And now for something completely different ...

Part 1: From paradise to hell, and back again ...

The author’s photographs of Devil’s Island from the more serene Ile Royale.

The epic movie Papillon easily captured my imagination in 1973. The somewhat fictionalized version of Henri Charriere’s 1969 book—starring Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman—about two men’s daring escape from life as tormented prisoners in the Salvation Islands seemed a far cry from my sheltered life as a journalist back then. Officially called the Iles du Salut, one of the three, Devil’s Island, best symbolizes the 100-year reign of terror imposed on French criminals and others deported to the New World for their sins—sometimes for life, sometimes for death.

The prison itself was closed in 1953, shortly after I was born, and it remained to me a mysterious other-worldly place, which I knew historically only as the temporary home of the famous Alfred Dreyfus, a political detainee for whom the famous novelist Emile Zola had once penned the infamous phrase, “J’accuse,” in an open letter to the French President in 1898—and which later led to the astounding retrial of Dreyfus and eventual exoneration, well, sort of.

In 1973, all this untraveled Tar Heel knew about the nearby Caribbean Sea and Atlantic Ocean was confined to a weeklong honeymoon in the far more engaging U.S. Virgin Islands. It was only after I became a U.S. Foreign Officer a decade later in 1983, and began revisiting the world map as I pondered bids for my foreign postings, that I set the wheels in motion for actually visiting the site as a tourist. My first choice for an embassy job was a true Caribbean paradise—Kingston, Jamaica, as a consular officer—followed by a European fantasy, Copenhagen, Denmark, as a general services officer.

We do not have an embassy in French Guiana, I should note here—it is an overseas department of France, the only European stronghold left in South America—so it was not on the list when it came time to pick a third posting, after a brief domestic job in the State Department’s press office. I picked the country next door, a former Dutch colony called Suriname. A few years, earlier, its more westerly neighbor, Guyana, had gained worldwide notoriety as the grisly scene of Jonestown, where so many Americans had perished in a mass suicide/murder perpetrated by the fugitive sociopath, Jim Jones.

In early 1989, I was posted as the administrative section chief at our embassy in Paramaribo, the capital, and almost immediately regretted my stupidity in volunteering for what turned out to be a nightmare—not the adventure I had expected. Suriname was more infamous for its military dictator’s exploits after being granted independence than for anything else, and not much of a tourist destination by any standard (except for wild-game hunters): a basket case economically, with a struggling and inept, corrupt distortion of democracy, and only one hotel worth considering at the time, beset by a nearly laughable rebellion, and more than a little complicated to get to.

The only international airport, Zanderij (ZAN-duh-ray), lay an hour outside the city in a jungle, and the road to and from was a sort of demilitarized zone—separating the government-held territory from the eastern area led by the rebel leader, Ronnie Brunswijk—a former military guard to the dictator, Desi Bouterse, and in a twist worthy only of Surinamese buffoonery, elected its vice president in 2021, second only to the ludicrously inappropriate earlier elections of Bouterse as president. It was like a National Lampoon send-up. Or maybe, Mad Magazine in real time.

Expanded on the site of a far smaller airport nearly 50 years earlier by the United States as a World War II military jump-off point to West Africa, its only incoming commercial planes—Dutch KLM and Suriname’s offshoot, SLM—for some reason, only landed after dark, just before midnight. The long dark drive into the city was at best, daunting. (Armed bandits were plentiful, apparently, and the government was useless at providing any security; a sort-of-handshake agreement with the rebels was in place by day …)

The local economy was in free fall—the Surinamese guilder pegged to an all-but- fictitious exchange rate—the same as the Dutch guilder, as I recall, about 2 to 1, and everything locally available sold at black-market prices (20 to 1). But in its infinite wisdom, the U.S. government required its employees to buy local currency at the established rate, and then pay black-market prices for the little produce, local beer—a dreadful concoction called Parbo, brewed with way too much formaldehyde, leading to terrible headaches—and fresh milk that were readily available. We did have a small commissary, which provided nonperishable staples shipped in duty-free—and could also ship in our own consumables—for use in Western-style housing, with full-time guards posted outside—in the pleasant but gradually deteriorating suburban neighborhoods previously once built for expatriate employees of the fading, soon-to-collapse bauxite-aluminum firm, Suralco.

But the Embassy was located in a frequent-flood district—an inch monsoon season rain backed up the sea-level city’s storm sewers and soon sent waves lapping at our front door. The local water was not considered drinkable—thanks to cross-contamination from poorly-maintained sewer pipes—so we filtered and treated water for use in our home kitchens. The job itself was unforgivingly stressful and relentlessly exhausting, thanks to the chaotic workplace inherited from my predecessor, who had left under less than ideal circumstances—and five months later, I was already burning out. Even the occasional free trip back to the U.S.—as a diplomatic courier to Miami, via Air France and Eastern Airlines, via Haiti—was only a minor vacation.

I was about to celebrate my 40th birthday alone. I had a stray dog but almost no social life, to speak of. My current wife, still working in Washington, had not yet moved to Paramaribo, so we met every few months in Miami. Most days I worked, went home, ate my own cooking, and got up the next morning, went back to work—at 7:30 a.m., the worst joke of all, to match the fiction of the local economy, where even government workers only clocked in before leaving for their “real” jobs. There were occasional parties—Embassy buddies did take pity on me occasionally, too, and invited me for dinner, but eating out was almost an unaffordable.

I was seriously reconsidering my choice of careers. Fond memories of Jamaica and Denmark were not enough to keep my wilting interest level up. So I thought, what the hell? I am not staying here and don’t have time to fly back to the U.S. Do something new, something you will never do again—I was still a bit of a daredevil back then—and after a quick domestic flight to Cayenne, the French Guianese capital, I soon found myself on a short but perilous 10-mile sea journey, to Ile Royale from Kourou, the town where the French built their modern space-launch complex.

Map of the three Salvation Islands,

off the coast of French Guiana, in South America.

I am told that 50,000 or more tourists come each year to the Salvation Islands—or more specifically, to Ile Royale next door, the largest and highest of the trio—not to Ile du Diable, which one can easily see across the narrow, 100-meter-or-less channel, but which is almost impossible to set foot on these days. Boats cannot land there; a sort of cable-car system once connected the two islands, just over the deadly currents and the heads of murderous sharks whose ancestors used to devour unlucky escapees. It was used almost exclusively, at first, to house inmates with leprosy (Hansen’s disease), then became, ironically, a home for political prisoners. Misbehavers on Ile Royale were transferred to The Seclusion cells, on nearby Ile Saint-Joseph.

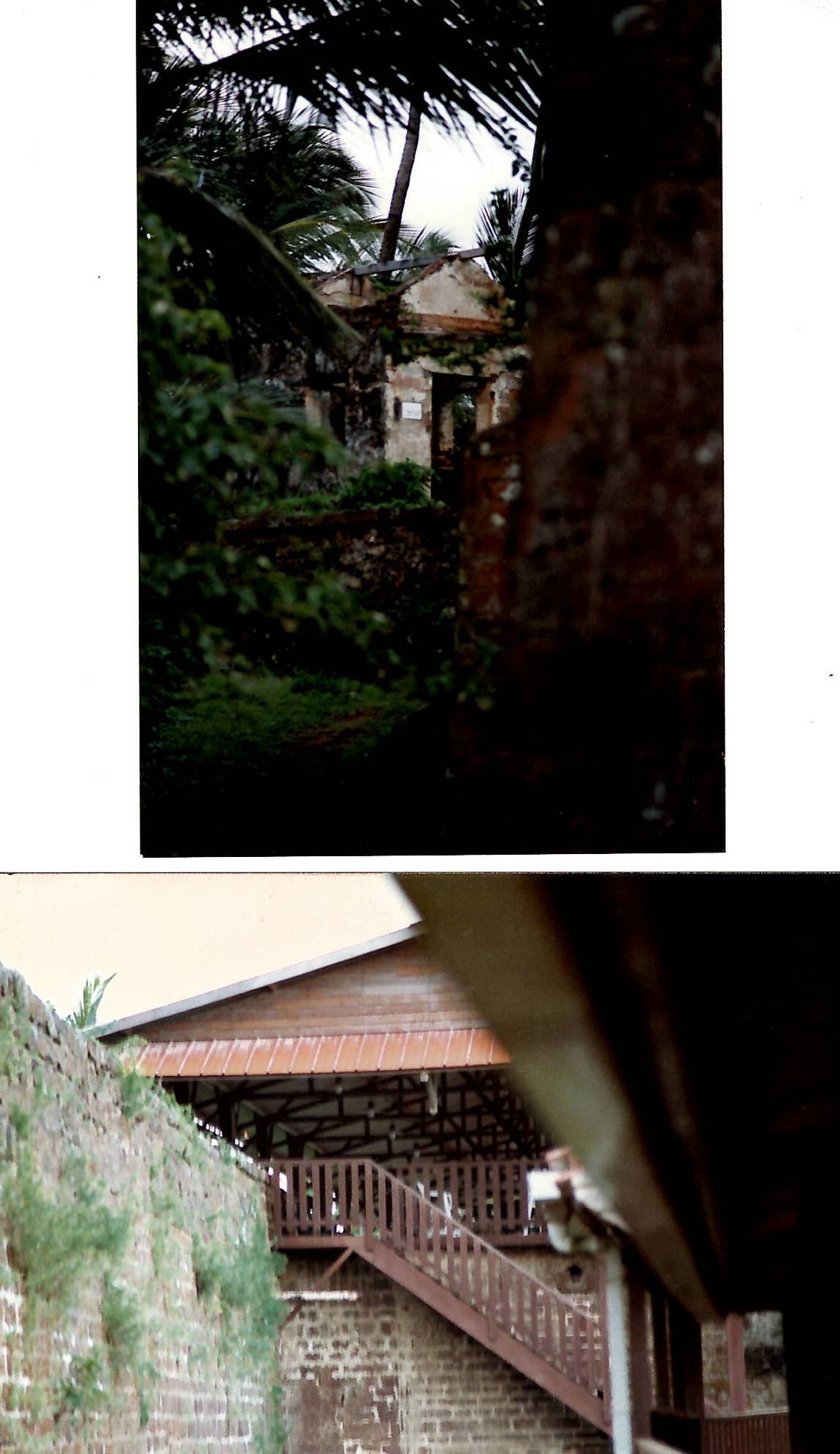

Crumbling prison ruins (top) and the view from spartan accommodations of a small tourist hotel (bottom).

The less-than-10-mile trip over turbulent water to Ile Royale took almost an hour, and most of my fellow tourists spent the voyage retching over the sides of the boat. I do not suffer from seasickness—small comfort, when almost everyone else around you does—and spent much of the time thinking instead about what I would find during my 24-hour stay on land. It simply had to be more interesting—and memorable—than the unfortunately quaint, miserably dilapidated Paramaribo had already proved to be. I really needed a change …

And it was actually diverting, in an odd sort of way. The sites still left standing on the island, mostly condemned, were closed off to tourists. We were allowed to walk around on our own, take photographs, breathe the fresh salty air. It was quite hot, as I recall, in mid-June, but there was a nice sea breeze. The open-air hotel, such as it was, was spartan but comfortable, with ceiling fans. Strangely enough, I cannot recall what I ate. We must have had some sort of tourist cafeteria, but my new German friends and I were probably too busy chatting to notice what we were being served: probably sandwiches and beer.

I think we were all thinking instead about how exciting we could make it sound to those who had only seen the movie, and never got there in person. I corresponded briefly with my German friends once I left. Slept like a baby. I felt rejuvenated, if only briefly. I felt, incidentally, as if I were going back to prison myself … not escaping from prison … as I boarded the departing boat.

Dreyfus, of course, was housed on the smallest island, the “real” Devil’s Island—the one we could see but not go to. You can still see his solitary hut along the shore of the palm-infested shore. He was not a typical detainee—most were violent criminals of one sort or another, and only those who were punished for extraordinary misbehavior went to cells on the third island, Ile Saint-Joseph, for solitary confinement and reeducation. (Murdering another inmate, however, was rarely even reported … or punished …)

Over the century it existed, perhaps as many as 70,000 or more prisoners went to the Cayenne penal colony, as it was called, and its brutal reputation was well-deserved. Only about 5,000 even survived the many horrors of the journey there or the hell they entered on arrival, or the harsh life they were then forced to lead in French Guiana after their formal sentence concluded.

When the French government closed the penal colony completely in 1953, few mourned its departure. Even today, its memory rivals that of the Soviet gulags for the sheer inhumanity displayed to the men who endured it—and for whom death was often a welcome escape, almost always the only escape. Escape, Charriere and a handful of others aside, was all but impossible. Prisoners who died were thrown to the sharks …

And for those not well-read on the Dreyfus affair, here is a brief excerpt from the Encyclopedia Britannica:

In 1894 Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a career army officer of Jewish origin, was charged with

selling military secrets to the Germans. He was tried and convicted by a court-martial and

sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil’s Island … But secrets continued to leak to the

German embassy in Paris, and a second officer, Major Marie-Charles-Ferdinand Esterhazy,

became suspect. The chief of army counterintelligence, Colonel Georges Picquart, eventually

concluded that Esterhazy and not Dreyfus had been guilty of the original offense, but his

superior officers refused to reopen the case. … In 1898 some of the army’s most persuasive

documents against Dreyfus were discovered to be forgeries. Esterhazy promptly fled to

England. In a second court-martial, late in 1899, Dreyfus was again found guilty but with

extenuating circumstances; he received a presidential pardon and was later (1906) vindicated

by a civilian court.

And what of the world-famous author, Henri Charriere, the convicted murderer whose book had first captured my imagination? Born in 1906, convicted in 1931, and soon “transported” to French Guiana, he did live in Venezuela for years after his final escape—in 1944, during World War II—and died of cancer at age 66, in Madrid, Spain, the year the movie based on his book came out. He had finally been pardoned by a French court in 1970, and along the way, had become a successful restaurateur. He became even wealthier on book royalties.

But how much of his thrilling story was even true? Many of the details he recounted turned out to be of doubtful authenticity, and barely true even for him, apparently the stuff of compiled anecdotes told him by other escapees. Official French documents released after his best-selling book indicated he had never been imprisoned on Devil’s Island, or even on Ile Royale, at all—only on Ile Saint-Joseph, for misbehavior and a previous escape from the mainland facility near Cayenne.

So Papillon, however exciting, turned out to be pure Hollywood: mostly fiction—semi-biographical fiction, perhaps, but still a terrific film—and true or not, a great story!

Next time: Part 2: I finally learn not to smoke in public …