African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 17: End of an era, helping renominate McKinley in 1900

This week, I examine the critical 1900 convention of the Republican party, which in many ways, was the end of an era for Republicans, white and black. As usual, this blog entry is based on my continuing research into African American political participation in the Republican national conventions from 1868 to 1904—the subject of my planned book, continuing my 25-year odyssey into shadowy corners of U.S. history during the late nineteenth century.

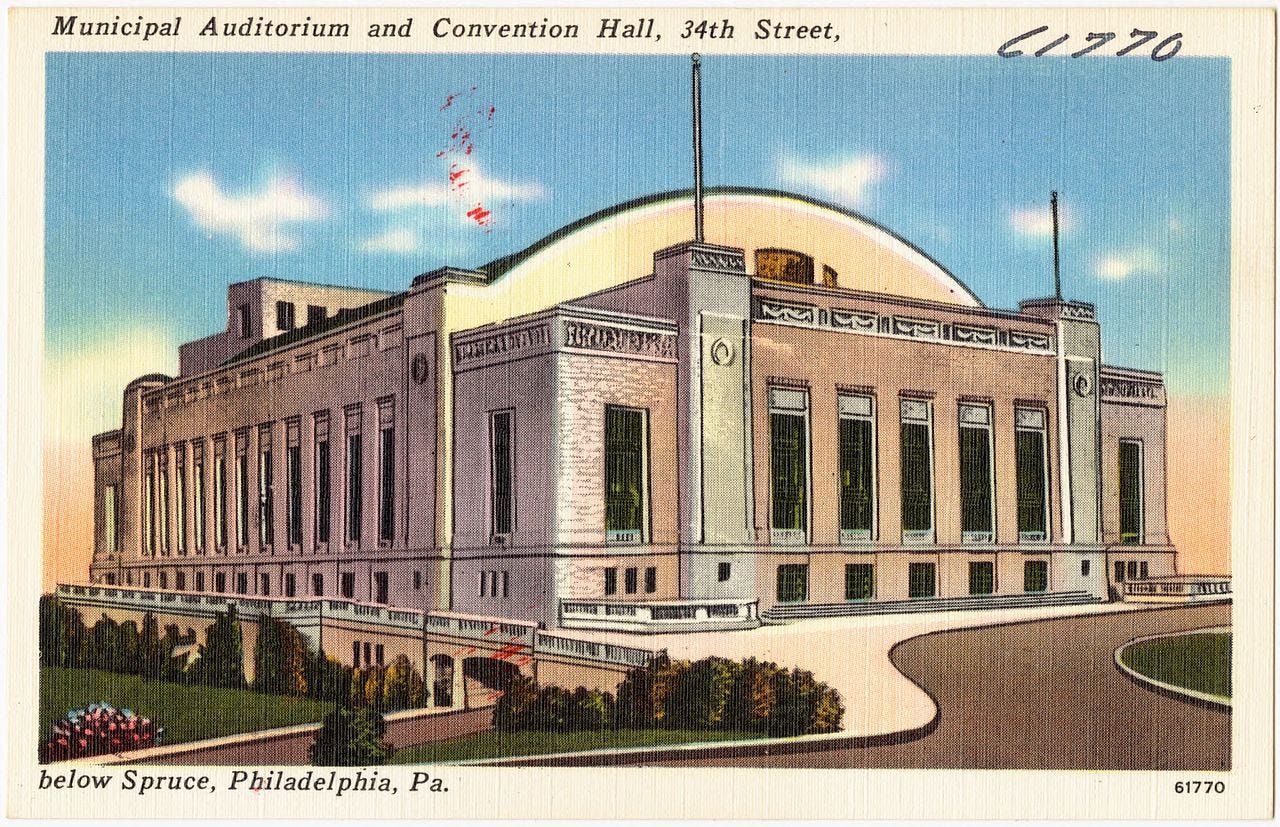

It was the last nominating convention the party would hold in the nineteenth century—the twentieth century technically did not begin until January 1, 1901—and the last time such a convention would be held in an Eastern state for four decades. (Philadelphia, the site in 1856 and 1872, would also host the next East Coast meeting in 1940; after 1900, Republicans returned to Chicago from 1904 through 1920 and again in 1932, followed by Cleveland and Kansas City.)

But for black delegates, the 1900 convention would mark an even more significant milestone: it was the last gathering at which any black political giant of the Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction eras would play a major role. A new generation of younger black leaders was preparing to assume command, under rapidly changing circumstances, a process exacerbated by the absence of black representatives from Congress. Disfranchisement in most Southern states and major deaths had already played roles in the decline of black political influence—both former Senator Blanche Bruce and former Congressman John Mercer Langston had died since the 1896 convention, along with influential longtime Texas leader Norris W. Cuney, among others.

Tellingly, the 1900 gathering would mark the last convention at which a sitting black Congressman—North Carolina’s George Henry White—would be a voting delegate for at least three decades. And while White was joined by at least three of his predecessors as delegates in Philadelphia, all would find their roles diminished by changed circumstances, including the emergence of a “lily-white” Southern wing of the once proudly-biracial party.

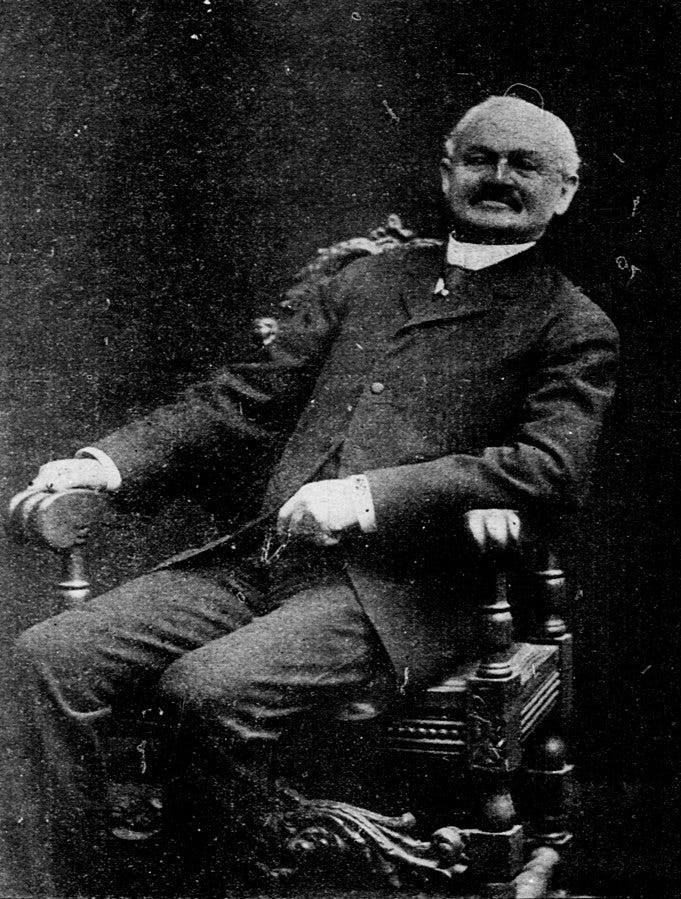

Rep. George Henry White, North Carolina delegate in 1900. Public domain photo

Quietly underscoring their waning influence, the number of black delegates in Philadelphia was also markedly lower than in recent years, with just 53 black delegates identified so far in my ongoing research, representing 12 states and the District of Columbia. It was, in fact, the smallest number since the first convention any of them had attended in 1868 (when just 12 voting delegates appeared), and more in line with the number selected in the Reconstruction-era conventions of 1872 (56) and 1876 (55).

Conversely, the number of black alternate delegates chosen in 1900—at least 71, from 19 states—was the second highest total in party history, down only slightly from the high of 74 black alternates identified in 1892. If the number of alternates in attendance at most conventions only be documented anecdotally—generally in newspaper reports which mention specific names, because alternates are rarely called upon to address a convention, and named only if they actually vote, when a challenge occurs—there is one unique supporting document from the 1900 convention which names and depicts at least 34 black alternates, along with nearly 700 other delegates and alternates.

An art souvenir of the Republican national convention, held at Philadelphia, June 19-22, 1900 was a pictorial memoir of the convention, compiled and published months later by a Philadelphia publishing firm, Gatchel & Manning Engravers & Illustrators. A speculative venture, it contained copper engravings of “those who, coming from ocean to ocean and from the lakes to the Gulf, assembled in our loyal city in June last to name a ticket in the present campaign, and to have executed therefrom 700 half-tone copper plates, have involved an expense and labor, not to say persistence, that has been truly great.”

Cover page of the Art Souvenir book published in October 1900. Courtesy Library of Congress

The black alternate delegates—representing nearly half of those who were actually named to attend— were depicted in the nearly 400-page book, along with at least 28 of the 53 actual delegates, all of whom presumably attended; curiously, neither George Henry White nor Judson Lyons were among those pictured, although both were certainly there. Despite its limitations, the book itself provides a rare, intriguing snapshot into the inner workings of the convention itself. [You can view the entire book at the Library of Congress website, downloadable as a pdf file, at https://www.loc.gov/item/00006744/ .]

* * * * * *

GOP faithful in 1900 gathered at this site near the University of Pennsylvania, finally demolished in 2006. Public domain

With renomination all but guaranteed to incumbent President William McKinley, widely but not universally popular among black leaders, the traditional courting of Southern black delegates by various campaigns did not occur in 1900. So black delegates sought to make their presence known at this convention instead by demanding specific planks in the party’s platform, dealing with rising violence against black citizens in the South and the disfranchisement by most Southern states of black voters, among two issues strongly pushed by the new National Afro-American Council, the country’s first broadly-based civil rights organization (about which I wrote my 2008 book, Broken Brotherhood).

Some black delegates even attempted to give to simmering disapproval of the choice of New York Governor Theodore Roosevelt as McKinley’s new running mate, succeeding the late vice president, Garret A. Hobart. But their voices seemed strangely muted in Philadelphia. The highest-ranking black appointee from the McKinley administration, Treasury Register Judson W. Lyons—a member of the Republican National Committee—helped tamp down objections among his black colleagues to Roosevelt, whose inaccurate and offensive published opinion of behavior by black soldiers during the Cuban invasion in 1898 had gained him few friends among black leadership, even after he publicly apologized.

U.S. Treasury Register Judson W. Lyons, a Georgia delegate in 1900. Public domain photo

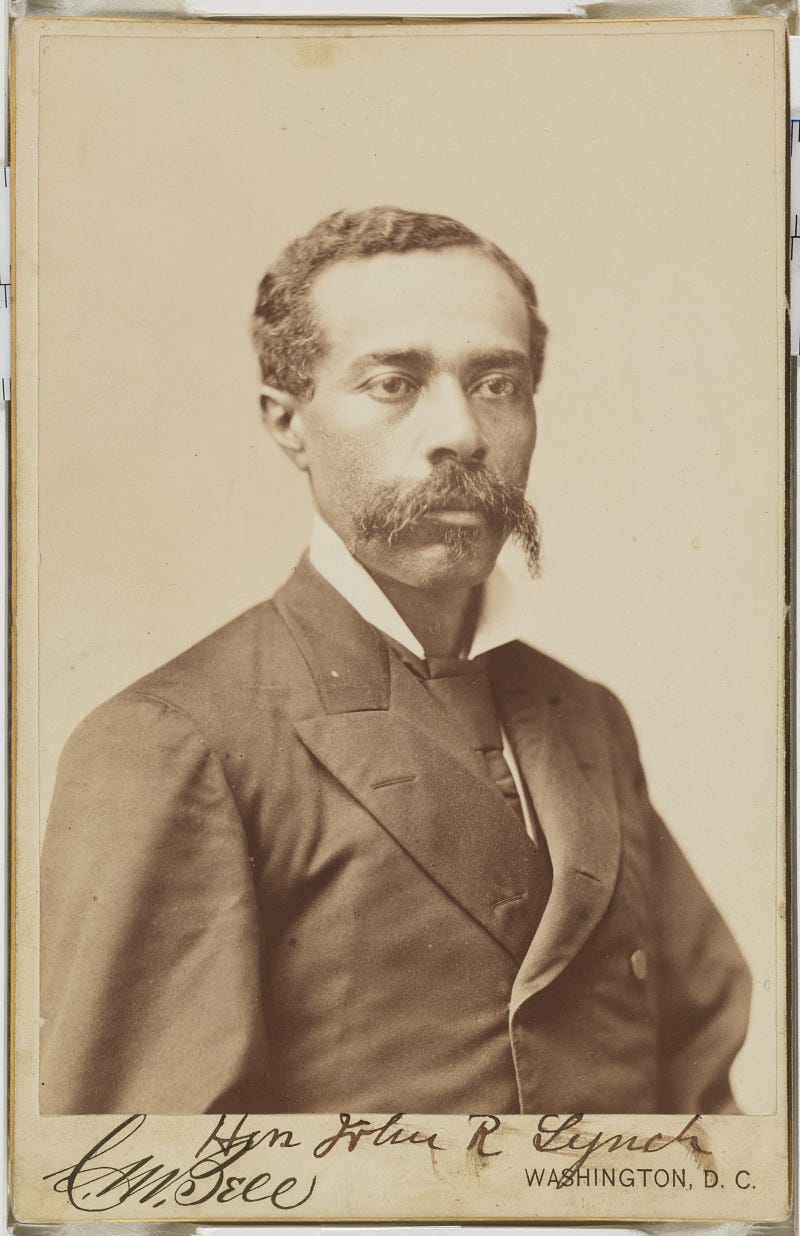

While three former congressmen, Mississippi’s John Roy Lynch and South Carolina’s Robert Smalls and George W. Murray, were present with Rep. George White on the floor in Philadelphia, and unsuccessful congressional candidates continued to serve as regional delegates for years to come, John Lynch was arguably the last black player on the national stage with any truly national presence and reputation and any significant clout within the white wing of the party.

Former Rep. John Roy Lynch, who attended his last convention in 1900. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery

His remarkable career as a delegate had begun three decades earlier, in 1872. In his frank autobiography, Reminiscences of an Active Life (completed in 1939 but not published until 1970), Lynch detailed his careful strategy to win back his seat on the Mississippi delegation in 1900, “which would probably be the last convention I would aspire to be a member of.” Internal party strife within Mississippi had taken its toll on the credibility of longtime party leader James Hill, who soon lost his post on the National Committee. Lynch, currently serving as a high-ranking paymaster in the U.S. Army, and detailed to Cuba, did not even attend the state convention which chose delegates, but his wise planning prevailed. Both he and Hill were chosen, despite their fractured relationship.

After the convention, Lynch sought to restore a measure of harmony to the state party, but admits in his memoir that he was unable to straighten out the difficulties Hill had largely created for himself or later obtain a patronage appointment for him from President Theodore Roosevelt.

Besides Lynch, Hill, Rep. White, and Judson W. Lyons, a number of notable delegates from other Southern states attended the Philadelphia gathering, including Georgia’s state party chairman, William A. Pledger, Henry Lincoln Johnson, John H. DeVeaux, and Georgia political boss Henry A. Rucker; Florida’s veteran delegates, Joseph E. Lee and H. C. Chandler; and Louisiana’s Beverly V. Baranco and Walter L. Cohen. A large group from South Carolina included William Demos Crum, soon to become a high-ranking federal appointee; Edmund H. Deas, and longtime Florence postmaster Joshua E. Wilson. Alfred W. Harris of Virginia and Wesley Crayton of Mississippi were also among the 40 or so black delegates and alternates who had attended the 1896 convention; more than a dozen had attended at least two, so the majority were well experienced in convention ways.

Chief among the veterans were Lynch, who had last appeared in 1892 and attended almost every convention since 1872, and former congressman Robert Smalls, who had attended all but one convention since 1864—when he had actually served as an unofficial honorary delegate, after commandeering a Southern blockade runner and escaping from slavery during the war. Three notable newcomers included Washington, D.C., attorney and newspaper publisher W. Calvin Chase; Memphis, Tennessee, businessman Robert Reed Church; and Kentucky businessman Wallace A. Gaines, now serving as a revenue agent for the Treasury Department.

Kentucky delegate Wallace A. Gaines in 1900. Public domain engraving

W. Calvin Chase, District of Columbia delegate in 1900. Public domain engraving

Robert Reed Church, Tennessee delegate in 1900. Public domain photo

Just three Southern delegations—particularly Alabama (7 delegates), Georgia (8) and South Carolina (10)—accounted for roughly half of all Southern black delegates in 1900. Meanwhile North Carolina, which had sent eight delegates in 1892 and six in 1896, could manage just three delegates in 1900, as a crucial vote loomed on a disfranchisement amendment to the state’s constitution later in the summer. Louisiana, which had sent nine black delegates in 1896, produced fewer than half that number (4), in 1900; Mississippi dropped from nine to five black delegates in the same period.

With fewer delegates in attendance, and with their support not considered as important as in the previous three conventions, the handwriting was on the wall, if not everyone yet perceived it clearly. One chapter in my 2020 book, Forgotten Legacy: William McKinley, George Henry White, and the Struggle for Black Equality (LSU Press), details the dilemma facing the black delegates in Philadelphia and indeed, during the entire 1900 campaign: despite strong support for McKinley’s reelection, there was an increasing sense of discontent and pessimism about the future.

In my next posting, I will describe actual events at the Philadelphia convention itself—and a look forward to the 1904 convention.

Next time: Disappointment prevails in Philadelphia as strong platform planks on racial justice are rejected