered 500,000 countrymen during a decade-long civil war that saw him condone use of chemical weapons, deserves to hang if he does come back. In my opinion, he may soon wear out his welcome with Vladimir Putin, his former benefactor and military guardian, especially if he expects to live in a house like the one he just lost.

A lifelong friend of mine from Kingston days, John Clarkson, used to regale me with stories of his brief life in Damascus under Bashar’s father, on his next tour after Jamaica. Back then John, who passed away in 2020, was a junior economic officer—and as low man on the totem pole, was chosen to be expelled by the Syrians in a tit-for-tat dispute between the two governments. He had done nothing wrong, but someone had to be sent home. So he went, persona non grata, and glad of it. I always wondered if he volunteered …

John Clarkson, right, with me at the White House in 2016, as tourists. Author’s photo

It was actually something of a badge of honor. John went on to a long and successful career with the State Department, retiring in 2015 after serving his last post in Muscat, Oman. He saw many of the world’s fascinating places along the way—among them New Zealand, Taiwan, Malaysia, Uzbekistan, and Finland, where he and I once again crossed paths during my last assignment to nearby Riga, Latvia, in 1992. (I left the State Department for the private sector in 1997.)

As a last gesture of good will to Syria, Assad thoughtfully looted the public treasury, leaving the country completely broke, as well as in ruins. Good guy, to the end. I don’t hold out much hope that Syria will become a thriving tourist destination anytime soon, or that it will sustain a democratic government for very long, with his violent recent history. But I hope many of the millions of refugees will get a chance to come home again, this time without the bloodthirsty al-Assads in charge—and sorry that John did not live long enough to see it happen.

* * * * * *

I have never been to South Korea, althiugh I have heard many good things about Seoul and have many friends who speak highly of it as a place worth visiting. But I am not impressed by its increasingly unstable political situation, or by the quirky behavior of its current president, Yoon Suk Seol, who inexplicably declared martial law last week, and briefly banned political activities of any sort.

President Yoon, a conservative firebrand in office since 2022, was quickly persuaded to retract his doomed declaration, and survived an initial attempt to impeach him, with many legislators hoping he would simply resign and spare them the public spectacle of a trial. From what I have seen in the news recently, another more serious attempt is now being mounted as I write. Even the ruling party has turned against him now. But he is adamant about not resigning, and prepared to “fight to the end.” Sounds eerily familiar …

Current South Korean President Yoon Suk Seol. Public domain photo

I do not claim at all to understand South Korean’s turbulent brand of politics, but gather that Yoon believed North Korean sympathizers were becoming much too powerful—and the only way to stop them was to declare martial law, and try to seize the parliament building. He was forced to take it all back—sort of.

This in a country that has already impeached one quirky president in 2016—Park Geung-hye, the first woman to be elected there—and then tried and convicted her on corruption charges, imposing a total prison term of 33 years, before she was pardoned in 2021 by her successor. She was, of course, the daughter of the infamous South Korean military dictator, Park Chung-Hee (ruled 1961-1979), who was assassinated; her mother was also assassinated in 1974 (in a failed attempt to kill her husband).

Former South Korean President Park Geung-Hye. Public domain photo

I suppose that South Korea’s relatively brief era of democracy and dealing with an unstable northern neighbor have taught it very little so far about patience or restraint. Its first democratically elected president (Noh Tae-Woo) took office only in 1987, and its first civilian president only in 1993 (Kim Young-Sam).

Perhaps, with time, the situation will calm down a bit and stabilize. I hear, however, that partisanship in Seoul is as strong and poisonous there as in the United States, which is no comfort at all.

I wish them well. But I am not inclined to vacation there for a while.

Next time: More crazy foreign affairs