African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 10: Riding a wave of popularity to help lead his party's convention

A half-century later, John Roy Lynch would devote much of a chapter in his autobiography to the 1884 convention and his role in it. In Reminiscences of an Active Life, completed before his death in 1939 but not published until 1970, Lynch retraced the events in typically objective detail, noting that he had not agreed to seek the post until first consulting his good friend from Ohio, William McKinley, with whom he had recently served in the House of Representatives.

McKinley was a stalwart Blaine supporter, but encouraged Lynch to run, regardless. “I know of no man I would rather have them [the anti-Blaine faction] thus honor than you,” McKinley told him, even though he could not vote for him. His longtime friend Mark Hanna, a staunch supporter of Ohio Senator John Sherman, then told Lynch he would win the post by “a majority of about thirty-five [votes]”—a margin which proved to be remarkably accurate, despite the odds against any black candidate.

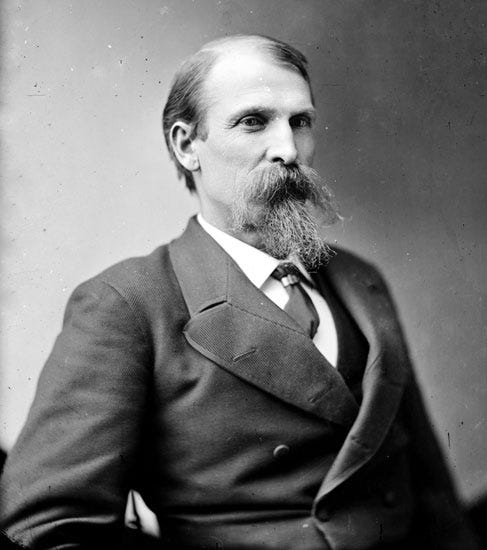

William McKinley as a Congressman from Ohio, ca. 1880. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Theodore Roosevelt, big game hunter, ca. 1885. Public domain photo

But Lynch quickly drew support from many prominent young Republicans, all intent on blocking the ascendancy of early favorite James G. Blaine. Among them were Henry Cabot Lodge, 34, a former member of the Massachusetts legislature, soon to be elected to the U.S. House and eventually to become a veteran Senator, and his good friend and fellow historian Theodore Roosevelt, just 25 and a lowly New York legislator, on his way to becoming President less than two decades later. “Both were intensely opposed to the nomination of Mr. Blaine,” Lynch wrote.

But Lynch, a committed supporter of President Arthur, “did not think I could possibly win,” he wrote. Despite his initial skepticism, he was drafted by the group, persuaded to accept by a committee headed by former Louisiana Gov. Pinckney Pinchback. The argument advanced by McKinley—”this was an opportunity … that comes to a man but once in a lifetime”—was especially poignant.

Pinckney Pinchback, Louisiana delegate in 1884. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Delegate Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, future Congressman and Senator. Public domain photo

It fell to Lodge place Lynch’s name in nomination: “Simply with a view to making a nomination for Temporary Chairman which shall have the best possible effect in strengthening the party throughout the country, there are many members of this Convention, I believe, who feel that a nomination which would strengthen the party more could be made than that which has been presented by the National Committee [Powell Clayton]. I therefore have the honor to move, as it is certainly most desirable that we should recognize, as you have done, Mr. Chairman, the Republicans of the South—I therefore desire to present the name of a gentleman well known throughout the South for his conspicuous parliamentary ability, for his courage and his character. I move you, Mr. Chairman, to substitute the name of the Hon. John R. Lynch, of Mississippi.”

Lodge and Roosevelt were members of an independent reformist faction within the GOP called the “Mugwumps,” who opposed corruption and were memorably skeptical of Blaine’s past record. The entire convention recognized their sudden opposition as a warning to Clayton and other Blaine supporters that he did not yet have the nomination sewed up. If Lodge denied that his nomination of Lynch was intended as a “test vote as to the strength of candidates,” it was clearly a shot across the bow of the Blaine campaign.

Minutes later, Roosevelt rose to endorse the Lynch nomination by invoking the party’s martyred President: “It is now, Mr. Chairman, less than a quarter of a century since, in this city, the great Republican party for the first time organized for victory, and nominated Abraham Lincoln, of Illinois, who broke the fetters of the slave and rent them asunder forever. It is a fitting thing for us to choose to preside over this Convention one of that race whose right to sit within these walls is due to the blood and the treasure so lavishly spent by the founders of the Republican party. And it is but a further vindication of the principles for which the Republican party so long struggled.”

Delegate Powell Clayton (1833-1914) of Arkansas, ca. 1875. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Clayton, a former Union general from Pennsylvania who became controversial Reconstruction-era governor and U.S. Senator from Arkansas, served on the Republican National Committee from his adopted state for two decades. Widely respected, he had been the national committee’s overwhelming choice before Lynch was nominated. Powell’s only negative credential appeared to be favoring Blaine for president—one of the few Southern state leaders who openly did so in 1884.

That Lynch was able to defeat him by 40 votes in a roll-call vote—the only one in which individual delegates’ names were actually listed—was a momentary shock to the Blaine campaign. But even so, the black vote was not monolithic. Of the 68 black delegates who did cast votes, only 56 of them actually voted for Lynch. In all, 12 black delegates, including Lynch, voluntarily chose Clayton, including all four delegates from Arkansas (Mifflin Gibbs, Ferd Havis, Samuel Holland, and John Johnson); three of five from Texas (Norris Cuney, Robert Evans, and Henry Ferguson); two of eight from Louisiana (Robert Guichard and William Harper); and one each from the District of Columbia (Perry Carson) and North Carolina (John Williamson, one of six).

Only Lynch explained his reason: reciprocity. The Arkansas delegates, of course, were demonstrating state loyalty to Clayton, their delegation chairman, although how many of them eventually voted for Clayton’s preferred nominee—James G. Blaine—cannot be determined. The rest of the 12 may have favored Blaine, although almost all black Southern delegates voted for Arthur on the first three ballots, at least—Southern delegates as a whole favored Arthur by about 3 to 1 from the outset.

Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia delegations, with 47 black delegates between them, gave only eight to Blaine on the first ballot, slowly increasing to 12 on the third ballot and 27 on the fourth and final. The other Southern delegations, with 21 black delegates, were either split or generally favored Blaine, giving him 45 votes on the first ballot.

Lynch downplayed the personal importance of his victory in his first address as temporary chairman: “I feel that I ought not to say that I thank you for the distinguished honor which you have conferred upon me, for I do not. Nevertheless, from a standpoint that no patriot should fail to respond to his country's call, and that no loyal member of his party should fail to comply with the demands of his party, I yield with reluctance to your decision, and assume the duties of the position to which you have assigned me.

”Every member of this Convention who approached me upon this subject within the last few hours, knows that this position was neither expected nor desired by me.

If, therefore, there is any such thing as a man having honors thrust upon him, you have an exemplification of it in this instance. I wish to say, gentlemen, that I came to this Convention, not so much for the purpose of securing the defeat of any man, or the success of any man, as for the purpose of contributing to the extent of my vote and my influence to make Republican success in November next an assured fact. …

I wish to say, so far as the different candidates for the Presidential nomination are concerned, that I do not wish any gentleman to feel that my election by your votes is indicative of anything relative to the preference of one candidate over another.

I am prepared, and I hope that every member of this Convention is prepared, to return to his home with an unmistakable determination to give the candidates of this Convention a loyal and hearty support, whoever they may be. … when we go before the people of this country, our action will be ratified, because the great part of the American people will never consent for any political party to gain the ascendency in this government, whose chief reliance for that support is a fraudulent ballot and violence at the polls.

I am satisfied that the people of this country are too loyal ever to allow a man to be inaugurated President of'the United States, whose title to the position may be brought forth in fraud, and whose garments may be saturated with the innocent blood of hundreds of his countrymen. .. the American people will … never consent to a revenue system in this government, otherwise than that which will not only raise the necessary revenue for its support, but will also be sufficient to protect every American citizen in his occupation. Gentlemen, not for myself, but in obedience to custom, I thank you for the honor you have conferred upon me.

John Roy Lynch (1847-1939), temporary chairman of 1884 convention. Photo courtesy Mississippi Civil Rights Museum

Lynch was among 15 Southern black delegates named to important posts by the convention, including North Carolina’s Rep. James O’Hara, the only black named to the influential Credentials Committee. Another seven black delegates were named to the Committee of Permanent Organization, while four each were named to the Resolutions and Rules Committees. Black delegates from five states—Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Texas—and the District of Columbia were named as state vice presidents, while black delegates from Florida, South Carolina, and Texas became assistant secretaries for their states.

The special committee appointed to present their nominations to James G. Blaine in Maine and Henry A. Logan in Washington, D.C., included four black delegates: William G. Stewart of Florida, Samuel Lee of South Carolina, Norris W. Cuney of Texas, and Perry Carson of the District of Columbia.

* * * * * * * *

As detailed in last week’s entry, Blaine won the nomination on the fourth ballot, if still without the overwhelming support of black delegates, most of whom had held out for President Arthur’s renomination—in part, because of misgivings over Blaine. His nomination struck a somewhat unwelcome new precedent, as the first postwar Republican nominee who had not served as a Union officer during the Civil War.

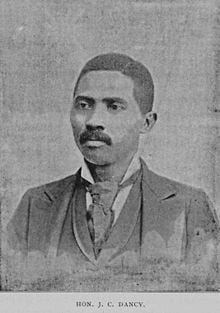

For some black leaders, at least, the choice of John A. Logan as vice presidential nominee seemed to counterbalance Blaine, setting some of their fears at rest. The immensely popular Senator had a gallant war record, and had served as third commander in chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, the postwar veterans organization. North Carolina’s delegate John C. Dancy made that very subtle point in remarks just before Logan’s nomination was approved by acclamation.

North Carolina GOP delegate John C. Dancy, shown in 1895. Public domain photo

Speaking as “the humble representative of twelve hundred thousand colored voters in this country,” Dancy predicted that the addition of Logan would significantly enhance the ticket’s chances in North Carolina, at least and other Southern states. “[Y]ou will strengthen the confidence and courage of these twelve hundred thousand colored voters; and each and every one of them on the day of the election will be found at the polls casting their votes for those two candidates. Gentlemen, we know John A. Logan in the South; we have learned to love him and to honor him.

“He has stood by us under any and all circumstances. We will be certain to stand by him. Great in war, he has been likewise great in peace; and, keeping the even tenor of his way, he has won the confidence and respect, not only of the Republican party, but of the Democratic party as well; and I believe that he can command as many votes in the South as any man who could be named; and as we have a State that was Democratic by only 300 two years ago, we know that with this ticket we can carry it by at least 5,000 majority in this election. And so speaking for North Carolina, I say for it, as I say also for some others of the Southern States, we are for John A. Logan, first, last, and all the time.”

Dancy’s optimistic prediction, alas, did not come true in the fall election. Instead, Democrat Grover Cleveland and running mate Thomas Hendricks carried the state handily, by more than 25,000 votes—ironically, almost half of the slim national margin in popular votes—along with every other Southern state and most of the East. Even had they managed to carry North Carolina, however, Blaine and Logan would still have lost the electoral college, after Cleveland’s home state of New York provided victory by one of the narrowest margins in history, just over 1,100 votes—making him the first Democrat to win the presidency in three decades.

* * * * * * * *

While in Chicago, the black Republican delegates were welcomed by the city’s small but significant black population, which more than doubled during the 1880s, from 6,500 in the 1880 U.S. census (about 1.2 percent of the 500,000 total) to more than 15,000 a decade later. Black Chicagoans were already beginning to boast social clubs rivaling those of prosperous white society, including the “Les Enfants” club for younger citizens.

So it was that delegates to the 1884 convention were entertained on Friday night, June 6, at a festive musical program sponsored by Les Enfants at the city’s Weber Music Hall, located just blocks from the Exposition Center site of the convention. According to the Chicago Inter-Ocean report of June 7, 1884 (“Entertaining Colored Delegates”), the crowd on hand—”in full evening dress”— numbered some 200, limited to club members, their guests, and all invited black delegates in the 400-seat hall, where “a well-arranged musical and literary programme was creditably rendered, after which refreshments were served and dancing indulged in until a late hour.”

Chicago’s Weber Music Hall, ca. 1878, where black delegates were entertained in 1884. Illustration courtesy www.chicagology.com

Delegates in attendance were not named, but almost certainly included the party’s leaders—John Lynch, John Dancy, Blanche Bruce, and Pinckney Pinchback, and others—and may well have included dozens of alternate delegates who had come to Chicago, and had not yer left the city.

Whether that included William H. Outlaw, an black alternate delegate from North Carolina’s Bertie County—employed as a mid-level clerk in the War Department’s Medical Department in Washington, D.C., who had attended at least some of the proceedings—is not known. The delegate for whom he served as backstop—John Dancy, whose speech endorsing Logan appeared earlier in this entry—was present and active. However he came to have extra tickets to the convention, Outlaw decided to sell them to the highest bidder, and according to the Washington Evening Star, utilized a local broker named D. D. Dawson.

The Evening Star did not connect all the dots when it picked up the story for its front-page convention coverage of June 4, 1884. Its correspondent did not seem to know that Outlaw was an official alternate delegate, only that he had somehow “come into possession of a couple of tickets to the convention.” He reportedly met Dawson soon after arriving in Chicago on June 1, and arranged for Dawson to scalp the tickets, after “considering that his expenses warranted their disposal."

According to the Evening Star, after “failing to see anything of his broker, Outlaw had him arrested last night [June 3] by Officer Smith and booked for swindling.The tickets were found on Dawson, who claimed he had not yet found a purchaser. Tickets are selling to-day for $75.”

That was only one version of the story, a somewhat fuller version of which appeared in the Chicago Inter-Ocean three days later:

W. H. Outlaw, the colored delegate from the District of Columbia, who caused the arrest of D. D. Dawson, to whom he gave a convention ticket to sell, claims the whole affair has been misrepresented. He states that a Mr. Cole, an acquaintance, requested him to preserve a ticket for him, and that in compliance with this he purchased one from George Williams, of Washington, for $20. Cole failed to turn up, and not wishing to lose the amount, he gave the ticket to Dawson to dispose of. He was informed that the latter intended to beat him of the amount and complained to the police, which led to the arrest. Mr. Outlaw fully exonerates Dawson of any intent to defraud him of the ticket or the amount realized from its sale.

Whichever version was true, irreparable damage was done to Outlaw’s political reputation by the minor scandal, and his services were no longer needed by the party after 1884, at least in North Carolina. Although he continued to work as a clerk in Washington for anther 20 years, for unspecified agencies, his availability after 1884 went unnoticed, discredited by the embarrassing reports of his unsuccessful adventure in Chicago.

Outlaw may have continued for a while to work as a federal employee, but his days were probably numbered, even without the scandal. The new Democratic administration certainly had no interest in providing patronage appointments to Southern Republicans, or in reappointing its previous jobholders. Although Republicans maintained control of the U.S. Senate, Cleveland’s Democrats kept control of the U.S. House throughout his first term. Worse for blacks, the two sitting Congressmen—Smalls and O’Hara—from the Carolina would lose their seats in 1886, after being reelected in 1884, leaving the House devoid of black leadership.

After 24 years of comparative success in obtaining those appointments, both in Washington and in the field, black applicants especially saw the pool of available jobs begin to dry up almost immediately. There was only one solution: work to restore Republicans to the White House in 1888. And their work began in earnest in the spring of 1885, when President Arthur left the White House.

At least 21 of the black delegates and alternates from 1884 would return in 1888, including Lynch and at least 20 veterans from 1884. Dancy and his North Carolina colleagues, James Harris and John Williamson, were among those selected to return, along with such veterans as South Carolina’s Robert Smalls and state party leader Edmund Deas; Tennessee’s Samuel McElwee; Norris Cuney, Richard Allen, and Henry Ferguson of Texas; and Virginia’s Alfred W. Harris.

But the national leadership of the GOP was entering a period of major potential changes, with the deaths in 1886 of both former President Arthur and vice presidential nominee John A. Logan. Blaine would remain a sentimental favorite to many as the next election approached, although Senator John Sherman would show new popular strength. Both the future seemed to belong more to the likes of Henry Cabot Lodge and Theodore Roosevelt, the young reformers who had agree, somewhat reluctantly, to support Blaine.

Only time would tell how the ongoing changes in national leadership might affect the opportunities afforded black Republicans.

Next time: Back to work in 1888, as Republicans seek to unseat Grover Cleveland