African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 16: Getting down to business in Saint Louis in 1896

Last time, I sketched the setting of Missouri’s largest city and the record number of black delegates—at least 75—selected to attend the 1896 Republican convention, mostly new faces in a sort of generational change for the party, seeking to regain control of the White House after enduring a second four-year term for Democrat Grover Cleveland.

Four years out of favor nationally had again effectively deprived the party’s African American wing of its traditional right to claim postmasterships and other patronage positions. For example, Cleveland had appointed fewer than a dozen new black postmasters—mainly to black Democrats in small communities in Oklahoma and Kansas—during his second term, compared to around 100 appointed by President Benjamin Harrison between 1889 and 1893.

With just one black Congressman—South Carolina’s George Washington Murray—and little political clout beyond their state parties in a handful of Southern states, black leaders struggled to regroup behind the consensus favorite, former Ohio governor William McKinley, in hopes of regaining past glories.

McKinley’s trusted ally and campaign manager, Marcus A. Hanna, had begun introducing him to influential black leaders more than a year earlier at his winter home in Thomasville, Georgia, followed by a remarkable trip east to Florida, where McKinley entertained scores of black party leaders in his large hotel suite. Since then, Hanna had quietly begun extending promises of significant appointments in a new McKinley administration in exchange for promises of support on the first—and with luck, final—ballot.

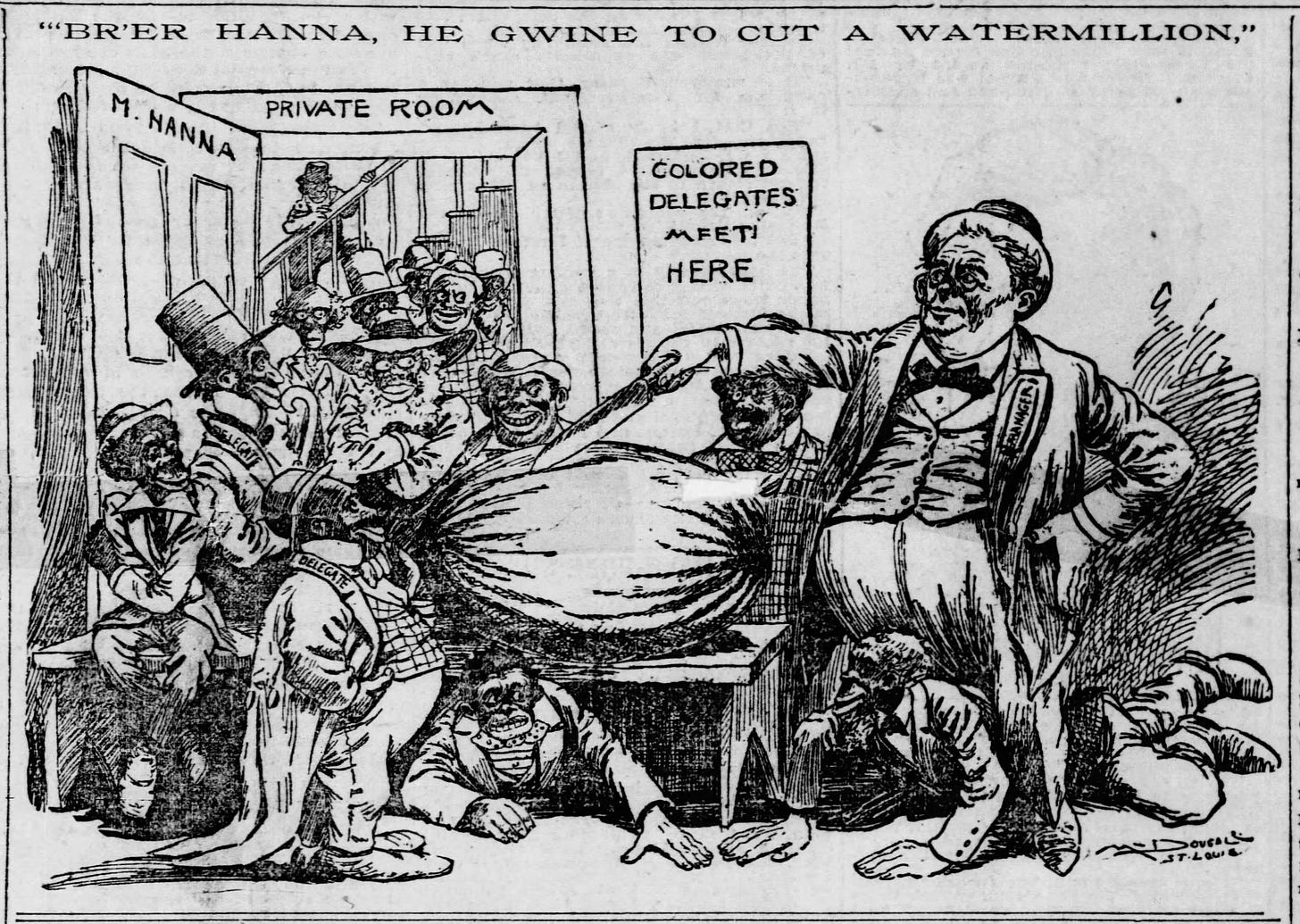

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch ridiculed the Hanna strategy with a racist cartoon on its front page (“Bre’r Hanna, He Gwine to Cut a Watermillion,” June 15, 1896) the day before the convention officially opened. An article just below that cartoon trumpeted a contradictory point of view held by Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, who met with black delegates from Florida and South Carolina and believed “the colored Southern delegates have been badly treated by the McKinley managers. T hey were promised very great consideration and received none” (“Sambo for Fat Tom,” June 15).

New York alternate delegate Caleb Simms, one of a handful of Northern blacks at the convention and reportedly a “prominent [Thomas] Platt man … instructed alternate for Morton,” was described by the Post-Dispatch as “one of the leaders in the movement of the colored men toward [Thomas] Reed,” one of McKinley’s opponents. But his efforts, however successful, were not significant enough to turn the tide.

Although a handful of black delegates were apparently not happy with either McKinley or Hanna, and some, especially in North Carolina, were unenthusiastic about the “gold bug” platform plank, most Southern blacks followed the Hanna lead for McKinley on the first ballot and on the platform. McKinley amassed 661 votes on the first ballot, out of 924 available; of his total, 196 votes—nearly a third— came from the Southern states, against fewer than two dozen tallied there for Reed and a scattering for other candidates.

A handful of black delegates in six states—Alabama (2), Florida (1), Georgia (3), Mississippi (1), and Texas (2), who were identified by name during polling required by technical challenges—favored Reed. Eight of the Southern delegations—Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia—were unanimous or nearly so for McKinley.

But the balloting for vice president revealed a sharp divergence from the presidential nominee’s choice for a running mate. Southerners proved far less enthusiastic, instead heavily favoring Tennessee’s Henry Clay Evans over eventual winner Garret A. Hobart, by 124 votes to just 68. In that ballot, North Carolina provided just one of its 22 votes for Hobart, South Carolina just three of 18, and Georgia just five of 26; Tennessee (24) was unanimous for Evans, its favorite son, while Virginia gave its 24 votes to another favorite son, Rep. James Walker, the state’s only Republican congressman.

Campaign button for the 1896 presidential ticket. Courtesy Henry Ford Museum

black delegates—Monroe Morton of Georgia and Edmund Deas of South Carolina—were then selected to serve on the notification committee for McKinley. Meanwhile, just one Southern black delegate—North Carolina’s Jonathan Hannon, a former postmaster, who had favored McKinley over Harrison at the 1892 convention, and was perhaps the single vote received by Hobart in that state’s 1896 delegation—was chosen to serve on Hobart’s notification committee.

* * * * * *

Overall, the influence of black delegates at the Tepublican convention seemed to be declining since previous conventions, reflecting what seemed to be a regional trend. Norris Wright Cuney, the longtime Texas leader, had been replaced that year by a white party leader, ending an era there, and was not even present at the 1896 convention.

Neither John Lynch nor Blanche Bruce, longtime leaders in Mississippi and still active nationally, made that year’s cut—due in part to continuing machinations by national committeeman James Hill—nor did John Mercer Langston, the former congressman from Virginia, who was now retired from politics. Only Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina seemed to have retained strong black leadership in their state’s parties

The platform planks favored by black delegates on two important subjects—lynching and the Blair education bill—were far weaker than the caucus had hoped for, and no major addresses were delivered by either delegates or distinguished black visitors in 1896, a stark comparison to most recent conventions. The absence of perennial visitor Frederick Douglass, who had died a year earlier, was just one tangible reminder of the gradually declining political fortunes of the race in the South, beset by disenfranchisement movements and marred by increasing violence.

Blacks also received somewhat fewer committee assignments during the 1896 convention than in previous years, with only three delegates named to the prestigious Rules committee—Hugh Carson of Alabama, Edward Richardson of Georgia, and George Henry White of North Carolina—and just two to the committee on permanent organizations: Perry Carson (District of Columbia) and Wesley Crayon (Mississippi).

Three more black delegates were named to the resolutions committee—Alabama’s Herschel Cashin, Mississippi’s Edward Lampton, and Florida’s Isaac Purcell—but just one, South Carolina’s John Fordham, was chosen for the important credentials committee.

Two black members were named to the Republican National Committee: newcomer Judson W. Lyons of Georgia and James Hill of Mississippi, named to his second term.

Swimming against the tide, as it were, was Perry Carson of Washington, D.C., a longtime veteran delegate who had attended every convention since 1884 and served on the Republican National committee for the past two decades, from which he was soon to retire. Apparently determined to make his presence known in Saint Louis, Carson had even waged a Don Quixote-like campaign for the presidency. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Carson, “the negro king of the capital,” was determined to claim the nomination [“Wants First Place or None,” June 14, 1896] despite the heavy odds against him.

Perry H. Carson, District of Columbia delegate in 1896. Public domain engraving

“If I can secure the nomination I am sure to win. No matter who the Democrats nominate, I will be elected,” he said, “because the Republicans of this country are loyal enough to their party, I think, to vote for the regular nominee of their party, black or white.” Present as a nominal supporter of longtime Iowa Senator William B. Allison, he disavowed any interest in being vice president under Allison or anyone else, especially McKinley: “I never was a McKinley man.”

While barely recognized outside Washington, D.C., he was certainly physically impressive, according to the newspaper article: “Col. Carson stands 6 feet three, and seven of him would weigh a little more than a ton … He wears a moustache and a goatee and a little dab of white whiskers on either side of his face. He is about 50 years of age and has a voice like a foghorn.” A former deputy U.S. marshal, he had recently held two mid-level appointments in the Washington city government.

Whimsical or not, Carson’s presidential boomlet soon ended. He had but one brief, somewhat baffling mention in the convention’s official proceedings, during a vote on credentials:

When the District of Columbia was called, Perry H. Carson, a delegate from the District of Columbia was endeavoring to get the eye of the Chair. When finally recognized, he asked:

"I want to know about the vote ‘yea’ and the vote ‘nay’ — what it means." (Laughter and cheers.)

The CHAIR. The Convention is now voting on a motion to lay the substitute offered by the Senator from Colorado on the table. A "yea" vote is to lay it on the table.

Mr. CARSON. I only wanted to know whether our delegation voted, right or not and I find it did vote right. (Laughter and cheers.)

It would mark his final appearance as a D.C. delegate at the party’s convention. in 1900, he would be replaced by Washington Bee publisher W. Calvin Chase.

* * * * * * *

More than 40 black delegates from the 1896 convention would be chosen to represent their respective states again at Philadelphia in 1900, when William McKinley would be nominated for a second term as President. Among them would be Rep. George Henry White of North Carolina, completing his second term in the U.S. House.

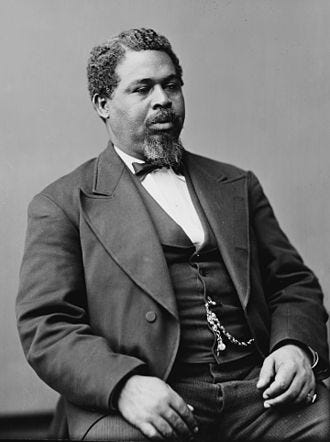

Those enticing promises made by Mark Hanna at Saint Louis in 1896 would not be forgotten. Many of the 1896 delegates, in fact, would benefit from their presence by being appointed to federal patronage jobs during the first McKinley administration, including Judson W. Lyons of Georgia, who would succeed the late Blanche Bruce as Register of the Treasury in April 1898; former congressman Robert Smalls of South Carolina, to be reappointed as Collector of the Port of Beaufort in 1897; and Thomas C. Walker, appointed as customs collector at Tappahannock, Virginia.

Judson W. Lyons, 1896 Georgia delegate and future Treasury Register. Public domain photo

Robert Smalls, 1896 S.C. delegate, soon reappointed as Collector of Port of Beaufort. Public domain photo

Thomas Walker, 1896 Virginia delegate, soon to be customs collector at Tappahannock, Virginia. Public domain photo

A smaller number of the 1896 delegates would also become postmasters, including Monroe B. Morton, appointed postmaster of Athens, Georgia, in 1897, and longtime Florence, South Carolina, postmaster, reappointed by McKinley to that post in 1899. During his first term, McKinley would indeed appoint the most black postmasters of any president to date—more than 100, exceeding Harrison’s total between 1889 and 1893.

Next time: Reconvening in Philadelphia in 1900, to renominate William McKinley