And now, for something completely different ...

Riding the Death Railway in western Thailand--and surviving elephants and a bus ride in Bangkok

I was still a commissioned officer in the U.S. Foreign Service in 1991, when Margaret and I made our only trip to Thailand. We were living at the time in Singapore, where I was posted as a regional personnel officer for Singapore, Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia, and Bandar Seri Begawan in Brunei. In previous posts, I have talked about our time in those three cities and my professional duties in each.

Bangkok was not far away, of course, and when I was called there for consultations in the fall of 1991, I was thrilled to be able to spend a few days sightseeing in this mysterious, bustling city, then home to about 6 million souls—or roughly half its size as I write 30 years later. Many of my Embassy friends had already tried to interest us in taking a long weekend in Phuket, in southern Thailand, which they saw as the ultimate freewheeling beach destination for Western tourists, but I was more interested in sightseeing and history than partying.

I have always envisioned Thailand as something out of The King and I, the musical motion picture based on the adventures of Anna Leonowens and the King of Siam. I knew, of course, that it was dramatized and exaggerated, but I half expected Yul Brynner and Deborah Kerr to come dancing along the streets of Bangkok at some point. I had long heard tales from friends who served in the U.S. military in South Vietnam about the plentiful attractions available on R&R in Bangkok.

But when Margaret and I got there in 1991, we did not head for the red-light district. What we found instead were plenty of elephants from a distance, and up close, tuk-tuks—the somewhat odd three-wheeled bicycle-like transport that served mostly tourists.

We did the usual tours, visiting every statue of Buddha we could find at Wat Pho—including the marvelous reclining golden Buddha, 46 meters from end to end. It was just breathtaking, the kind of statue you could stand and watch for hours.

The extraordinary reclining Buddha statue at Wat Pho, Bangkok. Photo by Phillip Maiwald (Nikopol) - Own work, Wikipedia

But of course, we only had three days and a lot of ground to cover. We were fortunate enough to have one friend posted at the Embassy—Judy Cefkin, who had joined the Foreign Service at the same time I did in 1983, and gave us pointers over lunch just after we arrived. Margaret, the irrepressible tourist, took advantage of my official absence in consultations to plan a trip to the only other part of Thailand I knew anything about, again from my childhood in movie theaters: the Bridge on the River Kwai, where I suspected I might find at least a reference or two to Sir Alec Guinness, who was still alive in 1991.

But Sir Alec was not on the ticket that year. So Margaret arranged for us to take a ride on the Death Railway instead. Just getting tickets was a bit of a challenge, but for my globe-trotting tourist wife, a former flight attendant and hotel concierge, her will found a way.

A modern Thai Railways train rounding a curve at death-defying heights. Photo courtesy Viator.com

The Death Railway was literally that. According to Australian estimates, perhaps 100,000 workers died building it in the early 1940s. They were mostly Malaysians, but included 12,000 Allied prisoners—Brits, Australians, Americans, and Dutch soldiers forced into service by the Japanese occupiers. In addition to malnutrition and physical abuse by overseers, malaria, cholera, dysentery, and tropical ulcers took their toll.Construction of the Thai-Burma Railway, which originally ran for more than 400 kilometers (258 miles) from near Bangkok to Thanbyuzayat, a port in Burma (now known as Myanmar), took more than three years.

Today’s remnant of the railway line runs for about 80 miles (130 kilometers) on the Thai side, and despite the downright alarming views out the windows at some stretches, was still a popular attraction 50 years later. Neither Margaret nor I was daring enough to lean out the windows, as a couple of tourists have done in recent years—with understandably fatal results, one particularly foolish New Zealander attempting a selfie, as he slipped and fell after opening a train door in 2022.

Reckless tourists caught snapping away as the Death Railway plows on. Public domain photo

More than 600 bridges were required, most far shorter then the famous Bridge on the River Kwai. We did not actually cross the bridge, on foot, but were able to see it from where we stopped at Kanchanaburi to visit the JEATH War Museum. That museum, opened in 1977 on the grounds of an ancient Buddhist temple, honors 7,000 war dead from the six countries involved —Japanese, English, Australian, American, Thai, and Holland—many of whom are interred at the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery, which holds relocated graves from other burial sites from the period, one of three Commonwealth War Graves Commission sites open to tourists today.

[Check out the URL for the Commission:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/2017100/KANCHANABURI%20WAR%20CEMETERY]

The sign outside the JEATH Museum, Kanchanburi. Public domain photo

The bodies of the 133 Americans who died—about 20 percent of those captured and commandeered—were repatriated after the end of World War II. After touring the JEATH Museum, which contains a reconstructed Japanese prisoner camp, I was frankly amazed that the death rate was so low. The conditions were abysmal—and the torture methods used were unspeakable. At the end of World War II, a total of 111 Japanese military officials were tried for war crimes for their brutality during the construction of the railway, with 32 of them sentenced to death.

The most famous bridge built with their brutality—Bridge 277, at 322 meters in length—was built over a stretch of the river then known as part of the Mae Klong River. According to Wikipedia, most “of the Thai section of the river's route followed the valley of the Khwae Noi River (khwae, 'stream, river' or 'tributary'; noi, 'small.' Khwae was frequently mispronounced by non-Thai speakers as kwai, or 'buffalo' in Thai). This gave rise to the name of ‘River Kwai’ in English.”

There were actually two bridges built here by slave labor—a wooden bridge followed by a second, ferro-concrete bridge—that were damaged by Allied bomb strikes in the winter and late spring of 1945, and finally put out of commission completely as the War wound down. The remaining bridge was closed for about a decade before being reopened in 1958. It is interesting to look at, but not spectacular.

The Bridge on the River Kwai at Kanchanaburi, Thailand, as it looks today. Public domain photo

An undated photo of the damaged bridge, probably taken in spring 1945. Public domain photo

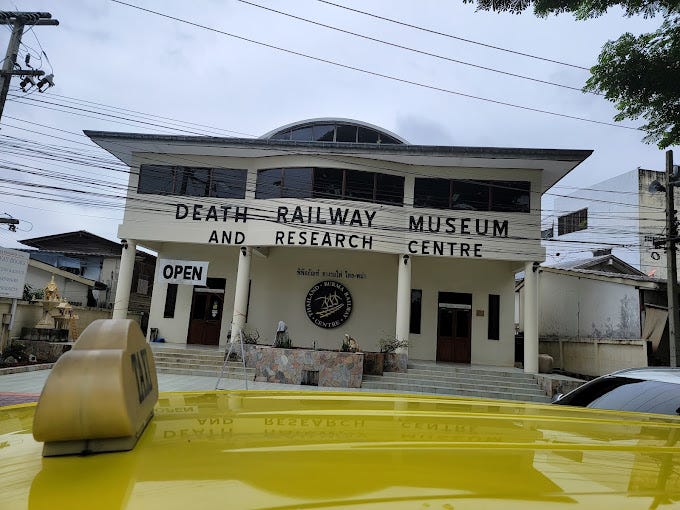

The Death Railway Museum and Research Centre today. Public domain photo

We were, of course, not able to get to the Burmese border—both for political and logistical reasons—too far for a one-day trip, all we had time for. So we never made it Burma. I am told the Burmese side of the railroad is not as well maintained, and have read elsewhere that it was never possible to cross there, except on ferries.

Visiting the Bridge on the River Kwai was an uplifting but sobering experience, especially at the sight of so many Japanese tourists scattering flowers at the Kanchanaburi Cemetery. Unlike the Allied section, the Japanese section, I was told, was poorly maintained, but the visiting tourists seemed to be honoring all the dead, not just their own. I wondered …

Margaret and I made it home to Bangkok exhausted but in one piece, although we did have one late-night surprise waiting for us. The bus transporting us back to our hotel was forced to stop in heavy traffic on top of a railway crossing, where it seemed to take forever for the traffic ahead of us to clear. We had window seats on the left, and began to observe what turned out to be an oncoming freight train, far off in the distance, but closing in on us at normal speed, not slowing down.

Was I dreaming? Was this a nightmare? Had the Death Railway followed us back to Bangkok? I was still debating whether to tell the driver we would get off and wait on the other side of the crossing to be picked up again, when the traffic jam suddenly cleared up. A small miracle of sorts …

Next time: Life on the open road: My visit to the Badlands and Medora, buffalo and all …