African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 9: Reaching a new milestone at Chicago, 1884

This week, I resume showcasing the results of my ongoing research into political activities by African Americans at the nation’s Republican presidential nominating conventions in the nineteenth century, being conducted for my long-planned book on the subject. I will pick up where I left off in April, after accounts of the 1880 convention in Chicago.

Readers may recall that the 1880 GOP nominating convention was the first to feature a black candidate for vice president, Senator Blanche K. Bruce of Mississippi—symbolically offered by former congressman John Roy Lynch of the same state. Bruce was about to complete his term as the nation’s second black U.S. Senator, and even presided briefly over the 1880 convention, as one of the state vice presidents chosen by the convention.

Bruce, of course, had no real chance at the vice presidential nomination, which had already been promised to Chester Arthur of New York—but did have the signal distinction of coming in second in the final vote, with eight votes. It was his last political hurrah in elective office, although he would continue to hold several distinguished appointive positions. By 1884, when both he and Lynch returned as delegates to the party’s convention in Chicago, he would be in the fourth year of his term as Register of the U.S. Treasury—appointed by newly-elected President James Garfield in May 1881, and the first black American to hold that office.

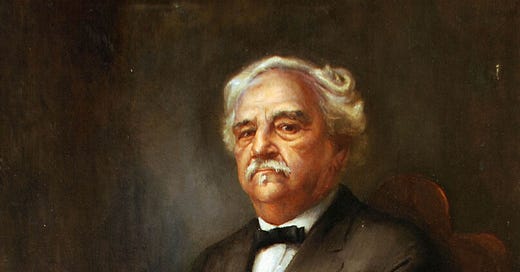

Former U.S. Senator Blanche K. Bruce (R-MS). Public domain photo

During the same interim period, Lynch had won election to his third term as a Mississippi congressman, if awarded the seat only after a lengthy contest against his Democratic opponent in April 1882—the incumbent, James Chalmers, who had fraudulently defeated him in 1876. Although his loss in the general election that year—again to Chalmers—ended his elective career, he would hold several high-ranking patronage positions in the Harrison and McKinley administrations, and would become one of the nation’s best-known black lawyers after passing the Mississippi state bar in the 1890s.

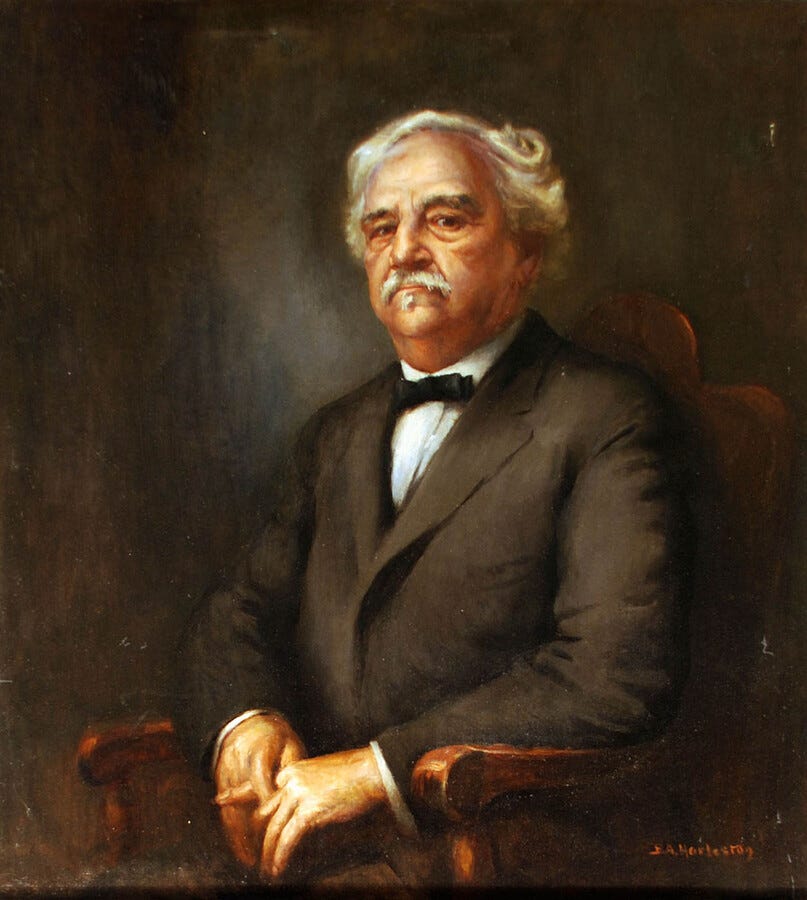

Former congressman John R. Lynch, temporary convention chairman in 1884. Public domain photo

Bruce and Lynch were among nearly 70 African American delegates selected by their state parties to the 1884 convention, including four other black delegates from Mississippi—former Secretary of State James Hill and veteran Port Gibson postmaster Thomas Richardson among them. And most of them were experienced as delegates; of the 68 voting delegates identified so far as black in 1884—the largest number yet at a Republican convention—more than half were veterans of at least one previous convention, having served either as voting delegate (27) or as an alternate delegate (11).

Rep. James E. O’Hara (1844-1905) (R-NC), delegate to 1884 convention. Courtesy New York Public Library

Only one sitting Congressman—North Carolina’s James E. O’Hara, elected in 1882—was an actual delegate in 1884, although ex-Senator Bruce and former congressmen Lynch and South Carolina’s Robert Smalls represented their states. At least 48 alternate delegates were named in 1884—including at least one future congressman, Thomas E. Miller of South Carolina; how many actually attended, however, cannot be determined from convention records.

Thomas E. Miller, alternate delegate in 1884. Courtesy Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture

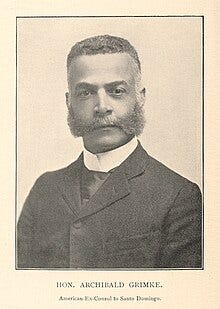

Among other notable African Americans with convention connections, all newcomers in 1884, were a former U.S. minister to Liberia, J. Milton Turner of Missouri, an alternate delegate; and three future U.S. diplomats: delegate Judge Mifflin W. Gibbs of Arkansas (consul to Madagascar in the 1890s); alternate delegate Archibald H. Grimke of Massachusetts, twice U.S. consul to Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic) in the 1890s; and alternate delegate Christopher H. Payne of West Virginia, who would later serve as Consul General to the Danish West Indies after 1903.

Archibald Grimke, alternate delegate in 1884. Public domain photo

J. Milton Turner, ex-Minister to Liberia, an alternate delegate in 1884. Photo courtesy Kingdom of Callaway Historical Society

Christopher H. Payne, alternate delegate in 1884. Public domain photo

A decade later, Payne, a minister and teacher studying to become a lawyer, would become the first black man elected to West Virginia’s legislature in 1896. He shared that distinction with another alternate delegate in 1884, currently serving his second term in the Massachusetts state legislature—and among the first black men ever elected to more than one term in that state’s lower house: Julius Caesar Chappelle (1852-1904).

Julius C. Chappelle, alternate delegate in 1884. Courtesy State Library of Massachusetts

If still barely known outside Boston, Chappelle was a unique figure in Massachusetts politics—a former slave, transplanted from Georgia, who worked as a barber, and who defeated a series of better-known white figures to gain his legislative seat. Chappelle would not gain national fame from his brief exposure to his party’s national convention arena; after retiring from the state house, he would not be able to gain the federal patronage appointment he sought—limited perhaps by his lack of higher education. But he would play a key role in state party politics on its state committee after 1889, serving as its chairman in his third term.

In Chicago, he may well have crossed paths with another young former slave who played a behind-the-scenes role in Chicago, canvassing votes among black delegates for the eventual nominee, James G. Blaine. John Francis Quarles (1847-1885), son of an Atlanta minister, had gained an early foothold after graduating from Pennsylvania’s small Westminster College, encouraged personally by influential Senator Charles Sumner. Admitted to the Georgia bar in the early 1870s, he soon won respective appointments as U.S. consul to Port Mahon, in Spain’s Minorca island, and Malaga by Presidents Grant and Hayes.

In Chicago, according to the New York Times (“Random Notes of the Contest,” June 3, 1884), Quarles was busy working as a grassroots organizer “with considerable effect” for the Blaine campaign among Southern black delegates as the convention opened that same date. Black delegates represented about 8 percent of the conventions’s total (820), and in a close race, certainly presented a desirable target.

But the majority of the South’s 68 black delegates clearly preferred President Arthur—signaled by the unanimous or near-unanimous votes for Arthur on the first three ballots from Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia, which boasted 44 of the 68 black delegates—and gave Arthur 132 votes on the first ballot, compared to Blaine’s total of just 10 from those eight states.

However persuasive Quarles’s efforts may have been with Arkansas and Texas delegates—the only two Deep South state delegations to prefer Blaine over President Arthur on the opening ballot—and perhaps some lesser success with delegates from Alabama, Louisiana, and Tennessee, he had little success with strongly pro-Arthur delegations elsewhere, which held out for Arthur until the bitter end.

But national support for Arthur’s renomination among black leadership had already begun to flag, as the President’s campaign lost steam. The national organization claiming to represent most African American voters failed to endorse Arthur enthusiastically at its separate meeting in Chicago during the convention—attended by 72 black leaders, “most of them delegates,” according to the Washington Evening Star (June 3, 1884)—and could only muster a compromise resolution “declaring that President Arthur’s administration has been wise and conservative.”

* * * * * * *

Frederick Douglass, the formidable orator and abolitionist leader serving as the District of Columbia’s first black Recorder of Deeds (appointed by the late President Garfield), was not a delegate to the convention—but still turned up in Chicago to address a meeting of black delegates, bringing along an entourage of some 50 Washington black leaders. The Washington Evening Star’s account of the speech (June 4, 1884) was both humorous and pointed, at one point responding to criticism from an unidentified man over his recent marriage to his second wife, who was white (“I said, that’s a mistake; you are satisfied with the color of your wife and I am with mine. That’s as far as your business goes …”).

Whatever his private feelings, Douglass neither mentioned nor endorsed a political candidate, but did unequivocally endorse fair treatment for black citizens: “We are American-born citizens and we only ask to be treated as well as you treat aliens. Give us fair play and let us alone. Good night.”

The party’s platform had already disappointed many by not specifically referring to a recent decision by the U.S. Supreme Court to strike down most provisions of the 1875 Civil Rights Act—still a sensitive subject to many black leaders—but focusing instead on protecting voting rights for all Americans, particularly in the South, pledging “to promote the passage of such legislation as will secure to every citizen, of whatever race and color, the full and complete recognition, possession and exercise of all civil and political rights.”

It did single out the Democratic Party as “guilty” of current fraud and violence in the South, in its final two paragraphs:

The perpetuity of our institutions rests upon the maintenance of a free ballot, an honest count,

and correct returns. We denounce the fraud and violence practised by the Democracy in

Southern States, by which the will of a voter is defeated, as dangerous to the preservation of free

institutions; and we solemnly arraign the Democratic party as being the guilty recipient of fruits of

such fraud and violence.

We extend to the Republicans of the South, regardless of their former party affiliations, our

cordial sympathy; and we pledge to them our most earnest efforts to promote the passage of

such legislation as will secure to every citizen, of whatever race and color, the full and complete

recognition, possession and exercise of all civil and political rights.

Not present in Chicago was another outspoken black Republican leader who had often visited previous conventions as an interested party: John Mercer Langston, currently serving as U.S. Minister to Haiti. Langston, who had once advised the late Senator Charles Sumner in drafting the 1875 Civil Rights Act, would become politically active again after his return to the United States in 1885, finally winning a contested seat for Congress from Virginia in 1890.

And present, if playing a far quieter role as a Mississippi delegate, was former Senator Blanche K. Bruce, now serving as the Register of the U.S. Treasury. Urged to seek the post of temporary chairman of the convention, against a white former governor of Arkansas, Powell Clayton, Bruce had declined to do so, clearing the way for his black Mississippi colleague, former congressman John Roy Lynch, to run for the largely ceremonial post.

Lynch would do so, with characteristic energy and surprising support from a number of white Republican leaders, including a youthful Theodore Roosevelt. The results would astonish many who had expected Clayton—a controversial former U.S. Senator and key Southern supporter of James G. Blaine—to win the post with ease.

In next week’s entry, I will examine the complicated scenario which ensued, elevating Lynch to sudden national prominence at age 37.

Next time: Riding a wave of popularity to help lead his party’s convention