African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 15: Gathering in Saint Louis, Republicans seek a comeback in 1896

Choosing a site as far south as Saint Louis for its presidential nominating convention posed a strategic risk of sorts for the Republican Party. Missouri, a slave state which remained technically neutral but sided with the Union during the Civil War, had been a major flash point for much of the war, spending years under martial law, according to historical accounts.

“Populated by both Union and Confederate sympathizers … [Missouri] sent armies, generals, and supplies to both sides, maintained dual governments, and endured a bloody neighbor-against-neighbor intrastate war within the larger national war,” summarizes the Wikipedia article. A competing Confederate government-in-exile fled to Texas for the duration of the war. Then a statewide law ended slavery in January 1865, long before the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was enacted.

By the late 1890s, Saint Louis had become the nation’s fourth-largest city, with around 600,000 residents, including the ninth-largest U.S. concentration of black citizens—around 35,000, just after Atlanta’s total. The city’s very active black community had gained at least a measure of national prominence in May 1892, just before that year’s national Republican convention, by issuing a call for a national day of fasting and prayer among African Americans, in a meeting attended by some 1,500 black leaders.

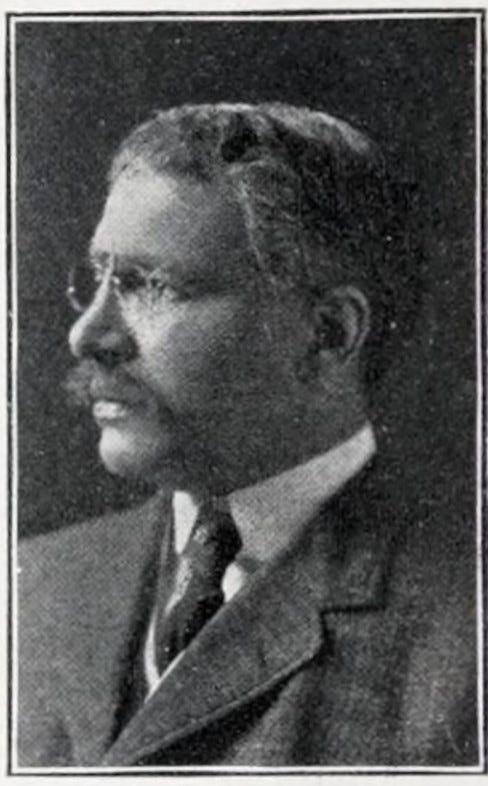

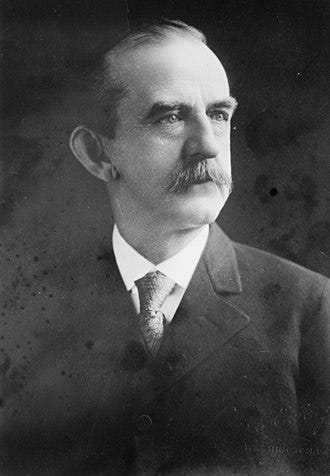

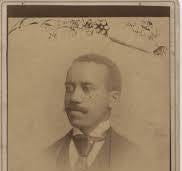

But like many cities in the nation’s new Jim Crow era, Saint Louis was experiencing a significant new phase of racial segregation in housing and society. Some of its major hotels, in fact, refused initially to serve black patrons just before the convention opened, alarming some GOP leaders and angering others. Massachusetts Lt. Gov. W . Murray Crane, state party chairman, reportedly warned the Southern Hotel management that he would withdraw the entire Massachusetts delegation if the hotel refused to accommodate its two black alternates—Dr. Samuel Courtney and former Boston Common Council member Stanley Ruffin—after the hotel balked at first. The hotel backed down.

Dr. Samuel E. Courtney, alternate delegate from Massachusetts in 1896. Public domain photo

Massachusetts delegate W. Murray Crane in 1896. Public domain photo

Most hotels—including the LaClede, Planters’, and Lindell— eventually agreed to honor their reservations, after frantic negotiations by Hotel Committee chairman C. C. Rainwater, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch (“The Black Man Grins Audibly. The Leading Hotels Will Receive Colored Delegates,” June 11, 1896). But the victory was incomplete; at least two delegations with black members—those of Alabama and Mississippi—were refused altogether at the St. James and Mona hotels, in part because of the hotels’ steadfast refusal to open their restaurants to black patrons.

And in the somewhat crazy-quilt world of racial segregation, even hotels which agreed to house and feed official black visitors, free use of the elevators and corridors at the Planters’ was granted only grudgingly. “We will assume [the black visitors} are all politicians for a week,” the management told the Post-Dispatch [“The Negro at the Planters’,” June 11). Black patrons were welcome at the cafe, “and if they insist on eating in the main dining-room, they will be permitted to do so.” At the Laclede, “colored delegates … will be accorded every privilege, and will not be fed in their rooms, but in the dining-room the same as anyone else.”

No verifiable estimate of black visitors to the city in 1896—including delegates, alternates, and unofficial visitors like the members of the Tippecanoe Club of Cleveland, Ohio, an old Whig organization from 1840, reactivated as a bi-racial Republican club in 1888, which apparently sent 500 members, including 150 blacks, to St. Louis—was publicly tallied, but the total probably exceeded 500.

More than 300 black men, including convention delegates, journalists, observers, and influencers, attended a mass meeting on platform language at the city’s First Baptist Church, according to the Post-Dispatch [“Negroes’ Demands. Colored Brothers Demand Planks Against Lynching and in Favor of the Blair Bill,” June 16]. The sponsoring organization was the Executive Committee of the National Republican Association of Colored Men of America.

While many of the men present were from Missouri, just one voting delegate—Perry Carson of Washington, D.C.—was named , along with at least two alternate delegates: Samuel Courtney (Massachusetts) and Jordan Chavis (Illinois). Among those non-delegates listed as present were the nation’s only sitting black congressman, Rep. George Washington Murray of South Carolina, who had recently won a protracted contest to claim his second term in the U. S. House, and James A. Roston of Connecticut, who would later become famous as labor during the Seattle longshoreman’s strike in 1916.

Convention delegates were not identified by race in state lists contained in the official proceedings, so overall numbers are not precise. [Only an unofficial book later compiled by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch attempts to do so, and then only for four states: Florida, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas.] Post-Dispatch coverage of the convention itself (“The Blacks Are for Gold,” June 15, 1896) suggested there were “nearly one hundred [black delegates], almost all from the South.” This article covered proceedings at an unofficial caucus of black delegates convened a day earlier by New York state party boss Thomas Platt, and arranged by two aides: state party treasurer Charles W. Anderson, who was black, and Chris Stewart.

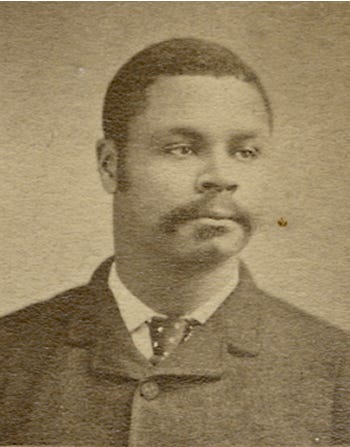

Charles W. Anderson, New York political organizer for Sen. Thomas Platt. Public domain photo

The caucus was intended to measure black support for a “gold plank” in the party’s platform; all but eight delegates supported it, according to the Post-Democrat. The newspaper’s estimate of delegate strength is reasonably accurate, if a little high. My own independent research, based on U.S. census data, newspaper reports, and a variety of other sources has identified at least 75 black delegates from 12 states—including Nebraska, for the first time—and the District of Columbia in attendance at the St. Louis convention in 1896.

That figure sets a new record in my research, at least, along with the identification of at least 70 black alternate delegates from 22 states and the District.

* * * * * * *

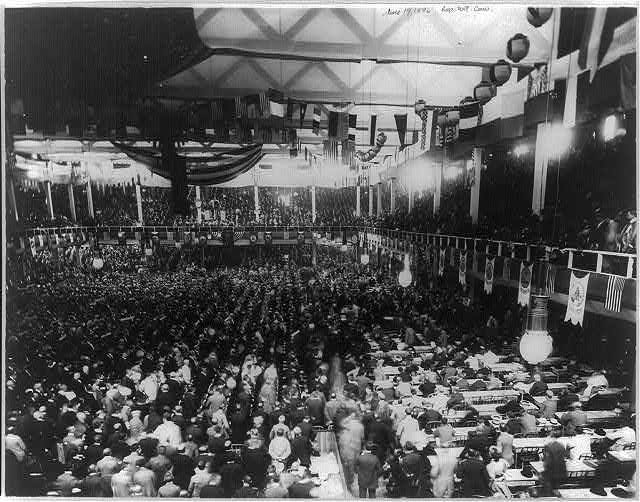

The convention was originally slated to be held in the St. Louis Exposition and Music Hall, but planners determined that repairs and upgrading of the structure could not be carried out in time. So a temporary wooden convention hall, costing $60,000, was instead constructed on the lawn south of the St. Louis City Hall, then under construction.

A deadly tornado had struck the city just a month before the convention, threatening to derail the convention plans, but city leaders persevered, and the new building was dedicated just days before the convention opened. It was then torn down soon afterward, along with the damaged Exposition Hall.

Temporary building housing the 1896 convention at St. Louis. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Black delegates attending the 1896 convention included more than 30 veterans of previous conventions, featuring such well-known veterans as Perry Carson of Washington, D.C.; Herschel Cashin and William J. Stevens of Alabama; Mifflin Gibbs and Ferd Havis (Arkansas); Joseph E. Lee (Florida); John Deveaux, Judson Lyons, Monroe B. Morton, and William A. Pledger (Georgia); Louisiana’s Thomas Cage, Henry Demas, William Harper, Richard Simms, and J. Madison Vance; Mississippi’s George Bowles, Wesley Crayton, and James Hill; North Carolina’s Edward A. Johnson; Richard Allen, Charles M. Ferguson, and Mack M. Rodgers of Texas; and Virginia’s Thomas C. Walker and Alfred W. Harris.

The most experienced delegation by far, however, was South Carolina’s, on which eight black voting delegates had attended previous conventions: William Boykin, William Demos Crum, Edmund Deas, John Fordham, former congressman Robert Smalls, Zacharias Walker, and two longtime postmasters: Charles Wilder of Columbia, and Joshua Wilson of Florence. In addition, at least five of South Carolina’s alternate delegates had also appeared at previous conventions, including former congressman Thomas Miller, some as previous voting delegates.

If many familiar faces were missing—former Senator Blanche K. Bruce and former Congressmen John Roy Lynch of Mississippi and John Mercer Langston of Virginia (retired from politics) and Frederick Douglass, who had died in 1895—there were an ample supply of rising stars, including such new faces as those of North Carolina’s George Henry White, about to be elected to Congress from that state’s Second District; Lemuel C. Livingston, a well-regarded Florida physician; and three emerging Georgia party leaders: alternate delegate Benjamin J. Davis and delegates Henry A. Rucker and Henry Lincoln Johnson, all of Atlanta.

Future congressman George Henry White (R-NC), 1896 delegate. Courtesy

http://www.lib.unc.edu

James B. Raymond, alternate delegate from Pennsylvania in 1896. Public domain photo

George L. Knox, alternate delegate from Indiana in 1896. Public domain photo

Henry Lincoln Johnson, Georgia delegate in 1896. Public domain photo

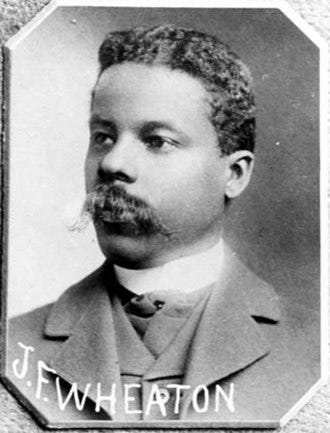

Other newcomers as alternate delegates from non-Southern states included a variety of well-regarded race leaders, such as newspaper publisher George L. Knox of Indianapolis; Rev. Jordan Chavis of Quincy, lllinois; Rev. Paul H. Kennedy of Henderson, Kentucky; J. W. Bolton of Arizona Territory; James B. Raymond of Altoona, Pennsylvania; and lawyer J. Frank Wheaton of Minnesota, who would soon become the first African American member of that state’s legislature.

J. Frank Wheaton, alternate delegate from Minnesota 1896. Courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

Despite the initial difficulties in obtaining housing at the city’s hotels, most of the black delegates generally found St. Louis to be an acceptable site for a brief visit, at least. But at least one black visitor—Texas Freeman newspaper publisher Charles N. Love of Houston, visiting St. Louis to cover the convention—encountered a less pleasant experience, according to local newspaper reports. He was shot and wounded by a man who apparently mistook him for a mugger, after losing his way near his brother’s house at night and inquiring directions (“Colored Delegate Shot,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 13, 1896).

Journalist Charles N. Love, shot in error in St. Louis in 1896. Public domain photo

The newspaper report was inaccurate in one respect—Love was not a delegate, but the Post-Democrat mistook him for an alternate delegate from Texas with a similar name. His wounds were not serious, and he was escorted to his brother’s house, apparently by police who investigated and arrested his assailant.

Next week, I will conclude my look at the 1896 convention by examining actions taken by delegates, including the nomination of William McKinley.

Next time: Getting down to business in St. Louis in 1896