African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 13: In 1892, Minneapolis offers a new setting for a party looking forward

Incorporated just 25 years earlier, Minneapolis was already among the nation’s 20 largest cities—with 165,000 residents—when Republicans gathered there for their presidential nominating convention in 1892. Together with twin city St. Paul, Minnesota’s largest city was a flourishing center for iron manufacturing interests—as well as grain and timber—when the mammoth Industrial Exposition of 1886 spurred building of the city’s Exposition Building.

Exposition Hall, Minneapolis, site of the 1892 Republican convention. Photo courtesy www.Mnopedia.org

Republicans were generally united behind incumbent President Benjamin Harrison as they prepared to renominate him, although some holdouts like Rep. John Mercer Langston of Virginia openly preferred perennial candidate James G. Blaine, the unsuccessful 1884 nominee who had recently resigned as Secretary of State. Other Southern black delegates were said to be disappointed that former Michigan governor Russell Alger had declined to be a candidate again.

Langston was one of at least 74 black delegates named to the Minneapolis convention, along with at least 74 black alternate delegates. (Both numbers, for black delegates and alternates, set a new record for the party’s quadrennial convention, reversing a significant dip in 1888.) He was rumored, in fact, by the New York Times as about to be chosen as temporary chairman of the convention—continuing a tradition set by former Rep. John Roy Lynch of Mississippi in 1884—until his open support for Blaine became widely known, after which he was quietly dropped as a candidate.

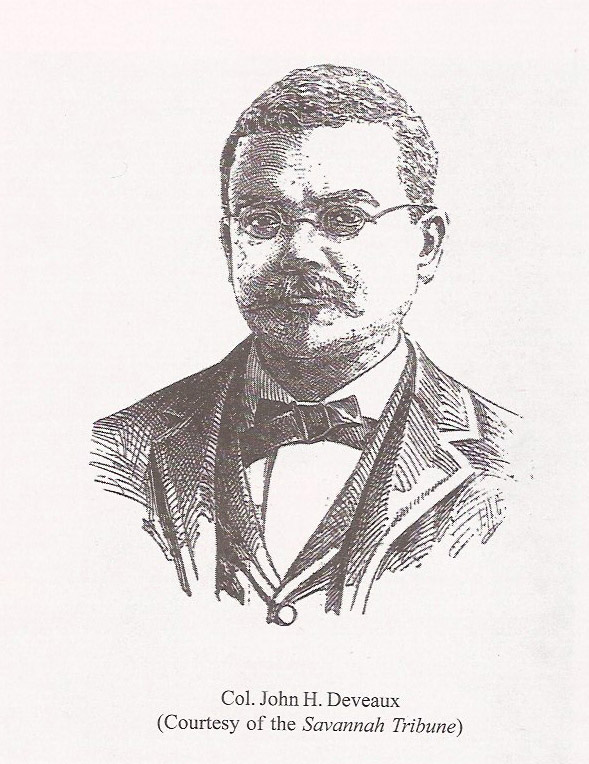

Most of the black voting delegates this time were newcomers. There were perhaps 30 veterans of previous conventions among their ranks in 1892, including both Langston and Lynch; William A. Pledger, Robert Wright, Athens postmaster Madison Davis, John Q. Gassett, and John H. Deveaux of Georgia; Norris Cuney, Charles Ferguson, Mack Rodgers, and Alexander Asberry of Texas; Wesley Crayton, James Hill, and George F. Bowles of Mississippi; Mifflin Gibbs of Arkansas, John Dancy of North Carolina, Perry Carson of the District of Columbia, and Alfred W. Harris of Virginia.

John H. Deveaux, Georgia delegate in 1892. Public domain photo

Perry H. Carson, longtime delegate from the District of Columbia. Public domain illustration

South Carolina’s delegation, which featuredh the single largest number of black voting delegates at 11, had just three voting members with previous experience—delegates Paris Simpkins, Edmund Deas, and Edward J. Dickerson. Three more of its alternates had served as alternates at least once before: at least three, including former Congressman Robert Smalls, himself a previous delegate, and congressional candidate Dr. Joshua Ensor.

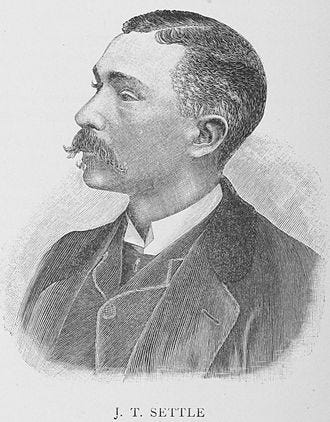

There was also a wealth of national political experience among their ranks. Two sitting congressman—Rep. Langston and North Carolina’s Rep. Henry P. Cheatham—attended the convention as delegates, along with three former congressmen: Lynch, Smalls, and North Carolina’s James E. O’Hara, another alternate delegate. Many were recent former state legislators, including Alexander Asberry of Texas, Hugh Cale of North Carolina, and Josiah T. Settle of Tennessee.

Josiah T. Settle, Tennessee delegate in 1892. Public domain photo

Hugh Cale, North Carolina delegate in 1892. Photo courtesy Elizabeth City State University

Two other delegates were among the first ever elected to their respective city councils: Wesley Crayton in Vicksburg and Harry S. Cummings in Baltimore, Maryland.

Harry S. Cummings, Maryland delegate in 1892. Public domain photo

* * * * * * *

Henry P. Cheatham, running for a third term in the U.S. House from North Carolina’s “Black Second” District, had successfully nominated more than a dozen black postmasters in that rural district since taking office in 1889. He was understandably proud of those achievements and of his relationship with President Harrison, and took the floor at the convention to second the President’s renomination.

“On behalf of the Republican party in North Carolina and the 8,000,000 Negro citizens of the United States, whose progress and development in twenty-six years have surprised the world, I rise to second the nomination of the orator gallant soldier, and one of the ablest and purest statesmen who ever lived to advance the annals of the American history,” Cheatham began.

Four years ago, Mr. President, when the flag of the grand old party was trailing in the dust and her cause had been consigned to the narrow channels of the grave of defeat, when the leaders of the party were despondent, scattered and confused—when it seemed almost impossible to find a Moses to lead the party out of the dark valley of Democracy—Gen. Benjamin Harrison came and more than triumphantly led the party to success and victory. [Applause] Since then his record and his acts have received the highest commendation by the people of this country, of every party. Renominate Benjamin Harrison and you will not only honor yourselves but will insure success and victory in November next. [Applause]

Cheatham’s enthusiasm notwithstanding, the President would manage to gain a narrow victory on the first ballot—with more than than 530 delegates out of 904 cast. The only major surprise on that ballot was the closeness of the runnerups’ tallies—perennial candidate James G. Blaine at 182 and a fractional vote, to exactly 182 for the man who had declared himself not in the running at all: William McKinley.

The Southern delegations provided roughly a third of Harrison’s winning votes, with Arkansas, Florida, and Georgia unanimous—49 votes, including their 21 black delegates—and most of the rest favoring Harrison by varying margins. Only Virginia’s delegation—led by John Mercer Langston—gave Blaine a majority, by 13 to nine for Harrison, although Louisiana split its vote in half, with eight each for Harrison and Blaine.

Most Southern black delegates appeared to favor Harrison, although it is not possible to determine from convention records exactly how many of the 74 black delegates voted for President Harrison’s renomination. A quick study of the two Southern states whose individual votes were reported after routine challenges indicates that most—if not quite all—cast them for Harrison. In North Carolina, all but one of the eight black delegates followed Cheatham’s lead to favor the incumbent President; the lone holdout, ironically, was Halifax postmaster Jonathan Hannon, appointed by Harrison, who daringly chose McKinley.

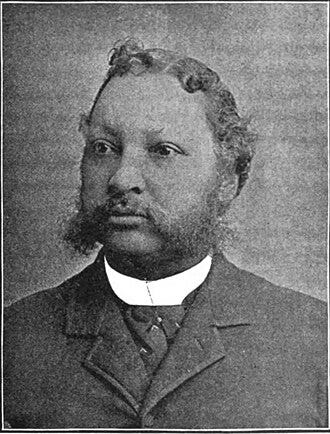

Most of South Carolina’s 10 black delegates chose the incumbent; only Samuel Smith favored McKinley, while three black delegates held out for Blaine, the sentimental favorite from 1884. The two black delegates from the District of Columbia, Perry Carson and Andrew Gleason, also favored Blaine.

Mississippi delegate John Lynch, who had been appointed by Harrison in 1889 as fourth auditor of the U.S. Treasury Department, almost certainly cast his ballot for Harrison, although he never specifies it in his 1939 memoir. The continuing intraparty squabbles and intrigue within the Mississippi party leadership, however, are carefully detailed. Even though Harrison had appointed party leader James Hill as postmaster at Vicksburg—a controversial and unpopular move—Hill decided, according to Lynch, to push for an anti-Harrison delegation in 1892 “not on account of any objections to Harrison, but because he hoped and believed that through the defeat of Harrison the power and influence of [Blanche K.] Bruce and [John] Lynch would be destroyed.”

Hill’s somewhat Machiavellian efforts were unsuccessful, and he chose to lead a separate anti-Harrison slate to the Minneapolis convention, where he was among a handful of delegates added to the regular delegation through the influence of Pennsylvania Senator Matthew Quay, who chaired the Republican National Committee on which Hill already served. The outcome was that Mississippi’s vote, ‘tho split, tilted toward Harrison, with 13.5 votes, to 4.5 for Blaine; of its 10 black delegates, therefore, at least half voted against Hill’s initiative.

Hill himself would soon lose his treasured Vicksburg postmastership, after Harrison’s defeat by Cleveland in the fall election, but his party intrigues would continue. And almost against the odds, he would continue to demand—and receive—patronage appointments until his death in 1903.

James Hill, Mississippi delegate in 1892. Public domain photo

Despite his reckless behavior, Hill would retain Mississippi’s membership on the Republican National Committee, joined in 1892 by two other black members: Norris Cuney of Texas and Perry Carson of the District of Columbia.

Somewhat surprisingly, those black politicians targeted by Hill—notably Blanche Bruce and John Lynch— were also eventually successful in patronage efforts, although all would now have to wait until President Cleveland left office in 1897 to do so.

Next time: Minneapolis proves a pleasant change of pace for Republicans