African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 18: Disappointment prevails in Philadelphia in 1900 as platform planks on racial justice are watered down

In his autobiography, written in the late 1930s, John Roy Lynch still displayed a near-encyclopedic grasp of political currents and fissures within his beloved Republican party. The 1900 presidential convention, at which he served as the senior African American delegate on the Resolution Committee’s subcommittee on platform, was in many ways his political swan song, and he devotes most of a very detailed chapter to the unfortunate outcome of what had once promised to be a much brighter episode.

Members of the new National Afro-American Council had pushed two strong planks on racial justice—one explicitly condemning lynching (and thus helping bolster the chances of Rep. George White’s bill on the subject), and another aimed at punitively reducing Congressional representation in states which disfranchised their black voting populations. Both were hot topics, and in a perfect world, both should have passed easily—but circumstances did not go according to plan in the summer of 1900.

Lynch was one of three black members of the subcommittee, along with Georgia’s Henry Rucker and South Carolina’s Edward J. Dickerson. The former congressman was expected to take the lead on both the disfranchisement and lynching planks, while Rep. George White—whose anti-lynching bill was currently trapped in the House Judiciary Committee—was available as a backup if the subcommittee needed further testimony.

But when Lynch introduced his substitute plank on disfranchisement, he was outmaneuvered—or double-crossed—by delegate Lemuel Quigg of New York, who had compiled what became the final draft and pushed through vague and anodyne language “to prevent discrimination on account of race or color in regulating the elective disfranchise,” but without any solution or penalty. In a separate attempt to force the convention to take a stand on reducing future Congressional representation of Southern states which had disfranchised their black voters, Lynch’s substitute language was voted out of order, and he was never permitted to deliver a strongly-worded speech on the subject.

Combined with the platform’s toothless plank on lynching—not explicit at all, and far less inspiring than the 1896 plank—the once-promising situation suddenly became one of despair. Its vague wording—”The American Government must protect the person and property of every citizen wherever they are wrongfully violated or placed in peril.”—made no reference at all to violence against black citizens, and did nothing to assist Rep. White in his ongoing battle to force a floor vote on his anti-lynching bill.

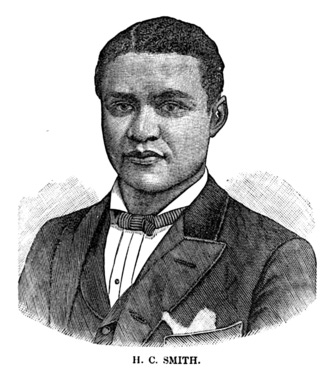

The uproar in the black press over Lynch’s apparent failure to accomplish his assigned goals was led by the acerbic editor of Cleveland’s black Gazette weekly, a former state legislator whose articulate fury knew no bounds, no matter how misinformed or misguided: Harry Smith. According to Smith, who often picked pointless fights with other editors or with black leaders who misstepped (at least in his eyes), Lynch alone was “wholly responsible for the mutilation and practically the ruination of the Afro-American council’s resolution.”

Harry C. Smith, editor of the black Cleveland Gazette, in 1900. Public domain photo

Smith had, of course, sponsored the nation’s strongest anti-lynching law in Ohio just four years earlier, and assumed—however naively—that passing a national law on the subject was equally possible, if the will were strong enough. But having never served in Congress, nor as a delegate to his party’s convention, he was unable to make a seasoned judgment on the difficulties involved. Had he bothered to talk to Lynch first, he might at least have understood what happened and why.

Lynch’s efforts were noted by the mainstream white press (“The Negroes’ Desire,”Philadelphia Times, June 21), including his attempt to magnify his voice by standing on a chair, but little context was provided for his exclusion from speaking.

Years later, Lynch printed the prepared text of the lengthy speech he was never allowed to give on the disfranchisement of black voters in the South, part of which appears below:

“… It will be some satisfaction and consolation to Southern Republicans who are deied acess to the ballot box through an evasion of the national constitution, to know that if they are to be denied a voice in future national conventions of the party to which they belong, becuase they are unable to make their votes effective at the ballot box, the [Democratic] party through or by which they are thus wronged will not be allowed to take advantage of and enjoy the fruits thereof.

They will at least have the satisfaction of knowing that if they cannot vote themselves, others cannot vote for them, and thus appropriate to themselves the increased representation in Congress and the electoral college to which the state is entitled, based uppon their repsresentative strength. [italics added by author]

The colored Americans ask no special favors as a class and no special protection as a race. All they ask and insist upon is equal civil and political rights and a voice in the government, state and national, under which they live.”

As Lynch wanted to point out, the upcoming disfranchisement of black Republicans in North Carolina—if as feared, the statewide constitutional amendment was amended in August to deny the ballot to illiterate voters wbut grant white voters an exemption based on ancestry (the hated “grandfather clause”)—warranted a direct warning shot to the Democrats who were promoting it. He would have begged fellow Republicans “not to cloud the magnificent record which this grand organization has made” by deserting the very voters they had elevated to citizenship.

The so-called Crumpacker amendment—named for the Indiana representative who sponsored it, Judge Edgar Crumpacker—was still looming in Congress, and would have done just what Lynch sought: effected a reduction in Southern representation when reallocating congressional seats on the basis of the 1900 census results. Its advance rejection by the party convention almost certainly signalled its eventual doom in January 1901, when it failed to capture a majority of the Republican-dominated House.

For Rep. George White, who had hoped fervently for a boost to his own anti-lynching bill in Washington, the twin defeats were equally disappointing. His only recorded remarks during the convention came in seeking a re-reading of convention Rules 1 and 12, in an effort to publicly shame those who sought to silence Lynch. By the end of the summer of 1900, after passage of the hateful constitutional amendment in North Carolina, he declined renomination to a third term and prepared to step down at the end of his term in March 1901, leaving Congress without any black membership.

* * * * * * * *

There were some bright sposts, to be sure, and a handful of successes for individual black delegates in Philadelphia. Six black members were selected to serve on the Committee on Credentials: Herschel Cashin of Alabama, Henry L. Johnson (Georgia), Wesley Crayton (Mississippi), John Fordham (South Carolina), Henry Ferguson (Texas), and W. Calvin Chase )District of Columbia).

Another four were selected to serve on the important Rules Committee, including North Carolina’s Robert Russell, Florida’s Henry Chandler, Mississippi’s R. A. Simmons, and Mack M. Rodgers of Texas.

Three black delegates were named to the Committee on Permanent Organizations: James Peterson (Alabama), Ferd Havis (Arkansas), and Charles Ferguson (Texas)—in addition to the previously-named John Lynch, Georgia’s Henry Rucker, and South Carolina’s Edward J. Dickerson on the Committee on Resolutions.

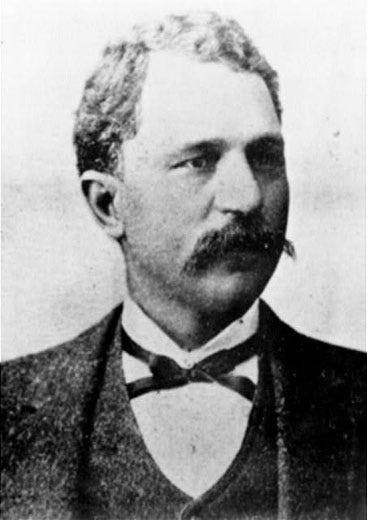

Ferd Havis, Arkansas delegate in 1900. Courtesy Arkansas Archives

Among those chosen to serve on the post-convention delegation to visit President McKinley in Canton a month later and present his formal nomination were four black delegates: Florida’s Joseph Lee, Georgia’s William Pledger, South Carolina’s Edmund H. Deas, and the District of Columbia’s W. Calvin Chase.

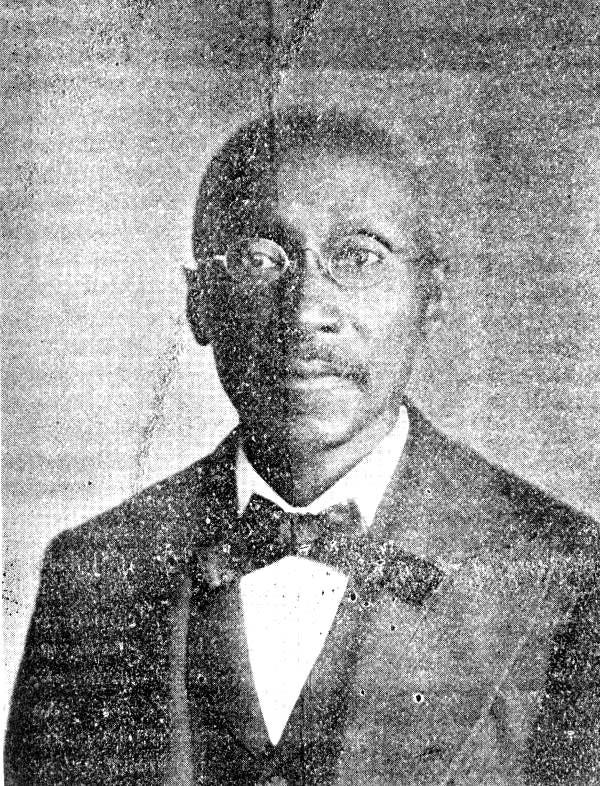

Joseph E. Lee, Florida delegate in 1900. Public domain photo

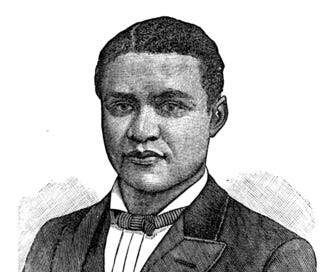

William A. Pledger, Georgia delegate in 1900. Public domain engraving

W. Calvin Chase, District of Columbia delegate in 1900. Public domain engraving

Edmund H. Deas, 1900 delegate from South Carolina. Public domain

All can be clearly identified in the large photograph from the Cleveland Plain Dealer, seen below:

The 1900 convention committee delivers its notification to William McKinley. Public domain photo

Enthusiasm for William McKinley was already waning somewhat, especially among certain activist black leaders who were disappointed with his failure to act on important issues. This despite the fact he had appointed hundreds of blacks to low- and medium-level posts during his administration—including his commissioning of more than six dozen black command officers in the Army, the first in U.S. history, in the year after the Spanish-American War.

But there was far less enthusiasm for his new running mate, Roosevelt, among black voters. Many were openly disenchanted with his past statements about the alleged cowardice of black soldiers under fire. It was ironic, then, that only two black delegates would agree to serve on a separate committee dispatched to notify Gov. Theodore Roosevelt of his nomination as vice president: the relatively obscure John Cooke of Louisiana and the somewhat better-known Charles Ferguson of Texas.

Would Roosevelt become more like McKinley on racial issues—or less open than his new boss—once inaugurated as vice president? He was a question mark. No one could guess.

* * * * * * *

On balance, the first McKinley administration had been the most positive ever for black citizens, especially in terms of jobs provided to black men, and a handful of women. Nearly half of the black delegates in 1896 had gained significant federal appointments under McKinley, and many of them were enthusiastic delegates in 1900. As a result, it was no surprise that most black Republican leaders lined up steadfastly behind him during the fall campaign—including almost all of the leadership of the technically-nonpartisan National Afro-American Council.

Even as black Republicans lost political ground in the South, and as more and more northern blacks began gravitating toward the Democratic party, McKinley remained their chosen leader, with no challenger in sight.

As black Republicans prepared to return to Chicago for years later, to nominate a successor to William McKinley—who was not likely to seek a third term—a new generation of black leaders from across the country was quietly preparing to take control. Not all of the 1900 delegates would return; some, like Lynch, would step aside, while at least four others—especially Georgia’s William Pledger, James Hill of Mississippi, and David Abner and Henry Ferguson of Texas, would die in the meantime.

Of the 60 or so black delegates to be chosen in 1904, only about half had previously served as delegates—and far fewer were active postmasters or federal job-holders. I will explore the reasons why in two weeks.

My next entry will take a quick detour from book research to remember two long-lost friends—fellow journalists—and reclaim their affectionate history, after two decades apart.

Next time: Jim & Susie, we hardly knew ye

.jpg)