African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 4: Three spirited speeches set the pace for the future of black Republicans

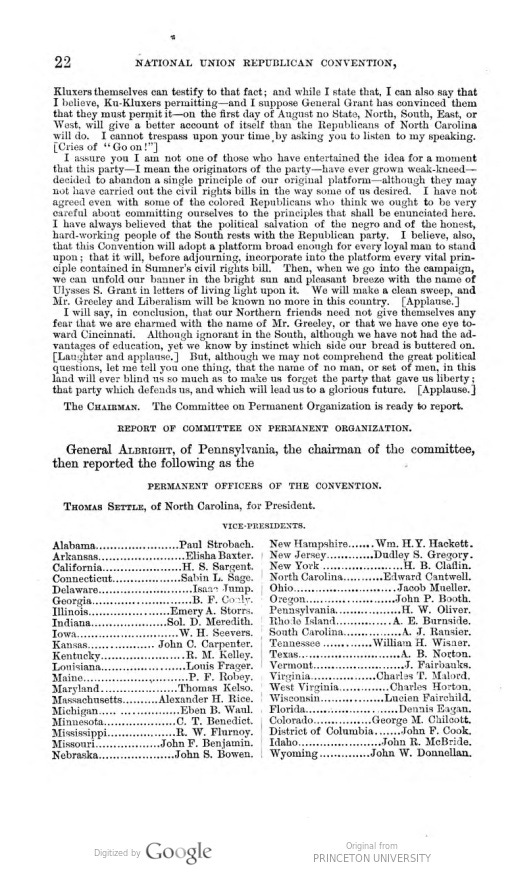

Last time, I introduced readers to the setting of the 1872 Republican national convention in Philadelphia, where a record number of African American delegates sought to help renominate President Ulysses S. Grant, hero from the Civil War. This current series is part of my planned book on early black Republicans between 1868 and 1920, based on my still-continuing research.

More than 100 black delegates and alternates were named to attend the convention, representing 15 states and the District of Columbia, in just their second national outing since gaining citizenship. Among them were four memorable speakers, the first black men ever to address a national convention.

The first to speak in June 1872 was William H. Grey of Arkansas, a 43-year-old minister and state legislator whose elegant remarks were described in my last posting. This time, I focus on addresses by three younger delegates, representing three other Southern states—Mississippi, South Carolina, and North Carolina—who personified the present and future of a rising wave of influential black leaders in the party.

Robert Brown Elliott, youngest of the four, was not yet 30 years of age, but had already represented South Carolina in Congress for more than a year since taking office in March 1871, after his election in November 1870. Believed to have been born in England of unnamed West Indian parents, and reportedly educated at Eton, Elliott has been described as the “first full-blooded man of color” elected to Congress. (His congressional colleague Joseph Hayne Rainey, reportedly of mixed race, took office in November 1870.) [See Elliott’s biographical sketch at https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/elliott-robert-brown/ ].

A practicing lawyer and active journalist, Elliott had moved from Boston to South Carolina in early 1867, after the war, but had already acquired a rather enviable reputation in just five short years—first at the state’s constitutional convention, then in the state legislature—as a vigorous and intellectual speaker and writer. His brief remarks here were delivered on behalf of “the nine hundred thousand voters of our race, whose convictions are like unto your own. … we intend to use the rights that have been given to us, to use the elective franchise, in the interest of the country, the interests of the American people. …

“We [ask] only what is just and fair, performing what is right, we mean to contribute our fair share and our full quota toward making our country what we conceive, along with you, it ought to be: a country that guarantees to all its citizens the equal protection of the law.”

The full text of his remarks follows below:

After delivering this brief convention speech, Elliott would go on to give one of the most impassioned speeches ever delivered in the U.S. House, offered in support of the 1875 Civil Right Act, just before resigning his seat in November 1874.

The speaker who next appeared, delegate James H. Harris of North Carolina (1832-1891), who had been offered a similar opportunity four years earlier, as an alternate delegate, but was not to be found on the floor during that brief window.

Already a veteran of the North Carolina General Assembly, after serving as a delegate to his state’s 1868 constitutional convention, Harris was currently campaigning for a seat in the state Senate, having recently lost his first bid for Congress. Among the most versatile of the state’s early black political leaders, he had lived in Ohio before and during the Civil War, then recruiting black soldiers in Indiana. He also traveled abroad—to Canada, Sierra Leone, and Liberia—before returning to North Carolina in 1865 to teach and help establish the Union League.

Harris was ambitious, but not foolishly so; he had once reportedly turned down President Andrew Johnson’s appointment as U.S. Minister to Haiti, following the 1867 death of Minister Henry Everard Peck in Port-au-Prince.

His remarks were brief, yet cleverly pointed. Harris drew enthusiastic applause by firmly aligning himself with the mainstream Republican party: “I have always believed that the political salvation of the Negro and of the honest, hard-working people of the South rests with the Republican party,” but encouraged the platform drafters to include “every vital principle contained in [Senator Charles] Sumner’s civil rights bill … the name of no man, or set of men, in this land will ever blind us so much as much as to make us forget the party that gave us liberty.”

Harris’s reference to Reform Republican nominee Horace Greeley—also favored by the Democratic Party, which offered no nominee of its own that year, in a daring action that turned out disastrously—seemed curious. It was a veiled warning to fellow black voters not to be “charmed” into voting for Greeley, despite his fervent support for black political equality. In that year’s complicated political dance, Democrats endorsed Greeley but refused to endorse the Sumner civil rights bill, now languishing in the Senate. (Sumner, of course, had angered Grant by refusing to endorse the administration’s annexation treaty for Santo Domingo, among other controversial actions, and had accordingly been all but drummed out of the true Republican Party.)

* * * * *

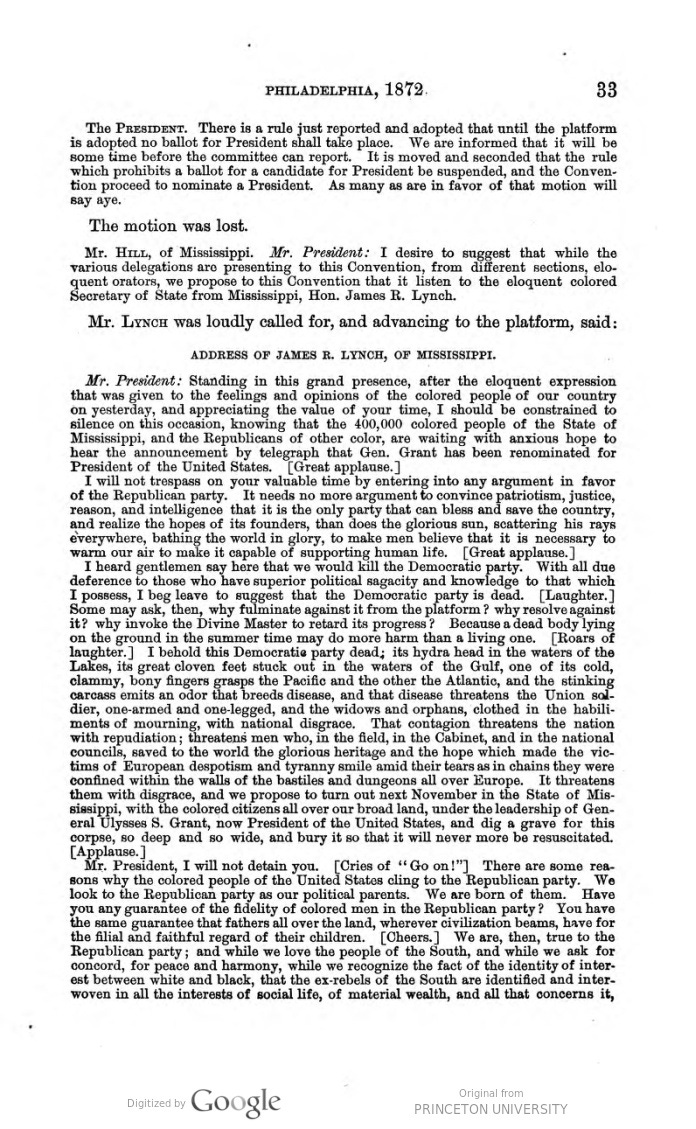

The next day, convention delegates were treated to an astounding speech by Mississippi’s Secretary of State, James D. Lynch, an AME minister whose energetic and elegant speaking style belied both his youth—just 33—and his soon-accelerating physical decline. As chairman of the Mississippi delegation, he offered both substance and an inimitable style.

He listed the “reasons why the colored people of the United States cling to the Republican party … the only party that can bless and save the country, and realize the hope of its founders.” The “Democratic Party is dead,” he declared, and “the 400,000 colored people of the state of Mississippi … propose to turn out next November in the State of Mississippi … with the colored citizens all over our broad land … and dig a grave for this corpse, so deep and so wide, and bury it, so that it will never more be resuscitated.”

Mississippi’s black voters “look to the Republican party as our political parents. We are born of them,” Lynch told his listeners, who interrupted him frequently with loud applause. Grant, once renominated, “would be a strong candidate at the South … ”

Like a thundering pastor exhorting his congregation to go out and do the work of the Lord, Lynch said he would tell Southerners to “let the light of this great candle of liberty … burn” by keeping Grant as the nation’s leader. “That man who had the genius to command your armies when the nation was incredulous of success; who could stand reverse; … understands the wants of this great country.”

In its front-page coverage the next day (June 7), the New York Times printed the full text of Lynch’s remarks. His full text, as presented in the convention Proceedings, can be enjoyed below.

* * * * * *

Despite their enthusiastic receptions, none of the four speakers in 1872 were destined to prosper significantly from their time in the convention’s limelight.

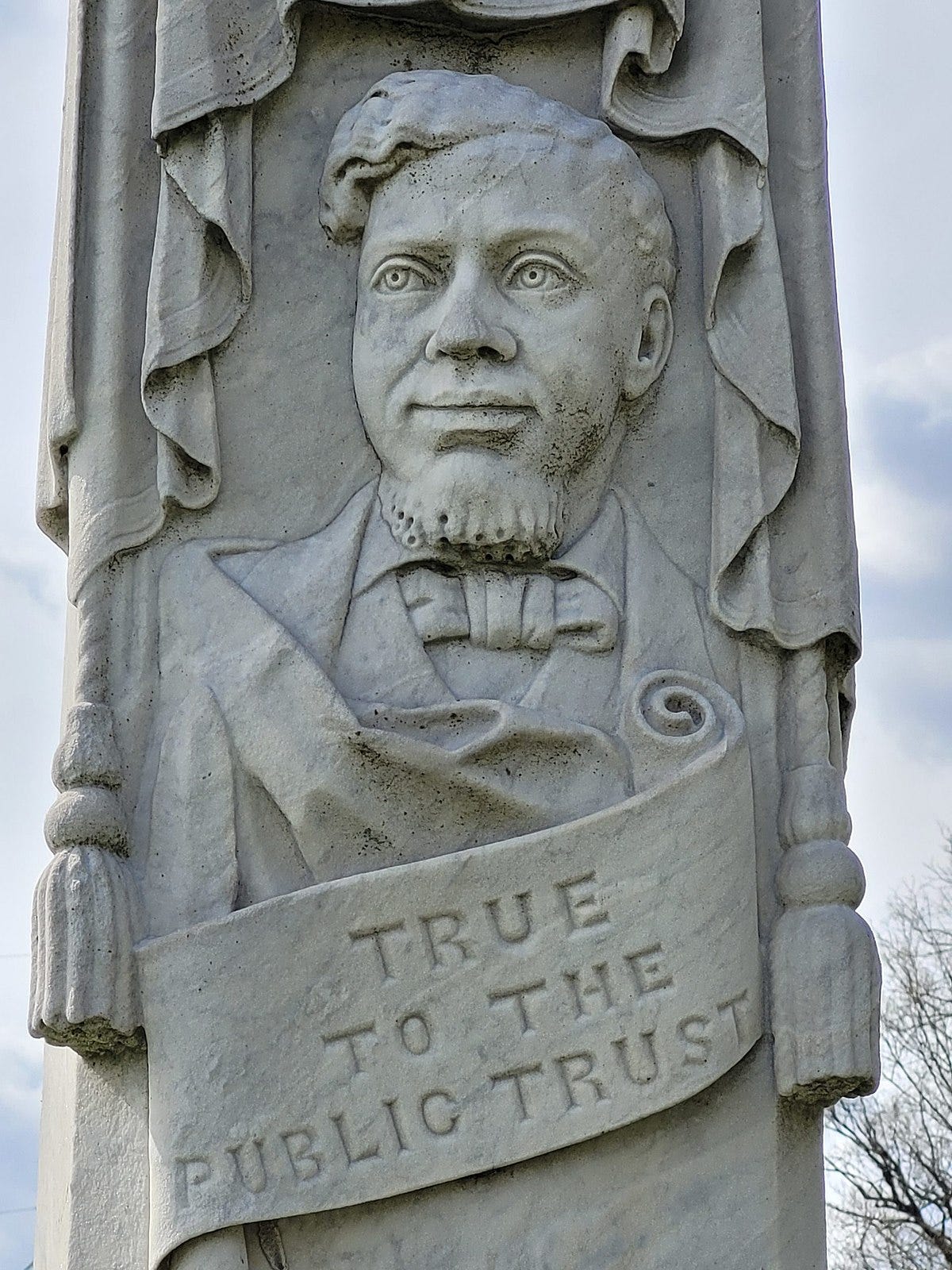

According to the Mississippi Encyclopedia’s article on Lynch, his Philadelphia speech was considered so effective that he was “invited to campaign for the reelection of Pres. Ulysses S. Grant in Indiana and Illinois.” But his failing health and political reverses after the convention—he was denied the Republican nomination for a Congressional seat that he might well have won, in part because of allegations of heavy drinking and rape charges, of which he was acquitted—intervened, tragically. Just six months later, days after Christmas, he died of Bright’s disease, a kidney ailment—ironically, days after the sudden death of Reform Republican nominee Horace Greeley, the man he had urged black voters not to vote for.

Jackson cemetery monument to Mississippi leader James D. Lynch, who died in December 1872. Public domain photo

Nor would Grey serve as a delegate to another Republican convention. Hobbled by a series of strokes between 1873 and 1880, Grey would retire from public life entirely as an invalid before his untimely death in 1888.

Elliott resigned from Congress in 1874, serving once again in the South Carolina legislature, and was elected as its Speaker. Chosen twice more as a convention delegate, in 1876 and 1880, he won his 1876 campaign for state attorney general, but was forced to resign less than a year later. Afterward, he left politics and eventually moved to Louisiana, where he practiced law briefly before his death in 1884.

Only James Harris would last the distance, serving in every successive North Carolina delegation until 1888. But his unsuccessful second bid for Congress in 1878—as a reform Republican spoiler, blocking James O’Hara from victory in his first bid for the office—left hard feelings, marking a certain loss of influence within the party as a whole. He went on to serve two more terms as a state legislator, then won several elections as a Raleigh city alderman; around 1890, he left that city for a new career in Washington, D.C., but instead died there in May 1891.

Both Harris and Elliott would serve as delegates to the 1876 convention in Cincinnati, at which it required seven ballots to nominate candidate Rutherford B. Hayes. They were among 31 repeat attendees, out of 50-odd voting delegates. Experience was valued, but a new generation of leaders was also competing.

Except for the South Carolina delegation—on which all but one delegate and two alternates had previously been named to serve in Philadelphia—most of the African American faces in Cincinnati would belong to new state leaders from the South.

Next time: Even as Reconstruction wanes, Cincinnati beckons to black delegates