African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 1: Becoming party delegates to the national Republican convention, 1868

It was a unique moment in American political history. As the nation’s Republicans gathered in Chicago at Crosby’s Opera House in May 1868 to nominate Ulysses S. Grant for president, the 650 voting delegates—plus an unspecified number of alternates—displayed a small but unmistakable difference from their predecessors.

For the first time, accredited African American delegates from seven Southern states were among those voting for their party’s presidential nominee. At least one future member of Congress—South Carolina’s Robert Smalls, who served all or part of five terms in the U.S. House in the 1870s and 1880s—was among them, joining as many as nine future members of their respective state legislatures.

As I continue my long-running research for a future book on the subject chronicling black Republican delegates between 1868 and 1920, I thought readers might enjoy a preview of excerpts from the draft manuscript.

So far, my preliminary results show as many as 29 African American delegates and alternate delegates were named between January and May 1868, at least, to attend that year’s GOP convention. They included 12 voting delegates from at least seven Southern states—Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia—and 12 alternate delegates named from four states: North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas. In addition, four African Americans from Maryland—a competing slate of one delegate and three alternates elected by a Radical rump convention in Baltimore—were seated out of courtesy in a compromise deal, but not allowed to vote.

It was, of course, the first party convention held since the end of the Civil War—and the first since the adoption of the 14th Amendment to the US. Constitution, mandating citizenship for African Americans. Although not all of the former Confederate states had yet amended their state constitutions to allow black men to vote, most were well on the way to doing so—primarily because they were required to do so in order to gain readmission to Congress. Under the leadership of their currently-dominant Republican parties, Tennessee had approved the 14th amendment in 1866 and allowed blacks to vote since 1867, while North Carolina had already held its first statewide elections under its brand-new Reconstruction constitution, approved in January, and that state’s first two dozen black legislators were due to take office in July.

North Carolina was among seven states who expected to be readmitted to Congress during the summer of 1868; the others were Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and South Carolina, all of whom approved the 14th Amendment between April and July of 1868, when the Amendment was declared by Congress to be in effect. [Virginia (1869), Mississippi (1870), and Texas (1870) formally ratified the 14th Amendment only after it entered into effect; as a result, voters there were not allowed to participate in the November presidential election.]

Delegates from all 11 former Confederate states were certified to the GOP convention in May, however. And all but three of those states sent at least one black delegate or alternate to Chicago; the rest—Alabama, Florida, and Georgia—would begin sending black delegates in 1872.

In all, 29 African Americans were chosen as state representatives to the Chicago convention. It is not clear how many of them actually attended the convention; one alternate delegate from Tennessee died weeks before the convention, trimming the possible total to 28. Two reasonably authoritative journalistic accounts—published in the Washington Evening Star and New York Times—each mentioned “nineteen colored delegates,” but carried no names.

The Official Proceedings of the Republican National Convention 1868 do not specify the race of any delegates or alternates in the official list, making the process of identifying African Americans from other sources cumbersome and tricky. To make matters worse, actual state delegate lists in the Proceedings are often incomplete, not always listing alternates by name. (The GOP appears to have paid traveling expenses only for its voting delegates; alternate delegates were encouraged to attend, but likely at their own expense.)

And just how active these delegates were in the convention is also not clear. The day-to-day minutes of the convention mention only two specific names out of the 28 on my composite list, both well-known beforehand—delegate Henry E. Hayne of South Carolina [future Secretary of State], named to the Committee on Credentials, and alternate delegate James H. Harris of North Carolina, a future legislator and congressional candidate, who was proposed as a speaker on the convention’s second day—by a delegate from the District of Columbia—but not inside the hall to come forward during a brief window of opportunity.

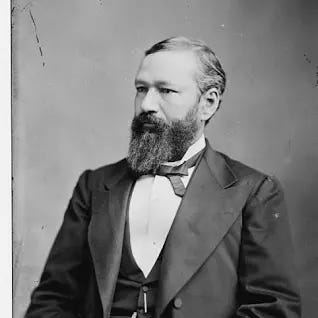

Henry E. Hayne (1840-1898?), SC voting delegate in 1868. Public domain photo

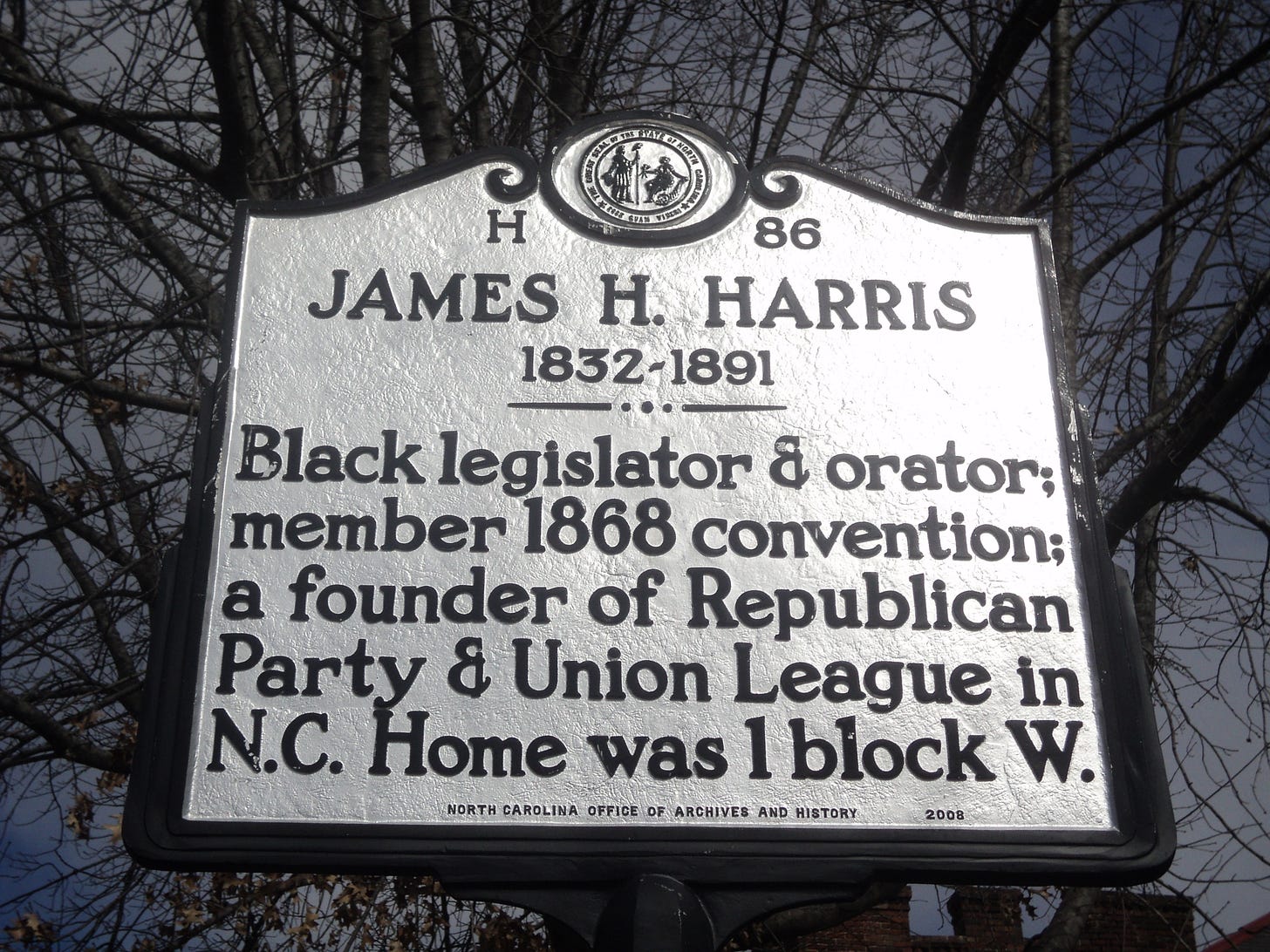

Raleigh historical marker commemorating NC alternate convention delegate James H. Harris in 1868. Public domain photo

But the New York Times and other newspapers give other credible hints. The Times, for instance, published a lengthy list of most state delegates—covering all former Confederate states except Texas— the day before the convention opened on May 20. Among them were names of 10 “colored” delegates. They included voting delegates from Arkansas (William H. Grey), Mississippi (James Lynch, Secretary of State), and North Carolina (recently elected state legislator John Sinclair Leary)—and three “colored” alternates, all from North Carolina: future congressman James Edward O’Hara, recently-elected legislator James H. Harris, and future legislator John R. Page. [The Times also names the entire insurgent slate from Maryland, including four “colored” members, challenging the state’s official slate.]

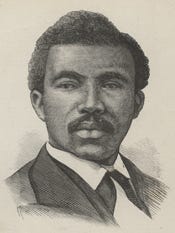

William H. Grey (1829-1888), Arkansas voting delegate in 1868. Public domain photo

John Sinclair Leary (1845-1904), North Carolina voting delegate in 1868. Public domain photo

James D. Lynch (1838-1872), Mississippi voting delegate in 1868. Public domain photo

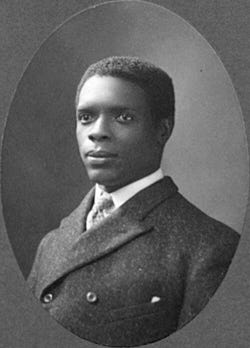

Future NC congressman James E. O’Hara (1844-1905), alternate delegate in 1868. Public domain photo

John R. Page (1840-1900), North Carolina alternate delegate in 1868. Public domain photo

Newspaper accounts of the earlier party nominating conventions in Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia are also useful resources. Within the next decade or so, at least five men on those lists would gain national fame as African American politicians of national renown: Louisiana’s delegate, P. B. S. Pinchback, by being elected his state’s lieutenant governor, and serving briefly as governor—and four others by being elected to Congress, including one voting delegate (Robert Smalls) and three alternates: O’Hara, and South Carolina’s Robert Brown Elliott and Joseph H. Rainey.

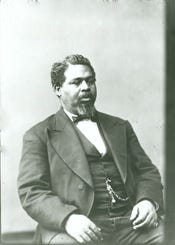

Pinckney B. S. Pinchback (1837-1921), Louisiana voting delegate in 1868. Public domain photo

Robert Brown Elliott (1842-1884), South Carolina alternate delegate in 1868. Public domain photo

Robert Smalls (1839-1915), South Carolina voting delegate in 1868. Public domain photo

Joseph Hayne Rainey (1832-1887), South Car9lina alternate delegate in 1868. Public domain photo

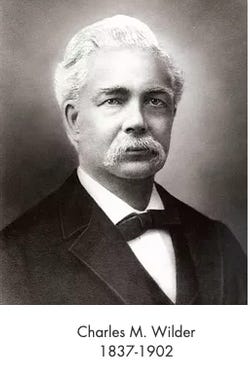

Others had already become more familiar to state residents by serving as delegates to their state’s recent constitutional conventions, mandated by Congress before being allowed to rejoin the Union—and by subsequently winning election to one or both houses of their legislatures, including Harris, Page, and at least eight more. One of those legislators, South Carolina delegate Charles M. Wilder, a physician and legislator, would also soon become one of the nation’s longest-serving black postmasters, holding that post in his state’s capital, Columbia, for a longstanding record of 16 consecutive years (1869-1885).

Dr. Charles McDuffie Wilder, South Carolina voting delegate in 1868. Public domain photo

But identifying any single delegate or alternate—except for Harris and Hayne—as being physically on the floor during the convention is nearly impossible. Among the 28 possible attendees I studied, only five voting delegates and nine alternates—a total of 14—are actually even named on their states’ delegate lists in the printed version of the Proceedings. The state lists—especially from the Southern states, who had never attended Republican conventions before—were often submitted in incomplete status, with last-minute substitutions or additions made in Chicago.

The longer New York Times list of delegates—obviously obtained from officials at the actual convention—contains 19 of the 28 possible names, although only 10 are identified as “colored.” [The Times list also omits delegates from Florida and Texas, along with those from the District of Columbia and U.S. territories; no delegates or alternates from those states or territories were black in 1868.]

Next time: Part 2: Chicago sets the standard for the future of GOP conventions