An obscure black hero saves a President, but cannot save himself

The brief, brave life and sad end of "Big Jim" Parker

He was a bona fide national hero in September 1901, vaulting briefly into the media spotlight by tackling the gunman who shot President William McKinley in Buffalo, saving the startled Chief Executive from a third and almost certainly instantly fatal shot. But almost as quickly as he appeared, “Big Jim” Parker was shunted aside when McKinley suddenly died of wounds, and was inexplicably forgotten by most Americans.

He is a perfect symbol of the kind of story one would expect to see retold in Black History Month, but instead is almost never remembered, much less reported these days—although his sensational story reeks of personal courage, with screaming headlines, darkened by racist undertones, and leads to a tragic end in an insane asylum just seven years later.

James Benjamin Parker (1857-1908), who intervened in William McKinley’s shooting in 1901.

I recounted details of the assassination in my 2020 book, Forgotten Legacy: William McKinley, George Henry White, and the Struggle for Black Equality (LSU Press), and saw Parker’s role as a fitting epitaph to McKinley’s often-overlooked record of hundreds of appointments for African Americans during his first term in office. Together with the activist black Republican congressman from North Carolina, George Henry White, the President had taken unprecedented steps to advance the prospects of the nation’s African Americans—in the face of growing white supremacy in the South and increasing apathy among members of his own party.

The 44-year-old “Big Jim”—sometimes called “Big Ben”—Parker, a towering, 6-foot-6 giant from Georgia, had come to Buffalo’s Pan American Exposition simply to hear the extremely popular McKinley speak. He had apparently been laid off the day before at the Plaza restaurant, and by some accounts, was waiting to be notified of yet another possible job as a waiter. He had missed the President’s major outdoor speech, delivered a day earlier to a crowd of perhaps 50,000, and assumed that he would make further remarks at his reception on September 6 in the Temple of Music. But he was mistaken; no speech was on the schedule, just a long receiving line.

Parker later said he almost left in disappointment, but decided at least to stay and shake McKinley’s hand. Awaiting his chance to greet the President, he stood just behind another, far shorter man with a bandaged hand. Without warning, Leon Czolgosz’s bandages erupted with smoking gunfire as McKinley reached out to shake his other hand. Two shots, at point-blank range, struck McKinley. The first shot was deflected by clothing; the second struck home in McKinley’s abdomen.

Czolgosz then raised his gun again for a third shot, one which would almost certainly have killed McKinley on the spot. And as the Buffalo Courier reported in its next edition, Parker took immediate action to prevent it: “the big Negro standing just back of him … struck the young man in the neck with one hand and with the other reached for the revolver.” One eyewitness told the Los Angeles Times reporter that Parker next “spun the man around like a top and … broke Czolgosz’s nose … split the assassin’s lip and knocked out several teeth.” He kicked the gun away, and assisted by as many as a dozen other men, wrestled Czolgosz to the floor.

Interviewed soon thereafter by the Buffalo Times, Parker himself selflessly played down his own role:

I did what every citizen of this country should have done. I am told that I broke his nose—

I wish it had been his neck. I am sorry I did not see him four seconds before. I don’t say that

I would have thrown myself before the bullets. But I do say that the life of the head of this

country is worth more than that of an ordinary citizen…

Yet despite the dozens of eyewitnesses who reported seeing Parker in the thick of the action, other bystanders—including, curiously, one of the two Secret Service agents at McKinley’s side—either ignored Parker’s presence completely or placed him much farther away from the President’s side. Competing newspaper accounts seemed to contradict each other, further confusing the issue. What was going on?

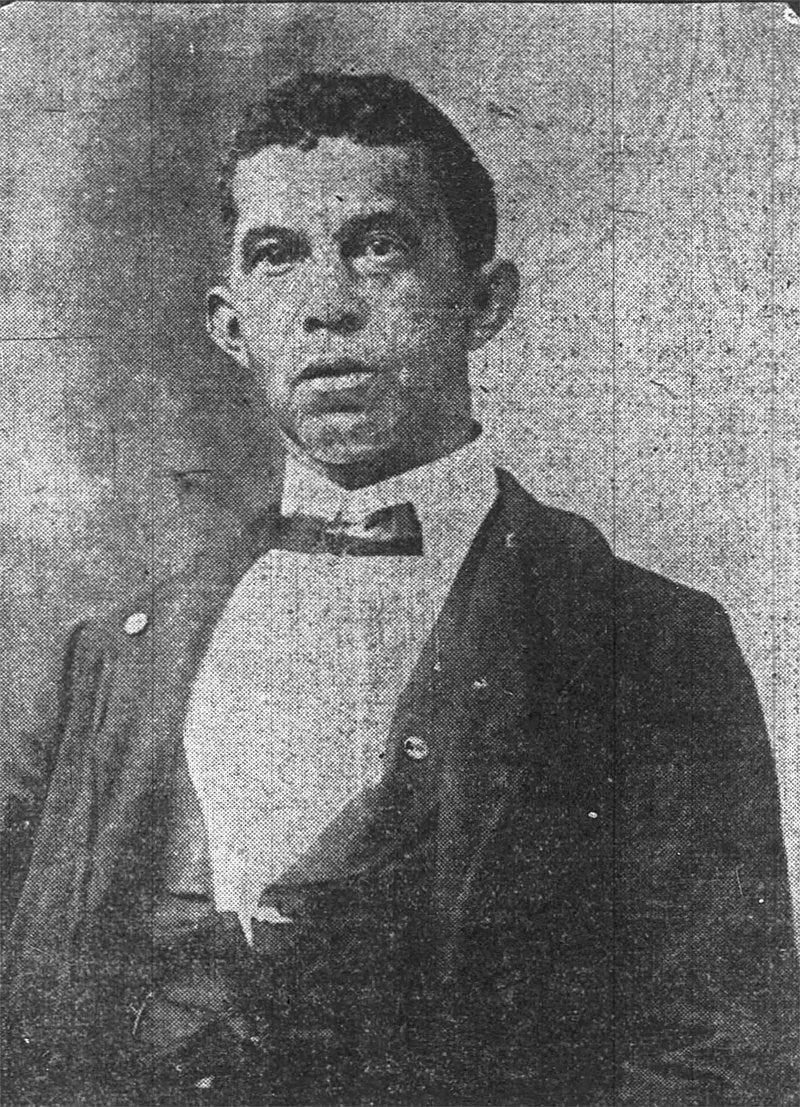

“Big Jim” Parker, as he appeared in 1901.

What happened over the next few days, and weeks, confounded the public. McKinley underwent surgery to remove the second bullet, and seemed for a time to be recovering. But the hidden damage was greater than surgeons were able to repair; modern antibiotics might still have saved him from the gangrene which soon set in, but were not yet available. The 57-year-old President died with little warning on September 14, sending the unprepared nation into a paroxysm of grief—and condemning Parker to increasingly rare mentions in the next round of newspaper stories.

Leon Czolgosz was expeditiously—and unceremoniously so—tried, convicted of murder, and executed six weeks after McKinley’s death. But James Parker was never called as a witness, his mere presence dismissed as irrelevant by Secret Service Agent George Foster, who did testify, recalling seeing “a colored man in the line, but it seems to me he was in front of [Czolgosz] … instead of behind him,” and denying Parker—or any black man—was involved in taking the assassin down.

Was it jealousy over not being able to protect the President himself? Foster had initially reported Parker’s involvement to his superiors, then changed his mind. Modern TV cameras or cellphones, of course, would have confirmed Parker’s presence immediately. As it was, only a photograph taken moments before the shooting, as he greeted well-wishers, exists to record the fateful receiving line; a rare film of McKinley reviewing troops at the Exposition a day earlier, captured by the Thomas A. Edison Film Company ( at https://www.loc.gov/item/00694343 ) and other earlier photographs, is also in the collection of the Library of Congress.

President William McKinley greeting the public at the Temple of Music, moments before he was shot.

Courtesy, Johnston Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

The somewhat fanciful wash drawing created in 1905 by T. Dart Wilson, a photograph of which is also housed in the Library of Congress, does show Parker alive in the artist’s imagination, at least, if no longer being discussed by newspaper writers, who had turned their adulation to newly-reelected President Theodore Roosevelt, who had succeeded McKinley in 1901.

Artist T. Dart Walker’s 1905 re-creation of McKinley’s assassination.

Courtesy, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C

But even as widespread public attention had begun fleeing from Parker’s humble grasp, public benefactors within his own race had embarked on a fund-raising campaign for him, most notably black Buffalonians and a more famous early civil rights leader, Mary Church Terrell, in Washington, D.C. On October 8, 1901, just a month after his heroic action, Parker actually met President Roosevelt at the White House, before addressing a large public gathering that night.

The Washington Evening Star, friendlier to African American coverage than most mainstream white newspapers, noted that Parker paid his respects to President Roosevelt in the company of a black newspaper editor, E. E. Cooper, and a well-known black politician from Baltimore, Hiram Cummings (“Parker to Lecture,” October 8, 1901). At his lecture, he was introduced to a large and appreciative crowd by an even more familiar figure, former Congressman George H. White (R-NC), who had stepped down from the House of Representatives only in March—and who had enjoyed a close political relationship with McKinley during their overlapping years in Washington.

Parker steadfastly refused to accept a speaker’s fee, having spurned lucrative commercial tour opportunities in the earliest days; the only monetary reward he did accept was forwarded to his aging mother in Atlanta. The success of Mrs. Terrell’s hastily-organized J.B. Parker Fund—to which contributors could offer small tributes in lieu of tickets—was never disclosed. Still, in Washington, he described the events of September 6 in faithful detail, and offered his own thoughts during and after the event.

“I don’t why I wasn’t summoned to the trial,” he declared toward the end of his speech. One female listener shouted her opinion: “‘cause you’re black, dat’s de reason” (“Parker Tells His Story,” Washington Colored American, October 12, 1901). Prosecutor Thomas Penny had taken his statement, Parker explained: “It looks mighty funny, that’s all. Because I was a waiter, Mr. Penny thought I had no sense.”

That answer—invoking public officials’ racism—certainly resonated among the wider audience, many of whom still mourned the death of a favored race benefactor—and who warily distrusted Roosevelt, his successor, known for his less than charitable public comments about the valor of black soldiers at the famous battle of San Juan Hill.

* * * * * *

Parker continued his speaking engagements, but for all practical purposes, gradually disappeared from the public eye in the months and years after. Whether he returned to work at any of his previous occupations—sheriff’s constable, magazine salesman, waiter, or as a Post Office laborer (Chicago)—cannot be determined. He does appear to have prospered briefly, until his health apparently began to fail—some later attributed it to a drinking problem and dissolute lifestyle, while unconfirmed hints suggest that he may have contracted a deadly disease, perhaps tuberculosis or even syphilis.

In early 1906, however, he suddenly reappeared, seeking assistance from the widow of President McKinley in a desperate letter penned on stationery of a Washington, D.C., genito-urinary specialist, Dr. Francis Hagner, parts of which are excerpted below:

Kind Madam, I wish to ask a favor of you. I have been sick in the hospital for some time

and am sick yet. … A word from you to Mr. [George] Cortelyou is all I need. I don’t ask for

a clerkship but anything he will give me … driving a wagon to a place in the U. S. capital. If

you will so this for me in remembrance of y our dear husband I will always pray to our

heavenly father to spare your life and have mercy on you…

Much moved by the personal appeal, despite her own increasing frailty, Ida McKinley immediately forwarded the letter to Cortelyou, once her husband’s personal secretary, former Secretary of Commerce and Labor in Roosevelt’s first term, now the U.S. Postmaster General. According to author Carl Sferazza Anthony (Ida McKinley: The Turn-of-the-Century First Lady Through War, Assassination, and Secret Disability), Cortelyou may have found employment for Parker as a messenger, but if so, it was too little, too late.

Ida Saxton McKinley (1847-1907), U.S. First Lady, 1897-1901.

Courtesy Johnston Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

As noted in the epilogue of my book,

… within a year, Parker was destitute on the resort streets of Atlantic City, New Jersey,

after being a performer for various hotels and saloons. An emaciated panhandler there in

early 1907, he was arrested for vagrancy and judged by a benevolent judge to be unable

to care for himself; rather than jail him, the judge ordered him confined to an asylum

for the insane in West Philadelphia.

Parker’s health and huge frame had been ravaged by disease and apparent alcoholism,

according to one friendly witness: “Prosperity and too much glory proved the undoing

of Jim.”

Parker’s alarming fate was duly chronicled by the New York Times (“McKinley Protector Mad?”, March 23, 1907) and the Washington Post (“Prosperity His Undoing,” March 23, 1907). Two months later, Mrs. McKinley herself passed away, perhaps unaware of Parker’s confinement and rapid decline. The reports were followed a year later by the Washington Post’s account of his recent death and grisly dissection (“Dissect Body of Hero: Medical Students at Work on McKinley’s Defender,” March 27, 1908) at the Jefferson Medical College.

To me, at least, the dissection was a “near-ghoulish denouement to the fate of the assassin he had once tackled.” As well reported nearly seven years earlier, Leon Czolgosz’s body had been dissolved in acid after his electrocution in October 1901. Parker’s dissection, however scientifically useful, was hardly a hero’s burial. Ironically, Parker died within blocks of the new home of onetime introducer and former congressman George Henry White, now a Philadelphia banker and land developer.

More than a century later, Parker has begun to receive renewed study by a growing group of historians and authors, one more hero rescued from the dustbin of history.

Next time: And now for something completely different, Part 1 …