African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 3: Some African American soldiers vote in the field in the 1864 election

The actual number of African Americans who voted in the 1864 presidential election will never be known, but likely fewer than 10,000—with just six Northern states (and possibly, Ohio) allowing black Americans to register and vote before passage of the Reconstruction amendments to the U.S. Constitution. But some of those were a distinctive group of free black men—Union soldiers—whose votes were often cast in the field of battle as the Civil War drew, inexorably, to its close.

I came across mentions of this seeming anomaly while conducting research for my current book project, dealing with black Republican delegates to the Republican national conventions between 1868 and 1904. As part of my research for a planned introduction, I was first fascinated to read about the Port Royal experiment, which produced the only known black delegates—a handful of black Union soldiers from the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops regiment stationed there—to attend the 1864 National Union party convention in Baltimore.

I wrote about their presence in my previous two blog entries here, along with their unsuccessful attempt to be seated as voting delegates there. Yet even had they prevailed at the convention, none of those black South Carolina delegates could have voted in the fall election, hailing as they did from Southern states still at war with the Union, where blacks would not gain the right to vote until well after the end of the war.

With a few exceptions, almost all of the 33rd USCT troops were self-emancipated slaves from Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina—although some free blacks from Northern states may have enlisted in its ranks. Only six U.S. states allowed full voting rights by eligible black males at the time, concentrated in the northeast: Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont, and reportedly joined by Ohio in the Midwest.

New York, with the nation’s largest population of free blacks (49,000) in the 1860 census, restricted suffrage somewhat to black men owning at least $250 worth of property. Meanwhile, Ohiohad reportedly allowed some of its 37,000 free blacks (in 1860) to vote, but had curiously restricted its suffrage with a non-economic qualification—men of color who were demonstrably “more white than black”—apparently by forcing applicants to prove the proportion of their racial mixture to their local registrars.

According to public historian Tim Talbott, “It appears that decisions on who was ‘more White than Black’ came from local election officials. Those [Ohio] townships who saw the value of accepting votes from men of African descent allowed it, while others did not.” [See “‘ That had earned him the right to vote,’” by Tim Talbott, 2022, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2022/11/03/that-had-earned-him-the-right-to-vote-anywhere-black-soldiers-vote-in-the-1864-presidential-election/ .]

The historical situation in Ohio is more than a little confusing; an 1859 law banning black suffrage was challenged in court and reportedly overturned, according to one historian, Van Gosse. Full voting rights for blacks were rejected after the War in a statewide referendum, and not implemented until the adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution (1870).

Altogether, the seven states sent at least 15,000 black volunteers into their state volunteer regiments and into the more than 140 U.S. Colored Troops regiments created in 1863 and 1864, some of them repurposed state regiments, such as Ohio’s 127th state infantry (renamed Fifth U.S. Colored Troops regiment).

Theoretically, most of those 15,000 black soldiers should have been able to vote in the fall of 1864 by absentee ballot, as suggested by Congress in 1863—urging states to allow it for the military in U.S. history—provided they were 21 years old and registered in their home states. Almost all Union states took that to heart, although some still required soldiers to return home to vote rather than submit absentee ballots. (Prior to 1864, active-duty military stationed outside their home states were not allowed to vote at all.)

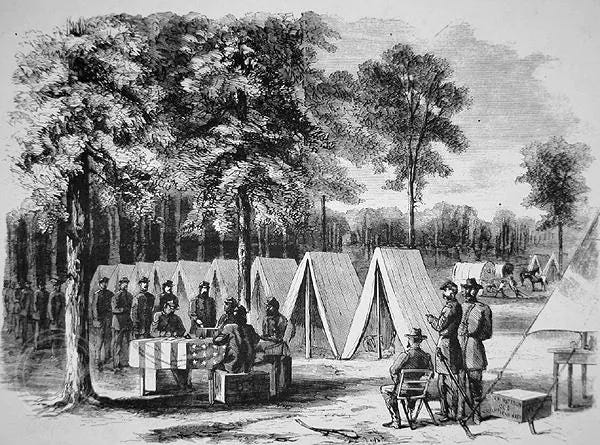

Pennsylvania soldiers voting at Army of the James headquarters, September 1864, from Harpers Weekly, 29 October 1864. Courtesy of Library of Congress

According to the American Battlefield Trust, states like Pennsylvania allowed military registrants to vote in their camps, by absentee ballot. Famous Civil War artist Alfred Waud captured the scene of Pennsylvania voters in the headquarters of the Army of the James, near Bermuda Hundred, Virginia, in September 1864—more than a month before the election occurred—for a late October edition of Harper’s Weekly magazine.

But for northern states which did not allow absentee voting, “provisions were often made for soldiers to be sent home for furloughs to vote in their hometowns during the autumn months.

Election officials made extra efforts to ensure the honesty of the election, and most voting soldiers also took their vote and method of casting a ballot seriously.

Voting in the 1860s did not include secret ballots, so whether voters cast their ballots in their hometowns or in a military camp, their votes were not secret. Voting was seen as a community and civic event, and the “community” of soldiers in military camps during the Civil War became a key voting bloc in the 1864 Election.”

In the end, a total of 40,247 Union soldiers voted—30,503 of them for Lincoln, 75.8 percent, with about a quarter of their votes cast for General George McClellan, his Democratic opponent. [See “The Election of 1864 and the Soldiers’ Vote,” American Battlefield Trust, 2024, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/election-1864-and-soldiers-vote .]

* * * * * * *

Sadly, a number of dedicated black soldiers—fighting valiantly for the rights of black men, racial cousins most would never meet—were killed before they could exercise their own right to vote in 1864. More than 250 of those heroes were in the Massachusetts 54th, among the most famous of all black units in Civil War history (subject of the acclaimed motion picture Glory, starring Denzel Washington and Matthew Broderick). Many of them were interred initially in a mass grave near Fort Wagner, outside Charleston, S. C., killed in a bloody battle there in July 1863.

In one of history’s supreme ironies, those dead men from Massachusetts had earlier crossed paths for a few weeks in June 1863 with their South Carolina counterparts in the 33rd USCT, while stationed briefly at Beaufort a month before their famous battle in July. Many of the wounded would return to Beaufort for treatment the following week, where at least a dozen of them would die of their injuries or disease.

In late June, however, the mood was festive on their arrival. According to the National Park Service website, “The regiment paraded through the streets of Beaufort, where onlookers included soldiers in the 1st and 2nd South Carolina Volunteers, two all-Black regiments organized in the Sea Islands the previous year. Officers freely mingled with teachers, including Charlotte Forten at the Penn School,” who was especially fond of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw—and later mourned his death while helping nurse the survivors of his regiment. [See The Journal of Charlotte Forten, pp. 191-196.]

Shaw and most of the dead men from the 54th—perhaps as many as 200 in all—lay buried for the moment in a huge trench near Fort Wagner, ordered as a final insult by victorious Confederates—and later exhumed and removed to unmarked graves at Beaufort. Another 60 or more of their wounded colleagues would be evacuated to the hospitals at Beaufort to recover after the tragic battle, in which more than 1,000 Union soldiers died in all—including the 54th regiment’s white commander, Colonel Shaw (1837-1863).

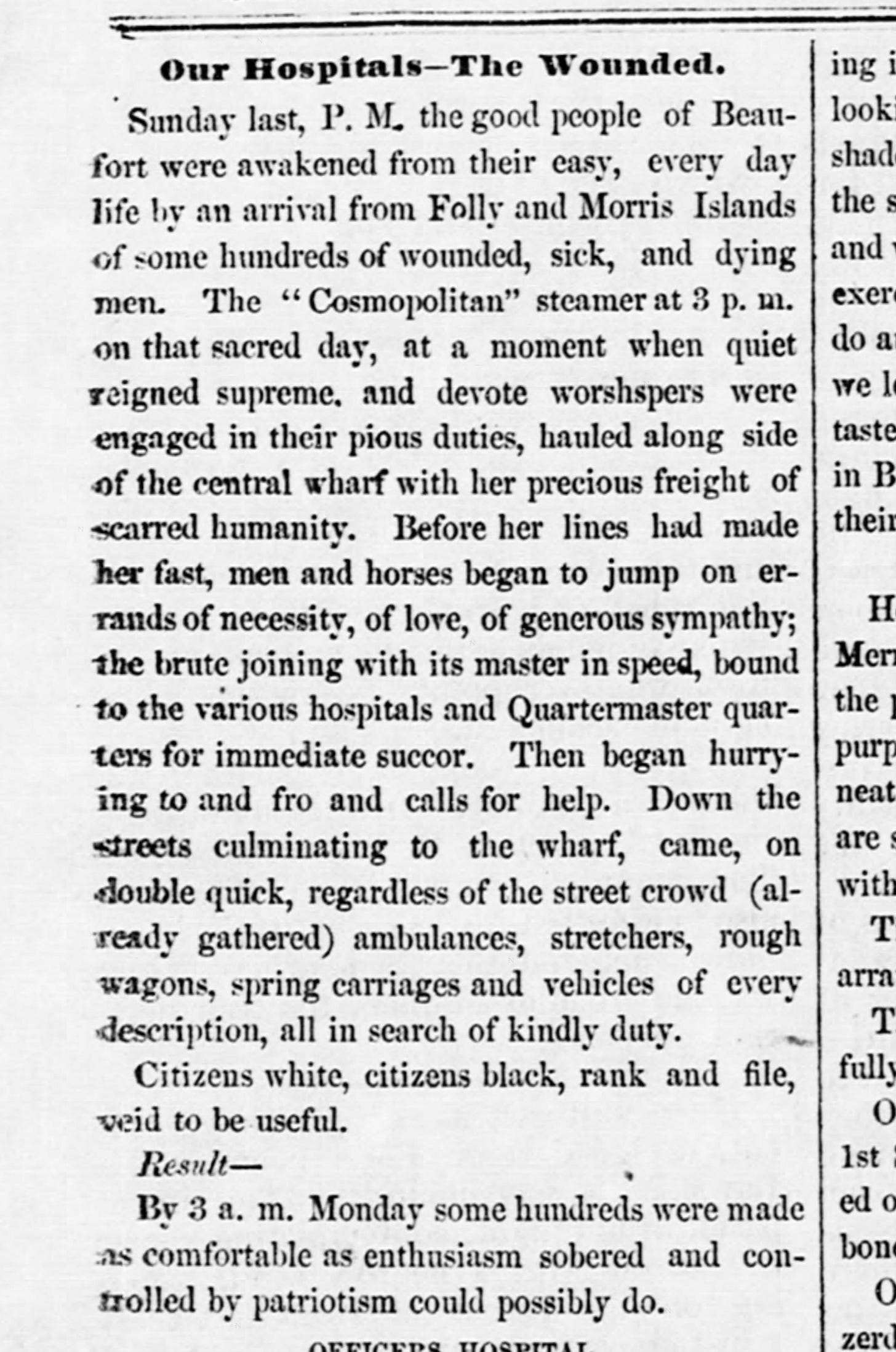

Depiction of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry regiment storming Fort Wagner in July 1863. Courtesy Library of Congress

The Beaufort Free South recorded the frantic arrival of the “hundred of wounded, sick, and dying” Fort Wagner survivors in an article published just days after the battle.

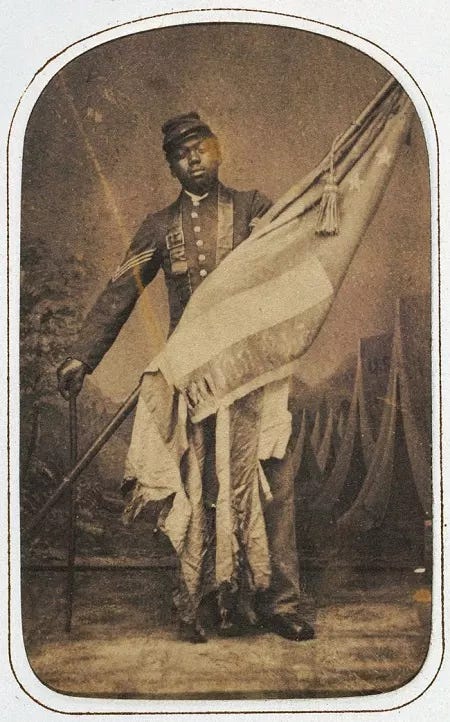

The incoming wounded filled six of Beaufort’s military hospitals to capacity, with at least 60 of the 54th Massachusetts men filling one on their own (Hospital No. 6, called “The Castle”). One of those wounded—who later received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his valor, belatedly in 1900—was Private (later Sgt.) William H. Carney (1840-1908), who “retrieved the American flag and continued to march it forward “pressing his wound with one hand and with the other holding up the emblem of freedom,” according to the National Park Service biographical sketch.

Despite multiple serious wounds, Carney pushed forward and planted the flag upon the parapet. When Union forces had to retreat Carney continued to carry the flag until he made it to friendly lines and handed it to another member of the 54th Massachusetts. Upon arriving at federal lines Carney cried, “Boys, I did but my duty; the dear old flag never touched the ground!”

[See “William H. Carney,” https://www.nps.gov/articles/william-h-carney.htm .]

Sgt. William H. Carney, 54th Massachusetts regiment hero. Courtesy Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Carney, born to enslaved parents in Norfolk, Virginia, and secretly educated by a white minister, had escaped to freedom in Boston on the Underground Railroad in the last years before the Civil War. He enlisted in the Morgan Guards in February 1863, a smaller unit later absorbed into the Massachusetts 54th regiment. Carney’s lengthy recovery from serious wounds sustained at Fort Wagner led to his early medical discharge from the Army and his return home in mid-1864.

“The Castle,” Beaufort’s Hospital No. 6, where Carney was treated, as it appears today. Courtesy Kevin Levin

But most of the survivors of the Fort Wagner battle lived on to fight another day—and perhaps even to vote in the field, before the regiment was mustered out in 1865. A dozen or more of the 54th’s wounded evacuees, however, never left Port Royal, succumbing instead to injuries or disease. They are buried in Section 16 of the Beaufort National Cemetery, a silent tribute to their continuing courage.

Gravestones at the Beaufort National Cemetery. Courtesy National Park Service

* * * * * * *

How many of the Massachusetts 54th survivors were able to vote in the field in 1864 may never be known. Only about one-seventh of the regiment were actually from Massachusetts, as it turns out—and thus eligible to vote there. (The rest were from Pennsylvania and other Northern states.) Sergeant Carney, having returned home, was at least eligible to vote in person at New Bedford, Massachusetts.

But for other African American soldiers, especially those from Ohio, the right to vote in person by absentee ballot was observed scrupulously. In 1863, Ohio had passed a law specifically allowing absentee soldier voting. Among those soldiers were Black troops of the 5th United States Colored Troops (USCT), whose mixed racial makeup made them eligible to vote in Ohio’s elections.

As recounted by the National Park Service, “Thirty-nine days after capturing Fort Harrison [Virginia] on November 8, 1864, they cast 194 votes for Abraham Lincoln. These are the first known Black soldier votes in Virginia, and likely the entire South.” Fort Harrison was located just outside Richmond, the Confederate capital. [See https://www.nps.gov/planyourvisit/event-details.htm?id=36116EA4-D600-6536-7A2E11C9E7255800 .]

Other black soldiers—including those from New York—also took advantage of a wartime law that allowed soldiers to vote while in the field, regardless of their race. Oyster Bay town historian John E. Hammond documented the case of town resident Wait Mitchell, who fought with the 26th USCT regiment, raised at Riker’s Island in February 1864 and posted to Port Royal two months later.

According to Hammond, “a soldier could cast his vote by absentee ballot by completing a form called ‘Soldier’s Power of Attorney,’ which would then be signed by his commanding officer and sent to the soldier’s local voting district.

Mitchell filed an affidavit, now in the town archives, with Justice of the Peace John Rushmore that authorized the official to vote on his behalf in the Nov. 8, 1864, general election. According to Hammond, included in the envelope with the form was a “small piece of paper with the name Horace Greeley printed on it, indicating the voting preference of Wait Mitchell.

Greeley was a New York elector for President Abraham Lincoln. [See “Black Civil War Soldiers,” by Bill Bleyer, at https://www.molloy.edu/news/black-civil-war-soldiers-often-overlooked-by-history-gaining-more-recognition .]

How many more of the 4,125 black New Yorkers fighting for the Union followed Wait’s lead is not known with any certainty. The 26th USCT, posted to Port Royal in April 1864, remained there until mustered out in August 1865, when more than 140 of its enlisted men had died of injuries or disease.

Across the entire realm of U.S. Colored Troops, casualties from battle were relatively small—only about 3,000 of the more than 180,000 black troops who served were killed in battle or died from injuries received. But roughly 35,000 other black troops died from disease and other causes—including summary execution as Confederate prisoners of war; nearly half of all black prisoners died in Confederate captivity, according to some reports, including an estimated 300 black troops shot after surrendering at Fort Pillow, Tennessee in 1864.

* * * * * * *

Perhaps the most poignant moment of all for the men of the 33rd USCT regiment occurred on February 9, 1866, when the regiment was officially being mustered out on Morris Island, near the battle site of Fort Wagner, in Charleston Bay. Col. Charles T. Trowbridge, who had taken over command of the 33rd after the departure of Col. Higginson nearly two years earlier, delivered this mustering-out message to the soldiers:

“The hour is at hand when we must separate forever, and nothing can take from us the pride we feel, when we look upon the history of the ‘First South Carolina Volunteers,’ the first black regiment that ever bore arms for defense of freedom on the continent of America …

On the 9th day of May, 1862, at which time there were nearly four millions of your race in bondage, sanctioned by the laws of the land and protected by our flag,—on that day, in the face of the floods of prejudice that well-nigh deluged every avenue to manhood and true liberty, you came forth to do battle for your country and kindred.

And from that little band of hopeful, trusting, and brave men who gathered at Camp Saxton on Port Royal Island … has grown an army of a hundred and forty thousand black soldiers, whose valor and heroism has won for your race a name which will live as long as the undying pages of history shall endure …

It was a bittersweet moment for the men of the 33rd, who stood near the mass grave of their valiant friends from the 54th Massachusetts, as Trowbridge further noted:

“It seems fitting to me that the last hours of your existence as a regiment should be passed amidst the unmarked graves of your comrades, at Fort Wagner. Near you rest the bones of Colonel Shaw, killed by an enemy’s hand in the same grave with his black soldiers who fell at his side; in the future your children’s children will come on pilgrimages to do homage to the ashes of those who fell in this glorious struggle.

The church, the school-house, and the right forever to be free are now secured to you, and every prospect before you is full of hope and encouragement. This nation guarantees to you full protection and justice, and will require from you in return that respect for the laws and orderly deportment which will prove to everyone your right to all the privileges of freedmen.

[For the full text, see Susie King Taylor’s Reminiscences of My Life in Camp, pp. 46-49, available at https://www.google.com/books/edition/Reminiscences_of_My_Life_in_Camp_with_th/v3-cyYKvZr8C?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PP13&printsec=frontcover .]

Boston’s Robert Gould Shaw memorial. Public domain photo

Those “privileges of freedmen,” of course, would include the right to vote—which was still being denied to free blacks across the South—but would finally become available to these South Carolinians, including Prince Rivers and Henry Hayne, and their comrades in early 1868.

Next time: A change of pace: thoughts on U.S. domestic politics