African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 2: The long shadow cast by the Port Royal experiment

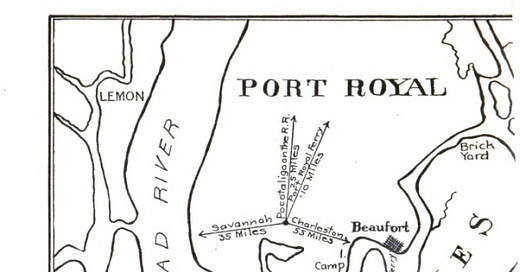

Portion of Sea Islands map, ca. 1906. Drawing from Elizabeth Ware Pearson’s Letters from Port Royal

Much has been written about the so-called Port Royal experiment, which began in 1861 on one of South Carolina’s Sea Islands. Its largest city, Beaufort, “was the first southern city conquered by Union forces after the U.S. Navy victory in Port Royal Sound on November 7, 1861,” according to the South Carolina Encyclopedia, and “became the headquarters of the U.S. Army, Department of the South, and most of the buildings were converted into hospitals for Union army wounded.”

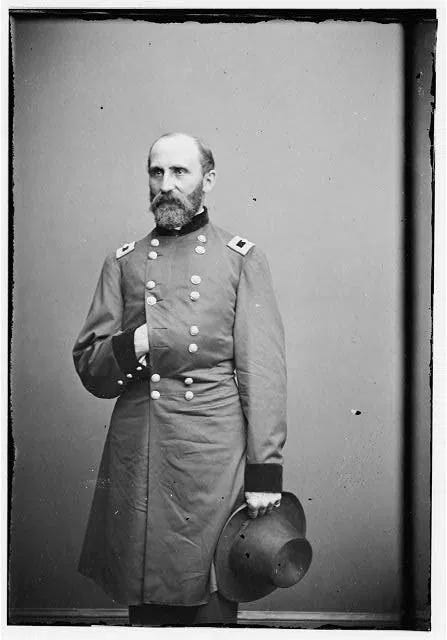

In 1862, Major General Rufus Saxton assumed control of the island as Military Governor of the Department of the South—those portions of coastal South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida under Union control—with headquarters in Beaufort. He quickly emerged as the guiding light of the Port Royal experiment, which “became a proving ground for the education of freedmen and a ‘rehearsal’ for postwar Reconstruction,” according to the Massachusetts Historical Society. Most of the white slaveholding population had fled, abandoning thousands of slaves; reform-minded missionaries and abolitionists soon filled the vacuum.

General Saxton quickly “chafed in his role as a military administrator and devoted much of his time and energy to the recruitment and training of former slaves as soldiers. He personally recruited Captain Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a minister and abolitionist from Massachusetts who was serving as a regular officer in the Union Army, to command the First South Carolina Volunteers.”

A career Army officier and opponent of slavery, Saxton was determined to set a clear and convincing example of leadership for black Sea Islanders, both the soldiers he was helping recruit and the thousands of civilians now scrambling to embrace freedom. As New Year’s Day 1863 drew near, Saxton sent out a special greeting to island residents in December 1862 to gather in the town to hear the official reading of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, when “you will be declared ‘forever free’ … and to indulge such other manifestations of joy as may be called forth by the occasion.

It is your duty to carry this good news to your brethren who are still in slavery. Let all your voices, like merry bells, join loud and clear in the grand chorus of liberty—’We are free,’ ‘We are free’—until listening, you shall hear its echoes coming back from every cabin in the land …

General Saxton’s New Year’s greeting to black residents of Port Royal. Courtesy Massachusetts Historical Society

[See “A Happy New Year’s Greeting to the Colored People in the Department of the South,” December 1862, https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=2443&pid=3 .]

And while the Proclamation that they would hear was Lincoln’s provisional version from September 1862—the actual version arrived in camp weeks later—its meaning was the same as that actually issued on January 1, 1863. As instructed, Colonel Higginson duly organized the great celebration Saxton had envisioned, expecting 5,000 slaves to attend the event. Higginson had 10 oxen roasted for the occasion to be washed down by a “slight collation” of barrels of molasses mixed with water—but no alcohol!—as he later described in his 1869 memoir (Army Life in a Black Regiment).

Higginson’s poetic account of the day’s events follows:

About ten o'clock the people began to collect by land, and also by water,—in steamers sent by General Saxton for the purpose; and from that time all the avenues of approach were thronged. The multitude were chiefly colored women, with gay handkerchiefs on their heads, and a sprinkling of men, with that peculiarly respectable look which these people always have on Sundays and holidays. There were many white visitors also—ladies on horseback and in carriages, superintendents and teachers, officers, and cavalry-men.

Our companies were marched to the neighborhood of the platform, and allowed to sit or stand, as at the Sunday services; the platform was occupied by ladies and dignitaries, and by the band of the Eighth Maine, which kindly volunteered for the occasion; the colored people filled up all the vacant openings in the beautiful grove around, and there was a cordon of mounted visitors beyond. …

The services began at half past eleven o'clock, with prayer by our chaplain, Mr. Fowler, who is always, on such occasions, simple, reverential, and impressive. Then the President's Proclamation was read by Dr. W. H. Brisbane, a thing infinitely appropriate, a South Carolinian addressing South Carolinians; for he was reared among these very islands, and here long since emancipated his own slaves. Then the colors were presented to us by the Rev. Mr. French, a chaplain who brought them from the donors in New York. All this was according to the programme.

“Then followed an incident so simple, so touching, so utterly unexpected and startling, that I can scarcely believe it on recalling, though it gave the keynote to the whole day,” Higginson, an ordained minister, recalled. “The very moment the speaker had ceased, and just as I took and waved the flag, which now for the first time meant anything to these poor people, there suddenly arose, close beside the platform, a strong male voice (but rather cracked and elderly), into which two women's voices instantly blended, singing, as if by an impulse that could no more be repressed than the morning note of the song-sparrow.—

"My Country, 'tis of thee,

Sweet land of liberty,

Of thee I sing!"

The day was a “perfect success,” Higginson thought, with even time for romance, as General Saxton was observed wrapping his sash—a symbol of his rank—around the waist of Matilda Thompson, the “belle of Port Royal,” who had come from Philadelphia to teach in a school for freedmen. (They were married in Beaufort three months later.)

The aggressive recruitment of blacks for the First South Carolina Volunteers then officially commenced. According to his biographical sketch, Saxton took unprecedented initiative “by insisting on treating them with respect and insisting they be enlisted on an equal basis with whites … [he] became trusted by blacks reluctant to fight for a government that discriminated against them.

To help combat the prejudice he found among whites in the army, he gave the black recruits their first opportunity to prove themselves as combat troops by sending a company to operate from aboard a steamer and raid along the coast of Georgia and Florida from November 3rd to the 10th. Lifted by their success and by the public support it brought, he was able to shape the 1st South Carolina Colored Volunteers into the first full-strength officially mandated black regiment in the Federal army.

[See biographical sketch, “Rufus Saxton,” at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/5885503/rufus-saxton .]

But he remained concerned with black civilians as well, trying to reduce the hardships of contrabands by assigning to them parcels of land on Sea Islands estates abandoned by Confederate plantation owners. “The former slaves, supplied by the government with seed and tools, were to grow enough food for their own support and were encouraged by him to market surpluses as a means of becoming independent. In exchange for the opportunity, each farmer was obliged to raise an allotment of cotton for use by the Federal government.”

Dress parade of the South Carolina First Volunteers, Beaufort, undated. Courtesy Library of Congress

General Rufus Saxton (1824-1908), military governor of Port Royal. Courtesy Library of Congress

A page back in time ... is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work,

consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

* * * * * * * * *

General Saxton would remain at his post until the war’s end, in 1865. As noted in my last entry, he chose to join the 16-member provisional delegation Beaufort organizers sent to the Baltimore convention which renominated Lincoln in June 1864—although that delegation took part only as observers. In late 1864, the men of Saxton’s 33rd USCT regiment “served in the operations against Charleston, South Carolina, serving on James Island, Folly Island and Morris Island and all along the South Carolina coast. After Charleston was wrested from the hands of the Confederacy in February 1865, the 33rd served as part of the city's Union garrison.” [See Baxter Fite’s history of the USCT 33rd regiment, at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/264082853/henry-williams .]

After the War ended, General Saxton became the state’s assistant commissioner of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, better known simply as the Freedmen’s Bureau, recently created by Congress. He remained there until his dismissal by President Andrew Johnson in January 1866—perhaps for being too strong an advocate of freedmen’s advancement—and moved on elsewhere in his long Army career, which continued until 1888.

But the impressive personal example he set at Port Royal—“idolized” by his soldiers, according to Higginson—did not disappear. Among the men commanded by General Saxton during his term at Port Royal, at least four went on to follow his inspirational leadership as elected public servants during Reconstruction: black soldiers Prince Rivers and Henry Hayne, whose lives I covered in my previous post, who went on to serve in the South Carolina legislature under the new constitution adopted in 1868, and two white officers—both under his command—stayed behind in South Carolina after the War.

According to Higginson’s memoir, published in 1869, “The officers and men are scattered far and wide. One of our captains was a member of the South Carolina Constitutional Convention, and is now State Treasurer [Niles G. Parker] ; three of our sergeants were in that Convention, including Sergeant Prince Rivers [along with Henry Hayne; and probably Louden Langley]; and he and Sergeant Henry Hayne are still members of the State Legislature. Both in that State and Florida the former members of the regiment are generally prospering, so far as I can hear. The increased self-respect of army life fitted them to do the duties of civil life.”

Rivers remained in South Carolina until his death in 1887, pursuing a distinguished public career until the end of Reconstruction, when he stepped back into obscurity as a house painter. Hayne, who became South Carolina’s first black elected Secretary of State, left the state after 1877, and is believed have died in Illinois in 1898.

Sgt. Maj. Louden Langley, another rare freeborn black, from Vermont, transferred into the 33rd USCT regiment in 1864, after first enlisting in the black 54th Massachusetts regiment in 1863. He represented Beaufort County alongside Robert Smalls at the 1868 South Carolina Constitutional Convention in Charleston; there he argued for a free, equal, and compulsory education for the people of his adopted state. Langley (ca. 1839-1883) served as School Commissioner of Beaufort County before becoming a lighthouse keeper on St. Helena Island; he is buried in Beaufort. His older brother Lewis (1823-1865), who remained in the 54th Massachusetts, is also buried in Beaufort; he died of typhoid fever on nearby Hilton Head in 1865. [See his biographical sketch at https://www.nps.gov/people/louden-langley.htm ; see also “Louden Langley, A soldier without limitations,” 2015, at https://www.islandpacket.com/news/local/community/beaufort-news/bg-military/article33649461.html .]

Gravestone of Sgt. Louden Langley, delegate to constitutional convention. Courtesy National Park Service

Little is known about the postwar career of Sgt. Henry “Harry” Williams, one of those chosen in May 1864 as an alternate delegate to the Baltimore convention, except that he eventually migrated to New Jersey, where he died in Camden County in 1917. Described on his November 1862 enlistment papers as a “butler,” he was quickly promoted, becoming a trusted leader of bands of soldiers sent out to rescue slaves from nearby plantations in South Carolina. Born enslaved in Georgia in 1841, he may have returned to Georgia after his discharge and worked as a turpentine field hand before emigrating. [See Baxter Fite’s biographical sketch, located at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/264082853/henry-williams .]

A few details are known about the actual service of Quartermaster’s Sgt. Edward Colvin (1840-1911), another alternate delegate selected for Baltimore at Beaufort in 1864. According to U.S. Army pension files, he was born in Georgia in 1840, enlisted in November 1863 and mustered out in January 1866; thereafter, he moved back to Savannah, before moving north to Wilmington, Delaware, and then to Washington, D.C., where he died in 1911.

His lengthy pension file—containing at least one letter apparently written by Colvin himself—indicates that before his discharge, Colvin was kicked in the head by a mule, causing later epileptic fits and a lifelong disability. A lengthy investigation conducted by Army officials in the 1880s drew testimony from many 33rd USCT comrades, along with an affidavit from Col. T. W. Higginson. His invalid’s pension claim, initally rejected for lack of evidence, was reopened in the 1890s, and his invalid’s pension finally granted by 1897. [See “Approved Pension File for Quartermaster Edward Colvin,” https://catalog.archives.gov/id/311178666?objectPage=42 .]

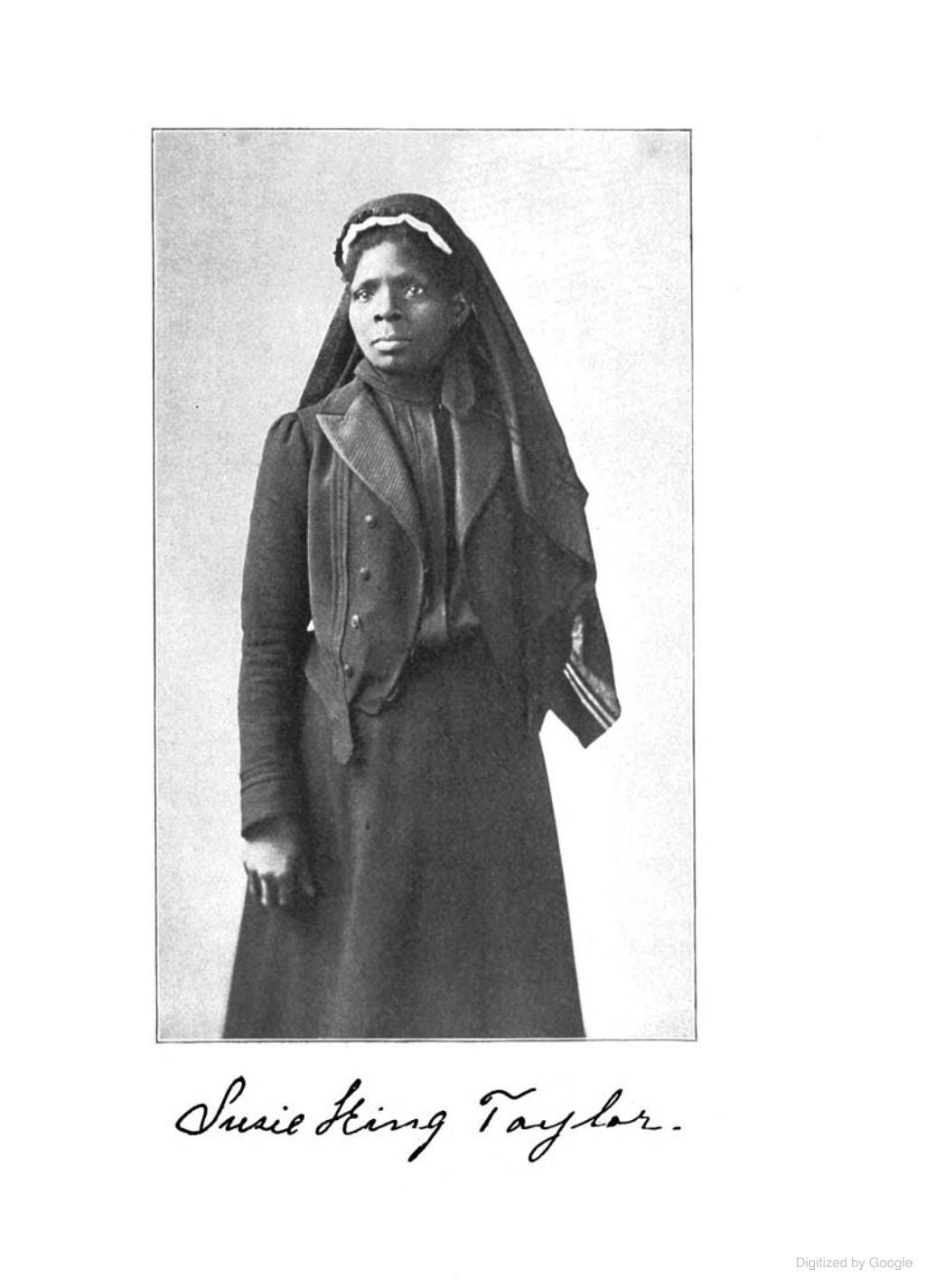

His name is also listed in Susie King Taylor’s 1902 fascinating memoir, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp. During her year with the regiment, she recalled being befriended by the wife of the Quartermaster, Lt. George B. Chamberlin (1837-1915)—Colvin’s immediate superior—through whom she may have come to know Colvin. He was likely a friend of her then husband, Sgt. Edward King, of Company E of the 33rd USCT. A laundress by profession, she was literate—unusual enough for a Georgia-born slave—and recalls teaching men in Company E how to read and write in her spare time.

Susie King Taylor, author of Reminiscences of My Life in Camp (1902). Photo from her book

Niles G. Parker, elected treasurer of South Carolina in 1868. Photo courtesy Findagrave.com

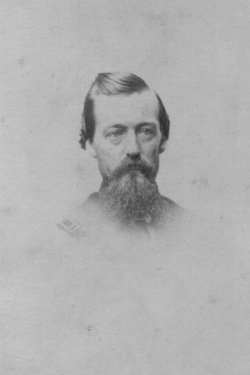

Among those white officers under Saxton’s command in 1863 and 1864 was Captain Niles Gardner Parker (1827-1894), a Massachusetts native who “decided to stay on in Charleston and he must have sent for his family at this time. In 1866 or 1867, Captain Parker was for a short time the senior officer of Castle Pinckney, which was, for a time, used as a jail or prison for local troublemakers,” according to one biographical sketch. “In 1868, with a great desire to help with the reconstruction in whatever way he could, Niles G. Parker decided to run for State Treasurer on the Republican ticket and was elected South Carolina State Treasurer.” [See USCT historian Baxter Fite’s sketch at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/86607783/niles-g_-parker .]

Parker served one term in office, remaining in Columbia as a businessman with real estate interests, including a building known as “Parker’s Block,” in which residential rooms were rented out to state legislators, and later seized by Democratic officials. But his stormy tenure as State Treasurer opened him up to later charges of corruption involving the alleged misappropriation of official coupons related to the state’s “sinking fund.” Arrested and detained for trial in 1877 during the Democratic administration of Governor Wade Hampton, he was never convicted; he died in Massachusetts in 1894.

[See A. A. Taylor, “Corruption Exposed to Justify Intimination,” Journal of Negro History, Vol. 9, No. 4 (Oct., 1924), pp. 517-545; https://doi.org/10.2307/2713550 ; also, F. A. Porcher, “The last chapter in the history of Reconstruction in South Carolina—administration of D. H. Chamberlain,” Southern Historical Society Papers, https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0269%3Achapter%3D48 .]

Another white official who remained in South Carolina after the War—perhaps equally inspired by General Rufus Saxton, his brother-in-law—was James G. Thompson (1836-1901), the spare-time editor of the Beaufort Free South, who had been detailed to Beaufort by the U.S. Treasury Department in July 1862, and who later joined the Army briefly. His younger sister, Matilda, came the same year as a missionary teacher in the new schools for black schoolchildren on Port Royal Island, and then married General Saxton in the spring of 1863.

Captain James G. Thompson, shown in 1864. Photo courtesy Findagrave.com

According to Thompson’s biographical sketch, “In 1864 federal troops were withdrawn from Port Royal and Beaufort and [Thompson] raised a company from civilian government workers. His brother-in-law, Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton, made him a captain, and from Nov. 1864 until Jan. 1865, he and his company were constantly on duty, having furnished their own horses and served without pay.”

As a civilian resident of Pennsylvania, he was entitled to vote in the 1864 election—but only by returning home, which he does not appear to have done; his commission as a Union captain apparently came too late to make him eligible to vote absentee from the field.

But he remained politically active, nonetheless. At war’s end, “he took an active part in the reconstruction of South Carolina,” reportedly the “only northerner and ex-Union man” to attend the state’s later Constitutional Convention, which granted black men the right to vote—though apparently as a journalist, not an official delegate.

In 1868, he established Beaufort Republican and the Port Royal Commercial [newspapers]. In 1870 he was appointed Commissioner of the United States Courts in South Carolina, a position he held for ten years. He was admitted to the bar as an Attorney. … He was editor of the [Union] Herald, the only Republican newspaper published south of the Potomac river.

He also attended a series of Republican national conventions—perhaps as an alternate delegate, more likely as a journalistic observer—ending in 1876. Thompson finally left South Carolina in 1878, later serving as a post office official in Washington, D.C.; he died in his native Pennsylvania in 1901. [See https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/21738762/james-gordon-thompson .]

Next time: Some African American soldiers vote in the field in the 1864 election