African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 20: Renominating Teddy Roosevelt in Chicago, 1904

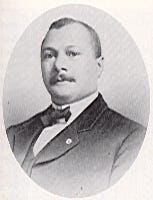

The 60-odd black Republican delegates who joined white convention colleagues in Chicago in 1904 were committed to the renomination of President Theodore Roosevelt, who had assumed office in September 1901 after the assassination of William McKinley. Their levels of enthusiasm probably varied from resigned to lukewarm, but for at least one delegate—Baltimore, Maryland, city councilman Harry S. Cummings—the duties of delegate held a special meaning.

Cummings had been selected to deliver the final seconding speech after Roosevelt’s actual nomination. Well-known as an orator and a skilled lawyer, Cummings gave what is often concisdering the most stirring speech in convention history, describing the president as “above all things, a true, honest, earnest and patriotic American citizen … a leader of unflicnhing courage, a man of wisdom, a man of action.”

Maryland delegate Harry S. Cummings, who seconded Roosevelt’s nomination. Public domain photo

Cummings, a newcomer to duties as delegate, was certainly not the best-known of the convention’s black delegates, but his record as the first black graduate of the University of Maryland’s law school and the first city councilman in Baltimore had certainly embellished his credentials in Maryland in recent years, and as a rising star in the state’s Republican party. He had already served as an alternate delegate at large from Maryland in 1900.

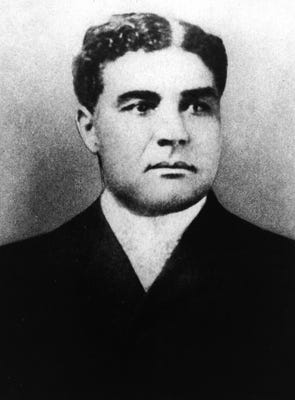

Not yet 40, he was in the middle of his career as a public servant, to be elected to three more terms on the council before his sudden death from a stroke a decade later. There were many far more experienced delegates available—including such national figures as Treasury Register Judson Lyons, former judge and diplomat Mifflin Gibbs of Arkansas, renowned Tennessee lawyer James C. Napier, and former congressman Henry P. Cheatham of North Carolina, to name just four. But Cummings may have been selected, in part, for his youth and eagerness to second Roosevelt’s nomination, and for his very lack of federal appointments, representing the future.

Roosevelet “is a just man, and believes that men should be judged by merit and merit alone,” Cummings said. “[W]ith a vision unclouded by bias or prejudice, he sees through the outer clay clad in different hues, the man within, and there beholds the image of the Divine Master, indicating the Fatherhood of God and the Brotherhood of Man.”

Interrupted by frequent applause, the speech was certainly a high point in the otherwise rather quiet convention, and was reprinted in its entirety by the New York Times [“Roosevelt and the Negro. Colored Orator Says President Sees the Man Through the Skin,” June 24, 1904). Its text follows here, taken from the convention’s Official Proceedings:

xx

Harry Cummings was the only black speaker whose remarks were noted in the text of the 1904 Official Proceedings. But Cummings’ speech, notable as it was, did little to move the convention toward dealing emphatically with critical issues facing the nation’s African Americans, particularly lynching, which was all but ignored.

The party’s platform did contain a plank dealing with the nagging issue of disfranchisement, one which had gradually deprived most black Southern voters of the right to vote since the 1890s, and gave some black leaders hope that a future Congress might seek to punish Southern states by reducing their future representation in Congress—an issue completely avoided in 1900, before the redistricting required after the 1900 census.

But the 1904 plank was still somewhat vague, simply “favoring Congressional action” to determine whether voters had been harmed unconstitutionally—and to take action only after that determination was made. “We favor such Congressional action as shall determine whether by special discrimination the elective franchise in any State has been unconstitutionally limited,” read the platform, “and, if such is the case, we demand that representation in Congress and in the electoral college shall be proportionately reduced as directed by the Constitution of the United States.”

As analyzed by a special correspondent for the Washington Evening Star [“Reducing Representation,” June 22, 1904], passage of the plank was especially promising to black Republicans in Southern states battling the growth of the lily-white movement, especially after Louisiana’s “black and tan” delegation managed to defeat—or at least achieve parity with—the state’s lily-white faction in a credentials dispute. The passage of the suffrage plank “further encourages the colored men here with the idea that the day is not far distant when they will be able to vote all over the South and to have their votes counted.”

That day, of course, lay sometime in the future, and depended on the commitment of white Republicans in Congress to continue the battle against poll taxes and literacy tests aimed largely at black voters, and presupposed that the Supreme Court would one day overturn the obstacles erected by Southern Democratic leaders to black registration and voting.

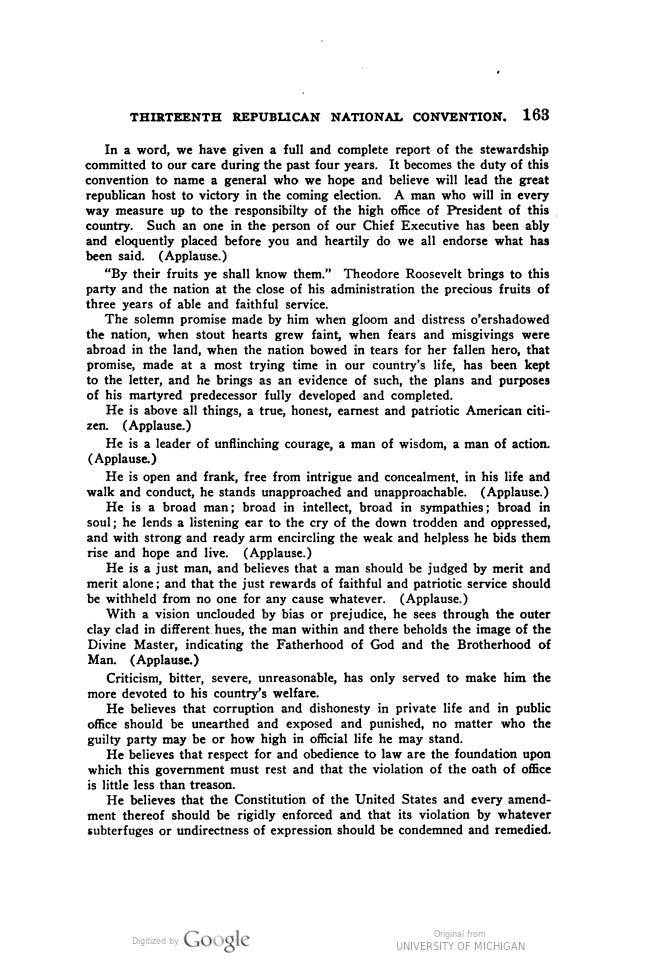

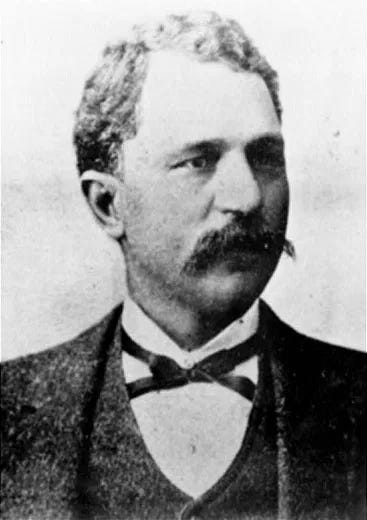

These new obstacle had already taken their toll in states like North Carolina, which sent just two black delegates in 1904—former congressman Henry Cheatham (1889-1893) and longtime Wilson postmaster Samuel H. Vick—compared to eight in 1892 and six in 1896. Vick, who had been Wilson’s postaster for most of the past 15 years, was a prominent and affluent real estate investor in his county seat; appointed by both Presidents Harrison (1889) and McKinley (1898), he had been allowed to continue by Roosevelt in 1902. Like Cheatham, he was still on good terms with white Republican leaders—and was allowed to register to vote under the resttrictive new law in 1902.

Samuel H. Vick, North Carolina delegate in 1904. Photo courtesy blackwideawake, https://afamwilsonnc.com/ .

Henry P. Cheatham, North Carolin delegate in 1904. Public domain photo

But comparatively few other black voters in North Carolina—or indeed, in many other Southern states—would be accorded the same privilege. Even North Carolina, a proudly biracial party since 1868, would send no more black delegates to the convention for decades to come. Passage of the literacy amendment to that state’s constitution in August 1900 had already reduced black voting numbers to a pitiful shadow of its 1890s total—about 5,000, from a total exceeding 100,000 voters just a few years earlier—and blacks were no longer considered worthy of the distinction until the 1930s. The state’s last black congressman, George H. White, had stepped down in 1900, and no black would be sent back to Congress from the state again until 1992.

Almost all other Southern states would continue to send some black delegates to Republican conventions, however, for another decade and more, particularly Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, whose delegations remained racially mixed even after the First World War. Black candidates for Congress, for instance, would continue to appear in state delegations, especially South Carolina, for another decade.

But for most black Republicans in the South, the glory days were now ending.

* * * * * * *

The black delegates serving in 1904 included a markedly smaller percentage of federal appointees than at any recent GOP convention, reflecting Roosevelt’s lack of enthusiasm for black appointees. Just two postmasters—Thomas S. Harris of Liveoak, Florida, and Louis P. Piernas of Bay St. Louis, Mississippi—and four mid-level patronage reappointments from the McKinley era appeared, along with just three new appointees, including Dr. William D. Crum, a physician recently nominated as customs collector at Charleston, South Carolina.

Black delegates did receive a smaller number of choice committee appointments at the 1904 convention, even as their national influence was beginning to fade. Two black members were named to the Republican National Committee—Georgia’s Judson W. Lyons, reappointed, and newcomer Walter L. Cohen of Louisiana, effectively replacing the South’s other recent member, Mississippian James Hill, who had died in 1903.

Walter L. Cohen of Louisiana, 1904 delegate to GOP convention. Public domain photo

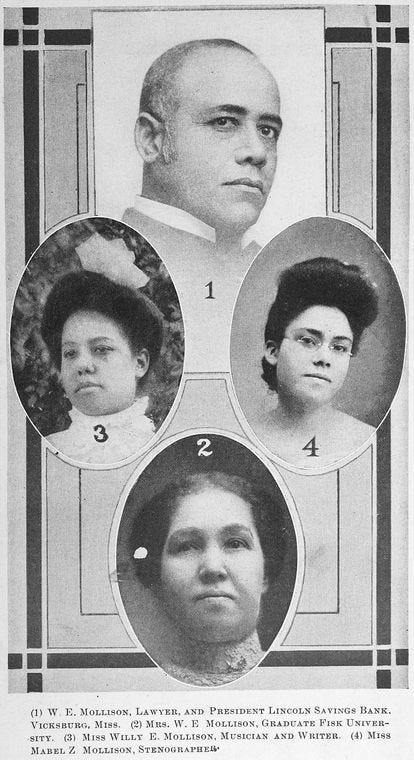

Four black delegates were named to the Resolutions Committee—Andrew N. Johnson of Alabama, J. Madison Vance (Louisiana), W. E. Mollison (Mississippi), and Edward J. Dickerson (South Carolina)—and to the Credentials Committee: Nathan H. Alexander of Alabama, Walter Cohen of Louisiana, Wesley Crayton of Mississippi, and John F. Cook of the District of Columbia.

Andrew N. Johnson, Alabama delegate in 1904. Public domain photo

Mississippi delegate W. E. Mollison in 1904, shown with wife and daughters. Public domain photo

Mississippi delegate Wesley Crayton in 1904. Public domain photo

Another five delegates were appointed to serve on the Committee on Permanent Organizations. They were Ferd Havis of Arkansas, a wealthy businessman whose nomination as postmaster of Pine Bluff had notoriously failed to clear the Senate in 1898; John F. Cook of the District of Columbia, William H. Matthews of Georgia, Thomas Richardson of Mississippi, and Charles M. Ferguson of Texas.

Ferd Havis of Arkansas, 1904 delegate to the GOP convention. Photo courtesy Encyclopedia of Arkansas

In addition, two black delegates served on the Rules Committee: Florida’s Mark S. White and Mississippi’s Ephraim H. McKissick.

This concludes my look at the 1904 Republican convention, and with it, the first 36 years of African American political participation in U.S. presidential conventions. I would enjoy hearing from readers with their thoughts on my research so far—and the forthcoming book I still plan to write on the subject.

My next blog entries will turn to examinations of other historical events, including a look back at World War I—when my late grandfather fought in France as a machine gun regiment—and at more recent events.