African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 7: Seeking to renominate affectionate favorite Ulysses Grant in 1880

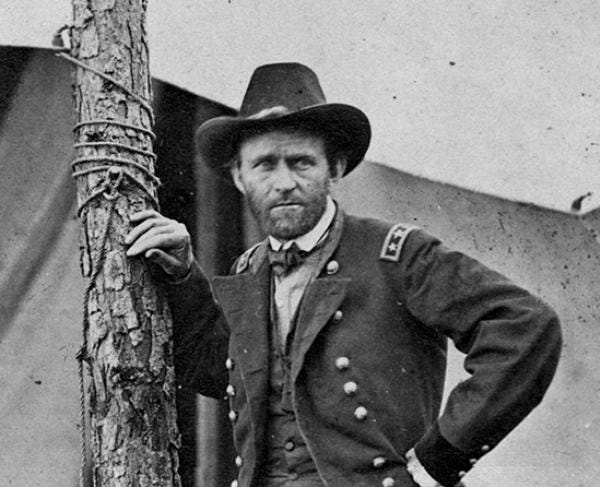

When the nation’s Republicans gathered in Chicago in June 1880 to choose a possible successor to outgoing President Rutherford B. Hayes, the sentimental favorite was former two-term chief executive Ulysses S. Grant, who had declined to seek a third term in 1876.

Some observers were already predicting an outright victory on the first ballot for the popular ex-President, and it is clear that he enjoyed early strong support over his major opponents: former U.S. House speaker James G. Blaine and former U.S. Senator John Sherman, now serving as Secretary of the Treasury.

Grant was clearly the favored choice of a majority of the convention’s 65 identifiably black delegates, almost all of them from the 11 former Confederate states, who formed almost 9 percent of the convention’s 756 voters. Black delegates in smaller numbers had unanimously endorsed Grant’s previous nominations in 1868 and 1872, and given the opportunity, would almost certainly have chosen him for a third term in 1876.

Based on my continuing research for a proposed book on political participation by African Americans in Republican conventions between 1868 and 1920, I have previously described the settings of those conventions in Chicago in 1868, when about a dozen black delegates were able to vote; Philadelphia in 1872 (at least 55 voting delegates); and Cincinnati in 1876 (at least 55 delegates).

By the time of the first ballot, Grant’s support was still strong, winning 304 votes of the 379 necessary for the nomination. But Blaine was close behind, with 284 votes, with Sherman drawing third place at just 98 votes.

Former president Ulysses S. Grant sought a third term in 880. Photo courtesy American Battlefield Trust

Analyzing the precise level of Grant’s support among black delegates in 1880 is a tricky process. Nowhere in the public proceedings is there a breakdown by vote by race of delegate. But preliminary indications from other sources are that Grant probably drew at least half of their votes, among the 128 votes by Southern delegates given him on the first ballot—and a fair number would continue to vote for him until the very last ballot, the 36th, days later.

Here is a provisional breakdown of the first ballot’s outcome:

— Five Southern states—Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, South Carolina, and Virginia (30 black delegates in total)— went unanimously or almost unanimously (80 percent) for Grant, giving him 67 of their combined 78 votes.

—Two Southern states — Tennessee and Texas (4 black delegates)—went heavily for Grant, giving him 27 of their combined 40 votes.

— Five Southern states —Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, and North Carolina (30 black delegates)—split their votes, giving Grant 38 of their combined 90 votes.

— The District of Columbia split its two votes (1 black delegate) between Grant and Blaine.

My calculations shows that at least 21 of the 65 black delegates—from Arkansas (unanimous), Florida (unanimous), and South Carolina (13 of 14)—certainly voted for Grant. At least half of Alabama’s eight black delegates—even if all of the four non-Grant voters were black—followed suit, bringing the total to 25. Another six black delegates in Maryland (1), Mississippi (3), and Tennessee (2) probably did the same—based on their 36th ballot votes for Grant, the only ones recorded by name in polling of the delegations. This brings the likely minimum total to at least 31 for Grant at the outset.

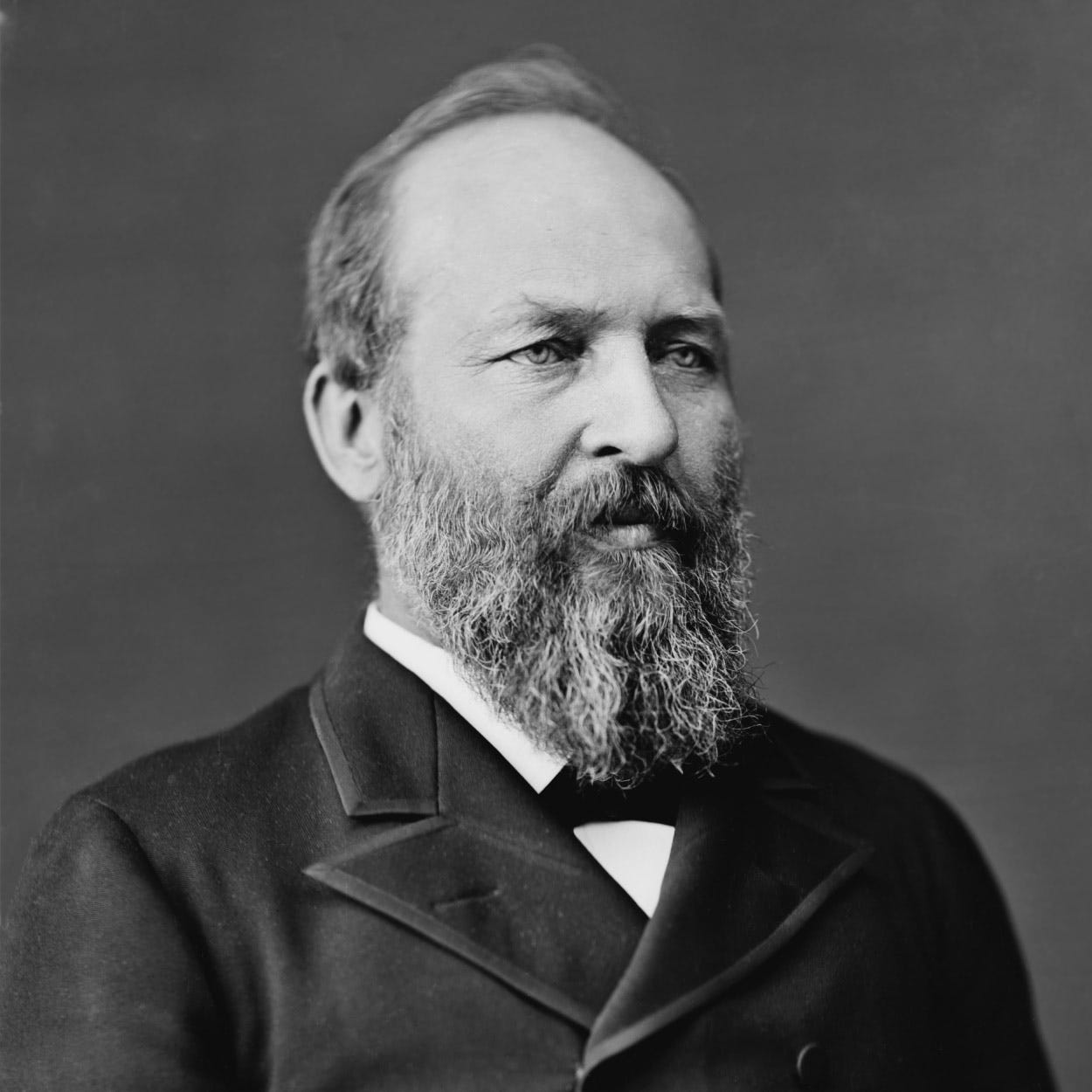

Treasury Secretary John Sherman, 1880 candidate for GOP nomination. Public domain photo

By the 36th ballot, of course, sentiment had begun to shift toward the inevitable selection of a compromise candidate. Grant’s total had been steady, fluctuating only slightly above its original 308—reaching a high of 313 on the 35th ballot—and the backstage negotiations which suddenly elevated James Garfield to success on ballot 36 had attracted at least some of the more receptive black delegates who had long supported Grant.

Republican President James A. Garfield, nominated on the 36th ballot in 1880. Public domain photo

Among them were such rising stars as Mississippi congressman John Roy Lynch, a 33-year-old alternate delegate in 1880 who gives an extraordinarily lucid account of Garfield’s emergence in his autobiography (Reminiscences of an Active Life, published nearly a century later):

… After a number of fruitless ballots, it became apparent that neither of the three leading candidates could possibly be nominated. Very few, if any, of the Sherman men would go to Blaine, while the Blaine men [refused] to go either to Grant or Sherman … When Garfield’s name was suggested as a compromise candidate, he was found to be acceptable to both the Blaine and the Sherman men and to some of the Grant men who had abandoned all hope of Grant’s nomination. The result was that Garfield was finally made the unanimous choice …

Lynch, though simply an alternate, was present on the floor for the Garfield victory—and would actually be called forth to vote—in the absence of a delegate and his own alternate— on that critical 36th ballot. He would, in fact, cast his vote for Garfield, admitting in his autobiography that he had always preferred Grant. And although he was about to be defeated for reelection to a third term in Congress, he would continue to have a long career in politics, serving part of one more term before his second and final defeat in 1882.

Rep. John Roy Lynch (1847-1939), alternate delegate at 1880 convention. Public domain photo

Lynch would, however, continue to serve as a Mississippi delegate to four of the next five Republican conventions, as well as hold important patronage appointments. Despite his relative youth, he had already served as Speaker of the Mississippi House of Representatives, and was a protege of both U.S. Senator Blanche K. Bruce and then-Congressman and future President, William McKinley, who privately favored him for election as temporary chairman of the 1884 convention four years hence—the first African American ever honored in that way.

Bruce, now completing his term as the nation’s second black U.S. Senator, presided briefly over the 1880 convention, as one of the state vice presidents chosen by the convention. Both Bruce and Lynch had first attended the 1872 convention as Mississippi delegates; Bruce would also attend the conventions in 1884 and 1888, before moving to Washington permanently in the 1890s.

U.S. Senator Blanche K. Bruce (1841-1898), a GOP delegate in 1880. Public domain photo

But Bruce’s signal honor at the 1880 convention was certainly his nomination for the vice presidency, becoming the first first black man ever so nominated. On behalf of the Mississippi delegation, spokesman John Lynch offered his colleague’s name, as follows:

It was a purely symbolic effort, as Lynch himself acknowledged; the Mississippi delegation had already committed the bulk of its votes to supporting consensus candidate Chester A. Arthur of New York, who was overwhelmingly nominated on the impending vice-presidential ballot.

In all, Bruce received just eight votes of the 756 cast, but even so, placed fifth among the nine contenders—even outpacing his white Mississippi colleague and fellow delegate, James Alcorn, by receiving four votes from Louisiana, two from Indiana, and one each from Michigan and Wisconsin.

Next time: Chicago becomes the default setting for the Republican convention