An unusual presidential election in 1900 features old faces and new partners

McKinley and Bryan in rematch, with new running mates

The 1900 U.S. presidential election—technically the last of the nineteenth century—might well be considered the first truly modern one in American political history, even without modern technology and communications.

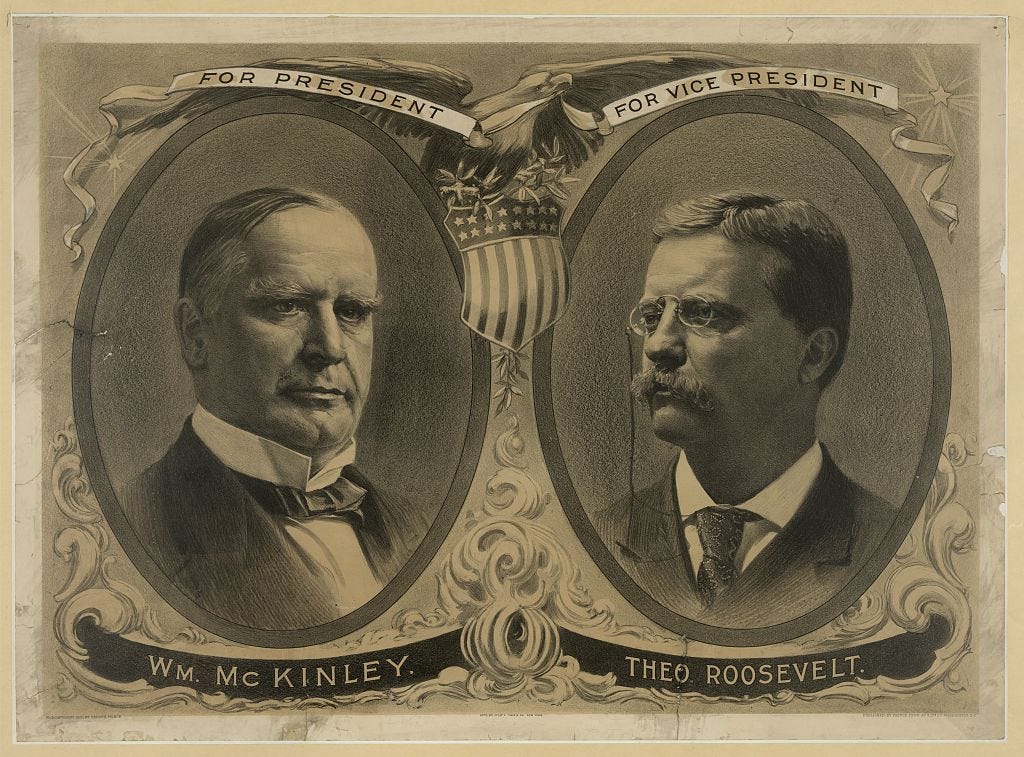

William McKinley, the 1896 winner, who had successfully prosecuted the brief Spanish-American War during his first term, was renominated by the Republicans. William Jennings Bryan, the former Nebraska congressman and famous Populist candidate in 1896, was renominated by the Democrats.

Both men were familiar faces. But both had new running mates at their side in 1900. For the President, the sad death of Vice President Gus Hobart in 1899 had left him at the mercy of party strategists to name a successor; the most popular candidate turned out to be the rambunctious and headstrong young governor of New York, Theodore Roosevelt.

For the Democrats, the situation was somewhat more complicated. Bryan’s running mate in 1896—Arthur Sewall, a wealthy shipbuilder from Maine—was still around in 1900, but had fallen from favor among the Democratic leadership; in uncertain health, he died of apoplexy in September 1900, two months before the election. Determined to build a stronger ticket in the rematch with McKinley, Bryan and his strategists settled instead on one of the party’s most popular figures, former Vice President Adlai Ewing Stevenson of Illinois, who had served during President Grover Cleveland’s second term.

William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, Republican candidates in 1900. Courtesy Library of Congress

Presidential campaign button, William Jennings Bryan (left), Adlai E. Stevenson,

Democratic candidates in 1900.

It was among the most unusual pairings ever—age-wise, at least—of candidates for either party. At just 41, Roosevelt—he turned 42 the week before the election—was almost young enough to be the 57-year-old McKinley’s son—and looked even younger. If elected, he would become the nation’s second-youngest vice president ever (John C. Breckinridge, inaugurated in 1857, was the youngest, at just 36.) But even so, Roosevelt was almost two years older than Bryan, once among the youngest members ever elected to Congress—at age 30, in 1890; six years later, he had barely met the Constitutional requirement (35) to become president the first time he ran. If elected this time, he would turn 41 two weeks after taking office in 1901.

Stevenson, on the other hand, was 65, old enough to be Bryan’s father—and his bushy white mustache made him look even older than that. If elected in 1900, he would have been among the oldest vice presidents in history. He had briefly been considered by some as a contender for the Democratic nomination to succeed Grover Cleveland, before Bryan was selected in 1896. Having served as a state’s attorney in 1865, Stevenson’s political career had already spanned 35 years in 1900, or nearly Bryan’s entire lifetime, and the two were somewhat ill-suited as running mates.

But their age disparities aside, all the candidates faced other statistical historical challenges. Incumbency was generally a positive factor, making McKinley at least a slight favorite after a successful first term, having just won a popular war against Spain, and the U.S. economy considered reasonably strong. Republicans had held onto control of Congress in the 1898 mid-terms, but had a somewhat smaller majority in the House than after 1896.

But there were no certainties in political life, and the charismatic Bryan was certainly no pushover; he had polled just 600,000 fewer votes out of 14 million cast in 1896. For all its positive aspects, incumbency was always a mixed blessing; no sitting president had been reelected in nearly 30 years, since Ulysses S. Grant had won his second term in 1872. (Cleveland had won a second term in 1892, but only after losing in 1888.) Meanwhile, no former vice president had ever run again to seek his old office under a different nonconsecutive president; George Clinton (1805-1812) and John C. Calhoun (1825-1832) had each served two terms, but each was elected alongside two different back-to-back presidents. Only one ex-vice president—Millard Fillmore, who had succeeded Zachary Taylor as President in 1850—had even tried later to run again for either office (as president, unsuccessfully, on a third-party ticket, in 1856). James Buchanan’s sitting vice president, John C. Breckinridge, one of three Democratic factional candidates in 1860, lost that year to Republican Abraham Lincoln.

Yet other historical precedents did seem to favor McKinley in this race. Like Republicans Grant in 1872 and Abraham Lincoln in 1864, both of whom won second terms, McKinley chose a different vice president in his second try. And generally speaking, incumbency was a good quality; only four of 12 presidents in U.S. history so far had lost their bids for a second term—John Adams in 1800, John Quincy Adams in 1824, and Martin Van Buren in 1840 had lost toss-up races to their same earlier opponents.

The only loser since then had been Cleveland, in 1888, who faced a different opponent, with a different vice president, and still won the popular vote—but lost narrowly in the electoral college. With that exception, no sitting president had been defeated as his party’s nominee for a second term since Van Buren’s loss in 1840.

* * * * * *

The 1900 campaign was to be different from previous campaigns in several critical ways. It was the first time a vice presidential candidate took the lead in delivering speeches, for instance—Teddy Roosevelt gave nearly 700 speeches after his nomination, criss-crossing 24 states and racking up 20,000 train miles in an energetic, barnstorming fashion in just eight weeks.

As I wrote in my 2020 book, Forgotten Legacy: William McKinley, George Henry White, and the Struggle for Black Equality (LSU Press), the President announced he did not plan to campaign at all—with no appearances or speeches—“not even to conduct a ‘front-porch’ campaign as in 1896 … [but] ‘simply by doing his job.’ ”

McKinley addressing crowd in “front porch” campaign, 1896, Canton, Ohio. Courtesy Ohio Memory Collection

Still, his low-key, friendly bond with the common man remained one of his strongest assets; when he returned home to Canton from Washington in September 1900, out-of-town well-wishers greeted him with good-natured affection.

His response to one Pennsylvania fan’s question—“Major, what are you going to plan to do

with us the next four years?”—provided a humorously humble turn of phrase: “It is more

important just now to know what you are going to do with me the next four years.”

Not to be outdone, the admirer shouted back, “We are going to stand by you.”

So much for his silver-tongued opponent, nicknamed “the great commoner,” who gave almost as many speeches as did Teddy Roosevelt, but could not connect on the same level as his opponent. Bryan was able to raise less than a quarter of Republicans’ contributions that same year, while seeking, quixotically, to push campaign finance reform.

Bryan valiantly campaigned on an eclectic mix of issues, against imperialism, corruption, and corporate trusts, and for “The Issue—1900, Liberty, Justice, Humanity—Equal Rights to All, Special Privileges to None,” according to one popular poster.

William Jennings Bryan campaign poster, 1900. Courtesy Library of Congress

But his public identification with Southern Democrats and, by extension, with emerging “white supremacy” proponents, tended to weaken Bryan’s message. His base was worsened by the decline of the fast-fading Populist third party, which had endorsed him for president on a fusion ticket in 1896. By 1900, the once-fresh appeal of his 1896 “Cross of Gold” speech, as the nation’s most tireless defender of “free silver,” seemed to be slowly losing its luster.

McKinley still hoped to carry one or more Southern states in his rematch with Bryan, having carefully cultivated Democratic voters during his “Peace Jubilee” tour there in 1898. He had made strong showings in North Carolina and Virginia four years earlier, and was still extremely popular among African American voters, 80 percent of whom still resided in the South. But the truth was that disfranchisement had eroded more and more of the black Southern base, exacerbated by a “lily-white” movement within the Southern wing of his own party—and the President’s hope was more wishful thinking than practical strategy.

Under any circumstance, turnout—especially in Southern states—was notoriously difficult to predict.

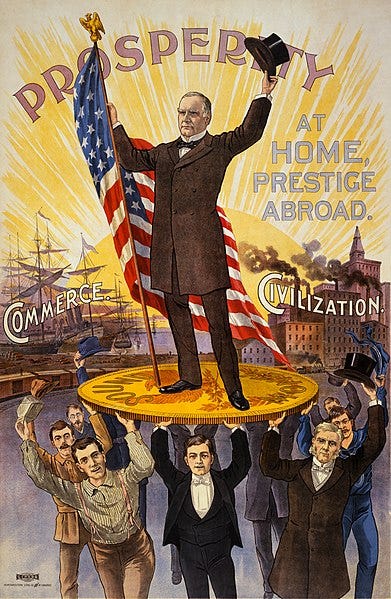

McKinley campaign poster, 1900. Courtesy Library of Congress

* * * * * *

“Prosperity at Home, Prestige Abroad. Commerce. Civilization.” was the message preached by McKinley, doffing his top hat and holding the flag while standing on a symbolic gold coin carried by men of all classes, on a very appealing campaign poster. Given the state of the economy—growing and healthy—prosperity seemed an attractive catch-phrase.

Meanwhile, Bryan relentlessly hammered what he saw as McKinley’s “imperialist” policy and its long-range implications. The raging civil war in the Philippines—America’s newly-acquired colonial province—was an issue of some uncertainty. If the Spanish-American war was long over, American soldiers were still fighting and dying in the hostilities there, as were Filipino rebels seeking nothing less than total independence.

And what was the precise future for Cuba and Puerto Rico—other former Spanish colonies much nearer home—and Guam, Samoa, and the newly-acquired U.S. territory of the Hawaiian Islands in the Pacific? Or did voters even care about such issues?

Without modern polling techniques, it was difficult to predict the mood of the voters with any scientific accuracy. In 1900, there was still no nationwide poll, only sporadic local “straw” polls in local taverns and other settings. The famous Literary Digest magazine polls, which began in 1916, enjoyed success for decades by using millions of completed questionnaires from its readers and others, correctly predicting the outcome of every presidential election until 1936.

But the Literary Digest poll and indeed, the magazine itself, disappeared after 1936, supplanted by George Gallup’s scientifically-selected sample of prospective voters, which predicted Franklin Roosevelt’s landslide reelection—the diametrically opposite result of that predicted by the Digest.

Before 1916, crowd size at campaign events was a rough additional measure of candidate popularity, combined with trends perceived in the most recent local and state elections. Newspapers on both sides of the political spectrum regularly sounded out political leaders of both parties for their readings of public opinion, which were clearly flavored by partisan desires and more likely to be reliable in local and congressional races than in national ones. It was a guessing game.

In the end, the economy prevailed as an issue in 1900. The McKinley-Roosevelt ticket was successful, actually building the Republican lead from 1896 to more than 800,000 popular votes, and defeating the Bryan-Stevenson ticket in the electoral college by an enlarged tally of 292 to 155. Bryan again carried the “Solid South,” this time adding Kentucky, but lost his home state of Nebraska and several of the Western states he had carried in 1896.

And what of the four candidates themselves? For William McKinley, it was his final election; after being sworn in for a second term, he announced in the summer of 1901 that he would not seek a third term. Later that year, McKinley was shot by an assassin in Buffalo, New York, and died eight days later of his injuries; he was 58 years old.

Vice President Theodore Roosevelt became president, at age 42, on McKinley’s death, and won reelection in 1904 by the largest majority ever received to date. He also ran unsuccessfully for a third term in 1912, but this time as an independent for his own Bull Moose Progressive Party. He died at age 60 in 1919.

William Jennings Bryan would sit out the 1904 election, but would go on to run a third time as the Democratic nominee in 1908—again with a new running mate, John W. Kern, his third. They were narrowly defeated by William Howard Taft and his running mate, James S. Sherman. Bryan would later serve as U.S. Secretary of State under Democratic President Woodrow Wilson in his first term. He died in 1925, at age 65.

In 1908, former Vice President Adlai Stevenson ran unsuccessfully for governor of Illinois, after which he retired from active politics. He died in 1914, at the age of 78. His grandson, also named Adlai Stevenson, was twice nominated for the presidency by the Democrats in 1952 and 1956, but lost both elections to Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Next time: Remembering the first “assistant president”